Interview Rem Koolhaas and Reinier De Graaf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Lille-Flandres to Lille-Europe —The Evolution of a Railway Station Corinne Tiry

Feature From Lille-Flandres to Lille-Europe From Lille-Flandres to Lille-Europe —The Evolution of a Railway Station Corinne Tiry Since the mid-19th century, European Council, the Northern Railway Company economic arguments finally prevailed and cities evolved around the railway station established in 1845 by the Rothschild a good compromise was adopted—two as a central pivot where goods and people family, the French government and some stations would be built, a terminal inside converge. This is still true today when of Lille's most prominent citizens. These the city walls for passengers traffic, and a railway stations take on a new role as controversies also stimulated nearby urban through terminal outside for goods traffic. urban hubs in the European high-speed projects. Construction of the passenger terminal train network. Lille in northern France, started in 1845, and lasted 3 years. which has two stations from different The Railway Station Enters However, the builders underestimated the railway periods—Lille-Flandres and Lille- the City scale of both passenger and freight traffic Europe, is a good example illustrating this and the capacity was soon saturated. To quasi-continuous past and present urban In the 19th century, the railway station solve this new problem, an Imperial ambitions. became a new gateway to the city, Decree in 1861 allowed the Northern Lille is a city of 170,000 adjacent to the disrupting both the city walls' protective Railway Company to start construction of French-Belgian border. It is at the economic function, as well as the urban layout. The a marshalling yard—called Saint-Sauveur heart of the Lille-Roubaix-Tourcoing- original controversy in Lille emerged from station—south of the main passenger Villeneuve d'Ascq conurbation of 1.2 this duality and a station inside the city station, at the junction of the old city and million people, ranking (excepting Paris) was strongly opposed by the military. -

Cladmag 2018 Issue 2

2018 ISSUE 2 CLADGLOBAL.COM mag @CLADGLOBAL FOR LEISURE ARCHITECTS, DESIGNERS, INVESTORS & DEVELOPERS INSIGHT PROFILE PERKINS+WILL’S DAVID Gabrielle COLLINS Bullock The good news STUDIO on diversity Keeping the legacy of its Martha founder alive Schwartz I became known for being controversial In my work, form follows fiction Ole Scheeren CREATORS OF WELLBEING AND RELAXATION Interior Design I Engineering Design IWŽŽůнdŚĞƌŵĂů/ŶƐƚĂůůĂƟŽŶI Maintenance Middle East + Asia UK + Europe ƐŝĂWĂĐŝĮĐ Barr + Wray Dubai Barr + Wray Barr + Wray Hong Kong T: + 971 4320 6440 T: + 44 141 882 9991 T: + 852 2214 9990 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] E: [email protected] www.barrandwray.com HEATED MARBLE LOUNGE CHAIRS By Fabio Alemanno Developed for the spa Perfected for the suite An exceptional collection of Regenerative warmth will pamper you whether handcrafted marble sculptures for in the Spa, the intimacy of the Suite or the Living room, making your rest unforgettable. hotel, spa and residential design With proven therapeutical benefits of long- Cut from a single block of flawless marble, wave infrared and advanced technical maturity, Fabio Alemanno infra-red heated lounge our products have become the first choice chairs are ergonomically shaped and for discerning clients around the world. unique in their design and structure. Unlimited choices of marble, exotic wood, leather, They combine wellness with design and technology and fabrics enable a perfect and seamless integration offering unparalleled comfort and amazing relaxation into any environment, offering architects and interior experiences while enhancing the state of well-being. designers endless possibilities for customisation. [email protected] www.fa-design.co.uk EDITOR’S LETTER Tree planting is one of the only ways to save the planet from #earthdeath Reforesting the world Climate scientists believe carbon capture through tree planting can buy us time to transition away from fossil fuels without wrecking the world’s economy. -

