UCC Library and UCC Researchers Have Made This Item Openly Available

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement

Andrea Korda “The Streets as Art Galleries”: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012) Citation: Andrea Korda, “‘The Streets as Art Galleries’: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring12/korda-on-the-streets-as-art-galleries-hubert- herkomer-william-powell-frith-and-the-artistic-advertisement. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Korda: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012) “The Streets as Art Galleries”: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement by Andrea Korda By the second half of the nineteenth century, advertising posters that plastered the streets of London were denounced as one of the evils of modern life. In the article “The Horrors of Street Advertisements,” one writer lamented that “no one can avoid it.… It defaces the streets, and in time must debase the natural sense of colour, and destroy the natural pleasure in design.” For this observer, advertising was “grandiose in its ugliness,” and the advertiser’s only concern was with “bigness, bigness, bigness,” “crudity of colour” and “offensiveness of attitude.”[1] Another commentator added to this criticism with more specific complaints, describing the deficiencies in color, drawing, composition, and the subjects of advertisements in turn. Using adjectives such as garish, hideous, reckless, execrable and horrible, he concluded that advertisers did not aim to appeal to the intellect, but only aimed to attract the public’s attention. -

Calendar of Events

Calendar the September/October 2010 hrysler of events CTHE MAGAZINE OF THE CHRYSLER MUSEUM OF ART p 5 Exhibitions • p 7 News • p 10 Daily Calendar • p 14 Public Programs • p 18 Member Programs G ENERAL INFORMATION COVER Contact Us The Museum Shop Group and School Tours William Powell Frith Open during Museum hours (English, 1819–1909) Chrysler Museum of Art (757) 333-6269 The Railway 245 W. Olney Road (757) 333-6297 www.chrysler.org/programs.asp Station (detail), 1862 Norfolk, VA 23510 Oil on canvas Phone: (757) 664-6200 Cuisine & Company Board of Trustees Courtesy of Royal Fax: (757) 664-6201 at The Chrysler Café 2010–2011 Holloway Collection, E-mail: [email protected] Wednesdays, 11 a.m.–8 p.m. Shirley C. Baldwin University of London Website: www.chrysler.org Thursdays–Saturdays, 11 a.m.–3 p.m. Carolyn K. Barry Sundays, 12–3 p.m. Robert M. Boyd Museum Hours (757) 333-6291 Nancy W. Branch Wednesday, 10 a.m.–9 p.m. Macon F. Brock, Jr., Chairman Thursday–Saturday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Historic Houses Robert W. Carter Sunday, 12–5 p.m. Free Admission Andrew S. Fine The Museum galleries are closed each The Moses Myers House Elizabeth Fraim Monday and Tuesday, as well as on 323 E. Freemason St. (at Bank St.), Norfolk David R. Goode, Vice Chairman major holidays. The Norfolk History Museum at the Cyrus W. Grandy V Marc Jacobson Admission Willoughby-Baylor House 601 E. Freemason Street, Norfolk Maurice A. Jones General admission to the Chrysler Museum Linda H. -

A Field Awaits Its Next Audience

Victorian Paintings from London's Royal Academy: ” J* ml . ■ A Field Awaits Its Next Audience Peter Trippi Editor, Fine Art Connoisseur Figure l William Powell Frith (1819-1909), The Private View of the Royal Academy, 1881. 1883, oil on canvas, 40% x 77 inches (102.9 x 195.6 cm). Private collection -15- ALTHOUGH AMERICANS' REGARD FOR 19TH CENTURY European art has never been higher, we remain relatively unfamiliar with the artworks produced for the academies that once dominated the scene. This is due partly to the 20th century ascent of modernist artists, who naturally dis couraged study of the academic system they had rejected, and partly to American museums deciding to warehouse and sell off their academic holdings after 1930. In these more even-handed times, when seemingly everything is collectible, our understanding of the 19th century art world will never be complete if we do not look carefully at the academic works prized most highly by it. Our collective awareness is growing slowly, primarily through closer study of Paris, which, as capital of the late 19th century art world, was ruled not by Manet or Monet, but by J.-L. Gerome and A.-W. Bouguereau, among other Figure 2 Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) Study for And the Sea Gave Up the Dead Which Were in It: Male Figure. 1877-82, black and white chalk on brown paper, 12% x 8% inches (32.1 x 22 cm) Leighton House Museum, London Figure 3 Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) Elisha Raising the Son of the Shunamite Woman 1881, oil on canvas, 33 x 54 inches (83.8 x 137 cm) Leighton House Museum, London -16- J ! , /' i - / . -

