The Texas-Cherokee War of 1839

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Eastern Cherokees

Cl)e LilJratp of ti>t Onlvjer^itp of Jl3ott6 Carolina Collection of iRottI) Catoliniana Hofin feprunt ^(11 of t^e Cla00 of 1889 H UNIVERSITY OF N C AT CHAPEL HILL 00030748843 This book must not be token from the Library building. Form No. 471 ^y 'S SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY The Eastern Cherokees By WILLIAM HARLEN GILBERT, Jr. Anthropological Papers, No. 23 From Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 133, pp. 169-413, pis. 13-11 ^,,,.1 SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY The Eastern Cherokees By WILLIAM HARLEN GILBERT, Jr. Anthropological Papers, No. 23 FromjBureau'of American Ethnology Bulletin 133, pp. 169-413, pb. 13-17 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1943 (2. '^ -f o.o S^ SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 133 Anthropological Papers, No. 23 The Eastern Cherokees By WILLIAM HARLEN GILBERT, Jr. 169 CONTENTS PAGE Preface 175 Introduction 177 Description of the present society 177 The environmental frame 177 General factors 177 Location 178 Climatic factors 182 Inorganic elements 183 Flora and fauna 184 Ecology of the Cherokees 186 The somatic basis 193 History of our knowledge of Cherokee somatology 193 Blood admixture 194 Present-day physical type 195 Censuses of numbers and pedigrees 197 Cultural backgrounds 198 Southeastern traits 198 Cultural approach 199 Present-day Qualla 201 Social units 201' Tlie town 201 The household 202 The clan 203 Economic units 209 Political units 215 The kinship system 216 Principal terms used 216 Morgan's System -

Creating a Sense of Communityamong the Capital City Cherokees

CREATING A SENSE OF COMMUNITYAMONG THE CAPITAL CITY CHEROKEES by Pamela Parks Tinker A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies Committee: ____________________________________ Director ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Program Director ____________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date:________________________________ Spring 2016 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Creating a Sense Of Community Among Capital City Cherokees A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies at George Mason University By Pamela Parks Tinker Bachelor of Science Medical College of Virginia/Virginia Commonwealth University 1975 Director: Meredith H. Lair, Professor Department of History Spring Semester 2016 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia Copyright 2016 Pamela Parks Tinker All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements Thanks to the Capital City Cherokee Community for allowing me to study the formation of the community and for making time for personal interviews. I am grateful for the guidance offered by my Thesis Committee of three professors. Thesis Committee Chair, Professor Maria Dakake, also served as my advisor over a period of years in planning a course of study that truly has been interdisciplinary. It has been a joyful situation to be admitted to a variety of history, religion and spirituality, folklore, ethnographic writing, and research courses under the umbrella of one Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies program. Much of the inspiration for this thesis occurred at George Mason University in Professor Debra Lattanzi Shutika’s Folklore class on “Sense of Place” in which the world of Ethnography opened up for me. -

Treaty Signers: Yellow Indicates Middle and Overhill, Red Letter Indicates Are Lower

Treaty Signers: Yellow indicates Middle and Overhill, Red Letter indicates are Lower Pre-American Revolution Treaty 1684 between two Cherokee towns with English Traders of Carolina, Established beginning a steady trade in deerskins and Indian slaves. Nation's leaders who signed were- Corani the Raven (Ka lanu): Sinnawa the Hawk (Tla nuwa): Nellawgitchi (possibly Mankiller): Gorhaleke: Owasta: all of Toxawa: and Canacaught, the Great Conqueror: Gohoma: Caunasaita of Keowee. Note: Majority of signers are actually Shawnee. Gorheleke Aka George Light Sky or Letsky better known as Bloody Fellow later commissioned by George Washington. This mixed signers. Treaty with South Carolina, 1721 Ceded land between the Santee, Saluda, and Edisto Rivers to the Province of South Carolina. Note: Settlers encroached violating Treaty Treaty of Nikwasi, 1730 Trade agreement with the Province of North Carolina through Alexander Cumming. Note: Cummings was not authorized by the crown to negotiate on behalf of England. He fled debtor’s prison to the colonies. Articles of Trade and Friendship, 1730 Established rules for trade between the Cherokee and the English colonies. Signed between seven Cherokee chiefs (including Attakullakulla) and George I of England. Note: No Cessions. Treaty with South Carolina, 1755 Ceded land between the Wateree and Santee Rivers to the Province of South Carolina. Note: Settlers encroached violating Treaty. Treaty of Long-Island-on-the-Holston, 1761 Ended the Anglo-Cherokee War with the Colony of Virginia. Note: Settlers encroached violating Treaty. Page 1 of 7 Treaty of Charlestown, 1762 Ended the Anglo-Cherokee War with the Province of South Carolina. No Cessions, Colonists continued to encroach. -

