Vera Mutafchieva. Albena Hranova

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

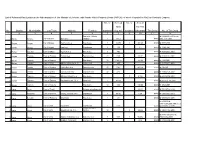

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry Of

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry of Defence, with Private Public Property Deeds (PPPDs), of which Property the MoD is Allowed to Dispose No. of Built-up No. of Area of Area the Plot No. District Municipality City/Town Address Function Buildings (sq. m.) Facilities (decares) Title Deed No. of Title Deed 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Part of the Military № 874/02.05.1997 for the 1 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Slaveykov Hospital 1 545,4 PPPD whole real estate 2 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Kapcheto Area Storehouse 6 623,73 3 29,143 PPPD № 3577/2005 3 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Sarafovo Storehouse 6 439 5,4 PPPD № 2796/2002 4 Burgas Nesebar Town of Obzor Top-Ach Area Storehouse 5 496 PPPD № 4684/26.02.2009 5 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Honyat Area Barracks area 24 9397 49,97 PPPD № 4636/12.12.2008 6 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Storehouse 18 1146,75 74,162 PPPD № 1892/2001 7 Burgas Sozopol Town of Atiya Military station, by Bl. 11 Military club 1 240 PPPD № 3778/22.11.2005 8 Burgas Sredets Town of Sredets Velikin Bair Area Barracks area 17 7912 40,124 PPPD № 3761/05 9 Burgas Sredets Town of Debelt Domuz Dere Area Barracks area 32 5785 PPPD № 4490/24.04.2008 10 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Ahtopol Mitrinkovi Kashli Area Storehouse 1 0,184 PPPD № 4469/09.04.2008 11 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Tsarevo Han Asparuh Str., Bl. -

Contents 107 89 73 59 43 31 23 21 9 5 3

contents Who we are 3 Message by the Chairman 5 Managing Board 9 Supervisory Council 21 Advisory Council 23 Members 31 Commi ees 43 Branches 59 Regions 73 Sectors 89 Events 107 THE VOICE OF BULGARIAN BUSINESS 1 KRIB HAS THE AIM TO BE MOST WIDELY REPRESENTATIVE FOR THE BULGARIAN ECONOMY krib KRIB IS “THE VOICE OF THE BULGARIAN BUSINESS” THAT: produces three quarters of the country’s GDP provides jobs to over 800 000 people unites over 11 000 companies, which are members through individual or collec ve membership, among them the biggest companies in Bulgaria accounts for more than three quarters of the exports of Bulgaria. KRIB HAS A MISSION: to raise the compe veness of the Bulgarian economy and the companies opera ng in Bulgaria to be most eff ec ve in the process of improving the business climate in the country to assist its members in sharing best business prac ces, benefi ng from the EU membership, going regional and global to encourage the corporate social responsibili best prac ces of its members. KRIB IS AN ACTIVE PARTNER IN THE SOCIAL DIALOGUE: has representa ves in the social dialog on na onal, sectoral, regional and European level presents opinions on dra laws in the Bulgarian Parliament is a member of the Na onal Council for Tripar te Coopera on and its commissions its Chairman is Depu -Chairman of the Na onal Council for Tripar te Coopera on. KRIB HAS STRONG REGIONAL AND BRANCH STRUCTURES: operates 113 regional representa ons all over the country unites 65 branch organiza ons in all economic sectors THE VOICE OF BULGARIAN BUSINESS has 10 intersectoral commi ees that coordinate the interests of its members. -

