Simplicius:On Aristotle on the Heavens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simplicius and Avicenna on the Nature of Body

Simplicius and Avicenna on the Nature of Body Abraham D. Stone August 18, 1999 1 Introduction Ibn S¯ına, known to the Latin West as Avicenna, was a medieval Aristotelian— one of the greatest of all medieval Aristotelians. He lived in Persia from 980 to 1037, and wrote mostly in Arabic. Simplicius of Cilicia was a sixth cen- tury Neoplatonist; he is known mostly for his commentaries on Aristotle. Both of these men were, broadly speaking, part of the same philosophical tradition: the tradition of Neoplatonic or Neoplatonizing Aristotelianism. There is probably no direct historical connection between them, however, and anyway I will not try to demonstrate one. In this paper I will examine their closely related, but ultimately quite different, accounts of corporeity— of what it is to be a body—and in particular of the essential relationship between corporeity and materiality.1 The problem that both Simplicius and Avicenna face in this respect is as follows. There is a certain genus of substances which forms the subject matter of the science of physics. I will refer to the members of this genus as the physical substances. On the one hand, all and only these physical substances 1A longer and more technical version of this paper will appear, under the title “Simpli- cius and Avicenna on the Essential Corporeity of Material Substance,” in R. Wisnovsky, ed., Aspects of Avicenna (= Princeton Papers: Interdisciplinary Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, vol. 9, no. 2) (Princeton: Markus Wiener, 2000). I want to emphasize at the outset that this paper is about Simplicius and Avicenna, not Aristotle. -

The Fragments of the Poem of Parmenides

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt RESTORING PARMENIDES’ POEM: ESSAYS TOWARD A NEW ARRANGEMENT OF THE FRAGMENTS BASED ON A REASSESSMENT OF THE ORIGINAL SOURCES by Christopher John Kurfess B.A., St. John’s College, 1995 M.A., St. John’s College, 1996 M.A., University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, 2000 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2012 UNVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by Christopher J. Kurfess It was defended on November 8, 2012 and approved by Dr. Andrew M. Miller, Professor, Department of Classics Dr. John Poulakos, Associate Professor, Department of Communication Dr. Mae J. Smethurst, Professor, Department of Classics Dissertation Supervisor: Dr. Edwin D. Floyd, Professor, Department of Classics ii Copyright © by Christopher J. Kurfess 2012 iii RESTORING PARMENIDES’ POEM Christopher J. Kurfess, Ph.D. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 The history of philosophy proper, claimed Hegel, began with the poem of the Presocratic Greek philosopher Parmenides. Today, that poem is extant only in fragmentary form, the various fragments surviving as quotations, translations or paraphrases in the works of better-preserved authors of antiquity. These range from Plato, writing within a century after Parmenides’ death, to the sixth-century C.E. commentator Simplicius of Cilicia, the latest figure known to have had access to the complete poem. Since the Renaissance, students of Parmenides have relied on collections of fragments compiled by classical scholars, and since the turn of the twentieth century, Hermann Diels’ Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, through a number of editions, has remained the standard collection for Presocratic material generally and for the arrangement of Parmenides’ fragments in particular. -

Acknowledgements P. Ix Abbreviations P. X Notes on Contributors P

Acknowledgements p. ix Abbreviations p. x Notes on Contributors p. xvi Introduction p. 1 Early Developments in Reception Introduction: The Old Academy to Cicero p. 10 Speusippus and Xenocrates on the Pursuit and Ends of Philosophy p. 29 The Influence of the Platonic Dialogues on Stoic Ethics from Zeno to Panaetius of Rhodesp. 46 Plato and the Freedom of the New Academy p. 58 Return to Plato and Transition to Middle Platonism in Cicero p. 72 Early Imperial Reception of Plato Introduction: Early Imperial Reception of Plato p. 92 From Fringe Reading to Core Curriculum: Commentary, Introduction and Doctrinal p. 101 Summary Philo of Alexandria p. 115 Plutarch of Chaeronea and the Anonymous Commentator on the Theaetetus p. 130 Theon of Smyrna: Re-thinking Platonic Mathematics in Middle Platonism p. 143 Cupid's Swan from the Academy (De Plat. 1.1, 183): Apuleius' Reception of Plato p. 156 Alcinous' Reception of Plato p. 171 Numenius: Portrait of a Platonicus p. 183 Galen and Middle Platonism: The Case of the Demiurge p. 206 Variations of Receptions of Plato during the Second Sophistic p. 223 Early Christianity and Late Antique Platonism Introduction: Early Christianity and Late Antique Platonism p. 252 Origen to Evagrius p. 271 Sethian Gnostic Appropriations of Plato p. 292 Plotinus and Platonism p. 316 Porphyry p. 336 The Anonymous Commentary on the Parmenides p. 351 Iamblichus, the Commentary Tradition, and the Soul p. 366 Amelius and Theodore of Asine p. 381 Plato's Political Dialogues in the Writings of Julian the Emperor p. 400 Plato's Women Readers p. -