Occupying the Cherokee Country of Oklahoma

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska) University Studies of the University of Nebraska 1978 Occupying the Cherokee Country of Oklahoma Leslie Hewes University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/univstudiespapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Hewes, Leslie, "Occupying the Cherokee Country of Oklahoma" (1978). Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska). 30. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/univstudiespapers/30 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Studies of the University of Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Leslie Hewes Occupying the Cherokee Country of Oklahoma I new senes no. 57 University of Nebraska Studies 1978 Occupying the Cherokee Country of Oklahoma The University of Nebraska The Board of Regents JAMES H. MOYLAN ROBERT L. RAUN chairman EDWARD SCHWARTZKOPF CHRISTINE L. BAKER STEVEN E. SHOVERS KERMIT HANSEN ROBERT G. SIMMONS, JR. ROBERT R. KOEFOOT, M.D. KERMIT WAGNER WILLIAM J. MUELLER WILLIAM F. SWANSON ROBERT J. PROKOP, M.D. corporation secretary The President RONALD W. ROSKENS The Chancellor, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Roy A. YOUNG Committee on Scholarly Publications GERALD THOMPSON DAVID H. GILBERT chairman executive secretary J AMES HASSLER KENNETH PREUSS HENRY F. HOLTZCLAW ROYCE RONNING ROBERT KNOLL Leslie Hewes Occupying the Cherokee Country of Oklahoma university of nebraska studies: new series no. -

Major Ridge, Leader of the Treaty Party Among the Cherokees, Spent The

Historic Origins of the Mount Tabor Indian Community of Rusk County, Texas Patrick Pynes Northern Arizona University Act One: The Assassination of Major Ridge On June 21, 1839, Major Ridge, leader of the Cherokee Treaty Party, stopped to spend the night in the home of his friend, Ambrose Harnage. A white man, Harnage and his Cherokee family lived in a community called Illinois Township, Arkansas. Nancy Sanders, Harnage’s Cherokee wife, died in Illinois Township in 1834, not long after the family moved there from the Cherokee Nation in the east. Illinois Township was located right on the border between Arkansas and the new Cherokee Nation in the west. Ride one mile west, and you were in Going Snake District. Among the families living in Illinois Township in 1839 were some of my own blood relations: Nancy Gentry, her husband James Little, and their extended family. Nancy Gentry was the sister of my fifth maternal grandfather, William Gentry. Today, several families who descend from the Gentrys tell stories about their ancestors’ Cherokee roots. On June 21, 1839, Nancy Gentry’s family was living nine doors down from Ambrose Harnage. Peering deep into the well of time, sometimes hearing faint voices, I wonder what Major Ridge and his friend discussed the next morning at breakfast, as Harnage’s distinguished guest prepared to resume his journey. Perhaps they told stories about Andrew Sanders, Harnage’s brother-in-law. Sanders had accompanied The Ridge during their successful assassination mission at Hiwassee on August 9, 1807, when, together with two other men, they killed Double-head, the infamous Cherokee leader and businessman accused of selling Cherokee lands and taking bribes from federal agents. -

Becoming Indian

BECOMING INDIAN The Struggle over Cherokee Identity in the Twenty-first Century one Opening Often when we are about to leave a place, we find out what really matters, what peo- ple care about, what rattles around inside their hearts. So it was for me at the end of fourteen months of ethnographic fieldwork in Tahlequah, Oklahoma—the heart of the Cherokee Nation—where I lived in 1995 and 1996 and where I have returned on a regular basis ever since. On the eve of my first departure, a number of Cherokee peo- ple, particularly tribal employees, started directing my attention toward an intriguing and at times disturbing phenomenon. This is how in late April 1996 I found myself screening a video with five Cherokee Nation employees, two of whom worked in the executive offices, the others for the Cherokee Advocate, the official tribal newspaper.1 Several of them had insisted that if I was going to write about Cherokee identity pol- itics,2 I needed to see this particular video. A woman from the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina had shot the original footage, having traveled all the way to Portsmouth, Ohio, in July 1987 to record the unusual proceedings. The images she captured were so powerful that tribal employees in Oklahoma and North Carolina were still expressing confusion and resentment almost a decade later. Though it was in terrible shape from repeated dubbing, the video gripped our attention. Not only had it been shot surreptitiously, with the novice filmmaker and her companion posing as news reporters, but also our version was a copy of a copy of a copy that had been passed hand to hand, like some weird Grateful Dead bootleg, www.sarpress.sarweb.org 1 making its way through Indian country from the eastern seaboard to the lower Midwest. -

