A Social History of Prostitution in Buenos Aires

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guía Para Inspectores De Trabajo Del Mteyss Sobre Detección De Indicios De Explotación Laboral 2020

Guía para inspectores de trabajo del MTEySS sobre detección de indicios de explotación laboral 2020 Dirección Nacional de Fiscalización del Trabajo Guía para inspectores de trabajo del MTEySS sobre detección de indicios de explotación laboral 2020 Guía para inspectores de trabajo del MTEySS sobre detección de indicios de explotación laboral 2020 Material elaborado por la Dirección de Inspección del Trabajo Infantil, Adolescente e Indicios de Explotación Laboral (DITIAEIEL)/DNFT. Bancalari Solá, Marcelo. García, Osvaldo Andrés. Kutscher, Silvia. Pomponio, Marcela. Edita: Dirección de Prensa y Comunicaciones, MTEySS. Septiembre 2020 Autoridades Ministro de Trabajo, Empleo y Seguridad Social de la Nación Dr. Claudio Omar Moroni Secretario de Trabajo Dr. Marcelo Claudio Bellotti Subsecretario de Fiscalización del Trabajo CPN Carlos Alberto Sánchez Director Nacional de Fiscalización del Trabajo CPN Juan María Conte Directora de Inspección del Trabajo Infantil, Adolescente e Indicios de Explotación Laboral Dra. Silvia Graciela Kutscher índice Introducción ....................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Capítulo 1 Breve referencia al marco normativo .................................................................................................11 Capítulo 2 La trata de personas y la explotación ...............................................................................................23 Capítulo 3 Población especialmente -

A Social History of Prostitution in Buenos Aires

chapter 14 A Social History of Prostitution in Buenos Aires Cristiana Schettini Historiography, Methodology, and Sources Established in 1580 as a minor commercial and administrative Spanish settle- ment, the city of Buenos Aires began to experience a certain amount of eco- nomic and political development in the eighteenth century. In the beginning of the nineteenth century, it became the centre for the demand for autonomy from Spain, which was finally obtained in 1816. Its population grew from 14,000 in 1750 to 25,000 in 1780, and to 40,000 by the end of the century. In 1880, after decades of political instability, the city was federalized, thereby concentrating the political power of the Argentine Republic. From then on, massive influxes of Europeans changed the city’s demographics, paving the way for its transfor- mation into a major world port and metropolis with a population of 1,300,000 by 1910 and around 3,000,000 as the twentieth century wore on. The study of prostitution in Buenos Aires has attracted the attention of re- searchers from various fields such as social history and cultural and literary studies, and more recently urban history and the social sciences, especially anthropology. Although the topic has been addressed in its symbolic dimen- sion, much less attention has been devoted to the social organization of the sex trade, its changes, the social profiles of prostitutes, and their relationships with other types of workers and social groups. Similarly, the importance granted to the period of the municipal regulation of prostitution (1875–1936) and to stories about the trafficking of European women stands in stark contrast to the scar- city of studies on the long period since 1936, especially as regards issues aside from public policies implemented to fight venereal diseases. -

A Cien Años Del Cristo Redentor

fí.'<lIS!"¡ Id flll'flllHI.I rlc\( IUII,II Director: Félix Luna A cien años del Cristo Redentor Un cronopio pequeñito buscaba la llave de la puerta de calle en la mesa de luz, la mesa de luz en el dornútorio, el dormitorio en la casa, la casa en la calle. Aquí se detenia el cronopio, pues para salir a la calle precisaba la llave de la puerta. Un clonopio se recibe de médico y abre su consultorio en 1. caUe Santiago del Estero. En seguida vIene un enfermo y le cuenta cómo hay cosas que le duelen y cómo de noche no duerme y de día no come. -Compre un gran ramo de rosas· dice el cronopio. El enfermo se retira sorprendido, pero compra el ramo y se cura instantáneamente. !Jeno de gratltud acude al cronoplo, y además de pagarle le obsequIa, fmo testtmoruo, un hermoso ramo de rosas. Apenas se ha Ido el cronoplo cae enfermo, le duele por mdos lados, de noche no duerme)' de día no come. Julio Cortbar ,¡, J¡HIrma! rlt crfJlltJptOJ.J ti, JIlI1I(JS HIS~@RIA Esta revista ha sIdo declarada Sumario de interés nacional por /a Cá AÑo XXXVI mara de Diputados de /a Na ción (1992) y de interés muni MARZO DE 2004 Nº 440 cipal por el Concejo DelIbe "Historia, émula del tiempo, depósito de las acciones, testigo de lo pasado, rante de /a ciudad de Buenos ejemplo y aviso de lo presente, advertencia de lo por vemr. .. " Aires. CERVANTES, Quijote, 1. IX ---_._--" .:.:.::::::": :::: ......•...•..... CULTOS POPULARES EL ESTADISTAOUE HIZO POSIBLE LA EN LA ARGENTINA LIBERTAD ELECTORAL SIal! EOMUNDO JORGE DELGADO - JORGE R. -