Ghid CDST En.Cdr

EUROPEAN UNION EUROPEAN REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT FUND INVESTING IN YOUR FUTURE! RELIGIOUS TOURISM IN THE CROSS-BORDER REGION ROMANIA-BULGARIA GUIDE BULGARIA 3 4 VIDIN DISTRICT Introduction Vidin district is located in the northwest of Bulgaria, on the border with Serbia (west) and Romania (northeast). The district has an area of 3,032 km2, representing 2.73% of the total area of the country. Vidin has the lowest number of inhabitants / km2 compared to other districts in Bulgaria, the population of the area being 86,927 inhabitants in 2018, according to Eurostat. The district is structured into 10 municipalities on the territory of which 7 cities were constituted - the administrative center is Vidin city located on the Danube river bank. Vidin district has a rich and turbulent history, considering its strategic and geographical importance for the consolidation and definition of the Bulgarian state since the Middle Ages, the territory being a military, transport and commercial center for over 2,000 years. Thus on its territory there are numerous archaeological remains, among the most famous being the Baba Vida Fortress (the only medieval castle in Bulgaria fully preserved, over 2,000 years old), the Castra Martis Fortress (built during the Roman and Byzantine periods, centuries I-VI), the Kaleto Fortress (among the best preserved fortresses in Bulgaria), the ruins of the Roman city Ratiaria (an important gold trading center). The Regional History Museum in Vidin is also an important element of cultural and historical heritage. In the Vidin district numerous pilgrimages can be made, the most famous places of religious worship located in this area being Albotina Monastery in the Danube Plain (dug in the rock), Monastery "The Assumption of the Virgin Mary" (in whose courtyard there is a spring with curative properties). -

![Plamen Pavlov, the Forgotten Middle Ages], Българска История, София 2019, Pp](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6011/plamen-pavlov-the-forgotten-middle-ages-2019-pp-2886011.webp)

Plamen Pavlov, the Forgotten Middle Ages], Българска История, София 2019, Pp

520 Book reviews DOI: 10.18778/2084-140X.10.26 ПЛАМЕН ПАВЛОВ, Забравеното Средновековие [Plamen Pavlov, The Forgotten Middle Ages], Българска История, София 2019, pp. 303. ast year, Plamen Pavlov – an outstand- вековна България [Kuber and the “double be- L ing Bulgarian researcher and promoter ginning” of medieval Bulgaria] (p. 11–19). It is of knowledge about medieval (but not only) devoted to the role of the so-called Kuber’s Bul- Bulgaria1, for years associated with the Uni- garia (located in Macedonia), little known to versity of Saints Cyril and Methodius in Veliko the average reader, in the process of establish- Tǎrnovo – published a book entitled Забраве- ing the medieval Bulgarian state. ното Средновековие [The Forgotten Middle The protagonist of the next text Кан Тервел Ages], the purpose of which was to familiarize и неговите съвременници [Khan Tervel and a wide range of readers with less known issues his contemporaries] (p. 20–28) is Khan Tervel related to the Bulgarian Middle Ages. The book (700–720), successor of Asparuh (the founder consists of twenty-five texts. Some of them had of Danubian Bulgaria). The author also reflects already been published (but have been reviewed on the rulers (of Byzantium, the Arabs, Khaz- and supplemented by the author); others have ars) as well as leaders with whom Tervel came “premiered” in the discussed book. into contact (especially during the Arabs’ siege The Forgotten Middle Ages opens with the of Constantinople in the years 717–718). Pavlov text Кубер и „двойното начало” на средно- claims that Tervel deserves a prominent place in the pantheon of European heroes who de- 1 P. -

