The Shapes Arise: Realism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement

Andrea Korda “The Streets as Art Galleries”: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012) Citation: Andrea Korda, “‘The Streets as Art Galleries’: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring12/korda-on-the-streets-as-art-galleries-hubert- herkomer-william-powell-frith-and-the-artistic-advertisement. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Korda: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012) “The Streets as Art Galleries”: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement by Andrea Korda By the second half of the nineteenth century, advertising posters that plastered the streets of London were denounced as one of the evils of modern life. In the article “The Horrors of Street Advertisements,” one writer lamented that “no one can avoid it.… It defaces the streets, and in time must debase the natural sense of colour, and destroy the natural pleasure in design.” For this observer, advertising was “grandiose in its ugliness,” and the advertiser’s only concern was with “bigness, bigness, bigness,” “crudity of colour” and “offensiveness of attitude.”[1] Another commentator added to this criticism with more specific complaints, describing the deficiencies in color, drawing, composition, and the subjects of advertisements in turn. Using adjectives such as garish, hideous, reckless, execrable and horrible, he concluded that advertisers did not aim to appeal to the intellect, but only aimed to attract the public’s attention. -

16 Exhibition on Screen

Exhibition on Screen - The Impressionists – And the Man Who Made Them 2015, Run Time 97 minutes An eagerly anticipated exhibition travelling from the Musee d'Orsay Paris to the National Gallery London and on to the Philadelphia Museum of Art is the focus of the most comprehensive film ever made about the Impressionists. The exhibition brings together Impressionist art accumulated by Paul Durand-Ruel, the 19th century Parisian art collector. Degas, Manet, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, and Sisley, are among the artists that he helped to establish through his galleries in London, New York and Paris. The exhibition, bringing together Durand-Ruel's treasures, is the focus of the film, which also interweaves the story of Impressionism and a look at highlights from Impressionist collections in several prominent American galleries. Paintings: Rosa Bonheur: Ploughing in Nevers, 1849 Constant Troyon: Oxen Ploughing, Morning Effect, 1855 Théodore Rousseau: An Avenue in the Forest of L’Isle-Adam, 1849 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: The Gleaners, 1857 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: The Angelus, c. 1857-1859 (Barbizon School) Charles-François Daubigny: The Grape Harvest in Burgundy, 1863 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: Spring, 1868-1873 (Barbizon School) Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot: Ruins of the Château of Pierrefonds, c. 1830-1835 Théodore Rousseau: View of Mont Blanc, Seen from La Faucille, c. 1863-1867 Eugène Delecroix: Interior of a Dominican Convent in Madrid, 1831 Édouard Manet: Olympia, 1863 Pierre Auguste Renoir: The Swing, 1876 16 Alfred Sisley: Gateway to Argenteuil, 1872 Édouard Manet: Luncheon on the Grass, 1863 Edgar Degas: Ballet Rehearsal on Stage, 1874 Pierre Auguste Renoir: Ball at the Moulin de la Galette, 1876 Pierre Auguste Renoir: Portrait of Mademoiselle Legrand, 1875 Alexandre Cabanel: The Birth of Venus, 1863 Édouard Manet: The Fife Player, 1866 Édouard Manet: The Tragic Actor (Rouvière as Hamlet), 1866 Henri Fantin-Latour: A Studio in the Batingnolles, 1870 Claude Monet: The Thames below Westminster, c. -