Espacios De Género

ADLAF C ONGRESO A NU A L 2012 La Fundación Friedrich Ebert (en La Asociación Alemana de alemán: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, fes) Investigación sobre América Latina fue creada en 1925 como legado (Adlaf, por sus siglas en alemán), político de Friedrich Ebert, fue fundada en 1965 y es una socialdemócrata y primer presidente En las últimas décadas, América Latina pasó agrupación interdisciplinaria alemán elegido democráticamente. compuesta por institutos El Departamento de Cooperación por diversos procesos de modernización de investigación e investigadoras Internacional para el Desarrollo de social que impactaron en las relaciones de género, Espacios e investigadores en diferentes la fes fomenta el desarrollo especialidades enfocados al estudio sostenible y la democracia en ampliaron la representación de las mujeres de América Latina. La Adlaf está América Latina, Asia, África y el integrada actualmente por más y cambiaron las construcciones del cuerpo, Oriente Próximo. Junto con sus de género de 25 institutos y más de 200 socios, actores de la política social la sexualidad y las identidades sexuales. investigadoras e investigadores y de más de 100 países, el su propósito, de acuerdo con sus departamento contribuye a: Los nuevos «espacios de género», sus conflictos y estatutos, es llevar a cabo las • asegurar estructuras democráticas potencialidades fueron debatidos en la Conferencia siguientes tareas: poner a mediante la inclusión del disposición de sus miembros y de conjunto más numeroso posible de la Asociación Alemana de Investigación otros círculos interesados en la de grupos sociales; sobre América Latina (Adlaf) que convocó a más región, fuentes de información y • fomentar procesos de reforma y materiales localizados en diversas mecanismos para una conciliación no de 130 personalidades latinoamericanas y partes de Alemania; promover la conflictiva de intereses divergentes; investigación, la enseñanza y las europeas de los ámbitos académico, político y cultural • elaborar en conjunto estrategias publicaciones sobre América Latina globales para el futuro. -

Read Book Born to Kill : the Rise and Fall of Americas Bloodiest

BORN TO KILL : THE RISE AND FALL OF AMERICAS BLOODIEST ASIAN GANG PDF, EPUB, EBOOK T J English | 310 pages | 09 Jun 2009 | William Morrow & Company | 9780061782381 | English | New York, NY, United States Born to Kill : The Rise and Fall of Americas Bloodiest Asian Gang PDF Book My library Help Advanced Book Search. Upping the ante on depravity, their specialty was execution by dismemberment. English The Westies, follows the life and criminal career of Tinh Ngo, a No trivia or quizzes yet. True crime has been enjoying something A must for anyone interested in the emerging multiethnic face of organized crime in the United States. June 16, This was a really great read considering it covers a part of Vietnamese American culture that I had never encountered or even heard of before. As he did in his acclaimed true crime masterwork, The Westies , HC: William Morrow. English The Westies, follows the life and criminal career of Tinh Ngo, a How cheaply he could buy loyalty and affection. As of Oct. Headquartered in Prince Frederick, MD, Recorded Books was founded in as an alternative to traditional radio programming. They are children of the Vietnam War. Reach Us on Instagram. English William Morrow , - Seiten 1 Rezension Throughout the late '80s and early '90s, a gang of young Vietnamese refugees cut a bloody swath through America's Asian underworld. In America, these boys were thrown into schools at a level commensurate with their age, not their educational abilities. The only book on the market that follows a Vietnamese gang in America. Exclusive Bestsellers. -

~Emernbering Sepharad

RE YE S C O LL-TELLECHEA ~e mernbering Sepharad Accompanying Christopher Columbus on board the Sal/ta Marfa as it left the Iberia n Pe ni ns ula on August 3,1492, was Luis de Torres. De Torres, a polyglot , was the expedition's inkrpreter. Like many other Iberian JeWS , de Torres had recently converted to Christianity in an attempt to preserve his right to live in Sepharad, the land Iberian Jevvs had inhabited for twelve hundred years. The Edict of Expulsion, dated March 31, 1492, deprived Jews of all their rights and gave them three months to put their affairs in order and go in to exile. Implicit in the edict was exemption if jews con verted to Ch ristianity. It was only implicit, of courSe, becaLlse neither the laws of th e land nor the laws of the Catholic church provided for forced conversion. Although conversos would be granted full rights of citizen ship, the Inquisition, in turn, had the right to investigate and persecute the "new" Ch rist ians in order to prevent deviations from church doctrine. Those who did not accept conversion would be expelled from the land forever. The fate of Sepharad was irreversible. Now We can only remember Sepharad. Remembrance cannOt restore that which has been lost, but it is essen tiul to recognize the limitless power of human action to create as well as to destroy. Memory is not a maner of the past but a fundamental tool for analyzin g the prese nt and marching into the future with knowledge and conscience. -