Building for Wellness: the Business Case

Building for Wellness THE BUSINESS CASE Building Healthy Places Initiative Building Healthy Places Initiative ULI Center for Capital Markets and Real Estate BuildingforWellness2014cover.indd 3 3/18/14 2:13 PM Building for Wellness THE BUSINESS CASE Project Director and Author Anita Kramer Primary Author Terry Lassar Contributing Authors Mark Federman Sara Hammerschmidt This project was made possible in part through the generous financial support of ULI Foundation Governor Bruce Johnson. ULI also wishes to acknowledge the Colorado Health Foundation for its support of the ULI Building Healthy Places Initiative. Building Healthy ULI Center for Capital Markets Places Initiative and Real Estate ACRONYMS HEPA—high-efficiency particulate absorption HOA—homeowners association Recommended bibliographic listing: HUD—U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Kramer, Anita, Terry Lassar, Mark Federman, and Sara Hammer- HVAC—heating, ventilation, and air conditioning schmidt. Building for Wellness: The Business Case. Washington, D.C.: LEED—Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design Urban Land Institute, 2014. VOC—volatile organic compound ISBN: 978-0-87420-334-9 MEASUREMENTS © 2014 Urban Land Institute 1025 Thomas Jefferson Street, NW ac—acre Suite 500 West ha—hectare Washington, DC 20007-5201 km—kilometer All rights reserved. Reproduction or use of the whole or any part of mi—mile the contents without written permission of the copyright holder is sq ft—square foot prohibited. sq m—square meter 2 BUILDING FOR WELLNESS: THE BUSINESS CASE About the Urban Land Institute The mission of the Urban Land Institute is to provide • Sustaining a diverse global network of local prac- leadership in the responsible use of land and in tice and advisory efforts that address current and creating and sustaining thriving communities world- future challenges. -

Rem Koolhaas: an Architecture of Innovation Daniel Fox

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Volume 16 - 2008 Lehigh Review 2008 Rem Koolhaas: An Architecture of Innovation Daniel Fox Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/cas-lehighreview-vol-16 Recommended Citation Fox, Daniel, "Rem Koolhaas: An Architecture of Innovation" (2008). Volume 16 - 2008. Paper 8. http://preserve.lehigh.edu/cas-lehighreview-vol-16/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Lehigh Review at Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 16 - 2008 by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rem Koolhaas: An Architecture of Innovation by Daniel Fox 22 he three Master Builders (as author Peter Blake refers to them) – Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Frank Lloyd Wright – each Drown Hall (1908) had a considerable impact on the architec- In 1918, a severe outbreak ture of the twentieth century. These men of Spanish Influenza caused T Drown Hall to be taken over demonstrated innovation, adherence distinct effect on the human condi- by the army (they had been to principle, and a great respect for tion. It is Koolhaas’ focus on layering using Lehigh’s labs for architecture in their own distinc- programmatic elements that leads research during WWI) and tive ways. Although many other an environment of interaction (with turned into a hospital for Le- architects did indeed make a splash other individuals, the architecture, high students after St. Luke’s during the past one hundred years, and the exterior environment) which became overcrowded. Four the Master Builders not only had a transcends the eclectic creations students died while battling great impact on the architecture of of a man who seems to have been the century but also on the archi- influenced by each of the Master the flu in Drown. -

Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas

5 Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas has been part of the international avant-garde since the nineteen-seventies and has been named the Pritzker Rem Koolhaas Architecture Prize for the year 2000. This book, which builds on six canonical projects, traces the discursive practice analyse behind the design methods used by Koolhaas and his office + OMA. It uncovers recurring key themes—such as wall, void, tur montage, trajectory, infrastructure, and shape—that have tek structured this design discourse over the span of Koolhaas’s Essays on the History of Ideas oeuvre. The book moves beyond the six core pieces, as well: It explores how these identified thematic design principles archi manifest in other works by Koolhaas as both practical re- Ingrid Böck applications and further elaborations. In addition to Koolhaas’s individual genius, these textual and material layers are accounted for shaping the very context of his work’s relevance. By comparing the design principles with relevant concepts from the architectural Zeitgeist in which OMA has operated, the study moves beyond its specific subject—Rem Koolhaas—and provides novel insight into the broader history of architectural ideas. Ingrid Böck is a researcher at the Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies at the Graz Ingrid Böck University of Technology, Austria. “Despite the prominence and notoriety of Rem Koolhaas … there is not a single piece of scholarly writing coming close to the … length, to the intensity, or to the methodological rigor found in the manuscript -

Uma Arqueologia Do Programa De Rem Koolhaas Adriana Veras Vasconcelos, Doutoranda Pelo MDU-UFPE E Upenn, Professora Assistente Do Depto