PW06 Copertina R OK C August 20-28,2004 Florence -Italy

Volume n° 6 - from P55 to PW06 32nd INTERNATIONAL GEOLOGICAL CONGRESS GEOLOGICAL AND GEOTECHNICAL HAZARDS OF MAJOR NATURAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL MONUMENTS Conveners: I. Bruchev, G. Frangov, N. Dobrev, A. Lakov Field Trip Guide Book - PW06 Field Trip Florence - Italy August 20-28, 2004 Post-Congress PW06 PW06_ copertina_R_OK C 21-06-2004, 11:15:54 The scientific content of this guide is under the total responsibility of the Authors Published by: APAT – Italian Agency for the Environmental Protection and Technical Services - Via Vitaliano Brancati, 48 - 00144 Roma - Italy Series Editors: Luca Guerrieri, Irene Rischia and Leonello Serva (APAT, Roma) English Desk-copy Editors: Paul Mazza (Università di Firenze), Jessica Ann Thonn (Università di Firenze), Nathalie Marléne Adams (Università di Firenze), Miriam Friedman (Università di Firenze), Kate Eadie (Freelance indipendent professional) Field Trip Committee: Leonello Serva (APAT, Roma), Alessandro Michetti (Università dell’Insubria, Como), Giulio Pavia (Università di Torino), Raffaele Pignone (Servizio Geologico Regione Emilia-Romagna, Bologna) and Riccardo Polino (CNR, Torino) Acknowledgments: The 32nd IGC Organizing Committee is grateful to Roberto Pompili and Elisa Brustia (APAT, Roma) for their collaboration in editing. Graphic project: Full snc - Firenze Layout and press: Lito Terrazzi srl - Firenze PW06_ copertina_R_OK D 3-06-2004, 10:24:30 Volume n° 6 - from P55 to PW06 32nd INTERNATIONAL GEOLOGICAL CONGRESS GEOLOGICAL AND GEOTECHNICAL HAZARDS OF MAJOR NATURAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL MONUMENTS AUTHORS: I. Bruchev, G. Frangov, N. Dobrev, A. Lakov (Geological Institute, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofi a - Bulgaria) Florence - Italy August 20-28, 2004 Post-Congress PW06 PW06_R_OK A 3-06-2004, 10:27:44 Front Cover: Rock relief of the Madara Horseman PW06_R_OK B 3-06-2004, 10:27:46 GEOLOGICAL AND GEOTECHNICAL HAZARDS OF MAJOR NATURAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL MONUMENTS PW06 Conveners: I. -

Studia Academica Šumenensia

THE UNIVERSITY OF SHUMEN THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY STUDIA ACADEMICA ŠUMENENSIA THE EMPIRE AND BARBARIANS IN SOUTH-EASTERN EUROPE IN LATE ANTIQUITY AND EARLY MIDDLE AGES edited by Stoyan Vitlyanov and Ivo Topalilov Vol. 1, 2014 The University of Shumen Press STUDIA ACADEMICA ŠUMENENSIA THE UNIVERSITY OF SHUMEN THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY edited by Stoyan Vitlyanov and Ivo Topalilov ISSN 2367-5446 THE UNIVERSITY OF SHUMEN PRESS Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................5 The portrait of Flavius Aetius (390-454) from Durostorum (Silistra) inscribed on a consular diptych from Monza ....................................................................7 Georgi Atanasov And now, what’s going to happen to us without barbarians? ........................22 Monika Milosavljević German discoveries at Sucidava-Celei in the 6th century ..............................39 Dorel Bondoc Mirela Cojoc The beginnings of the Vandals settlement in the Danube area ......................51 Artur Błażejewski Observations on the Barbarian presence in the province of Moesia Secunda in Late Antiquity ...................................................................................................65 Alexander Stanev Two bronze late antique buckles with Christian inscriptions in Greek from Northeast Bulgaria ............................................................................................87 Totyu -