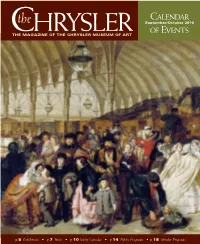

Calendar of Events

Calendar the September/October 2010 hrysler of events CTHE MAGAZINE OF THE CHRYSLER MUSEUM OF ART p 5 Exhibitions • p 7 News • p 10 Daily Calendar • p 14 Public Programs • p 18 Member Programs G ENERAL INFORMATION COVER Contact Us The Museum Shop Group and School Tours William Powell Frith Open during Museum hours (English, 1819–1909) Chrysler Museum of Art (757) 333-6269 The Railway 245 W. Olney Road (757) 333-6297 www.chrysler.org/programs.asp Station (detail), 1862 Norfolk, VA 23510 Oil on canvas Phone: (757) 664-6200 Cuisine & Company Board of Trustees Courtesy of Royal Fax: (757) 664-6201 at The Chrysler Café 2010–2011 Holloway Collection, E-mail: [email protected] Wednesdays, 11 a.m.–8 p.m. Shirley C. Baldwin University of London Website: www.chrysler.org Thursdays–Saturdays, 11 a.m.–3 p.m. Carolyn K. Barry Sundays, 12–3 p.m. Robert M. Boyd Museum Hours (757) 333-6291 Nancy W. Branch Wednesday, 10 a.m.–9 p.m. Macon F. Brock, Jr., Chairman Thursday–Saturday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Historic Houses Robert W. Carter Sunday, 12–5 p.m. Free Admission Andrew S. Fine The Museum galleries are closed each The Moses Myers House Elizabeth Fraim Monday and Tuesday, as well as on 323 E. Freemason St. (at Bank St.), Norfolk David R. Goode, Vice Chairman major holidays. The Norfolk History Museum at the Cyrus W. Grandy V Marc Jacobson Admission Willoughby-Baylor House 601 E. Freemason Street, Norfolk Maurice A. Jones General admission to the Chrysler Museum Linda H. -

A Field Awaits Its Next Audience

Victorian Paintings from London's Royal Academy: ” J* ml . ■ A Field Awaits Its Next Audience Peter Trippi Editor, Fine Art Connoisseur Figure l William Powell Frith (1819-1909), The Private View of the Royal Academy, 1881. 1883, oil on canvas, 40% x 77 inches (102.9 x 195.6 cm). Private collection -15- ALTHOUGH AMERICANS' REGARD FOR 19TH CENTURY European art has never been higher, we remain relatively unfamiliar with the artworks produced for the academies that once dominated the scene. This is due partly to the 20th century ascent of modernist artists, who naturally dis couraged study of the academic system they had rejected, and partly to American museums deciding to warehouse and sell off their academic holdings after 1930. In these more even-handed times, when seemingly everything is collectible, our understanding of the 19th century art world will never be complete if we do not look carefully at the academic works prized most highly by it. Our collective awareness is growing slowly, primarily through closer study of Paris, which, as capital of the late 19th century art world, was ruled not by Manet or Monet, but by J.-L. Gerome and A.-W. Bouguereau, among other Figure 2 Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) Study for And the Sea Gave Up the Dead Which Were in It: Male Figure. 1877-82, black and white chalk on brown paper, 12% x 8% inches (32.1 x 22 cm) Leighton House Museum, London Figure 3 Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) Elisha Raising the Son of the Shunamite Woman 1881, oil on canvas, 33 x 54 inches (83.8 x 137 cm) Leighton House Museum, London -16- J ! , /' i - / . -

Wilde's World

Wilde’s World Anne Anderson Aesthetic London Wilde appeared on London’s cultural scene at a propitious moment; with the opening of the Grosvenor Gallery in May 1877 the Aesthetes gained the public platform they had been denied. Sir Coutts Lindsay and his wife Blanche, who were behind this audacious enterprise, invited Edward Burne-Jones, George Frederick Watts, and James McNeill Whistler to participate in the first exhibition; all had suffered rejections from the Royal Academy.1 The public were suddenly confronted with the avant-garde, Pre-Raphaelitism, Symbolism, and even French Naturalism. Wilde immediately recognized his opportunity, as few would understand “Art for Art’s sake,” that paintings no longer had to be didactic or moralizing. Rather, the function of art was to appeal to the senses, to focus on color, form, and composition. Moreover, the aesthetes blurred the distinction between the fine and decorative arts, transforming wallpapers and textiles into objets d’art. The goal was to surround oneself with beauty, to create a House Beautiful. Wilde hitched his star to Aestheticism while an undergraduate at Oxford; his rooms were noted for their beauty, the panelled walls thickly hung with old engravings and contemporary prints by Burne-Jones and filled with exquisite objects: Blue and White Oriental porcelain, Tanagra statuettes brought back from Greece, and Persian rugs. He was also aware of the controversy surrounding Aestheticism; debated in the Oxford and Cambridge Undergraduate in April and May 1877, the magazine at first praised the movement as a civilizing influence. It quickly recanted, as it sought “‘implicit sanction’” for “‘Pagan worship of bodily form and beauty’” and renounced morals in the name of liberty (Ellmann 85, emphasis in original). -

