INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL of DECADENCE STUDIES Issue 1 Spring 2018 Symons and Print Culture: Journalist, Critic, Book Maker Laur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Planning, Irish Modernism, and Dublin

Notes 1 Urbanizing the Revival: Urban Planning, Irish Modernism, and Dublin 1. Arguably Andrew Thacker betrays a similar underlying assumption when he writes of ‘After the Race’: ‘Despite the characterisation of Doyle as a rather shallow enthusiast for motoring, the excitement of the car’s “rapid motion through space” is clearly associated by Joyce with a European modernity to which he, as a writer, aspired’ (Thacker 115). 2. Wirth-Nesher’s understanding of the city, here, is influenced by that of Georg Simmel, whereby the city, while divesting individuals of a sense of communal belonging, also affords them a degree of personal freedom that is impossible in a smaller community (Wirth-Nesher 163). Due to the lack of anonymity in Joyce’s Dublin, an indicator of its pre-urban or non-urban status, this personal freedom is unavailable to Joyce’s characters. ‘There are almost no strangers’ in Dubliners, she writes, with the exceptions of those in ‘An Encounter’ and ‘Araby’ (164). She then enumerates no less than seven strangers in the collection, arguing however that they are ‘invented through the transformation of the familiar into the strange’ (164). 3. Wirth-Nesher’s assumptions about Dublin’s status as a city are not really necessary to the focus of her analysis, which emphasizes the importance Joyce’s early work places on the ‘indeterminacy of the public and private’ and its effects on the social lives of the characters (166). That she chooses to frame this analysis in terms of Dublin’s ‘exacting the price of city life and in turn offering the constraints of a small town’ (173) reveals forcefully the pervasiveness of this type of reading of Joyce’s Dublin. -

Fanny Eaton: the 'Other' Pre-Raphaelite Model' Pre ~ R2.Phadite -Related Books , and Hope That These Will Be of Interest to You and Inspire You to Further Reading

which will continue. I know that many members are avid readers of Fanny Eaton: The 'Other' Pre-Raphaelite Model' Pre ~ R2.phadite -related books , and hope that these will be of interest to you and inspire you to further reading. If you are interested in writing reviews Robeno C. Ferrad for us, please get in touch with me or Ka.tja. This issue has bee n delayed due to personal circumstances,so I must offer speciaJ thanks to Sophie Clarke for her help in editing and p roo f~read in g izzie Siddall. Jane Morris. Annie Mine r. Maria Zamhaco. to en'able me to catch up! Anyone who has studied the Pre-Raphaelite paintings of Dante. G abriel RosS(:tti, William Holman Hunt, and Edward Serena Trrrwhridge I) - Burne~Jonc.s kno\VS well the names of these women. They were the stunners who populated their paintings, exuding sensual imagery and Advertisement personalized symbolism that generated for them and their collectors an introspeClive idea l of Victorian fem ininity. But these stunners also appear in art history today thanks to fe mi nism and gender snldies. Sensational . Avoncroft Museu m of Historic Buildings and scholnrly explorations of the lives and representations of these Avoncroft .. near Bromsgrove is an award-winning ~' women-written mostly by women, from Lucinda H awksley to G riselda Museum muS(: um that spans 700 years of life in the Pollock- have become more common in Pre·Raphaelite studies.2 Indeed, West Midlands. It is England's first open ~ air one arguably now needs to know more about the. -

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). -

James Stephens at Colby College

Colby Quarterly Volume 5 Issue 9 March Article 5 March 1961 James Stephens at Colby College Richard Cary. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, series 5, no.9, March 1961, p.224-253 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Cary.: James Stephens at Colby College 224 Colby Library Quarterly shadow and symbolize death: the ship sailing to the North Pole is the Vehicle of Death, and the captain of the ship is Death himself. Stephens here makes use of traditional motifs. for the purpose of creating a psychological study. These stories are no doubt an attempt at something quite distinct from what actually came to absorb his mind - Irish saga material. It may to my mind be regretted that he did not write more short stories of the same kind as the ones in Etched in Moonlight, the most poignant of which is "Hunger," a starvation story, the tragedy of which is intensified by the lucid, objective style. Unfortunately the scope of this article does not allow a treat ment of the rest of Stephens' work, which I hope to discuss in another essay. I have here dealt with some aspects of the two middle periods of his career, and tried to give significant glimpses of his life in Paris, and his .subsequent years in Dublin. In 1915 he left wartime Paris to return to a revolutionary Dub lin, and in 1925 he left an Ireland suffering from the after effects of the Civil War. -