“'Like a Helpless Animal"? Like a Cautious Woman: Joyce's 'Eveline,' Immigration, and the Zwi Migdal in Argentina

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Bronx Community College 2011 “‘Like a Helpless Animal"? Like a Cautious Woman: Joyce’s ‘Eveline,’ Immigration, and the Zwi Migdal in Argentina in the Early 1900s M Laura Barberan Reinares CUNY Bronx Community College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/bx_pubs/8 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] NOTES Like a “Helpless Animal” (D 41)? Like a Cautious Woman: Joyce’s “Eveline,” Immigration, and the Zwi Migdal in Argentina in the Early 1900s Laura Barberan Reinares Bronx Community College of the City University of New York n his 1972 essay “Molly’s Masterstroke,” Hugh Kenner challenges Ithe “conventional and superficial” readings of “Eveline” that suggest this (anti)heroine remains paralyzed in the end, unable to embrace a promising future with Frank in Buenos Aires.1 Katherine Mullin, for her part, presents compelling evidence on the discourses of white-slave trafficking circulating in Europe around the time Joyce was writing and revising “Eveline” for publication.2 In this note, I will provide further key facts supporting Kenner’s and Mullin’s read- ing of the story, since a historical look at the circumstances of Frank’s tales further reinforces questions about the sailor’s honesty. “Eveline” was first published in The Irish Homestead on 10 September 1904. One month later, on 8 October, Joyce moved to Pola for a brief period and later to Trieste, where he began his permanent exile. -

White Slavery and Jews

1 White Slavery and Jews White Slave by Mary Abastenia St. Leger Eberle -1913 In memory of Sophia Chamys By Jerry Klinger Anti-Semitism’s heel ground harder, unrelenting, crushing, murderous and vicious. Jewish life, the worth of Jewish life, in Poland and Russia, plunged into degeneration. Zionism, Max Nordau knew, was the path to regeneration.” Judith Rice "Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion] could not imagine that Jewish women would stoop to crime or prostitution. Meyer Weisgal, a close associate, who resembled David Ben-Gurion, humorously quipped, a girl walked up to him on a London street and offered her services, overwhelmed by the idea of sleeping with the 'Israeli prime minister.' Ben-Gurion, clearly troubled, was interested in only one thing: 'Was she Jewish?” 2 “What is worse… ten times worse… no a hundred times worse? If sexual immorality becomes accepted, the strong will exploit the weak… God will send a new flood. It will be his tears, raining from the sky. Rabbi Zusia Friedberg – Baltimore, Md. 1895 My mother told me about him. Salomon Gomberg was a hero. The Nazis did not think of him that way. The Jews did. In the winter of 1943, the Nazis ordered him to come to Gestapo headquarters in Pietrokow Trybunalski. He stood at attention outside the building. They removed his overcoat, his shoes. The biting cold snow and sleet whirled in mini-cyclones. The Nazis poured buckets of ice water over his clothes, soaking them. Quickly the wet clothing turned to ice. He stood outside the Gestapo headquarters the entire night, shivering violently. -

The Other/Argentina

The Other/Argentina Item Type Book Authors Kaminsky, Amy K. DOI 10.1353/book.83162 Publisher SUNY Press Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 29/09/2021 01:11:31 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://www.sunypress.edu/p-7058-the-otherargentina.aspx THE OTHER/ARGENTINA SUNY series in Latin American and Iberian Thought and Culture —————— Rosemary G. Feal, editor Jorge J. E. Gracia, founding editor THE OTHER/ARGENTINA Jews, Gender, and Sexuality in the Making of a Modern Nation AMY K. KAMINSKY Cover image: Archeology of a Journey, 2018. © Mirta Kupferminc. Used with permission. Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2021 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY www.sunypress.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kaminsky, Amy K., author. Title: The other/Argentina : Jews, gender, and sexuality in the making of a modern nation / Amy K. Kaminsky. Other titles: Jews, gender, and sexuality in the making of a modern nation Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, [2021] | Series: SUNY series in Latin American and Iberian thought and culture | Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Human Trafficking