Charles Lang Freer and His Gallery of Art : Turn-Of-The-Century Politics and Aesthetics on the National Mall

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2007 Charles Lang Freer and his gallery of art : turn-of-the-century politics and aesthetics on the National Mall. Patricia L. Guardiola University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Guardiola, Patricia L., "Charles Lang Freer and his gallery of art : turn-of-the-century politics and aesthetics on the National Mall." (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 543. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/543 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHARLES LANG FREER AND HIS GALLERY OF ART: TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY POLITICS AND AESTHETICS ON THE NATIONAL MALL By Patricia L. Guardiola B.A., Bellarmine University, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements F or the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Fine Arts University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky August 2007 CHARLES LANG FREER AND HIS GALLERY OF ART: TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY POLITICS AND AESTHETICS ON THE NATIONAL MALL By Patricia L. Guardiola B.A., Bellarmine University, 2004 A Thesis Approved on June 8, 2007 By the following Thesis Committee: Thesis Director ii DEDICATION In memory of my grandfathers, Mr. -

Iconic Images: the Stories They Tell

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 2011 Volume I: Writing with Words and Images Iconic Images: The Stories They Tell Curriculum Unit 11.01.06 by Kristin M. Wetmore Introduction An important dilemma for me as an art history teacher is how to make the evidence that survives from the past an interesting subject of discussion and learning for my classroom. For the art historian, the evidence is the artwork and the documents that support it. My solution is to have students compare different approaches to a specific historical period because they will have the chance to read primary sources about each of the three images selected, discuss them, and then determine whether and how they reveal, criticize or correctly report the events that they depict. Students should be able to identify if the artist accurately represents an historical event and, if it is not accurately represented, what message the artist is trying to convey. Artists and historians interpret historical events. I would like my students to understand that this interpretation is a construction. Primary documents provide us with just one window to view history. Artwork is another window, but the students must be able to judge on their own the factual content of the work and the artist's intent. It is imperative that students understand this. Barber says in History beyond the Text that there is danger in confusing history as an actual narrative and "construction of the historians (or artist's) craft." 1 The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines iconic as "an emblem or a symbol." 2 The three images I have chosen to study are considered iconic images from the different time periods they represent. -

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). -

Whistler's 'Peacock Room' Reinterpreted at the V&A

Visual Arts Whistler’s ‘Peacock Room’ reinterpreted at the V&A The installation by Darren Waterston is, like the original, an ‘overbearing exercise in decadence’ ‘Filthy Lucre’, Darren Waterston’s installation, a recreation of Whistler’s ‘Peacock Room’ © Amber Gray Lucy Watson JANUARY 24 2020 Opening this weekend at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum is a new installation: a reinterpreted, restaged 19th-century room. It is, according to its 21st-century creator Darren Waterston, “grotesque”. “Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room” was one of the few forays into three dimensions by James Abbott McNeill Whistler, the American painter best-known for his austere 1871 portrait of his mother. Completed in 1877, the original was a dining room in a Kensington house, covered in vivid jade and gold chinoiserie murals and commissioned for the home of Frederick Richards Leyland, a shipping magnate, to display his collection of Asian ceramics. The room was completed by Whistler while his patron was abroad. On his return, Leyland hated it. Two years later, Whistler fell into debt, including to Leyland, and was forced to auction his home and studio in Chelsea. There for inspection by the creditors was a painting called “The Gold Scab: Eruption in Frilthy Lucre (The Creditor)” — in which Leyland was caricatured dressed as a peacock, surrounded by bags of money and sitting atop Whistler’s house. As a final withering statement, the painting was placed in the gilt frame that had been designed for the Peacock Room. https://www.ft.com/content/a76066b0-3d80-11ea-a01a-bae547046735 1/28/2020 Whistler’s ‘Peacock Room’ reinterpreted at the V&A | Financial Times 'The Gold Scab: Eruption in Frilthy Lucre (The Creditor)' by James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1879) The original interior is in Washington DC’s Freer Gallery of Art, but the V&A has brought a version to Kensington, moments from the Prince’s Gate apartment for which it was designed. -

