Studia Academica Šumenensia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electric Power Lines and Bird Conservation Along the Danube River

DANUBEPARKS Position Paper: Electric Power Lines and Bird Conservation along the Danube River Project co-funded by the European Union (ERDF, IPA funds) DANUBEparksCONNECTED ,PSULQW In cooperation with BirdLife Österreich and Danube Delta National Institute Editing & Text: Remo Probst (BirdLife Austria), Alexandru Dorosencu (Danube Delta National Institute) & Georg Frank (DANUBEPARKS) Contributions: Stephanie Blutaumüller, Walter Böhmer, Gabriela Cretu, Attila Fersch, Andrea Froncova, 0ECłNA@$AEnHAN )Q?E=!AQPO?DKR¹ *=NAG$¹HEO $UQH=(EOO $=>NEAH=*KNKVKR 1E>KN*EGQĊG= &KJ*QJPA=JQ 1E>KN-=NN=C "IEHEU=-APGKR= 3HP=GK/KĜ=? 1DKI=O0?DJAE@AN Layout: Maps:HAT=J@QN!KNKOAJ?Q !=IEN*=OE?Ġ!+2"-/(0 /=LD=AH-NEJVĠ!+2"-/(0 Cover Pictures: Georg Frank (DANUBEPARKS) Proofreading: Benjamin Seaman Print:(KJPN=OVP-HQOV(BP 1DEOLNKFA?PEO?KBQJ@A@>UPDA"QNKLA=J2JEKJĠ"/!# &-BQJ@O KLUNECDPNAOANRA@ © DANUBEPARKS 2019 DANUBEparksCONNECTED 7DEOHRIFRQWHQWV Synopsis and aims of the Position Paper4 Birds and power lines – introductory background5 4HEÒ$ANUBEÒkÒFACTSÒANDÒµGURES7 -NKłHA 7 =?G>KJABKN>EK@ERANOEPU7 0PQ@U=NA=8 Power line network10 Current knowledge13 Expert assessment and potential impacts14 Current mitigation measures14 Prioritisation of protection measures Need for prioritisation Collision Electrocution23 Bird-friendly solutions25 -NAHEIEJ=NUAT=JEI=PEKJO=J@LNKFA?P=OOAOOIAJPO25 +AA@O=J=HUOEO=J@HAC=H>=?GCNKQJ@25 3=NE=JP?DA?G25 New construction or conversion Construction versus operation phase 1A?DJE?=HOKHQPEKJO=C=EJOP?KHHEOEKJ 2J@ANCNKQJ@?=>HEJC -

Bu Belge Masonlar.Org Adresinden Indirilmistir Bu Belge Masonlar.Org

BuBu Belge Belge Masonlar.org Masonlar.org Adresinden Adresinden Indirilmistir Indirilmistir 1 BuBu Belge Belge Masonlar.org Masonlar.org Adresinden Adresinden Indirilmistir Indirilmistir BİZİMKİLER Anadolu Merkezli Dünya Tarihi 7. KİTAP M.S. 700 – M.S. 860 Müslüman İmparatorluğu Yazarlar Evin Esmen Kısakürek Arda Kısakürek 2 BuBu Belge Belge Masonlar.org Masonlar.org Adresinden Adresinden Indirilmistir Indirilmistir BİZİMKİLER............................................................................................................................. 2 7. KİTAP .................................................................................................................................... 2 Doğu Türükler Batıya Yürüyor.............................................................................................. 5 Doğu Roma’da Taht Kavgaları .............................................................................................. 8 Ceyhun’u Geçmek.................................................................................................................. 9 Hazar Roma Üzerinde Etkin ................................................................................................ 11 Araplar İspanya’da ............................................................................................................... 13 VII. Yüzyıl Asya’sı .............................................................................................................. 14 Şinto .................................................................................................................................... -

