On Gender and the Division of Artistic and Domestic Labour in Nineteenth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Darwin: a Companion

CHARLES DARWIN: A COMPANION Charles Darwin aged 59. Reproduction of a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron, original 13 x 10 inches, taken at Dumbola Lodge, Freshwater, Isle of Wight in July 1869. The original print is signed and authenticated by Mrs Cameron and also signed by Darwin. It bears Colnaghi's blind embossed registration. [page 3] CHARLES DARWIN A Companion by R. B. FREEMAN Department of Zoology University College London DAWSON [page 4] First published in 1978 © R. B. Freeman 1978 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher: Wm Dawson & Sons Ltd, Cannon House Folkestone, Kent, England Archon Books, The Shoe String Press, Inc 995 Sherman Avenue, Hamden, Connecticut 06514 USA British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Freeman, Richard Broke. Charles Darwin. 1. Darwin, Charles – Dictionaries, indexes, etc. 575′. 0092′4 QH31. D2 ISBN 0–7129–0901–X Archon ISBN 0–208–01739–9 LC 78–40928 Filmset in 11/12 pt Bembo Printed and bound in Great Britain by W & J Mackay Limited, Chatham [page 5] CONTENTS List of Illustrations 6 Introduction 7 Acknowledgements 10 Abbreviations 11 Text 17–309 [page 6] LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Charles Darwin aged 59 Frontispiece From a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron Skeleton Pedigree of Charles Robert Darwin 66 Pedigree to show Charles Robert Darwin's Relationship to his Wife Emma 67 Wedgwood Pedigree of Robert Darwin's Children and Grandchildren 68 Arms and Crest of Robert Waring Darwin 69 Research Notes on Insectivorous Plants 1860 90 Charles Darwin's Full Signature 91 [page 7] INTRODUCTION THIS Companion is about Charles Darwin the man: it is not about evolution by natural selection, nor is it about any other of his theoretical or experimental work. -

Julia Margaret Cameron's Photographs As Paintings

University Libraries Lance and Elena Calvert Calvert Undergraduate Research Awards Award for Undergraduate Research 2018 Julia Margaret Cameron's Photographs as Paintings Winnie Wu [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/award Part of the Art Practice Commons, Photography Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Repository Citation Wu, W. (2018). Julia Margaret Cameron's Photographs as Paintings. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/award/34 This Research Paper is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Research Paper in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Research Paper has been accepted for inclusion in Calvert Undergraduate Research Awards by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JULIA MARGARET CAMERON’S PHOTOGRAPHS AS PAINTINGS Winnie Wu ART 475: History of Photography November 30th, 2017 !1 Julia Margaret Cameron did not have a camera until she was forty-eight, given to her by her daughter and son-in-law.1 She did not have mechanical expertise, scientific knowledge, or practical experience in the arts. She was a wife of a philosopher and a mother of seven children.2 Through her husband’s society however, she was in contact with some of the preeminent Victorian thinkers and artists. -

Fanny Eaton: the 'Other' Pre-Raphaelite Model' Pre ~ R2.Phadite -Related Books , and Hope That These Will Be of Interest to You and Inspire You to Further Reading

which will continue. I know that many members are avid readers of Fanny Eaton: The 'Other' Pre-Raphaelite Model' Pre ~ R2.phadite -related books , and hope that these will be of interest to you and inspire you to further reading. If you are interested in writing reviews Robeno C. Ferrad for us, please get in touch with me or Ka.tja. This issue has bee n delayed due to personal circumstances,so I must offer speciaJ thanks to Sophie Clarke for her help in editing and p roo f~read in g izzie Siddall. Jane Morris. Annie Mine r. Maria Zamhaco. to en'able me to catch up! Anyone who has studied the Pre-Raphaelite paintings of Dante. G abriel RosS(:tti, William Holman Hunt, and Edward Serena Trrrwhridge I) - Burne~Jonc.s kno\VS well the names of these women. They were the stunners who populated their paintings, exuding sensual imagery and Advertisement personalized symbolism that generated for them and their collectors an introspeClive idea l of Victorian fem ininity. But these stunners also appear in art history today thanks to fe mi nism and gender snldies. Sensational . Avoncroft Museu m of Historic Buildings and scholnrly explorations of the lives and representations of these Avoncroft .. near Bromsgrove is an award-winning ~' women-written mostly by women, from Lucinda H awksley to G riselda Museum muS(: um that spans 700 years of life in the Pollock- have become more common in Pre·Raphaelite studies.2 Indeed, West Midlands. It is England's first open ~ air one arguably now needs to know more about the. -