The Cambridge History of Philosophy in Late Antiquity

THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF PHILOSOPHY IN LATE ANTIQUITY The Cambridge History of Philosophy in Late Antiquity comprises over forty specially commissioned essays by experts on the philosophy of the period 200–800 ce. Designed as a successor to The Cambridge History of Later Greek and Early Medieval Philosophy (ed. A. H. Armstrong), it takes into account some forty years of schol- arship since the publication of that volume. The contributors examine philosophy as it entered literature, science and religion, and offer new and extensive assess- ments of philosophers who until recently have been mostly ignored. The volume also includes a complete digest of all philosophical works known to have been written during this period. It will be an invaluable resource for all those interested in this rich and still emerging field. lloyd p. gerson is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Toronto. He is the author of numerous books including Ancient Epistemology (Cambridge, 2009), Aristotle and Other Platonists (2005)andKnowing Persons: A Study in Plato (2004), as well as the editor of The Cambridge Companion to Plotinus (1996). The Cambridge History of Philosophy in Late Antiquity Volume II edited by LLOYD P. GERSON cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 8ru,UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521876421 C Cambridge University Press 2010 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

A Concise History of the Philosophy of Mathematics

A Thumbnail History of the Philosophy of Mathematics "It is beyond a doubt that all our knowledge begins with experience." - Imannuel Kant ( 1724 – 1804 ) ( However naïve realism is no substitute for truth [1] ) [1] " ... concepts have reference to sensible experience, but they are never, in a logical sense, deducible from them. For this reason I have never been able to comprehend the problem of the á priori as posed by Kant", from "The Problem of Space, Ether, and the Field in Physics" ( "Das Raum-, Äether- und Feld-Problem der Physik." ), by Albert Einstein, 1934 - source: "Beyond Geometry: Classic Papers from Riemann to Einstein", Dover Publications, by Peter Pesic, St. John's College, Sante Fe, New Mexico Mathematics does not have a universally accepted definition during any period of its development throughout the history of human thought. However for the last 2,500 years, beginning first with the pre - Hellenic Egyptians and Babylonians, mathematics encompasses possible deductive relationships concerned solely with logical truths derived by accepted philosophic methods of logic which the classical Greek thinkers of antiquity pioneered. Although it is normally associated with formulaic algorithms ( i.e., mechanical methods ), mathematics somehow arises in the human mind by the correspondence of observation and inductive experiential thinking together with its practical predictive powers in interpreting future as well as "seemingly" ephemeral phenomena. Why all of this is true in human progress, no one can answer faithfully. In other words, human experiences and intuitive thinking first suggest to the human mind the abstract symbols for which the economy of human thinking mathematics is well known; but it is those parts of mathematics most disconnected from observation and experience and therefore relying almost wholly upon its internal, self - consistent, deductive logics giving mathematics an independent reified, almost ontological, reality, that mathematics most powerfully interprets the ultimate hidden mysteries of nature. -