“If the Union Wins, We Won't Have Anything Left”

“If the Union Wins, We Won’t Have Anything Left”: The Rise and Fall of the Southern Cherokees of Kansas by Gary L. Cheatham ittle has been written about the Cherokees of Kansas and their settlement of the Cherokee Neutral Lands and Chetopa, Kansas, area. Contrary to the reports of some historians, a viable population of Cherokees lived on the Neutral Lands and other tribal members lived in the Chetopa area more than twenty years before statehood.1 Most of these American Indi- Lans came west as part of the “removed” southeastern United States tribes, comprised of Cherokees, Chickasaws, Choctaws, and Creeks. Thus, although the Cherokees were hardly the only eastern tribe to arrive in Kansas prior to statehood, their unique place in the early history of the state was largely forgotten after their departure, a process that began during the Civil War, and ended with the tribe’s postwar loss of its Kansas lands. Between 1825 and 1841 more than ten thousand Native Americans from more than a dozen northeastern tribes, such as the Shawnees, Delawares, and Sacs and Foxes, were relocated to that part of Indian territory destined to become Kansas. The Osages had Gary L. Cheatham is an assistant professor of library services at Northeastern State University, Tahlequah, Okla- homa. A native Kansan, he holds a Master of Divinity from Brite Divinity School at Texas Christian University, and a Master of Science in Library Science from the University of Tennessee-Knoxville. His research and publication interests include the early history of Kansas and the Great Plains. The author would like to thank Vickie Sheffler, NSU Archivist, for providing research assistance with the major Cherokee census rolls. -

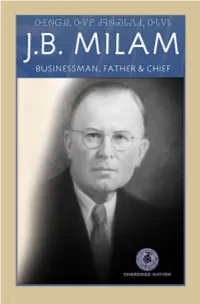

JB Milam Is on the Top Row, Seventh from the Left

Copyright © 2013 Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc. Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc, PO Box 515, Tahlequah, OK 74465 Design and layout by I. Mickel Yantz All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage system or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Businessman,J.B. Father,Milam Chief A YOUNG J. B. MILAM Photo courtesy of Philip Viles Published by Cherokee Heritage Press, 2013 3 J.B. Milam Timeline March 10, 1884 Born in Ellis County, Texas to William Guinn Milam & Sarah Ellen Couch Milam 1887, The Milam family moved to Chelsea, Indian Territory 1898, He started working in Strange’s Grocery Store and Bank of Chelsea 1899, Attended Cherokee Male Seminary May 24, 1902 Graduated from Metropolitan Business College in Dallas, TX 1903, J.B. was enrolled 1/32 degree Cherokee, Cherokee Roll #24953 1904, Drilled his first oil well with Woodley G. Phillips near Alluwe and Chelsea 1904, Married Elizabeth P. McSpadden 1905, Bartley and Elizabeth moved to Nowata, he was a bookkeeper for Barnsdall and Braden April 16, 1907 Son Hinman Stuart Milam born May 10, 1910 Daughter Mildred Elizabeth Milam born 1915 Became president of Bank of Chelsea May 16, 1916 Daughter Mary Ellen Milam born 1933 Governor Ernest W. Marland appointed Milam to the Oklahoma State Banking Board 1936 President of Rogers County Bank at Claremore 1936 Elected President of the Cherokee Seminary Students Association 1937 Elected to the Board of Directors of the Oklahoma Historical Society 1938 Elected permanent chairman for the Cherokees at the Fairfield Convention April 16, 1941 F.D.R. -

Twentieth Century Cherokee Property Claims: a Study Based on the Case Files of Earl Boyd Pierce Richard S

American Indian Law Review Volume 19 | Number 2 1-1-1994 Twentieth Century Cherokee Property Claims: A Study Based on the Case Files of Earl Boyd Pierce Richard S. Crump Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard S. Crump, Twentieth Century Cherokee Property Claims: A Study Based on the Case Files of Earl Boyd Pierce, 19 Am. Indian L. Rev. 507 (1994), https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr/vol19/iss2/8 This Special Feature is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPECIAL FEATURE TWENTIETH CENTURY CHEROKEE PROPERTY CLAIMS: A STUDY BASED ON THE CASE FILES OF EARL BOYD PIERCE Richard S. Crump* Cherokee property issues represent some of the most protracted claims in United States history. The purpose of this article is to demonstrate the procedural process involved in pressing tribal claims before the Indian Claims Commission and in federal court. The development of the Outlet cases, the Texas Cherokee claims, and the Freedman cases will be outlined. The Arkansas riverbed litigation, still pending, will also be explored. The historical data used in this study is primarily based on the files of Earl Boyd Pierce, who became the first full-time Cherokee tribal attorney in 1938. Pierce, Chief W.W. Keeler, and other great Cherokee warriors were responsible for organizing the Cherokee Nation's government as it exists today. -

