Wilde's World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement

Andrea Korda “The Streets as Art Galleries”: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012) Citation: Andrea Korda, “‘The Streets as Art Galleries’: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring12/korda-on-the-streets-as-art-galleries-hubert- herkomer-william-powell-frith-and-the-artistic-advertisement. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Korda: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012) “The Streets as Art Galleries”: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement by Andrea Korda By the second half of the nineteenth century, advertising posters that plastered the streets of London were denounced as one of the evils of modern life. In the article “The Horrors of Street Advertisements,” one writer lamented that “no one can avoid it.… It defaces the streets, and in time must debase the natural sense of colour, and destroy the natural pleasure in design.” For this observer, advertising was “grandiose in its ugliness,” and the advertiser’s only concern was with “bigness, bigness, bigness,” “crudity of colour” and “offensiveness of attitude.”[1] Another commentator added to this criticism with more specific complaints, describing the deficiencies in color, drawing, composition, and the subjects of advertisements in turn. Using adjectives such as garish, hideous, reckless, execrable and horrible, he concluded that advertisers did not aim to appeal to the intellect, but only aimed to attract the public’s attention. -

Calendar of Events

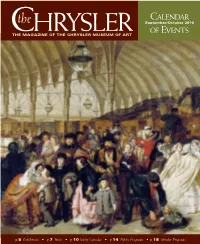

Calendar the September/October 2010 hrysler of events CTHE MAGAZINE OF THE CHRYSLER MUSEUM OF ART p 5 Exhibitions • p 7 News • p 10 Daily Calendar • p 14 Public Programs • p 18 Member Programs G ENERAL INFORMATION COVER Contact Us The Museum Shop Group and School Tours William Powell Frith Open during Museum hours (English, 1819–1909) Chrysler Museum of Art (757) 333-6269 The Railway 245 W. Olney Road (757) 333-6297 www.chrysler.org/programs.asp Station (detail), 1862 Norfolk, VA 23510 Oil on canvas Phone: (757) 664-6200 Cuisine & Company Board of Trustees Courtesy of Royal Fax: (757) 664-6201 at The Chrysler Café 2010–2011 Holloway Collection, E-mail: [email protected] Wednesdays, 11 a.m.–8 p.m. Shirley C. Baldwin University of London Website: www.chrysler.org Thursdays–Saturdays, 11 a.m.–3 p.m. Carolyn K. Barry Sundays, 12–3 p.m. Robert M. Boyd Museum Hours (757) 333-6291 Nancy W. Branch Wednesday, 10 a.m.–9 p.m. Macon F. Brock, Jr., Chairman Thursday–Saturday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Historic Houses Robert W. Carter Sunday, 12–5 p.m. Free Admission Andrew S. Fine The Museum galleries are closed each The Moses Myers House Elizabeth Fraim Monday and Tuesday, as well as on 323 E. Freemason St. (at Bank St.), Norfolk David R. Goode, Vice Chairman major holidays. The Norfolk History Museum at the Cyrus W. Grandy V Marc Jacobson Admission Willoughby-Baylor House 601 E. Freemason Street, Norfolk Maurice A. Jones General admission to the Chrysler Museum Linda H. -

A Field Awaits Its Next Audience

Victorian Paintings from London's Royal Academy: ” J* ml . ■ A Field Awaits Its Next Audience Peter Trippi Editor, Fine Art Connoisseur Figure l William Powell Frith (1819-1909), The Private View of the Royal Academy, 1881. 1883, oil on canvas, 40% x 77 inches (102.9 x 195.6 cm). Private collection -15- ALTHOUGH AMERICANS' REGARD FOR 19TH CENTURY European art has never been higher, we remain relatively unfamiliar with the artworks produced for the academies that once dominated the scene. This is due partly to the 20th century ascent of modernist artists, who naturally dis couraged study of the academic system they had rejected, and partly to American museums deciding to warehouse and sell off their academic holdings after 1930. In these more even-handed times, when seemingly everything is collectible, our understanding of the 19th century art world will never be complete if we do not look carefully at the academic works prized most highly by it. Our collective awareness is growing slowly, primarily through closer study of Paris, which, as capital of the late 19th century art world, was ruled not by Manet or Monet, but by J.-L. Gerome and A.-W. Bouguereau, among other Figure 2 Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) Study for And the Sea Gave Up the Dead Which Were in It: Male Figure. 1877-82, black and white chalk on brown paper, 12% x 8% inches (32.1 x 22 cm) Leighton House Museum, London Figure 3 Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) Elisha Raising the Son of the Shunamite Woman 1881, oil on canvas, 33 x 54 inches (83.8 x 137 cm) Leighton House Museum, London -16- J ! , /' i - / . -