The Fragments of the Poem of Parmenides

RESTORING PARMENIDES’ POEM: ESSAYS TOWARD A NEW ARRANGEMENT OF THE FRAGMENTS BASED ON A REASSESSMENT OF THE ORIGINAL SOURCES by Christopher John Kurfess B.A., St. John’s College, 1995 M.A., St. John’s College, 1996 M.A., University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, 2000 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2012 UNVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by Christopher J. Kurfess It was defended on November 8, 2012 and approved by Dr. Andrew M. Miller, Professor, Department of Classics Dr. John Poulakos, Associate Professor, Department of Communication Dr. Mae J. Smethurst, Professor, Department of Classics Dissertation Supervisor: Dr. Edwin D. Floyd, Professor, Department of Classics ii Copyright © by Christopher J. Kurfess 2012 iii RESTORING PARMENIDES’ POEM Christopher J. Kurfess, Ph.D. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 The history of philosophy proper, claimed Hegel, began with the poem of the Presocratic Greek philosopher Parmenides. Today, that poem is extant only in fragmentary form, the various fragments surviving as quotations, translations or paraphrases in the works of better-preserved authors of antiquity. These range from Plato, writing within a century after Parmenides’ death, to the sixth-century C.E. commentator Simplicius of Cilicia, the latest figure known to have had access to the complete poem. Since the Renaissance, students of Parmenides have relied on collections of fragments compiled by classical scholars, and since the turn of the twentieth century, Hermann Diels’ Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, through a number of editions, has remained the standard collection for Presocratic material generally and for the arrangement of Parmenides’ fragments in particular. -

Numbers Their Occult Power and Mystic Virtues

NUMBERS THEIR OCCULT POWER AND MYSTIC VIRTUES by W. Wynn Westcott SUPREME MAGUS OF THE ROSICRUCIAN SOCIETY OF ENGLAND London, Benares: Theosophical Pub. society 3rd Edition [1911] Basilisc Occult Documents/ Occult Specials No. 7 © pdf Benjamin Adamah 2009 www.luxnoxhex.org CONTENTS Preface to the First Edition, 1890 Preface to the Second Edition, 1902 Part I. Pythagoras, his Tenets and his Followers Part II. Pythagorean Views on Numbers Part III. The Kabalah On Numbers Part IV. The Individual Numerals The Monad. 1. The Dyad. 2. The Triad. 3. Three and A Half, 3½ The Tetrad. 4. The Pentad. 5 The Hexad. 6. The Heptad. 7. The Ogdoad. 8. The Ennead. 9. The Decad. 10. Eleven. 11. Twelve. 12. Thirteen. 13. Some Hindoo Uses Of Numbers Other Higher Numbers The Apocalyptic Numbers 1 PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION, 1890. SEVEN years have passed since this essay was written, and the MSS. pages have been lent to many friends and students of mystic lore and occult meanings. It is only at the earnest request of these kindly critics that I have consented to publish this volume. The contents are necessarily of a fragmentary character, and have been collected from an immense number of sources; the original matter has been intentionally reduced to the least possible quantity, so as to obtain space for the inclusion of the utmost amount of ancient, quaint and occult learning. It is impossible to give even an approximate list of works which have been consulted; direct quotations have been acknowledged in numerous instances, and (perhaps naturally) many a statement might have been equally well quoted from the book of a contemporary author, a mediæval monk, a Roman historian, a Greek poet, or a Hindoo Adept: to give the credit to the modern author would not be fair to the ancient sage, to refer the reader to a Sanskrit tome would be in most cases only loss of time and waste of paper. -

On Simplicius' Life and Works: a Response to Hadot

On Simplicius’ Life and Works: A Response to Hadot Pantelis Golitsis Aristotle University of Thessaloniki [email protected] As its title ‘Le néoplatonicien Simplicius à la lumière des recherches contem- poraines. Un bilan critique’ suggests, the book recently published by Ilsetraut Hadot is a critical overview of scholarly research on the Neoplatonist Sim- plicius.1 It focuses on Simplicius’ biography [13–134] and on a selection of his commentaries, namely, his commentaries on Epictetus’ Encheiridion [148–181] and on Aristotle’s On the Soul [182–228], Categories [228–266], and lost works [267–283]. It therefore puts aside Simplicius’ commentaries on Aristotle’s Physics and On the Heavens. No proper explanation is given for this omission but it is reasonable to assume that selection is related here to Ilsetraut Hadot’s own research. Hadot is the first scholar after World War II to engage extensively with Simplicius, providing among several related contributions: (1) a study of his life and works [Hadot 1987a]; (2) the first critical edition of Simplicius’ commentary on Epictetus’ Encheiridion [Hadot 1996]; (By taking into account, in the first study, not only Greek but also Ara- bic sources, Hadot made obsolete Karl Praechter’s entry in the Realenzyk- lopädie [1927], while her contextualized study of the commentary on the Encheiridion (i.e., as an introductory part of the Neoplatonic curriculum) enabled her equally to discard Praechter’s view [1910] that Simplicius, before going to the School of Athens, adhered to an allegedly simplified form of Neoplatonism that was taught at the School of Alexandria.) (3) a sustained defense of the attribution of the commentary on On the Soul to Simplicius [see, most substantially, Hadot 2002], restituted to Simplicius’ fellow philosopher Priscian of Lydia by Ferdinand Bossier and Carlos Steel [1972: cf. -

