Becoming Indian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rahm Uaf 0006E 10262.Pdf

Deconstructing the western worldview: toward the repatriation and indigenization of wellness Item Type Thesis Authors Rahm, Jacqueline Marie Download date 23/09/2021 13:22:54 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/4821 DECONSTRUCTING THE WESTERN WORLDVIEW: TOWARD THE REPATRIATION AND INDIGENIZATION OF WELLNESS A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Jacqueline Marie Rahm, B.A., M.A. Fairbanks, Alaska December 2014 Abstract As Indigenous peoples and scholars advance Native histories, cultures, and languages, there is a critical need to support these efforts by deconstructing the western worldview in a concerted effort to learn from indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing for humanity’s future wellbeing. Toward that imperative, this research brings together and examines pieces of the western story as they intersect with Indigenous peoples of the lands that now comprise the United States of America. Through indigenous frameworks and methodologies, it explores a forgotten epistemology of the pre-Socratic and Pythagorean Archaic and Classical Greek eras that is far more similar to indigenous worldviews than it is to the western paradigm today. It traces how the West left behind this timeless wisdom for the “new learning” and the European colonial settlers arrived in the old “New World” with a fragmented, materialistic, and dualistic worldview that was the antithesis to those of Indigenous peoples. An imbalanced and privileged worldview not only justified an unacknowledged genocide in world history, it is characteristic of a psycho-spiritual disease that plays out across our global society. -

Native American Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Ethnozoology Herman A

IK: Other Ways of Knowing A publication of The Interinstitutional Center for Indigenous Knowledge at The Pennsylvania State University Libraries Editors: Audrey Maretzki Amy Paster Helen Sheehy Managing Editor: Mark Mattson Associate Editor: Abigail Houston Assistant Editors: Teodora Hasegan Rachel Nill Section Editor: Nonny Schlotzhauer A publication of Penn State Library’s Open Publishing Cover photo taken by Nick Vanoster ISSN: 2377-3413 doi:10.18113/P8ik360314 IK: Other Ways of Knowing Table of Contents CONTENTS FRONT MATTER From the Editors………………………………………………………………………………………...i-ii PEER REVIEWED Integrating Traditional Ecological Knowledge with Western Science for Optimal Natural Resource Management Serra Jeanette Hoagland……………………………………………………………………………….1-15 Strokes Unfolding Unexplored World: Drawing as an Instrument to Know the World of Aadivasi Children in India Rajashri Ashok Tikhe………………………………………………………………………………...16-29 Dancing Together: The Lakota Sun Dance and Ethical Intercultural Exchange Ronan Hallowell……………………………………………………………………………………...30-52 BOARD REVIEWED Field Report: Collecting Data on the Influence of Culture and Indigenous Knowledge on Breast Cancer Among Women in Nigeria Bilikisu Elewonibi and Rhonda BeLue………………………………………………………………53-59 Prioritizing Women’s Knowledge in Climate Change: Preparing for My Dissertation Research in Indonesia Sarah Eissler………………………………………………………………………………………….60-66 The Library for Food Sovereignty: A Field Report Freya Yost…………………………………………………………………………………………….67-73 REVIEWS AND RESOURCES A Review of -

The Eastern Cherokees

Cl)e LilJratp of ti>t Onlvjer^itp of Jl3ott6 Carolina Collection of iRottI) Catoliniana Hofin feprunt ^(11 of t^e Cla00 of 1889 H UNIVERSITY OF N C AT CHAPEL HILL 00030748843 This book must not be token from the Library building. Form No. 471 ^y 'S SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY The Eastern Cherokees By WILLIAM HARLEN GILBERT, Jr. Anthropological Papers, No. 23 From Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 133, pp. 169-413, pis. 13-11 ^,,,.1 SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY The Eastern Cherokees By WILLIAM HARLEN GILBERT, Jr. Anthropological Papers, No. 23 FromjBureau'of American Ethnology Bulletin 133, pp. 169-413, pb. 13-17 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1943 (2. '^ -f o.o S^ SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 133 Anthropological Papers, No. 23 The Eastern Cherokees By WILLIAM HARLEN GILBERT, Jr. 169 CONTENTS PAGE Preface 175 Introduction 177 Description of the present society 177 The environmental frame 177 General factors 177 Location 178 Climatic factors 182 Inorganic elements 183 Flora and fauna 184 Ecology of the Cherokees 186 The somatic basis 193 History of our knowledge of Cherokee somatology 193 Blood admixture 194 Present-day physical type 195 Censuses of numbers and pedigrees 197 Cultural backgrounds 198 Southeastern traits 198 Cultural approach 199 Present-day Qualla 201 Social units 201' Tlie town 201 The household 202 The clan 203 Economic units 209 Political units 215 The kinship system 216 Principal terms used 216 Morgan's System -

BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans

U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans BRIEFING REPORT U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS Washington, DC 20425 Official Business DECEMBER 2018 Penalty for Private Use $300 Visit us on the Web: www.usccr.gov U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS MEMBERS OF THE COMMISSION The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is an independent, Catherine E. Lhamon, Chairperson bipartisan agency established by Congress in 1957. It is Patricia Timmons-Goodson, Vice Chairperson directed to: Debo P. Adegbile Gail L. Heriot • Investigate complaints alleging that citizens are Peter N. Kirsanow being deprived of their right to vote by reason of their David Kladney race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national Karen Narasaki origin, or by reason of fraudulent practices. Michael Yaki • Study and collect information relating to discrimination or a denial of equal protection of the laws under the Constitution Mauro Morales, Staff Director because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice. • Appraise federal laws and policies with respect to U.S. Commission on Civil Rights discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws 1331 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or Washington, DC 20425 national origin, or in the administration of justice. (202) 376-8128 voice • Serve as a national clearinghouse for information TTY Relay: 711 in respect to discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, www.usccr.gov religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin. • Submit reports, findings, and recommendations to the President and Congress. -

Creating a Sense of Communityamong the Capital City Cherokees

CREATING A SENSE OF COMMUNITYAMONG THE CAPITAL CITY CHEROKEES by Pamela Parks Tinker A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies Committee: ____________________________________ Director ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Program Director ____________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date:________________________________ Spring 2016 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Creating a Sense Of Community Among Capital City Cherokees A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies at George Mason University By Pamela Parks Tinker Bachelor of Science Medical College of Virginia/Virginia Commonwealth University 1975 Director: Meredith H. Lair, Professor Department of History Spring Semester 2016 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia Copyright 2016 Pamela Parks Tinker All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements Thanks to the Capital City Cherokee Community for allowing me to study the formation of the community and for making time for personal interviews. I am grateful for the guidance offered by my Thesis Committee of three professors. Thesis Committee Chair, Professor Maria Dakake, also served as my advisor over a period of years in planning a course of study that truly has been interdisciplinary. It has been a joyful situation to be admitted to a variety of history, religion and spirituality, folklore, ethnographic writing, and research courses under the umbrella of one Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies program. Much of the inspiration for this thesis occurred at George Mason University in Professor Debra Lattanzi Shutika’s Folklore class on “Sense of Place” in which the world of Ethnography opened up for me. -

Cherokee Genealogy Resource Presentation

FindingFinding youryour CherokeeCherokee AncestorsAncestors ““MyMy GrandmotherGrandmother waswas aa CherokeeCherokee Princess!Princess! ”” WhereWhere toto begin?begin? Information to collect: Names (including maiden names of females) Date and place of birth Date and place of marriage Date and place of death Names of siblings (i.e., brothers and sisters) and Rolls and Roll Numbers SampleSample IndividualIndividual InformationInformation Name:Name: WilliamWilliam CoxCox Born:Born: 77--JuneJune --18941894 inin DelawareDelaware Dist,Dist, CherokeeCherokee NationNation Married:Married: 1515 --OctoberOctober --19191919 inin BlountBlount County,County, TennesseeTennessee toto PollyPolly MorrisMorris Died:Died: 33--AprilApril --19731973 inin Nashville,Nashville, TennesseeTennessee RollRoll // CensusCensus Information:Information: 18961896 CensusCensus // DelawareDelaware DistDist -- RollRoll #517#517 BirthBirth RecordsRecords Oklahoma birth records have been kept since 1925 and are availab le from: Division of Vital Records Oklahoma State Dept. of Health 100 NE 10th Ave PO Box 53551 Oklahoma City, OK 73152 -3551 NOTE: Before 1947, all birth records are filed under the father' s name. After 1947, all birth records are filed under the child's name. Birth Affidavits for Minor Cherokees born (1902 to 1906) were in cluded in the Dawes Applications, and are available from: Oklahoma Historical Society 2401 N Laird Oklahoma City, OK 73105 -4997 Guion Miller Applications also include birthdates and proof of family relationships. These are available -

Challenge Bowl 2020

Notice: study guide will be updated after the December general election. Sponsored by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Challenge Bowl 2020 High School Study Guide Sponsored by the Challenge Bowl 2020 Muscogee (Creek) Nation Table of Contents A Struggle To Survive ................................................................................................................................ 3-4 1. Muscogee History ......................................................................................................... 5-30 2. Muscogee Forced Removal ........................................................................................... 31-50 3. Muscogee Customs & Traditions .................................................................................. 51-62 4. Branches of Government .............................................................................................. 63-76 5. Muscogee Royalty ........................................................................................................ 77-79 6. Muscogee (Creek) Nation Seal ...................................................................................... 80-81 7. Belvin Hill Scholarship .................................................................................................. 82-83 8. Wilbur Chebon Gouge Honors Team ............................................................................. 84-85 9. Chronicles of Oklahoma ............................................................................................... 86-97 10. Legends & Stories ...................................................................................................... -