Victorian Paintings Anne-Florence Gillard-Estrada

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archive Ouverte en Sciences de l'Information et de la Communication Fantasied images of women: representations of myths of the golden apples in “classic” Victorian paintings Anne-Florence Gillard-Estrada To cite this version: Anne-Florence Gillard-Estrada. Fantasied images of women: representations of myths of the golden apples in “classic” Victorian paintings. Polysèmes, Société des amis d’inter-textes (SAIT), 2016, L’or et l’art, 10.4000/polysemes.860. hal-02092857 HAL Id: hal-02092857 https://hal-normandie-univ.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02092857 Submitted on 8 Apr 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Fantasied images of women: representations of myths of the golden apples in “classic” Victorian Paintings This article proposes to examine the treatment of Greek myths of the golden apples in paintings by late-Victorian artists then categorized in contemporary reception as “classical” or “classic.” These terms recur in many reviews published in periodicals.1 The artists concerned were trained in the academic and neoclassical Continental tradition, and they turned to Antiquity for their forms and subjects. -

Iconic Images: the Stories They Tell

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 2011 Volume I: Writing with Words and Images Iconic Images: The Stories They Tell Curriculum Unit 11.01.06 by Kristin M. Wetmore Introduction An important dilemma for me as an art history teacher is how to make the evidence that survives from the past an interesting subject of discussion and learning for my classroom. For the art historian, the evidence is the artwork and the documents that support it. My solution is to have students compare different approaches to a specific historical period because they will have the chance to read primary sources about each of the three images selected, discuss them, and then determine whether and how they reveal, criticize or correctly report the events that they depict. Students should be able to identify if the artist accurately represents an historical event and, if it is not accurately represented, what message the artist is trying to convey. Artists and historians interpret historical events. I would like my students to understand that this interpretation is a construction. Primary documents provide us with just one window to view history. Artwork is another window, but the students must be able to judge on their own the factual content of the work and the artist's intent. It is imperative that students understand this. Barber says in History beyond the Text that there is danger in confusing history as an actual narrative and "construction of the historians (or artist's) craft." 1 The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines iconic as "an emblem or a symbol." 2 The three images I have chosen to study are considered iconic images from the different time periods they represent. -

The People's Institute, the National Board of Censorship and the Problem of Leisure in Urban America

In Defense of the Moving Pictures: The People's Institute, The National Board of Censorship and the Problem of Leisure in Urban America Nancy J, Rosenbloom Located in the midst of a vibrant and ethnically diverse working-class neighborhood on New York's Lower East Side, the People's Institute had by 1909 earned a reputation as a maverick among community organizations.1 Under the leadership of Charles Sprague Smith, its founder and managing director, the Institute supported a number of political and cultural activities for the immigrant and working classes. Among the projects to which Sprague Smith committed the People's Institute was the National Board of Censorship of Motion Pictures. From its creation in June 1909 two things were unusual about the National Board of Censorship. First, its name to the contrary, the Board opposed growing pressures for legalized censorship; instead it sought the voluntary cooperation of the industry in a plan aimed at improving the quality and quantity of pictures produced. Second, the Board's close affiliation with the People's Institute from 1909 to 1915 was informed by a set of assumptions about the social usefulness of moving pictures that set it apart from many of the ideas dominating American reform. In positioning itself to defend the moving picture industry, the New York- based Board developed a national profile and entered into a close alliance with the newly formed Motion Picture Patents Company. What resulted was a partnership between businessmen and reformers that sought to offset middle-class criticism of the medium. The officers of the Motion Picture Patents Company also hoped 0026-3079/92/3302-O41$1.50/0 41 to increase middle-class patronage of the moving pictures through their support of the National Board. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting Template

THE IDEAL OF THE REAL: MID-VICTORIAN REPRESENTATIONS OF THE ARTIST AND THE INVENTION OF REALISM By DANIEL SCHULTZ BROWN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2012 1 © 2012 Daniel Schultz Brown 2 To my advisor, Pamela Gilbert: for tireless patience, steadfast support and gentle guidance 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS page LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... 6 ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... 7 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 11 History of Realism ................................................................................................... 14 Overview of Critical Literature ................................................................................. 21 Chapter Overview ................................................................................................... 34 2 “LESS EASILY DEFINED THAN APPREHENDED”: MID-VICTORAIN THEORIES OF REALISM ....................................................................................... 41 John Ruskin ............................................................................................................ 45 George Henry Lewes ............................................................................................. -