Organisations - Bulgaria

Organisations - Bulgaria http://www.herein-system.eu/print/194 Published on HEREIN System (http://www.herein-system.eu) Home > Organisations - Bulgaria Organisations - Bulgaria Country: Bulgaria Hide all 1.1.A Overall responsibility for heritage situated in the government structure. 1.1.A Where is overall responsibility for heritage situated in the government structure? Is it by itself, or combined with other areas? Ministry's name: Ministry of Culture Overall responsibility: Overall responsibility Ministerial remit: Cultural heritage Culture Heritage 1.1.B Competent government authorities and organisations with legal responsibilities for heritage policy and management. Name of organisation: National Institute for Immovable Cultural Heritage Address: 7, Lachezar Stantchev str. Post code: 1113 City: Sofia Country: Bulgaria Website: www.ninkn.bg E-mail: [email protected] Approx. number of staff: 49.00 No. of offices: 1 Organisation type: Agency with legal responsibilities Governmental agency Approach Integrated approach Main responsibility: Yes Heritage management: Designation Permits Site monitoring Spatial planning Policy and guidance: Advice to governments/ministers Advice to owners 1 of 31 04/05/15 11:29 Organisations - Bulgaria http://www.herein-system.eu/print/194 Advice to professionals Legislation Support to the sector Research: Documentation Field recording (photogrammetry..) Inventories Post-excavation analysis Ownership and/or management No (maintenance/visitor access) of heritage properties: Learning and communication: Communication -

Rationalising Sexual Morality in Western Christian Discourses, AD 390 – AD 520

Deviance and Disaster: Rationalising sexual morality in Western Christian discourses, AD 390 – AD 520 Ulriika Vihervalli School of History, Archaeology and Religion Cardiff University Presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2017 Abstract This thesis argues that the transition from traditional Roman ideas of sexual behaviour to idealised Christian sexual behaviour was a reactionary process, for which the period from AD 390 to AD 520 offers a crucial key stage. During this era, the Roman West underwent significant socio-political changes, resulting in warfare and violent conflict, which created a pressurised and traumatic environment for people who endured them. In this context, the rhetoric of divine punishment for sinful behaviour was stron gly linked with sexual acts, causing ideas on sexual mores to develop. The thesis highlights three key aspects of these developments. Firstly, warfare necessitated changes in Christian doctrines on marriages and rape, resulting from collective and cultural trauma. Secondly, sexually impure acts of incest and prostitution were defiling to the religious collective yet the consequences of these were negotiated on a case-to-case basis, reflecting adaptation. Thirdly, traditional Roman ideas of polygyny and homosexual acts overrode Christian ideas on the same. After discussing these three aspects, this work offers a revised interpretation of Salvian of Marseilles’s De gubernatione Dei to illuminate the purpose of the sexual polemic contained in his work – a task that no existing scholarship has attempted to undertake. Daily realities and conflicts drove discourses on sexual mores forwards, and this thesis outlines how this occurred in practice, arguing that attitudes to sex were deeply rooted in secular contexts and were reactionary in nature. -

Epidemiological Features of Suicides in Osijek County, Croatia, from 1986 to 2000

Coll. Antropol. 27 Suppl. 1 (2003) 101–110 UDC 616.89-008.441.44(497.5) Original scientific paper Epidemiological Features of Suicides in Osijek County, Croatia, from 1986 to 2000 Mladen Marciki}1, Mladen Ugljarevi}1, Tomislav Dijani}1, Boris Dumen~i}1 and Ivan Po`gain2 1 Department of Pathology and Forensic Medicine, University Hospital »Osijek», Osijek, Croatia 2 Department of Psychiatry, University Hospital »Osijek», Osijek, Croatia ABSTRACT Suicide is a devastating tragedy associated with social, cultural and psychological factors. It takes approximately 1,060 lives in the Republic of Croatia each year. We retro- spectively reviewed all cases referred to in the Registrar office and Police Department at Osijek County from 1986 to 2000. The cases of suicide totaled 1,017. All of the cases were analyzed as to age, gender, marital status, occupation, place and time of suicide and method of suicide. The suicide rate for the entire population of the County averaged 20.5/100,000 inhabitants per annum. The age of the suicides ranged from 15 to 92. The male to female ratio was 2.1:1. The highest suicide incidence was among the age groups from 55 to 64 (19.27%), followed by age group from 45 to 54 (16.12 %). The lowest sui- cide incidence was among the age group <19 (3.4%). The incidence in the group 85> years was also low (2.06%). The suicide was frequent among people who live alone: sin- gle, widowed, divorced (47.29%). Eighty percent of victims were found in surroundings familiar to them. These included various premises of their residences. -