Fine Arts Paris Wednesday 7 November - Sunday 11 November 2018 Carrousel Du Louvre / Paris

Fine Arts Paris WednesdAy 7 november - sundAy 11 november 2018 CArrousel du louvre / PAris press kit n o s s e t n o m e d y u g n a t www.finearts-paris.com t i d e r c Fine Arts Paris From 7 to 11 november 2018 CArrousel du louvre / PAris Fine Arts Paris From 7 to 11 november 2018 CArrousel du louvre / PAris Hours Tuesday, 6 November 2018 / Preview 3 pm - 10 pm Wednesday, 7 November 2018 / 2 pm - 8 pm Thursday 8 November 2018 / noon - 10 pm Friday 9 November 2018 / noon - 8 pm Saturday 10 November 2018 / noon - 8 pm Sunday 11 November 2018 / noon - 7 pm admission: €15 (catalogue included, as long as stocks last) Half price: students under the age of 26 FINE ARTS PARIS Press oPening Main office tuesdAy 6 november 68, Bd malesherbes, 75008 paris 2 Pm Hélène mouradian: + 33 (0)1 45 22 08 77 Social media claire Dubois and manon Girard: Art Content + 33 (0)1 45 22 61 06 Denise Hermanns contact@finearts-paris.com & Jeanette Gerritsma +31 30 2819 654 Press contacts [email protected] Agence Art & Communication 29, rue de ponthieu, 75008 paris sylvie robaglia: + 33 (0)6 72 59 57 34 [email protected] samantha Bergognon: + 33 (0)6 25 04 62 29 [email protected] charlotte corre: + 33 (0)6 36 66 06 77 [email protected] n o s s e t n o m e d y u g n a t t i d e r c Fine Arts Paris From 7 to 11 november 2018 CArrousel du louvre / PAris "We have chosen the Carrousel du Louvre as the venue for FINE ARTS PARIS because we want the fair to be a major event for both the fine arts and for Paris, and an important date on every collector’s calendar. -

Sir Joseph Noel Paton: the Reconciliation of Oberon and Titania

Art Appreciation Lecture Series 2015 Meet the Masters: Highlights from the Scottish National Gallery “The Reconciliation of Oberon and Titania” Sir Joseph Noel Paton Craig Judd 2/3 September 2015 Born off Wooer’s alley in Dunfermline Fife to damask workers to knighthood and works acquired by Queen Victoria the career of Joseph Noel Paton (1821-1901) is literally one of rags to riches. Studying briefly in London 1843, he became close friends with John Everett Millais and was invited to be a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood an offer he rejected. Nevertheless much of his work is infused with the same spirit of self conscious moralising conservatism. “The Reconciliation of Oberon and Titania”(1847) and its companion piece “The Quarrel of Oberon and Titania” (1846) easily captured critical and public imagination, won prizes and provided the inital entré for the artist into the Royal Scottish Academy.Paton was an avid antiquary and folklorist swept up in the tartan led fantasies of the Prince Albert Queen Victoria/ Balmoral Scottish Revival consequently many of his works are skilled programmatic illustrations derived from literature. Also a skilled watercolourist Paton became the Queens Limner for Scotland in 1865. “The Reconciliation of Oberon and Titania”(1847) represents the high water mark of a billabong of Victorian taste. A surprisingly wild and sensual mass of swirling flesh it depicts the happy conclusion of William Shakespeare’s “A Midsummers Nights Dream”.This lecture will introduce the genre of Fairy Painting as well as discuss the often overlooked career and broader cultural contexts of Sir Joseph Noel Paton. -