CANI Annual 2019

MMXIX Promoting the Classics Contents Introduction Qs and Js Back Down the Numismatic Rabbit Hole: The Unknown Caesar Fooling a Forger: 'Pompicus' and the Renegade Deserter The Last Vestal The Original Christian Heretic Classics in Primary Schools (Take Two): Let’s Add Philosophy When Scribes Mess Up: An Ambrosian Doublet in the Muratorian Manuscript The Tombstone of the Unknown Goddess The Thermopylae Gardens at Kilwarlin Moravian Church Crowned in utero - the Youngest Ruler in History? My Favourite Photo of Ancient History III Review of 2019 Book and Movie Reviews Ancient Women Crossword Solutions Introduction I am pleased to present the 2019 CANI annual comprising the best bits of another successful year, as well as classically-themed puzzles. In 2019 CANI offered a wide ranging programme: lectures, a film screening, a public reading of episodes from 5th century BC Greek history, and events for schools. We welcomed speakers from near and far: Professor Michael Scott, Professor Patrick Finglass, Dr Emma Southon, Lynn Gordon and Dr Des O’Rawe. Reviews of all past events can be read on our website. The CANI blog remains active and the highlights are contained here in this volume. Among the historical pieces, you can also read about numismatics, problems with textual transmission, the reception of the ancient world in an unusual garden in County Down, and the promotion of classics in primary schools. CANI prides itself on encouraging interest in classics and ancient history. For some of us, our interest has come later in life, while for others, the Greek and Roman myths are stories that have been with us for a long time. -

Godless Human Philosophy: Truth According to Man

Chapter One Godless Human Philosophy: Truth According to Man “The desire of power in excess caused the angels to fall; the desire of knowledge in excess caused man to fall.” Francis Bacon, Advancement of Learning, 1605 Man’s Futile Search for Wisdom and Truth The origin of the word “philosophy” comes from the combination of the Greek words philos, which means love, and sophia, which means wisdom. The meaning of the word philosophy, therefore, is a “love of wisdom.” As sentient creatures made in the image and likeness of God, human beings have an inborn urge to know and understand the truth. No other creatures have this desire for wisdom and knowledge. That’s what separates us from the brutes. Merely surviving from day to day like the animals do is not enough for mankind, for we cannot live in peace with ourselves if we don’t ponder where we come from and where we’re going when we die. God recognizes this inborn desire we have, for he was the one who gave it to us in the first place, and has revealed himself to us in order that we may know the truth, and love him and seek him out, and ultimately be reunited to him when we die. As we have discovered from the modern sciences of archaeology, anthropology, and paleontology, the whole of human history has been a never-ending search for the truth about our creator. Primitive savages once believed that the heavenly bodies and the natural forces and elements of the earth were gods and therefore worshipped such things as the moon, the sun, the planets, earth, wind, fire, rain, crops, animals, insects, and many other things that exist in the natural realm. -

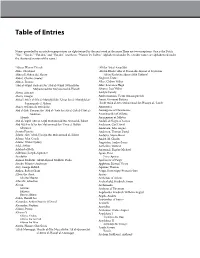

Table of Entries Names Preceded by an Article Or Preposition Are Alphabetized by the Next Word in the Name. There Are Two Excep