Frontiers of the Roman Empire Граници На Римската Империя

FRE_PL_booklet_final 5/25/08 9:36 AM Page 1 Frontiers of the Roman Empire Граници на Римската империя David J Breeze, Sonja Jilek and Andreas Thiel The Lower Danube Limes in Bulgaria Долнодунавския лимес в България Piotr Dyczek with the support of Culture 2000 programme of the European Union Warsaw/Варшавa – Vienna/Виена 2008 FRE_PL_booklet_final 5/25/08 9:36 AM Page 2 Front cover/Корица Altar dedicated to Asclepios by the 1st Italic legion, discovered in front of the chapel of healing gods in the valetudinarium at Novae Олтар дарен на Асклетий от I Италийски легион, открит пред cветилище (sacellum) на лекуващи богове в valetudinarium в Novae The authors/Автори Professor David Breeze was formerly Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments in Historic Scotland prepared the nomination of the Antonine Wall as a World Heritage Site. Проф. Дейвид Брийз, изпълняващ функцията Главен Консерватор в Шотландия, е приготвил Стената на Антонинус за вписване в списъка с Паметници на световното наследство. Dr Sonja Jilek is the archaeological co-ordinator of the international "Frontiers of the Roman Empire Culture 2000 Project" Д-р Соня Илек – археолог – координатор на международния научен проект "Граници на Римската империя" – програма Culture 2000 Dr Andreas Thiel is the secretary of the German Limeskommission (2005–2008) Д-р Андреъс Тиел е секретар на Немската комисия по лимеса (2005 – 2008) Professor Piotr Dyczek (University of Warsaw) - Director of the Center for Research on the Antiquity of Southeastern Europe, Head of the Department for Material Culture in Antiquity at the Institute of Archaeology. Fieldwork supervisor in Tanais (Russia) and Serax (Turkmenistan). -

PDF Website Archelogia Bulga

ARCHAEOLOGIA BULGARICA XV 2011 #3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTICLES Nankov, E.: Berenike Bids Farewell to Seuthes III: e Silver-Gilt Scallop Shell Pyxis from the Golyama Kosmatka Tumulus ........................................................................................1 Radoslavova, G. / Dzanev, G. / Nikolov, N.: e Battle at Abritus in AD 251: Written Sources, Archaeological and Numismatic Data ...........................................................................................23 Curta, F. / Gândilă, A.: Too Much Typology, Too Little History: A Critical Approach to the Classi cation and Interpretation of Cast Fibulae with Bent Stem..............................................51 Cholakov, I. / Chukalev, K.: Statistics on the Archaeological Surveys in Bulgaria, 2006-2010 ..........................83 REVIEWS ARCHAEOLOGIA BULGARICA appears three times a year (20 x 28 cm, ca. 100 pages per number) and Slawisch, A.: Die Grabsteine der römischen Provinz racia. Aufnahme, Verarbeitung und Weitergabe provides a publishing forum for research in archaeology in the broadest sense of the term. ere are no überregionaler Ausdrucksmittel am Beispiel der Grabsteine einer Binnenprovinz zwischen Ost und West. restrictions as to time and territory but the emphasis is on Southeastern Europe. Beier & Beran, Langenweißbach, 2007. (Ivanov, M.) ................................................................................................97 Objective: interdisciplinary research of archaeology. Contents: articles and reviews. Languages: English, German -