La Poesia in Europa : Novalis, Dagli Inni Alla Notte, Primo Inno Alla Notte

Anno Scolastico 2019-2020 Programma classe 5 sezione I Prof.ssa Rosaria Maria Tozzi Testi in adozione: G. Baldi, S. Giusso, M. Razetti, G. Zaccaria, I classici nostri contemporanei voll.4,5.1,5.2 , Paravia ● L’ETA’ DEL ROMANTICISMO 1816 - 1860 Origine del termine Romanticismo Le principali radici storiche e culturali del Romanticismo Aspetti generali del Romanticismo europeo: il ruolo dell’intellettuale e dell’artista e la mercificazione dell’arte – il rifiuto della ragione e l’irrazionale – inquietudine e fuga dalla realtà presente. Autori e opere del Romanticismo europeo Peculiarità del Romanticismo italiano: Romanticismo italiano e Romanticismo europeo – Romanticismo italiano e Illuminismo - fisionomia e ruolo sociale degli intellettuali – pubblico e produzione letteraria. La concezione dell’arte e della letteratura nel romanticismo europeo : la poetica classicistica e la poetica romantica La poesia in Europa : Novalis, dagli Inni alla notte, Primo inno alla notte Il romanzo realista di ambiente contemporaneo: Honoré de Balzac: lettura integrale del romanzo Papa Goriot Il Romanticismo in Italia : la polemica coi classicisti – la poetica dei romantici italiani Madame de Stael: Sulla maniera e l’utilità delle traduzioni (passi antologizzati sul manuale) La poesia in Italia: i principali filoni della poesia romantica in Italia Il romanzo in Italia: l’affermazione del genere, la fioritura del romanzo storico, il romanzo sociale e psicologico . Alessandro Manzoni: la biografia – la concezione della storia e della letteratura nelle opere prima della conversione e dopo la conversione . Il problema del romanzo: l’ideale manzoniano di società; l’intreccio del romanzo e la formazione di Renzo e Lucia ; la concezione manzoniana della Provvidenza; il problema della lingua ; le principali differenze tra le diverse redazioni del romanzo. -

Fanny Eaton: the 'Other' Pre-Raphaelite Model' Pre ~ R2.Phadite -Related Books , and Hope That These Will Be of Interest to You and Inspire You to Further Reading

which will continue. I know that many members are avid readers of Fanny Eaton: The 'Other' Pre-Raphaelite Model' Pre ~ R2.phadite -related books , and hope that these will be of interest to you and inspire you to further reading. If you are interested in writing reviews Robeno C. Ferrad for us, please get in touch with me or Ka.tja. This issue has bee n delayed due to personal circumstances,so I must offer speciaJ thanks to Sophie Clarke for her help in editing and p roo f~read in g izzie Siddall. Jane Morris. Annie Mine r. Maria Zamhaco. to en'able me to catch up! Anyone who has studied the Pre-Raphaelite paintings of Dante. G abriel RosS(:tti, William Holman Hunt, and Edward Serena Trrrwhridge I) - Burne~Jonc.s kno\VS well the names of these women. They were the stunners who populated their paintings, exuding sensual imagery and Advertisement personalized symbolism that generated for them and their collectors an introspeClive idea l of Victorian fem ininity. But these stunners also appear in art history today thanks to fe mi nism and gender snldies. Sensational . Avoncroft Museu m of Historic Buildings and scholnrly explorations of the lives and representations of these Avoncroft .. near Bromsgrove is an award-winning ~' women-written mostly by women, from Lucinda H awksley to G riselda Museum muS(: um that spans 700 years of life in the Pollock- have become more common in Pre·Raphaelite studies.2 Indeed, West Midlands. It is England's first open ~ air one arguably now needs to know more about the. -

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). -

GERMAN LITERARY FAIRY TALES, 1795-1848 by CLAUDIA MAREIKE

ROMANTICISM, ORIENTALISM, AND NATIONAL IDENTITY: GERMAN LITERARY FAIRY TALES, 1795-1848 By CLAUDIA MAREIKE KATRIN SCHWABE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2012 1 © 2012 Claudia Mareike Katrin Schwabe 2 To my beloved parents Dr. Roman and Cornelia Schwabe 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisory committee chair, Dr. Barbara Mennel, who supported this project with great encouragement, enthusiasm, guidance, solidarity, and outstanding academic scholarship. I am particularly grateful for her dedication and tireless efforts in editing my chapters during the various phases of this dissertation. I could not have asked for a better, more genuine mentor. I also want to express my gratitude to the other committee members, Dr. Will Hasty, Dr. Franz Futterknecht, and Dr. John Cech, for their thoughtful comments and suggestions, invaluable feedback, and for offering me new perspectives. Furthermore, I would like to acknowledge the abundant support and inspiration of my friends and colleagues Anna Rutz, Tim Fangmeyer, and Dr. Keith Bullivant. My heartfelt gratitude goes to my family, particularly my parents, Dr. Roman and Cornelia Schwabe, as well as to my brother Marius and his wife Marina Schwabe. Many thanks also to my dear friends for all their love and their emotional support throughout the years: Silke Noll, Alice Mantey, Lea Hüllen, and Tina Dolge. In addition, Paul and Deborah Watford deserve special mentioning who so graciously and welcomingly invited me into their home and family. Final thanks go to Stephen Geist and his parents who believed in me from the very start. -