HUMAN TRAFFICKING: A Comparative Analysis of Why Countries with Similar Characteristics have Different Situations By Ana R. Sverdlick A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program, Division of Global Affairs Written under the direction of Professor James O. Finckenauer and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ Newark, New Jersey January 2014 © 2013 Ana R. Sverdlick ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT HUMAN TRAFFICKING: A Comparative Analysis of Why Countries with Similar Characteristics have Different Situations By Ana R. Sverdlick Dissertation Director: Professor James O. Finckenauer Numerous factors which promote human trafficking have been examined by many scholars, yet little attention has been placed on the role of adolescent single mothers as a significant factor that increases the vulnerability of these young women to trafficking. This study aims to understand and explain why two countries with similar characteristics in geography, political and socio-economic systems present a very different picture in their sex trafficking patterns and challenges. This is a case study that compares Argentina and Brazil along a variety of indicators relevant to human trafficking. Although similar with respect to several characteristics analyzed in their incidence of sex trafficking, Argentina and Brazil do differ in one major factor that on its face could account for the differences in their sex trafficking practices --birth rate among adolescent girls aged 15 to 19. This rate is higher in Brazil than that in Argentina. This study seeks to answer the following questions: 1. -

See Pseudo-Subject Age Female Criminality Based On, 209 Of

Index Administrators, women as, 65 illegal associations vs. mafia state, 159–160 Affirmation of feminine pseudo-subject: see immigration and criminal organizations, Pseudo-subject 161–162 Age internal feuds, 155–156 female criminality based on, 209 the repressive machine, 160–161 of mafia women, 76, 123, 125, 142 women who exercise direct power, 164–165 Agnello, Carmine, 252–253 women who exercise power indirectly, Al Kassar, Monzer, 159, 167 165–166 Albania, 297–298 Arlete “China da Saude,” 194 characteristics of women involved in criminal Arms trafficking, 166–169 activities, 141–145 Arrests of men vs. women, 105, 208 crimes committed by women, 140–141 “Astuteness of female impotence,” 33, 42–43 Albanian legislation, evolution of, 139–140 Ayerza, Ariel, 152, 153, 155 Andrade, Castor de, 195 Anego, 211, 293 Bankers, 193–195; see also Bicheiros Animal Game Bankers, 299–300; see also Jogo Beatriz, Amira: see Yoma, Amira dos bichos Behavioral typologies, 76 “Anna Morte” (“Anna Death”), 63–64 associative, 2–3 Anzai, Chizue, 213 extra-associative, 3–5 Appeso, Massimo, 63 Belay, Fitore, 297–298 Argentina, 149–150, 294–297 Bergasi, Jorida, 145–146n.1 female criminality in, 162–174 Berman, Susan, 251, 262 types of crimes committed, 163–164 Bicheiros, 184–185, 193–195, 300, 301 women in prison, 163 Biondi, Domenica “Mimina,” 59–61 Yoma sisters, 166–169 Black Hand extortion rings, 242 mafia in Bluevstein, Sofia Ivanovna, 232 Agata Galifii, 153–154, 295 Boemi, Savatore, 27, 28, 30–31, 33–35 “Chicho Grande” and “Chicho Chico,” B¨ogel, Marion, 222 152–154 -

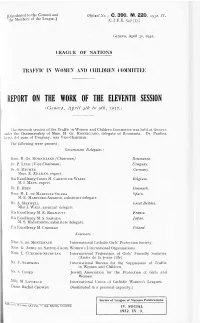

REPORT on the WORK of the ELEVENTH SESSION ( G En Eva , a P R I L J T H to 9 Th , 1932.)

[Distributed to the Council and Official No. ; C. 390. M. 220. 1032. IV. the Members of the League.] [C.T.F.E. 547 (i)-l Geneva, April 30, 1932. LEAGUE OF NATIONS TRAFFIC IN WOMEN AND CHILDREN COMMITTEE REPORT ON THE WORK OF THE ELEVENTH SESSION ( G en eva , A p r i l j t h to 9 th , 1932.) The eleventh session of the Traffic in Women and Children Committee was held at Geneva under the Chairmanship of Mme. H. Gr. Romniciano, delegate of Roumania. Dr. Paulina L u isi, delegate of Uruguay, was Vice-Chairman. The following were present : Government Delegates : Mme. H. Gr. R om niciano (Chairman) Roumania. Dr. P. L uisi (Vice-Chairman) Uruguay. Dr. G. BAum er Germany. Mme. E. Zil l k e n , expert. His Excellency Count H. Carton d e W iart Belgium. M. I. M a u s , expert. Dr. E. H ein Denmark. Mme. M. L. de M artinez S ier ra Spain. M. E. Ma r tin e z-A m a d o r , substitute delegate. Mr. A. Ma x w e l l Great Britain. Miss I. W a l l , assistant delegate. His Excellency M. E. R eg n a u l t France. His Excellency M. S. S a w a d a Japan. M. S. Matsum o to , substitute delegate. His E xcellency M. Chodzko Poland. Assessors : Mme. S. d e Mo nten a c h International Catholic Girls’ Protection Society. Mme. G. A vril d e Sa in t e -C roix Women’s International Organisations.