Download This PDF File

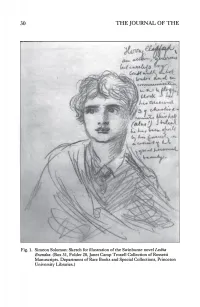

30 THE JOURNAL OF THE Fig. 1. Simeon Solomon: Sketch for illustration of the Swinburne novel Lesbla Brandon. (Box 31, Folder 20, Janet Gamp Troxell Collection of Rossetti Manuscripts. Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Libraries.) RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES 31 SWINBURNE AT PRINCETON BY MARGARET M. SHERRY Dr. Sherry is Reference Librarian and Archivist at Princeton University In the 1860s Swinburne was as engaged in writing fiction as in producing material for his first published volume of poetry, Poems and Ballads. The manuscript of his novel Lesbia Brandon, however, never went into print during his lifetime because Watts-Dunton disapproved of its incestuous subtext.1 The opening pages of the novel, which was published only posthumously by Randolph Hughes in 1952, give a detailed description of two pairs of eyes, those of brother and sister. Their resemblance to one another is so uncanny as to make both seem sexually ambiguous, if not entirely androgynous: "Either smiled with the same lips and looked straight with the same clear eyes."2 The frontispiece to this article, Figure 1, a sketch by the artist Simeon Solomon, gives us some idea of what the idealized beauty of the characters in this novel was to be. The second illustration, Figure 2, shows the younger brother Herbert, recovering from a flogging, sitting with his sister who has turned to look at him from where she sits at the piano. Herbert's teacher Denham, it is explained in the narrative, enjoys flogging his teenage pupil to punish Herbert's sister indirectly for being sexually inaccessible to him — she is already a married woman. -

Francis Thompson and His Relationship to the 1890'S

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1947 Francis Thompson and His Relationship to the 1890's Mary J. Kearney Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Kearney, Mary J., "Francis Thompson and His Relationship to the 1890's" (1947). Master's Theses. 637. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/637 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1947 Mary J. Kearney ii'RJu\fCIS THOi.IPSOH A1fD HIS HELATI01,JSIUP TO Tim 1890'S By Mary J. Kearney A THESIS SUB::iiTTED IN P AHTI.AL FULFILLEENT OF 'riiE HEQUITKii~NTS FOB THE DEGREE OF liil.STEH 01!" ARTS AT LOYOLA UUIV:CflSITY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS June 1947 ------ TABLE OF CO:!TEdT8 CHAPTER PAGE I. Introduction. 1 The heritage of the 1890's--Victorian Liberalis~ Scientific ~laturalism--Intellectual Homanticism Spiritual Inertia--Contrast of the precedi~g to the influence of The Oxford :iJioveo.ent II. Francis Thompson's Iielationsh.in to the "; d <::: • ' 1 ... t ~ _.l:nF ___g_ uleC e \'!rl ers. • •• • • ••••••••• • 17 Characteristics of the period--The decadence of the times--Its perversity, artificiality, egoism and curiosity--Ernest Dawson, the mor bid spirit--Oscar Wilde, the individualist- the Beardsley vision of evil--Thompson's negative revolt--His convictions--The death of the Decadent movement. -

On Gender and the Division of Artistic and Domestic Labour in Nineteenth

The Artist’s Household: On Gender and the Division of Artistic and Domestic Labour in Nineteenth-Century London Lara Perry Contemporary art and art histories are currently having a productive reckoning with the material demands of domestic work and parenting, considered as both a stimulus and constraint to art production. Resonating with the concept of ‘immaterial labour’ that has become prominent in explorations of the structures of contemporary art, feminist artists and critics have exposed the important gendered dimension of the immaterial and socialreproduction labour involved in the career of the contemporary artist. Art projects such as CASCO’s long-term programme (2009-) User’s Manual: The Grand Domestic Revolution and The Mother House project in London (2016) have picked up where Mierle Ukeles Laderman’s performance works of Maintenance Art in the 1960s and 1970s left off, and analysts have similarly refocused their efforts to include considerations of the gendered impact of parenthood on art production. For example, in her book Gender, ArtWork and the Global Imperative: A Materialist Feminist Critique (2013) Angela Dimitrakaki explored the impact of constant travel and around-the-clock schedule on women’s art careers; that this is more of an issue for mothers than for fathers was confirmed by a survey of Swedish artists made by Marita Flisbåck and Sofia Lindstrom (also published in 2013), which offered evidence that the careers of male artists benefit from a greater degree of freedom from the work of the household.1 All of this activity is associated with the investigation of contemporary rather than historical art practices. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The century guild hobby horse and Oscar Wilde: a study of British little magazines, 1884-1897 Tildesley, Matthew Brinton How to cite: Tildesley, Matthew Brinton (2007) The century guild hobby horse and Oscar Wilde: a study of British little magazines, 1884-1897, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/2449/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The Century Guild Hobby Horse and Oscar Wilde: A Study of British Little Magazines, 1884-1897. Matthew Brinton Tildesley. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author or the university to which it was submitted. No quotation from it, or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author or university, and any information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

“He Hath Mingled with the Ungodly”