Download This PDF File

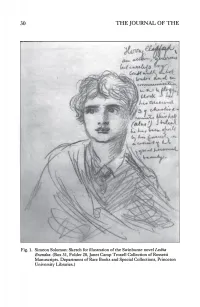

30 THE JOURNAL OF THE Fig. 1. Simeon Solomon: Sketch for illustration of the Swinburne novel Lesbla Brandon. (Box 31, Folder 20, Janet Gamp Troxell Collection of Rossetti Manuscripts. Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Libraries.) RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES 31 SWINBURNE AT PRINCETON BY MARGARET M. SHERRY Dr. Sherry is Reference Librarian and Archivist at Princeton University In the 1860s Swinburne was as engaged in writing fiction as in producing material for his first published volume of poetry, Poems and Ballads. The manuscript of his novel Lesbia Brandon, however, never went into print during his lifetime because Watts-Dunton disapproved of its incestuous subtext.1 The opening pages of the novel, which was published only posthumously by Randolph Hughes in 1952, give a detailed description of two pairs of eyes, those of brother and sister. Their resemblance to one another is so uncanny as to make both seem sexually ambiguous, if not entirely androgynous: "Either smiled with the same lips and looked straight with the same clear eyes."2 The frontispiece to this article, Figure 1, a sketch by the artist Simeon Solomon, gives us some idea of what the idealized beauty of the characters in this novel was to be. The second illustration, Figure 2, shows the younger brother Herbert, recovering from a flogging, sitting with his sister who has turned to look at him from where she sits at the piano. Herbert's teacher Denham, it is explained in the narrative, enjoys flogging his teenage pupil to punish Herbert's sister indirectly for being sexually inaccessible to him — she is already a married woman. -

Press Release Pre-Raphaelites on Paper, Leighton House Museum

PRESS RELEASE Pre-Raphaelites on Paper: Victorian Drawings from the Lanigan Collection An exhibition at Leighton House Museum organised by the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa 12 Feb 2016 – 29 May 2016 Press Preview 11 Feb 2016 Pre-Raphaelites on Paper: Victorian Drawings from the Lanigan Collection will be the first exhibition opening at Leighton House Museum in 2016, presenting an exceptional, privately- assembled collection to the UK public for the first time. Featuring over 100 drawings and sketches by the Pre- Raphaelites and their contemporaries, the exhibition is organised by the National Gallery of Canada (NGC). It expresses the richness and flair of British draftsmanship during the Victorian era displayed in the unique setting of the opulent home and studio of artist and President of the Royal Academy (PRA) Frederic, Lord Leighton. From preparatory sketches to highly finished drawings intended as works of art in themselves, visitors will discover the diverse ways that Victorian artists used drawing to further their artistic practice, creating, as they did so, images of great beauty and accomplishment. Portraits, landscapes, allegories and scenes from religious and literary works are all represented in the exhibition including studies for some of the most well-known paintings of the era such as Edward Burne- Jones’ The Wheel of Fortune (1883), Holman Hunt’s Eve of St Agnes (1848) and Leighton’s Cymon and Iphigenia (1884). With the exception of Leighton’s painting studio, the permanent collection will be cleared from Leighton House and the drawings hung throughout the historic interiors. This outstanding collection, brought together over a 30-year period by Canadian Dr. -

The Looking-Glass World: Mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite Painting 1850-1915

THE LOOKING-GLASS WORLD Mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite Painting, 1850-1915 TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I Claire Elizabeth Yearwood Ph.D. University of York History of Art October 2014 Abstract This dissertation examines the role of mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite painting as a significant motif that ultimately contributes to the on-going discussion surrounding the problematic PRB label. With varying stylistic objectives that often appear contradictory, as well as the disbandment of the original Brotherhood a few short years after it formed, defining ‘Pre-Raphaelite’ as a style remains an intriguing puzzle. In spite of recurring frequently in the works of the Pre-Raphaelites, particularly in those by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt, the mirror has not been thoroughly investigated before. Instead, the use of the mirror is typically mentioned briefly within the larger structure of analysis and most often referred to as a quotation of Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434) or as a symbol of vanity without giving further thought to the connotations of the mirror as a distinguishing mark of the movement. I argue for an analysis of the mirror both within the context of iconographic exchange between the original leaders and their later associates and followers, and also that of nineteenth- century glass production. The Pre-Raphaelite use of the mirror establishes a complex iconography that effectively remytholgises an industrial object, conflates contradictory elements of past and present, spiritual and physical, and contributes to a specific artistic dialogue between the disparate strands of the movement that anchors the problematic PRB label within a context of iconographic exchange.