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). -

Press Release the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA

^ press release The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) Announces Beta Release of Collator, a New Way to Create Print-On-Demand Art Books More Than 1,000 High-Res Images from LACMA’s Collection Are Available for Special Customized Books Collator is an initiative of The Hyundai Project: Art + Technology at LACMA (Los Angeles, June 7, 2018)—The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) announced today the launch of Collator, an innovative tool to engage with LACMA’s permanent collection. Inspired by the museum’s commitment to showcasing its vast collections to a diverse and geographically dispersed audience, this new digital platform allows users to curate and publish a custom 24-page paperback book featuring their own selections from the museum’s encyclopedic collections. Collator incorporates new web- based customization technologies that allow users to browse more than 1,000 high- resolution images to create the theme, title, and introductory text of their print-on-demand books. And new images are added regularly. Collator is an initiative of The Hyundai Project: Art+Technology at LACMA, a special partnership between Hyundai Motor and LACMA. “Collator explores the exciting possibilities of museum publishing. This project is an idea we’ve been developing for several years and is now ready for testing,” said Michael Govan, LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director. “By incorporating the latest innovations in print-on-demand technology, Collator gives creative control to audiences all over the world to create an art book of their choice, all featuring works from the museum’s encyclopedic collection. It’s been a pleasure to watch LACMA’s curators engage with Collator to create books about exhibitions and areas of the permanent collection. -

Download This PDF File

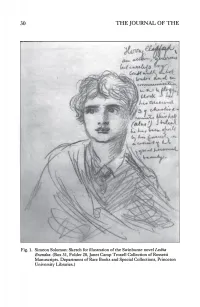

30 THE JOURNAL OF THE Fig. 1. Simeon Solomon: Sketch for illustration of the Swinburne novel Lesbla Brandon. (Box 31, Folder 20, Janet Gamp Troxell Collection of Rossetti Manuscripts. Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Libraries.) RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES 31 SWINBURNE AT PRINCETON BY MARGARET M. SHERRY Dr. Sherry is Reference Librarian and Archivist at Princeton University In the 1860s Swinburne was as engaged in writing fiction as in producing material for his first published volume of poetry, Poems and Ballads. The manuscript of his novel Lesbia Brandon, however, never went into print during his lifetime because Watts-Dunton disapproved of its incestuous subtext.1 The opening pages of the novel, which was published only posthumously by Randolph Hughes in 1952, give a detailed description of two pairs of eyes, those of brother and sister. Their resemblance to one another is so uncanny as to make both seem sexually ambiguous, if not entirely androgynous: "Either smiled with the same lips and looked straight with the same clear eyes."2 The frontispiece to this article, Figure 1, a sketch by the artist Simeon Solomon, gives us some idea of what the idealized beauty of the characters in this novel was to be. The second illustration, Figure 2, shows the younger brother Herbert, recovering from a flogging, sitting with his sister who has turned to look at him from where she sits at the piano. Herbert's teacher Denham, it is explained in the narrative, enjoys flogging his teenage pupil to punish Herbert's sister indirectly for being sexually inaccessible to him — she is already a married woman. -

“He Hath Mingled with the Ungodly”

―HE HATH MINGLED WITH THE UNGODLY‖: THE LIFE OF SIMEON SOLOMON AFTER 1873, WITH A SURVEY OF THE EXTANT WORKS CAROLYN CONROY TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I PH.D. THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART DECEMBER 2009 2 ABSTRACT This thesis focuses on the life and work of the marginalized British Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic homosexual Jewish painter Simeon Solomon (1840-1905) after 1873.This year was fundamental in the artist‘s professional and personal life, because it is the year that he was arrested for attempted sodomy charges in London. The popular view that has been disseminated by the early historiography of Solomon, since before and after his death in 1905, has been to claim that, after this date, the artist led a life that was worthless, both personally and artistically. It has also asserted that this situation was self-inflicted, and that, despite the consistent efforts of his family and friends to return him to the conventions of Victorian middle-class life, he resisted, and that, this resistant was evidence of his ‗deviancy‘. Indeed, for over sixty years, the overall effect of this early historiography has been to defame the character of Solomon and reduce his importance within the Aesthetic movement and the second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism. It has also had the effect of relegating the work that he produced after 1873 to either virtual obscurity or critical censure. In fact, it is only recently that a revival of interest in the artist has gained momentum, although the latter part of his life from 1873 has still remained under- researched and unrecorded. -

How Four Museums Are Taking Dramatic Measures to Admit More

Women's Place in the Art World Case Studies: How Four Museums Are Taking Dramatic Measures to Admit More Women Artists Into the Art Historical Canon We examine how four museums are adopting different strategies to move the needle on the representation of women in art history. Julia Halperin & Charlotte Burns, September 19, 2019 Opening for "Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future." Photo: Paul Rudd © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Our research reveals just how little art by women is being collected and exhibited by museums. But some institutions are beginning to address the problem—and starting to find solutions. Here are four case studies. The Pioneer: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia In recent years, institutions including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Baltimore Museum of Art have made headlines by selling off the work of canonized white men to raise money to diversify their collections. But few are aware that another museum quietly undertook a similar project way back in 2013. Now, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts serves as a case study for how such moves can create permanent and profound change within an institution. PAFA’s decision to auction Edward Hopper’s East Wind Over Weehawken (1934) at Christie’s for $40.5 million was deemed controversial at the time. But the museum and art school has gone on to use the proceeds from that sale to consistently acquire significantly more works by female artists each year than institutions with far larger budgets, such as the Brooklyn Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Dallas Museum of Art. -