Chickamauga Names

Chickamaugas / Dragging Canoe Submitted by Nonie Webb CHICKAMAUGAS Associated with Dragging Canoe ARCHIE, John Running Water Town – trader in 1777. BADGER “Occunna” Said to be Attakullakullas son. BENGE, Bob “Bench” b. 1760 Overhills. D. 1794 Virginia. Son of John Benge. Said to be Old Tassels nephew. Worked with Shawnees, and Dragging Canoe. BENGE, John Father of Bob Benge. White trader. Friend of Dragging Canoe. BENGE, Lucy 1776-1848 Wife of George Lowry. BIG FELLOW Worked with John Watts ca. 1792. BIG FOOL One of the head men of Chicamauga Town. BLACK FOX “Enola” Principal Headman of Cherokee Nation in 1819. Nephew to Dragging Canoe. BLOODY FELLOW “Nentooyah” Worked with Dragging Canoe BOB Slave Owner part of Chicamaugas. (Friend of Istillicha and Cat) BOOT “Chulcoah” Chickamauga. BOWL “Bold Hunter” or “Duwali” Running Water Town. b. 1756l- Red hair – blue eyes. Father was Scott. Mother was Cherokee.1768 d, Texas. (3 wives) Jennie, Oolootsa, & Ootiya. Headman Chickamaugas. BREATH “Untita” or Long Winded. Headman of Nickajack Town. d. Ore’s raid in 1794. 1 Chickamaugas / Dragging Canoe Submitted by Nonie Webb BROOM. (see Renatus Hicks) BROWN, James Killed by Chickamaugas on [Murder of Brown Family]….Tennessee River in 1788. Wife captured. Some of Sons and Son in Laws Killed. Joseph Brown captured. Later Joseph led Ore’s raid on Nickajack & Running Water Town in 1794. (Brown family from Pendleton District, S. C.) BROWN, Thomas Recruited Tories to join Chickamaugas. Friend of John McDonald. CAMERON, Alexander. “Scotchee” Dragging Canoe adopted him as his “brother”. Organized band of Torries to Work with the Chicamaugas. CAMPBELL, Alexander. -

The Life and Work of Sophia Sawyer, 19Th Century Missionary and Teacher Among the Cherokees Teri L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 "Behold Me and This Great Babylon I Have Built": The Life and Work of Sophia Sawyer, 19th Century Missionary and Teacher Among the Cherokees Teri L. Castelow Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION "BEHOLD ME AND THIS GREAT BABYLON I HAVE BUILT": THE LIFE AND WORK OF SOPHIA SAWYER, 19TH CENTURY MISSIONARY AND TEACHER AMONG THE CHEROKEES By TERI L. CASTELOW A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Teri L. Castelow defended on August 12, 2004. ______________________________ Victoria Maria MacDonald Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Elna Green Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Sande Milton Committee Member ______________________________ Emanuel Shargel Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Carolyn Herrington, Chair, Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies ___________________________________ Richard Kunkel, Dean, College of Education The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the assistance of several people for their support over the extended period it took to complete the degree requirements and dissertation for my Doctor of Philosophy degree. I would like to thank the many friends and family who have offered encouragement along the way and who did not criticize me for being a perpetual student. My parents, Paul and Nora Peasley, provided moral support and encouragement, as well as occasional child-care so I could complete research and dissertation chapters. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT of COLUMBIA the CHEROKEE NATION, Plaintiff

Case 1:13-cv-01313-TFH Document 248 Filed 08/30/17 Page 1 of 78 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA THE CHEROKEE NATION, Plaintiff/ Counter Defendant, v. RAYMOND NASH, et al., Defendants/ Counter Claimants/ Cross Claimants, --and-- Civil Action No. 13-01313 (TFH) MARILYN VANN, et al., Intervenor Defendants/ Counter Claimants/ Cross Claimants, --and-- RYAN ZINKE, SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR, AND THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, Counter Claimants/ Cross Defendants. MEMORANDUM OPINION Although it is a grievous axiom of American history that the Cherokee Nation’s narrative is steeped in sorrow as a result of United States governmental policies that marginalized Native American Case 1:13-cv-01313-TFH Document 248 Filed 08/30/17 Page 2 of 78 Indians and removed them from their lands,1 it is, perhaps, lesser known that both nations’ chronicles share the shameful taint of African slavery.2 This lawsuit harkens back a century-and-a-half ago to a treaty entered into between the United States and the Cherokee Nation in the aftermath of the Civil War. In that treaty, the Cherokee Nation promised that “never here-after shall either slavery or involuntary servitude exist in their nation” and “all freedmen who have been liberated by voluntary act of their former owners or by law, as well as all free colored persons who were in the country at the commencement of the rebellion, and are now residents therein, or who may return within six months, and their descendants, shall have all the rights of native Cherokees . -