―HE HATH MINGLED WITH THE UNGODLY‖: THE LIFE OF SIMEON SOLOMON AFTER 1873, WITH A SURVEY OF THE EXTANT WORKS CAROLYN CONROY TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I PH.D. THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART DECEMBER 2009 2 ABSTRACT This thesis focuses on the life and work of the marginalized British Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic homosexual Jewish painter Simeon Solomon (1840-1905) after 1873.This year was fundamental in the artist‘s professional and personal life, because it is the year that he was arrested for attempted sodomy charges in London. The popular view that has been disseminated by the early historiography of Solomon, since before and after his death in 1905, has been to claim that, after this date, the artist led a life that was worthless, both personally and artistically. It has also asserted that this situation was self-inflicted, and that, despite the consistent efforts of his family and friends to return him to the conventions of Victorian middle-class life, he resisted, and that, this resistant was evidence of his ‗deviancy‘. Indeed, for over sixty years, the overall effect of this early historiography has been to defame the character of Solomon and reduce his importance within the Aesthetic movement and the second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism. It has also had the effect of relegating the work that he produced after 1873 to either virtual obscurity or critical censure. In fact, it is only recently that a revival of interest in the artist has gained momentum, although the latter part of his life from 1873 has still remained under- researched and unrecorded. -

A Thesis Presented'to Thef~Culty of the Department of English Indiana

The Renaissance movement in the Irish theatre, 1899-1949 Item Type Thesis Authors Diehl, Margaret Flaherty Download date 06/10/2021 20:08:21 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10484/4764 THE :RENAISSANCE HOVEMENT IN THE IRISH THEATRE 1899... 1949 A Thesis Presented'to TheF~culty of the Department of English Indiana. state Teachers College >" , .. .I 'j' , ;I'" " J' r, " <>.. ~ ,.I :;I~ ~ .~" ",," , '. ' J ' ~ " ") •.;.> / ~ oj.. ., ". j ,. ".,. " l •" J, , ., " .,." , ') I In Partial Fulfillment of the ReqUi:tements for th.eDegree Mast~rofArts in Education by Margaret Flaherty' Diehl June- 1949 i . I .' , is hereby approved as counting toward the completion of the Maste:r's degree in the amount of _L hOUI's' credit. , ~-IU~~~....{.t.}.~~~f...4:~:ti::~~~'~(.{I"''-_' Chairman. Re:prese~ative of Eng /{Sh Depa~ent: b~~~ , ~... PI ACKf.iIUvJLJIDG.fI1:EThTTS The author of this thesis wishes to express her sincere thanks to the members of her committee: (Mrs.) Haze~ T. Pfennig, Ph.D., chairman; (Mrs.) Sara K. Harve,y, Ph.D.; George E. Smock, Ph.D., for their advice and assistance. She appreciates the opportunities fOr research "itlhich have been extended to her, through bo'th Indiana State Teachers College Librar,y and Fairbanks Memoria~ Librar,y. The writer also desires to thank Lennox Robinson and Sean a'Casey fOr their friendly letters" She is espeCially indebted for valuable information afforded her through correspondence with Denis Johnston. Margaret Flaherty Diehl TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I.. BEGINNING OF THE DRAMA IN IRELAND ••••• .. ". 1 Need for this study of the Irish Renaissance .. 1 The English theatre in Ireland • • e' • • " ." 1 Foupding of the Gaiety Theatre . -

Boston College Collection of George Moore 1887-1956 (Bulk 1887-1923) MS.1999.019

Boston College Collection of George Moore 1887-1956 (bulk 1887-1923) MS.1999.019 http://hdl.handle.net/2345/2792 Archives and Manuscripts Department John J. Burns Library Boston College 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill 02467 library.bc.edu/burns/contact URL: http://www.bc.edu/burns Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Biographical note ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Boston College Collection of George Moore MS.1999.019 - Page 2 - Summary Information Creator: Moore, George, 1852-1933 Title: Boston College collection of George Moore ID: MS.1999.019 Date [inclusive]: 1887-1956 Date [bulk]: 1887-1923 Physical Description 1 Linear Feet (4 boxes) Language of the English Material: Abstract: Collection of materials related to Irish author George Moore (1852-1933), including an annotated typescript of Heloise and Abelard, correspondence, -

The Looking-Glass World: Mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite Painting 1850-1915

THE LOOKING-GLASS WORLD Mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite Painting, 1850-1915 TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I Claire Elizabeth Yearwood Ph.D. University of York History of Art October 2014 Abstract This dissertation examines the role of mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite painting as a significant motif that ultimately contributes to the on-going discussion surrounding the problematic PRB label. With varying stylistic objectives that often appear contradictory, as well as the disbandment of the original Brotherhood a few short years after it formed, defining ‘Pre-Raphaelite’ as a style remains an intriguing puzzle. In spite of recurring frequently in the works of the Pre-Raphaelites, particularly in those by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt, the mirror has not been thoroughly investigated before. Instead, the use of the mirror is typically mentioned briefly within the larger structure of analysis and most often referred to as a quotation of Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434) or as a symbol of vanity without giving further thought to the connotations of the mirror as a distinguishing mark of the movement. I argue for an analysis of the mirror both within the context of iconographic exchange between the original leaders and their later associates and followers, and also that of nineteenth- century glass production. The Pre-Raphaelite use of the mirror establishes a complex iconography that effectively remytholgises an industrial object, conflates contradictory elements of past and present, spiritual and physical, and contributes to a specific artistic dialogue between the disparate strands of the movement that anchors the problematic PRB label within a context of iconographic exchange.