A Pivotal Point: James Mcneill Whistler's Harmony in Blue and Silver

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 2019 A Pivotal Point: James McNeill Whistler’s Harmony in Blue and Silver: Trouville and the Formation of his Aesthetic Eugenie B. Fortier CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/454 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] A Pivotal Point: James McNeill Whistler’s Harmony in Blue and Silver: Trouville and the Formation of his Aesthetic by Eugenie Fortier Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2019 Thesis Sponsor: May 22, 2019 Tara Zanardi Date Signature May 22, 2019 Maria Antonella Pelizzari Date Signature of Second Reader i Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………….……………………………………….………………ii List of Illustrations………………………………………………………………………………..iii Introduction…………… …………………………………………………………………...…….1 Chapter 1: Whistler’s Search for Artistic Identity………………….………….………………...15 Whistler Beginnings: Etching as Experimentation………………..….………………….17 “The Wind Blows from the East:” Eastern Influence on Whistler’s Early Paintings……26 From Icon to Index: Whistler’s Japonisme………………………………...…………….32 A Visible Search for Artistic Identity: Whistler’s Self-Portrait……………...…………..37 Chapter 2: Harmony -

After Whistler: the Artist & His Influence on American Painting

LINDA MERRILL Emory University Art History Department Atlanta, Georgia 30322 404.727-0514 [email protected] Education University of London (University College), England PhD, History of Art, 1985 Dissertation: “The Diffusion of Aesthetic Taste: Whistler and the Popularization of Aestheticism, 1875– 1881.” Advisor: William H. T. Vaughan. Marshall Scholarship, 1981–84, awarded by the Marshall Plan Commemoration Commission of Great Britain for postgraduate study. Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts AB, English, 1981. Summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, with Highest Honors in English, 1981. Employment Emory University, Atlanta Senior Lecturer and Director of Undergraduate Studies in Art History, Fall 2016—present Lecturer and Director of Undergraduate Studies in Art History, Fall 2013-16 Freer Gallery of Art/Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Guest curator, with Dr. Robyn Asleson, of The Lost Symphony: Whistler and the Perfection of Art, January 16— May 30, 2016. Global Fine Art Award for Best Thematic Impressionist/Modern Exhibition 2016. National Endowment for the Humanities, Office of the Chairman, Washington, D.C. Humanities Administrator, November 2006–April 2007 (temporary appointment). High Museum of Art, Atlanta Margaret and Terry Stent Curator of American Art, 1998–2000 Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Curator of American Art, 1997–98; Associate Curator of American Art, 1990–97; Assistant Curator of American Art, 1985–90. Hood College, Frederick, Maryland, Department of Art History Visiting Assistant Professor in Art History, Spring 1991, 1985–86. Publications Books After Whistler: The Artist & His Influence on American Painting. New Haven: Yale University Press and the High Museum of Art, 2003. -

The Barbizon School of Painters Were Part of an Art Movement Towards Realism in Art, Which Arose in the Context of the Dominant Romantic Movement of the Time

Barbizon School The Barbizon school of painters were part of an art movement towards Realism in art, which arose in the context of the dominant Romantic Movement of the time. The Barbizon school was active roughly from 1830 until 1870. It takes its name from the village of Barbizon, France, near the Forest of Fontainebleau, where many of the artists gathered. Some of the most prominent features of this school are its tonal qualities, colour, loose brushwork, and softness of form. In 1824 the Salon de Paris exhibited works of John Constable. His rural scenes influenced some of the younger artists of the time, moving them to abandon formalism and to draw inspiration directly from nature. Natural scenes became the subjects of their paintings rather than mere backdrops to dramatic events. During the Revolutions of 1848 artists gathered at Barbizon to follow Constable's ideas, making nature the subject of their paintings. The French landscape became a major theme of the Barbizon painters. The leaders of the Barbizon school were Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, and Charles-François Daubigny. Rousseau, Thunderstorms mood in the level of Montmartre 1845-48 Rousseau, Avenue of Chestnut Treees Rousseau, Avenue of Chestnut Treees 1837 watercolour Théodore Rousseau (1812 – 1867) was born in Paris, France in a bourgeois family. Although at first his father regretted his decision to persue a carreer as an artist he became reconciled to his son forsaking business, and throughout the artist's career (for he survived his son) was a sympathizer with him in all his conflicts with the Paris Salon authorities.