Three Centuries of British Art

Three Centuries of British Art Three Centuries of British Art Friday 30th September – Saturday 22nd October 2011 Shepherd & Derom Galleries in association with Nicholas Bagshawe Fine Art, London Campbell Wilson, Aberdeenshire, Scotland Moore-Gwyn Fine Art, London EIGHTEENTH CENTURY cat. 1 Francis Wheatley, ra (1747–1801) Going Milking Oil on Canvas; 14 × 12 inches Francis Wheatley was born in Covent Garden in London in 1747. His artistic training took place first at Shipley’s drawing classes and then at the newly formed Royal Academy Schools. He was a gifted draughtsman and won a number of prizes as a young man from the Society of Artists. His early work consists mainly of portraits and conversation pieces. These recall the work of Johann Zoffany (1733–1810) and Benjamin Wilson (1721–1788), under whom he is thought to have studied. John Hamilton Mortimer (1740–1779), his friend and occasional collaborator, was also a considerable influence on him in his early years. Despite some success at the outset, Wheatley’s fortunes began to suffer due to an excessively extravagant life-style and in 1779 he travelled to Ireland, mainly to escape his creditors. There he survived by painting portraits and local scenes for patrons and by 1784 was back in England. On his return his painting changed direction and he began to produce a type of painting best described as sentimental genre, whose guiding influence was the work of the French artist Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725–1805). Wheatley’s new work in this style began to attract considerable notice and in the 1790’s he embarked upon his famous series of The Cries of London – scenes of street vendors selling their wares in the capital. -

John Leech His Life and Work Vol Ii William Powell Frith, R.A

JOHN LEECH HIS LIFE AND WORK VOL II WILLIAM POWELL FRITH, R.A. CHAPTER I. "PUNCH." In the year 1841 I exhibited a picture at the Suffolk Street Gallery, and I recollect accidentally overhearing fragments of a conversation between a certain Joe Allen and a brother member of the Society of British Artists in Suffolk Street. Allen's picture happened to hang near mine, and we were both "touching up" our productions. Joe Allen was the funny man of the society, and, though he startled me a little, he did not surprise me by a loud and really good imitation of the peculiar squeak of Punch. "Look out, my boy," he said to his friend, "for the first number. We" (I suppose he was a member of the first staff) "shall take the town by storm. There is no mistake about it. We have so-and-so"—naming some well-known men—"for writers; Hine, Kenny Meadows, young Leech, and a lot more first-rate illustrators," etc. Whether Allen's friend took his advice and bought the first number of Punch, which appeared in the following July, I know not; but I bought a copy, and remember my disappointment at finding Leech conspicuous by his absence from the pages. In the hope of finding him in the second issue, I went to the shop where I had bought the first. The shopman met my request for the second number of Punch, as well as I can recollect, in the following words: "What paper, sir? Oh, Punch! Yes, I took a few of the first; but it's no go. -

The Looking-Glass World: Mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite Painting 1850-1915

THE LOOKING-GLASS WORLD Mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite Painting, 1850-1915 TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I Claire Elizabeth Yearwood Ph.D. University of York History of Art October 2014 Abstract This dissertation examines the role of mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite painting as a significant motif that ultimately contributes to the on-going discussion surrounding the problematic PRB label. With varying stylistic objectives that often appear contradictory, as well as the disbandment of the original Brotherhood a few short years after it formed, defining ‘Pre-Raphaelite’ as a style remains an intriguing puzzle. In spite of recurring frequently in the works of the Pre-Raphaelites, particularly in those by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt, the mirror has not been thoroughly investigated before. Instead, the use of the mirror is typically mentioned briefly within the larger structure of analysis and most often referred to as a quotation of Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434) or as a symbol of vanity without giving further thought to the connotations of the mirror as a distinguishing mark of the movement. I argue for an analysis of the mirror both within the context of iconographic exchange between the original leaders and their later associates and followers, and also that of nineteenth- century glass production. The Pre-Raphaelite use of the mirror establishes a complex iconography that effectively remytholgises an industrial object, conflates contradictory elements of past and present, spiritual and physical, and contributes to a specific artistic dialogue between the disparate strands of the movement that anchors the problematic PRB label within a context of iconographic exchange. -