Bibliography (Books & Exhibition Catalogues)

513 WEST 20TH STREET NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10011 TEL: 212.645.1701 FAX: 212.645.8316 JACK SHAINMAN GALLERY CARRIE MAE WEEMS SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY (BOOKS & EXHIBITION CATALOGUES) 2021 Selvaratnam, Tanya. Assume Nothing: A Story of Intimate Violence, HarperCollins. 2021. Lewis, Sarah and Garnier, Christine. Carrie Mae Weems, MIT Press, 2021. 2020 Smith, Shawn Michelle. Photographic Returns: Racial Justice and the Time of Photography, Duke University Press. 2020. Childs, Adrienne L. Riffs and Relations: African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition. Rizzoli Electa, 2020. Desmond, Matthew, and Mustafa Emirbayer. Race in America. W. W. Norton, 2020. Perree, Rob. Tell Me Your Story: 100 Years of Storytelling in African American Art. Kusthal Kade, 2020. Publishing, BlackBook. A Woman’s Right to Pleasure. 2020. Smith, Shawn Michelle. Racial Justice and the Time of Photography. Duke University Press, 2020: pp. 2, 4-7, 14, 133-151, 170. Lewis, Sarah Elizabeth. Carrie Mae Weems. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2020. 2019 A Handbook of the Collections. Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, 2019: p. 294-295, illustrated. Carroll, Henry. Be a Super Awesome Photographer. Laurence King Publishing, 2019: p. 53-54, illustrated. Choi, Connie H., Golden, Thelma, Jones, Kellie, Black Refractions: Highlights from The Studio Museum in Harlem. Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 2019: p. 206-207, illustrated. English, Darby, and Charlotte Barat. Among Others. Blackness at MoMA. New York, Museum of Modern Art, 2019: p. 450-453, illustrated. Fellah, Nadiah Rivera. Wendy Red Star: A Scratch on the Earth. Newark Museum Association, 2019: p.17, illustrated. WWW.JACKSHAINMAN.COM [email protected] Carrie Mae Weems: Selected Bibliography Page 2 Get Up, Stand Up Now: Generations of Black Creative Pioneers. -

Photography and the Art of Chance

Photography and the Art of Chance Photography and the Art of Chance Robin Kelsey The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, En gland 2015 Copyright © 2015 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First printing Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Kelsey, Robin, 1961– Photography and the art of chance / Robin Kelsey. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-74400-4 (alk. paper) 1. Photography, Artistic— Philosophy. 2. Chance in art. I. Title. TR642.K445 2015 770— dc23 2014040717 For Cynthia Cone Contents Introduction 1 1 William Henry Fox Talbot and His Picture Machine 12 2 Defi ning Art against the Mechanical, c. 1860 40 3 Julia Margaret Cameron Transfi gures the Glitch 66 4 Th e Fog of Beauty, c. 1890 102 5 Alfred Stieglitz Moves with the City 149 6 Stalking Chance and Making News, c. 1930 180 7 Frederick Sommer Decomposes Our Nature 214 8 Pressing Photography into a Modernist Mold, c. 1970 249 9 John Baldessari Plays the Fool 284 Conclusion 311 Notes 325 Ac know ledg ments 385 Index 389 Photography and the Art of Chance Introduction Can photographs be art? Institutionally, the answer is obviously yes. Our art museums and galleries abound in photography, and our scholarly jour- nals lavish photographs with attention once reserved for work in other media. Although many contemporary artists mix photography with other tech- nical methods, our institutions do not require this. Th e broad affi rmation that photographs can be art, which comes after more than a century of disagreement and doubt, fulfi lls an old dream of uniting creativity and industry, art and automatism, soul and machine. -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

The Looking-Glass World: Mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite Painting 1850-1915

THE LOOKING-GLASS WORLD Mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite Painting, 1850-1915 TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I Claire Elizabeth Yearwood Ph.D. University of York History of Art October 2014 Abstract This dissertation examines the role of mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite painting as a significant motif that ultimately contributes to the on-going discussion surrounding the problematic PRB label. With varying stylistic objectives that often appear contradictory, as well as the disbandment of the original Brotherhood a few short years after it formed, defining ‘Pre-Raphaelite’ as a style remains an intriguing puzzle. In spite of recurring frequently in the works of the Pre-Raphaelites, particularly in those by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt, the mirror has not been thoroughly investigated before. Instead, the use of the mirror is typically mentioned briefly within the larger structure of analysis and most often referred to as a quotation of Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434) or as a symbol of vanity without giving further thought to the connotations of the mirror as a distinguishing mark of the movement. I argue for an analysis of the mirror both within the context of iconographic exchange between the original leaders and their later associates and followers, and also that of nineteenth- century glass production. The Pre-Raphaelite use of the mirror establishes a complex iconography that effectively remytholgises an industrial object, conflates contradictory elements of past and present, spiritual and physical, and contributes to a specific artistic dialogue between the disparate strands of the movement that anchors the problematic PRB label within a context of iconographic exchange.