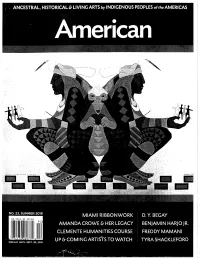

The Clemente Course in the Humanities;' National Endowment for the Humanities, 2014, Web

F1rstAmericanArt ISSUE NO. 23, SUMMER 2019 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Take a Closer Look: 24 Recent Developments 16 Four Emerging Artists By Mariah L. Ashbacher Shine in the Spotlight and America Meredith By RoseMary Diaz ( Cherokee Nation) (Santa Clara Tewa) Seven Directions 20 Amanda Crowe & Her Legacy: 30 By Hallie Winter (Osage Nation) Eastern Band Cherokee Art+ Literature 96 Woodcarving Suzan Shown Harjo By Tammi). Hanawalt, PhD By Matthew Ryan Smith, PhD peepankisaapiikahkia 36 Collections: 100 eehkwaatamenki aacimooni: The Metropolitan Museum of Art A Story of Miami Ribbonwork By Andrea L. Ferber, PhD By Scott M. Shoemaker, PhD Spotlight: Melt: Prayers 104 (Miami), George Ironstrack for the People and the Planet, (Miami), and Karen Baldwin Angela Babby (Oglala Lakota) By Mariah L. Ashbacher Reclaiming Space in Native 44 Calendar 109 Knowledges and Languages By Travis D. Day and America The Clemente Course Meredith (Cherokee Nation) in the Humanities By Laura Marshall Clark (Muscogee Creek) REVIEWS Exhibition Reviews 78 ARTIST PROFILES Book Review 94 D. Y.Begay: 54 Dine Textile Artist By Jennifer McLerran, PhD IN MEMORIAM Benjamin Harjo Jr.: 60 Joe Fafard, OC, SOM (Melis) 106 Absentee Shawnee/Seminole Painter By Gloria Bell, PhD (Metis) and Printmaker Frank LaPefta 107 By Staci Golar (Nomtipom Maidu) By Mariah L. Ashbacher Freddy Mamani Silvestre: 66 Truman Lowe (Ho-Chunk) Aymara Architect By jean Merz-Edwards By Vivian Zavataro, PhD Tyra Shackleford: 72 Chickasaw Textile Artist By Vicki Monks (Chickasaw) COVER Benjamin Harjo 'Jr. (Absentee Shawnee/ Seminole), creator and coyote compete to make man, 2016, gouache on Arches watercolor paper, 20 x 28 in., private collection. -

These Hills, This Trail: Cherokee Outdoor Historical Drama and The

THESE HILLS, THIS TRAIL: CHEROKEE OUTDOOR HISTORICAL DRAMA AND THE POWER OF CHANGE/CHANGE OF POWER by CHARLES ADRON FARRIS III (Under the Direction of Marla Carlson and Jace Weaver) ABSTRACT This dissertation compares the historical development of the Cherokee Historical Association’s (CHA) Unto These Hills (1950) in Cherokee, North Carolina, and the Cherokee Heritage Center’s (CHC) The Trail of Tears (1968) in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Unto These Hills and The Trail of Tears were originally commissioned to commemorate the survivability of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) and the Cherokee Nation (CN) in light of nineteenth- century Euramerican acts of deracination and transculturation. Kermit Hunter, a white southern American playwright, wrote both dramas to attract tourists to the locations of two of America’s greatest events. Hunter’s scripts are littered, however, with misleading historical narratives that tend to indulge Euramerican jingoistic sympathies rather than commemorate the Cherokees’ survivability. It wasn’t until 2006/1995 that the CHA in North Carolina and the CHC in Oklahoma proactively shelved Hunter’s dramas, replacing them with historically “accurate” and culturally sensitive versions. Since the initial shelving of Hunter’s scripts, Unto These Hills and The Trail of Tears have undergone substantial changes, almost on a yearly basis. Artists have worked to correct the romanticized notions of Cherokee-Euramerican history in the dramas, replacing problematic information with more accurate and culturally specific material. Such modification has been and continues to be a tricky endeavor: the process of improvement has triggered mixed reviews from touristic audiences and from within Cherokee communities themselves.