DICKENS FINAL with ILLUS.Ppp

The Dickens Calendar 2012 The Dickens Calendar 2012 Celebrating the bicentenary of Dickens’s birth. £6.00 each or £10.00 for 2 (plus postage) Contact Jarndyce to order your copy: Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 7631 4220 35 _____________________________________________________________ Jarndyce Antiquarian Booksellers 46, Great Russell Street Telephone: 020 - 7631 4220 (opp. British Museum) Fax: 020 - 7631 1882 Bloomsbury, Email: [email protected] London WC1B 3PA V.A.T. No. GB 524 0890 57 _____________________________________________________________ CATALOGUE CXCV WINTER 2011-12 THE DICKENS CATALOGUE Catalogue: Joshua Clayton Production: Carol Murphy All items are London-published and in at least good condition, unless otherwise stated. Prices are nett. Items on this catalogue marked with a dagger (†) incur VAT (current rate 20%) A charge for postage and insurance will be added to the invoice total. We accept payment by VISA or MASTERCARD. If payment is made by US cheque, please add $25.00 towards the costs of conversion. Email address for this catalogue is [email protected]. JARNDYCE CATALOGUES CURRENTLY AVAILABLE, price £5.00 each include: Social Science Parts I & II: Politics & Philosophy and Economics & Social History. Women III: Women Writers J-Q; The Museum: Books for Presents; Books & Pamphlets of the 17th & 18th Centuries; 'Mischievous Literature': Bloods & Penny Dreadfuls; The Social History of London: including Poverty & Public Health; The Jarndyce Gazette: Newspapers, 1660 - 1954; Street Literature: I Broadsides, Slipsongs & Ballads; II Chapbooks & Tracts; George MacDonald. JARNDYCE CATALOGUES IN PREPARATION include: The Museum: Jarndyce Miscellany; The Library of a Dickensian; Women Writers R-Z; Street Literature: III Songsters, Lottery Puffs, Street Literature Works of Reference. -

Transactions Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History Antiquarian Society

Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society LXXXIII 2009 Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society FOUNDED 20th NOVEMBER, 1862 THIRD SERIES VOLUME LXXXIII Editors: JAMES WILLIAMS, R. McEWEN and FRANCIS TOOLIS ISSN 0141-1292 2009 DUMFRIES Published by the Council of the Society Office-Bearers 2008-2009 and Fellows of the Society President Morag Williams, MA Vice Presidents Mr J McKinnell, Dr A Terry, Mr J L Williams and Mrs J Brann Fellows of the Society Mr J Banks, BSc; Mr A D Anderson, BSc; Mr J Chinnock; Mr J H D Gair, MA, Dr J B Wilson, MD; Mr K H Dobie; Mrs E Toolis, BA and Dr D F Devereux, PhD. Mr J Williams, Mr L J Masters and Mr R H McEwen — appointed under Rule 10 Hon. Secretary John L Williams, Merkland, Kirkmahoe, Dumfries DG1 1SY Hon. Membership Secretary Miss H Barrington, 30 Noblehill Avenue, Dumfries DG1 3HR Hon. Treasurer Mr L Murray, 24 Corberry Park, Dumfries DG2 7NG Hon. Librarian Mr R Coleman, 2 Loreburn Park, Dumfries DG1 1LS Assisted by Mr J Williams, 43 New Abbey Road, Dumfries DG2 7LZ Joint Hon. Editors Mr J Williams and Mr R H McEwen, 5 Arthur’s Place, Lockerbie DG11 2EB Assisted by Dr F Toolis, 25 Dalbeattie Road, Dumfries DG2 7PF Hon. Syllabus Convener Mrs E Toolis, 25 Dalbeattie Road, Dumfries DG2 7PF Hon. Curators Mrs J Turner and Ms S Ratchford Hon. Outings Organisers Mr J Copland and Mr Alastair Gair Ordinary Members Mr R Copland, Dr J Foster, Mrs P G Williams, Mr D Rose, Mrs C Inglehart, Mr A Pallister, Mr R McCubbin, Dr F Toolis, Mr I Wismach and Mrs J Turner CONTENTS Ostracods from the Wet Moat at Caerlaverock Castle by Mervin Kontrovitz and Huw I Griffiths .......................................................