Vol. 24 No. 1 Pioneer Beginnings at Emmanuel, Shawnee by The

Vol. 24 No. 1 Pioneer Beginnings at Emmanuel, Shawnee by the Reverend Franklin C. Smith -- 2 Mrs. Howard Searcy by Howard Searcy -------------------------------------------------- 15 Jane Heard Clinton by Angie Debo -------------------------------------------------------- 20 Mary C. Greenleaf by Carolyn Thomas Foreman --------------------------------------- 26 Memories of George W. Mayes by Harold Keith --------------------------------------- 40 The Hawkins’ Negroes Go to Mexico by Kenneth Wiggins Porter ------------------ 55 Oklahoma War Memorial – World War II by Muriel H. Wright ---------------------- 59 An Eighty-Niner Who Pioneered the Cherokee Strip by Lew F. Carroll ------------- 87 Notes and Documents ----------------------------------------------------------------------- 102 Book Reviews -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 108 Necrologies Cornelius Emmet Foley by Robert L. Williams -------------------------------- 112 William Leonard Blessing by Robert L. Williams ----------------------------- 113 Charles Arthur Coakley by Robert L. Williams -------------------------------- 114 James Buchanan Tosht by Rober L. Williams ---------------------------------- 115 William L. Curtis by D.B. Collums ---------------------------------------------- 116 Earl Gilson by Lt. Don Dale ------------------------------------------------------- 117 William Marshal Dunn by Muriel H. Wright ----------------------------------- 119 Minutes ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

DOCUMENT RESUME RC 003 557 TITLE Indian Education. Part 2

DOCUMENT RESUME ED C55 6" RC 003 557 TITLE Indian Education. Part 2, HearingsBefore the Special Subcommittee on Indian Education ofthe Committee on Labor and Public Welfare, UnitedStates Senate, Ninetieth Congress, First and SecondSessions on the Study of the Education of IndianChildren. INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington,D.C. Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare. PUB DATE 69 NoTE 297p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$9.87 DESCRIPTORS Achievement; *American Indians;Attitudes; Curriculum; *Education; *Federal Government; *Information Seeking; *Investigations;Racial Factors; Schools; Teachers IDENTIFIERS Cherokees ABSTRACT Hearings of the U.S. Senate'sSpecial Subcommittee on Indian Education--held at Twin Oaks,Okla., on Feb, 19, 1968--are recorded in this document, whichis Part 2 of the hearings proceedings (Part 1 is RC 003556; Part 3 is RC 003 558). Part2 contains Indian testimony (mainlyCherokee) about changes and improvements that must be made ifIndian children are to receive equal and effective education.Also included are articles, publications, and communicationsrelating to Oklahoma's Indians, as veil as learning materials (inCherokee and English) related to health education. (EL) INDIANEDUCATION cx) k- ,4) HEARINGS BEFORE THE ON tA) SPECIAL SUBCOMMITTEE INDIAN EDUCATION OF THE COMMITTEE ON LIBOR 8NDPUBLIC WEIPLU UNITED STATESSENATE NINETIETH CONGRF SS FIRST AND SECONDSESSIONS ON THE STUDY OF THEEDUCATION OF INDIAN CHILDREN PART 2 FEBRUARY 19, 1968 TV01,1"71"1":""til*. TWIN OAKS; OKLA. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN- IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU- CATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

The Creek Indians in East Texas

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 14 Issue 2 Article 7 10-1976 The Creek Indians in East Texas Gilbert M. Culbertson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Culbertson, Gilbert M. (1976) "The Creek Indians in East Texas," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 14 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol14/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 20 EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE CREEK INDIANS IN EAST TEXAS by Gilbert M, Culbertson Putting flesh on the barebones of historical documents is one of the great rewards of the historian. Vanished personalities spring from hidden places in a dance which is no longer macabre because it is real, Such is the ta",k of reconstructing the Texas past from the Hagerty-Dohoney papers which deal with the migration ofthe Greek Indians, Texas slaveholdings, and the settlement of Harrison and Red River counties. I Among the Indian tribes settled in Texas the Creeks were among the most civilized. Their correspondence is highly literate and their business transactions astute. There were indeed hazy legends of Madoc and 81. Brendan and tales of Welsh and Irish blood among the Cherokees and Creeks. In spite of their superior culture and leadership the removal from the ancestral lands ofGeorgia was a "trail of tears.