The Macedonian National Movement in the Pirin Part of Macedonia

Atanas Kiryakov and Aleksandar Donski MACEDONIA RISES THE MACEDONIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT IN THE PIRIN PART OF MACEDONIA 1 Atanas KIRYAKOV and Aleksandar DONSKI MACEDONIA RISES THE MACEDONIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT IN THE PIRIN PART OF MACEDONIA Published by the Macedonian Literary Association “Grigor Prlichev”, Sydney – Australia In collaboration with Institute for History and Archaeology “Goce Delcev” University - Stip Republic of Macedonia For the Publisher: Dushan RISTEVSKI * * * Translated by: Ljubica Bube DONSKA David RILEY (Great Britain) *** Macedonian Literary Association “Grigor Prlichev” P.O. Box 227 Rockdale NSW 2216 – Australia * * * Copyright by: Atanas Kiryakov and Aleksandar Donski National Library of Australia card number and ISBN 978-0-9808479-8-7 December, 2012 2 The book that you have in front of you presents a part of the documentation from the personal archive of the Macedonian activist Atanas Kiryakov from Blagoevgrad, which is dedicated to the struggle for the basic human and national rights of the Macedonians in the Pirin part of Macedonia and Bulgaria. People and events that Kiryakov himself directly or indirectly has met or attended are mentioned in here. This means that the book does not claim to contain ALL the documents from the struggles of the Macedonians under Pirin or that it contains all Macedonian activities, so the rest of the documents, notable people and descriptions of this struggle, remain to be published in later issues. From the editors 3 MAIN SPONSOR OF THE BOOK: Macedonian Orthodox Community of Australia 4 INSTEAD OF AN INTRODUCTION Before we move on to the basic subject of this book, we have to explain why the Macedonians were never Bulgarian, nor did they have ethnic Bulgarian origins, as it is claimed by the majority of Bulgarian governments and official organs. -

Sayı / Issue: 16 Kazakistan’In Nükleer Mirası Kazakhstan’S Nuclear Heritage

İSTANBUL AYDIN ÜNİVERSİTESİ UYGULAMA GAZETESİ / ISTANBUL AYDIN UNIVERSITY PERIODICAL JOURNAL 1 Aralık-1 Ocak 2012-2013 / 1st December – 1st January 2012-2013 türkİye’De Bir İşbİrlİğİne Devam bölGesel “bİrlİk” büyük sermaye BANKALAR, İlk ‘turİzm ve İçİn İlk adım: Gözünü toprağa KRİz VE POLİtİKA Dİktİ Gastronomİ’ türkİye, MısIr ve Dünya, akaDemİsİ protokolü yenİ orta Doğu 10 bankanIn esİrİ! İmzalandı a FIrst In turkey: CooperatIon FIrst step towarDs bIG CapItal FIxeD BANKS, CrISES AND the ‘tourIsm anD Goes on reGIonal “unIon”: eyes on the soİl POLICy Gastronomy’ turkey, Egypt, anD the worlD AcaDemy protoCol Is the new mIddle east Is helD CaptIve SigneD by 10 banks! Amerikanın Sesi İrahim Kalın Vicent Boix Zhang Danhong 02 03 04 06 09 Sayı / Issue: 16 KazaKistan’ın nüKleer Mirası Kazakhstan’s Nuclear Heritage euronews azakistan dünyada topraklarında en fazla azakhstan is one of the countries in the world radyasyon barındıran ülkelerden biri. Eski which contains the most radiation in its soil. Sovyetler Birliği döneminde Kazakistan top- It is stated that 237 million tons of radioacti- Kraklarına 237 milyon ton radyoaktif atık gömüldüğü Kve waste was buried in the soil of Kazakhstan during the belirtiliyor. Ülkede Sovyet döneminde binlerce nük- Former Soviet Union period. Thousands of nuclear tests leer deneme yapıldı. Bu denemelerde büyük miktar- were made in this country during the Soviet era. Huge larda radyasyon açığa çıktı. İkinci Dünya Savaşı’nın amounts of radiation came out during these tests. The ra- sonunda Hiroşima’ya atılan atom bombasının açığa diation is mentioned to be equal to 20 thousand times the çıkardığının 20 bin katına eşit miktarda radyasyonun one given off by the atom bomb dropped on Hiroshima varlığından söz ediliyor. -

TUNA BULGAR DEVLETİNİN İLK ASRI Koruyamamaları Ve Hazarlar Kar�Isında Mağlup Olmaları Gösterilir