Table of Entries Names preceded by an article or preposition are alphabetized by the next word in the name. There are two exceptions: One is the Dutch “Van,” “Van de,” “Van den,” and “Van der.” Another is “Warren De La Rue” (alphabetized under D). (Arabic names are alphabetized under the shortened version of the name.) Abbās Wasīm Efendi Abbe, Cleveland Abbo of Fleury [Abbon de Fleury] Abbot, Charles Greeley Abbott, Francis Abd al-Wājid: Badr al-Dīn Abd al-Wājid [Wāid] ibn Muammad ibn Muammad al-anafī Abetti, Antonio Abetti, Giorgio Abharī: Athīr al-Dīn al-Mufaal ibn Umar ibn al-Mufaal al-Samarqandī al-Abharī Abney, William de Wiveleslie Abū al-Ṣalt: Umayya ibn Abd al-Azīz ibn Abī al-Ṣalt al- Dānī al-Andalusī [Albuzale] Abū al-Uqūl: Abū al-Uqūl Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al-Ṭabarī Abū Mashar Jafar ibn Muḥammad ibn Umar al-Balkhi [Albumasar] Acyuta Piṣāraṭi Ādami: Abū Alī al-Ḥusayn ibn Muḥammad al-Ādami Adams, John Couch Adams, Walter Sydney Adel, Arthur Adelard of Bath Adhémar, Joseph-Alphonse Aeschylus Aḥmad Mukhtār: Ghāzī Aḥmad Mukhtār Pasha Ainslie, Maurice Anderson Airy, George Biddell Aitken, Robert Grant Albert the Great [Albertus Magnus] Albrecht, Sebastian Alcuin [Alchvine; Ealhwine] [Albinus, Flaccus] Alden, Harold Lee Alexander, Arthur Francis O'Donel Alexander, Stephen Alfonsi, Petrus Alfonso X [Alfonso el Sabio, Alfonso the Learned] Alfvén, Hannes Olof Gösta Alī al-Muwaqqit: Muṣliḥ al-Dīn Muṣṭafā ibn Alī 1 al-Qusṭanṭīnī al-Rūmī al-Ḥanafī al-Muwaqqit Alī ibn Īsā al-Asṭurlābī Alī ibn Khalaf: Abū al-asan ibn Amar al-aydalānī [Alī ibn Khalaf ibn Amar Akhīr (Akhiyar)] Alighieri, Dante Allen, Clabon Walter Aller, Lawrence Hugh Alvarez, Luis Walter Amājūr Family Ambartsumian, Victor Amazaspovitch Amici, Giovanni Battista Āmilī: Bahā al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Ḥusayn al-Āmilī Ammonius Anaxagoras of Clazomenae Anaximander of Miletus Anaximenes of Miletus Andalò di Negro of Genoa Anderson, Carl David Anderson, John August Anderson, Thomas David Andoyer, Marie-Henri André, M. -

Table of Entries

Table of Entries Names preceded by an article or preposition are alphabetized by the next word in the name.There are two exceptions: One is the Dutch “Van,” “Van de,” “Van den,” and “Van der.” Another is “Warren De La Rue” (alphabetized under D). (Arabic names are alphabetized under the shortened version of the name.) �Abbās Wasīm Efendi �Alī ibn �īsā al-Asṭurlābī Abbe, Cleveland �Alī ibn Khalaf: Abū al-Ḥasan ibn Aḥmar al-Ṣaydalānī Abbo of [Abbon de] Fleury �Alī ibn Khalaf ibn Aḥmar Akhīr [Akhiyar] Abbot, Charles Greeley Alighieri, Dante Abbott, Francis Allen, Clabon Walter �Abd al-Wājid: Badr al-Dīn �Abd al-Wājid [Wāḥid] ibn Aller, Lawrence Hugh Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Ḥanafī Alvarez, Luis Walter Abetti, Antonio Amājūr Family Abetti, Giorgio Ambartsumian, Victor Amazaspovitch Abharī: Athīr al-Dīn al-Mufaḍḍal ibn �Umar ibn al-Mufaḍḍal al- Amici, Giovanni Battista Samarqandī al-Abharī �Ᾱmilī: Bahā al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Ḥusayn al-�Āmilī Abney, William de Wiveleslie Ammonius Abū al-Ṣalt: Umayya ibn �Abd al-�Azīz ibn Abī al-Ṣalt al-Dānī al- Anaxagoras of Clazomenae Andalusī Anaximander of Miletus Albuzale Anaximenes of Miletus Abū al-�Uqūl: Abū al-�Uqūl Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al-Ṭabarī Andalò di Negro of Genoa Abū Ma�shar Ja�far ibn Muḥammad ibn �Umar al-Balkhi Anderson, Carl David Albumasar Anderson, John August Acyuta Piṣāraṭi Anderson, Thomas David Ādami: Abū �Alī al-Ḥusayn ibn Muḥammad al-Ādami Andoyer, Marie-Henri Adams, John Couch André, M. Charles Adams, Walter Sydney Ångström, Anders Jonas Adel, Arthur Anthelme, Voituret Adelard of Bath