Committee on Regional Development the Secretariat

COMMITTEE ON REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT THE SECRETARIAT October 2008 REPORT of the Committee on Regional Development's Delegation to Bulgaria from 30 September to 2 October 2008 European Parliament - Committee on Regional Development - The Secretariat SUMMARY Visit to Bulgaria to meet with Government Ministers and officials as well as the leaders of local administrations responsible for regional Subject development projects. Under the 2006 regulations the whole of Bulgaria qualifies for assistance under the Convergence objective. The field missions had the following main objectives: - To discuss with Ministers, relevant officials and local authorities the future implementation of the Regional development Operational Programme and sectoral programmes as well as to discuss with them any problems they may have. Main objectives - To acquaint members of the delegation with the specific problems of Bulgaria and see in situ some successful projects executed with pre-accession funds and discuss the implementation of operational programmes which are just starting up. Date 30 September to 02 October 2008 Sofia, Gorna Orjahovica, Arbanasi, Balchik, Varna Places Chairman Gerardo Galleote, Chair of the Regional Development Committee. The list of participants is attached in the annex. 2 of 11 European Parliament - Committee on Regional Development - The Secretariat BACKGROUND On the initiative of the Bulgarian Vice President of the Committee on Regional Development Mr Evgeni KIRILOV (PSE), the committee decided to send a delegation to Bulgaria. It was the last out of three delegation trips of the REGI Committee scheduled for 2008. Bulgaria is of particular interest to the Members of the Regional Development Committee for a number of reasons: Together with Romania, Bulgaria is the first Balkan country to join the European Union in the latest phase of the ongoing enlargement process. -

Gothic Introduction – Part 1: Linguistic Affiliations and External History Roadmap

RYAN P. SANDELL Gothic Introduction – Part 1: Linguistic Affiliations and External History Roadmap . What is Gothic? . Linguistic History of Gothic . Linguistic Relationships: Genetic and External . External History of the Goths Gothic – Introduction, Part 1 2 What is Gothic? . Gothic is the oldest attested language (mostly 4th c. CE) of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European family. It is the only substantially attested East Germanic language. Corpus consists largely of a translation (Greek-to-Gothic) of the biblical New Testament, attributed to the bishop Wulfila. Primary manuscript, the Codex Argenteus, accessible in published form since 1655. Grammatical Typology: broadly similar to other old Germanic languages (Old High German, Old English, Old Norse). External History: extensive contact with the Roman Empire from the 3rd c. CE (Romania, Ukraine); leading role in 4th / 5th c. wars; Gothic kingdoms in Italy, Iberia in 6th-8th c. Gothic – Introduction, Part 1 3 What Gothic is not... Gothic – Introduction, Part 1 4 Linguistic History of Gothic . Earliest substantively attested Germanic language. • Only well-attested East Germanic language. The language is a “snapshot” from the middle of the 4th c. CE. • Biblical translation was produced in the 4th c. CE. • Some shorter and fragmentary texts date to the 5th and 6th c. CE. Gothic was extinct in Western and Central Europe by the 8th c. CE, at latest. In the Ukraine, communities of Gothic speakers may have existed into the 17th or 18th century. • Vita of St. Cyril (9th c.) mentions Gothic as a liturgical language in the Crimea. • Wordlist of “Crimean Gothic” collected in the 16th c. -