Türk Dünyası Đncelemeleri Dergisi / Journal of Turkish World Studies, X/2 (Kı ş 2010), s.1-18. TTTUNA BBBULGAR DDDEVLETİNİN İİİLK AAASRI: BBBALKANLARDA TTTUTUNMA VE PPPEKİŞME (681(681----803)803) ∗ Osman KARATAY ÖZET Bir Türk topluluğu olan Bulgarlar, Karadeniz ve Kafkasların kuzeyindeki büyük devletleri yıkıldıktan sonra etrafa dağıl- mılar, bunlardan bir kol da Aşağı Tuna boylarına gelerek Bi- zans’tan aldığı Dobruca-Deliorman bölgesine yerlemitir. Bi- zans tarihinde ilk kez bu kadar yakın bir yerde yabancı bir devletin kuruluşu İstanbul’da kabullenilememi, iki devlet arasında kesintisiz bir mücadele başlamıtır. 680’lerden itiba- ren Bizans’ın çok güçlü hükümdarlar çıkaramayıı, buna kar- ılık Tuna Bulgar’ın ilk iki hükümdarının güçlü kişilikler olu- u sayesinde bu Türk devleti Balkanların doğusunda tutun- mutur. 8. yy ortalarından itibaren 20 yıllık bir dönem Bulgar devleti açısından bir fetret ve sarsıntı dönemi olarak niteleni- yor, ancak Bizans karısında hiç geri adım atmayıları hem sandığımız kadar kötü durumda olmadıklarını, hem de devle- tin temellerinin sağlam kurulduğunu göstermektedir. Aynı yüzyılın sonunda Bulgarlar yeniden yükseldiklerinde Bizans karısında mutlak güç sahibiydiler. Anahtar kelimelerkelimeler: Tuna Bulgarları, Bulgar hanları, Bizans, Asparuh, Tervel, Kardam. ABSTRACT The Bulgars, a Turkic people in Eastern Europe, were scat- tered around after the collapse of their empire in the North of the Black Sea and the Caucasus. A branch of them came to the Lower Danube banks and seized the Dobrogea-Teleorman re- gion from Byzantium. The latter could not accept such a case as establishing a ‘barbarous’ state just near to İstanbul, and the two state engaged in a continuous quarrel. That Byzantium had no authoritative personalities at the top, and that the first two Bulgar khans were superior rulers provided the Danubian ∗ Doç. -

Bulgar Tarihyaziminda Ii. Bulgar Devletinin Kuruluşu Ve Kuman/Kipçaklar

T.C. İSTANBUL ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANABİLİM DALI GENEL TÜRK TARİHİ BİLİM DALI DOKTORA TEZİ BULGAR TARİHYAZIMINDA II. BULGAR DEVLETİNİN KURULUŞU VE KUMAN/KIPÇAKLAR FATMA RODOPLU TEZ DANIŞMANI PROF. DR. MUALLA UYDU YÜCEL İSTANBUL, 2019 II ÖZ II. BULGAR DEVLETİ’NİN KURULUŞUNDA KUMAN/KIPÇAKLARIN ROLÜ FATMA RODOPLU Türk boyları içinde etkili ve dinamik bir boy olan Kuman/Kıpçaklar, tarihteki hareket alanları ve yayılma sahalarına bakıldığında geniş bir coğrafyada önemli izler bırakmışlardır. Kısa bir süre içerisinde Rus bozkırları üzerinden Balkanlara ulaşarak bu bölge siyaseti üzerinde önemli roller üstlenmeyi başarmışlardır. Bizans hâkimiyetinde bulunan Bulgaristan coğrafyasının kuzeyinde XII. yüzyılın son çeyreğinde büyük ölçüde ekonomik nedenlere dayanan bir ayaklanma çıkmış ve bu ayaklanmaya Kuman/Kıpçak asıllı Asen ve Peter adındaki iki kardeş öncülük etmişlerdir. Bu isyanın sonucu bölgedeki Kuman/Kıpçak, Bulgar ve Ulahlara özgürlük getirmiş ve II. Bulgar Devleti’nin bağımsızlığı ile sonuçlanmıştır. Yapılan birçok çalışma, Kuman/Kıpçaklar olmadan bu ayaklanmanın başarıya ulaşamayacağını göstermektedir. XIII-XIV. yüzyıllarda yine aynı devlette iktidarda olan Terter ve Şişman hanedanları da Kuman/Kıpçak kökenlidir. Döneme ait kaynaklarda Kuman/Kıpçakların bölgede oynadığı askeri ve siyasi önem açıkça görülmektedir. Ayrıca etnik olarak da bu coğrafyanın şekillenmesinde Kuman/Kıpçakların rolünün olduğu tarihi bir gerçektir. Bulgar tarihçilerin konuya ilişkin yaklaşımları ise siyasi konjonktöre bağlı olarak değişiklik göstermiştir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Kuman/Kıpçak, II. Bulgar Devleti, Bulgar tarihi, Tarihyazımı III ABSTRACT ESTABLISHMENT OF THE SECOND BULGARIAN KINGDOM AND CUMANS/KIPCHAKS IN BULGARIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY FATMA RODOPLU The Cumans, which have an effective and dynamic aspect within the Turkish tribes, left important traces in a wide geography when the fields of their action and span in history were examined. -

Kick-Off Conference Of

Common borders. Common solutions. Research of the tourist potential in the Black Sea Region Bulgaria www.greethis.net Content 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 5 1. Green and Historic Tourism trends in Bulgaria .......................................... 6 1.1. Marine Strategy of Republic of Bulgaria ............................................... 6 1.2. The Black Sea region in Bulgaria ................................................... 6 1.2.1. Climate ............................................................................. 7 1.2.2. Seismicity and landslide processes ............................................. 8 1.2.3. Transport and connectivity ...................................................... 8 1.2.4. Energy corridors ................................................................... 9 1.2.5. Tourism – culture, natural phenomenum, historical heritage .............. 9 1.2.6. Maritime tourism ................................................................. 10 1.2.7. Fisheries and aquaculture ...................................................... 11 1.2.8. Natural resources ................................................................ 12 1.2.9. Economic capacity of the moaritime zone ................................... 13 1.2.10. Spatial planning, coastal zone protection, environment ............... 13 2. GREEN HISTORIC/CULTURAL TOURISM INFRASTRUCTURE ............................. 19 2.1. Strategic Action Plan for environmental protection and rehabilitation -

PHARE Grant Tables with Beneficiaries

Phare 2004 Grants table list Name Page Grants awarded under Call for Proposals BG2004/016-711.11.04/ESC/G/CGS published on 24 February 2006 25 Grants awarded under Call for Proposals BG2004/016-711.11.04/ESC/G/GSC-1 published on 07 July 2006 654 Схема за безвъзмездна помощ за стимулиране на публично-частното партньорство 854 GRANT CONTRACTS AWARDED DURING April - November 30th, 2006 905 Grants awarded without a Call for Proposals - BG 2004/016-919.05.01.01 - Support for participation of the 920 Republic of Bulgaria in Community Initiative Interreg III B (CADSES) and Interreg III C Programme Grants awarded under Call for Proposals: BG2004/016-715.02.01: Joint Small Projects Fund between 952 Republic of Bulgaria and Republic of Turkey, published on April 3rd 2006 Grants awarded under Call for Proposals: BG 2004/016-782.01.02/GS: People to People in Actions in Support for Economic Development and Promotion of Employment between Republic of Bulgaria and Republic of 967 Greece, published on March 30th 2006 Grants awarded under Call for Proposals: BG2004/016-782.01.03-03/Grants: Promotion of Nature Protection Actions and Sustainable Development across the border, Republic of Bulgaria and Republic of Greece, 991 published on July 10th 2006 Grants awarded under Call for Proposals: BG2004/016-782.01.06.03/Grants: Promotion of the Cultural, Tourist and Human resources in the Cross-Border region, Republic of Bulgaria and Republic of Greece, published on 1007 July 10th 2006 Grants awarded under Call for Proposals: BG2004/016-783.01.03.01*Grants: Joint Small Project Funds , 1037 Republic of Bulgaria and Republic of Romania, published on July 10th 2006.