Dejan Radičević, Perica Špehar Some Remarks on Hungarian Conquest Period Finds

ACTA ARCHAEOLOGICA CARPATHICA VOL. L, 2015 PL ISSN 0001-5229 Dejan RaDičević, PeRica ŠPehaR SOME REMARKS ON HUNGARIAN CONQUEST PERIOD FINDS IN VOJVODINA ABSTRACT D. Radičević, P. Špehar 2015. Some remarks on Hungarian Conquest Period Finds in Vojvodina, AAC 50: 137–162. The last reviews of sites and finds dated to the 10th and 11th centuries on the territory of modern Vojvodina were made quarter of century ago. Development of the methodology of archaeological investigations, re-examination of old and appearance of new sites and finds, as well as the ongo- ing evaluation of the results of archaeologically explored necropolis in Batajnica, all suggested the necessity for a work dedicated to the problem of colonization of Hungarians as well as to the analyses of the phenomena typical for that period in Serbian part of Banat, Bačka and Srem. K e y w o r d s: Hungarian Conquest Period; Vojvodina; Batajnica; soil inhabitation; necropolis; warrior graves; horseman graves Received: 13.04.2015; Revised: 29.05.2015; Revised: 17.08.2015; Revised: 31.08.2015; Accepted: 10.11.2015 INTRODUCTION In Serbian archaeology insufficient attention is dedicated to the problem of inhabitation of Hungarians as well as to the research of ancient Hungarian material culture1. The reason lies in the fact that the territory of modern Vojvodina, in the time of more intense archaeological explorations of sites dated to the discussed period, was part of the Habsburg Monarchy. Archaeological material was sent mostly to the museums in Szeged or Budapest, so it became primarily the subject of interest of Hungarian specialists. -

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry Of

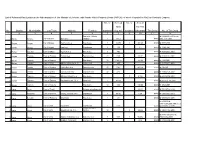

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry of Defence, with Private Public Property Deeds (PPPDs), of which Property the MoD is Allowed to Dispose No. of Built-up No. of Area of Area the Plot No. District Municipality City/Town Address Function Buildings (sq. m.) Facilities (decares) Title Deed No. of Title Deed 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Part of the Military № 874/02.05.1997 for the 1 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Slaveykov Hospital 1 545,4 PPPD whole real estate 2 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Kapcheto Area Storehouse 6 623,73 3 29,143 PPPD № 3577/2005 3 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Sarafovo Storehouse 6 439 5,4 PPPD № 2796/2002 4 Burgas Nesebar Town of Obzor Top-Ach Area Storehouse 5 496 PPPD № 4684/26.02.2009 5 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Honyat Area Barracks area 24 9397 49,97 PPPD № 4636/12.12.2008 6 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Storehouse 18 1146,75 74,162 PPPD № 1892/2001 7 Burgas Sozopol Town of Atiya Military station, by Bl. 11 Military club 1 240 PPPD № 3778/22.11.2005 8 Burgas Sredets Town of Sredets Velikin Bair Area Barracks area 17 7912 40,124 PPPD № 3761/05 9 Burgas Sredets Town of Debelt Domuz Dere Area Barracks area 32 5785 PPPD № 4490/24.04.2008 10 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Ahtopol Mitrinkovi Kashli Area Storehouse 1 0,184 PPPD № 4469/09.04.2008 11 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Tsarevo Han Asparuh Str., Bl. -

Harttimo 1.Pdf

Beyond the River, under the Eye of Rome Ethnographic Landscapes, Imperial Frontiers, and the Shaping of a Danubian Borderland by Timothy Campbell Hart A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Greek and Roman History) in the University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Professor David S. Potter, Co-Chair Professor Emeritus Raymond H. Van Dam, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Ian David Fielding Professor Christopher John Ratté © Timothy Campbell Hart [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-8640-131X For my family ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Developing and writing a dissertation can, at times, seem like a solo battle, but in my case, at least, this was far from the truth. I could not have completed this project without the advice and support of many individuals, most crucially, my dissertation co-chairs David S. Potter, and Raymond Van Dam. Ray saw some glimmer of potential in me and worked to foster it from the moment I arrived at Michigan. I am truly thankful for his support throughout the years and constant advice on both academic and institutional matters. In particular, our conversations about demographics and the movement of people in the ancient world were crucial to the genesis of this project. Throughout the writing process, Ray’s firm encouragement towards clarity of argument and style, while not always what I wanted to hear, have done much to make this a stronger dissertation. David Potter has provided me with a lofty academic model towards which to strive. I admire the breadth and depth of his scholarship; working and teaching with him have shown me much worth emulating.