Simpósio Temático: Da arte de construir à inteligência arquitetônica Megaestructura e Metrópole: Uma arqueologia do programa de Rem Koolhaas Adriana Veras Vasconcelos, Doutoranda pelo MDU-UFPE e UPenn, Professora Assistente do Depto. de Arquitetura da UFPB Fernando Diniz Moreira, Ph.D., Professor Adjunto do Depto. de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da UFPE 1 Resumo Termos como fragmentação, heterogeneidade, descontinuidade e imaterialidade têm sido constantemente usados para descrever a metrópole contemporânea. A tecnologia da informação e a justaposição de fluxos e realidades parecem enfraquecer uma tradição arquitetônica consolidada, baseada na tríade venustas, commoditas e utilitas. No entanto, estas mesmas características podem também estimular uma nova forma de pensar e fazer arquitetura. Nesse contexto, Rem Koolhaas é um dos arquitetos que mais tem explorado a metrópole como estratégia projetual, expondo a instabilidade da condição urbana atual. Originalmente jornalista e cineasta, Koolhaas publicou Delirious New York, um dos mais importantes manifestos da arquitetura contemporânea. Ele aceita a submissão da arquitetura à aparente falta ordem, fragmentação e heterogeneidade da metrópole contemporânea. Segundo ele, a metrópole é estruturada pela concentração e superposição de vários sistemas urbanos. Sua dinâmica é mantida pela congestão de atividades, espaços e programas que devem ser articulados por bigness: mecanismo arquitetônico capaz de sustentar uma proliferação de eventos em um único edifício. Para Koolhaas, a tarefa da arquitetura não é mais organizar o espaço com elementos permanentes, mas expor o caos da cidade no próprio edifício. O objetivo deste trabalho é oferecer uma arqueologia da obra de Koolhaas, estabelecendo conexões entre o pensamento arquitetônico e urbanístico das décadas de 1960 e 1970 suas idéias e entre estas e seus projetos construídos. -

OMA at Moma : Rem Koolhaas and the Place of Public Architecture

O.M.A. at MoMA : Rem Koolhaas and the place of public architecture : November 3, 1994-January 31, 1995, the Museum of Modern Art, New York Author Koolhaas, Rem Date 1994 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/440 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art THRESHOLDS IN CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE O.M.A.at MoMA REMKOOLHAAS ANDTHE PLACEOF PUBLICARCHITECTURE NOVEMBER3, 1994- JANUARY31, 1995 THEMUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK THIS EXHIBITION IS MADE POSSIBLE BY GRANTS FROM THE NETHERLANDS MINISTRY OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS, LILY AUCHINCLOSS, MRS. ARNOLD L. VAN AMERINGEN, THE GRAHAM FOUNDATION FOR ADVANCED STUDIES IN THE FINE ARTS, EURALILLE, THE CONTEMPORARY ARTS COUNCIL OF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, THE NEW YORK STATE COUNCIL ON THE ARTS, AND KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES. REM KOOLHAASAND THE PLACEOF PUBLIC ARCHITECTURE ¥ -iofiA I. The Office for Metropolitan Architecture (O.M.A.), presence is a source of exhilaration; the density it founded by Rem Koolhaas with Elia and Zoe engenders, a potential to be exploited. In his Zenghelis and Madelon Vriesendorp, has for two "retroactive manifesto" for Manhattan, Delirious decades pursued a vision energized by the relation New York, Koolhaas writes: "Through the simulta ship between architecture and the contemporary neous explosion of human density and an invasion city. In addition to the ambitious program implicit in of new technologies, Manhattan became, from the studio's formation, there was and is a distinct 1850, a mythical laboratory for the invention and mission in O.M.A./Koolhaas's advocacy of the city testing of a revolutionary lifestyle: the Culture of as a legitimate and positive expression of contem Congestion." porary culture. -

Kris Provoost Belgium/China [email protected] - +8618616388046 Raffles City, Hangzhou

Photography Portfolio 2018 Architecture + Infrastructure Kris Provoost Belgium/China [email protected] - +8618616388046 Raffles City, Hangzhou Commission: UNStudio August 2018 Exterior and Aerial Photography Pudong Museum of Art, Shanghai Architect: Atelier Deshaus May 2018 Exterior Photography Gubei SOHO, Shanghai Architect: KPF May 2018 Construction Photography Harbin Grand Theater, Harbin Commision: MAD Architects July 2017 Exterior, Interior and Aerial Photography A11 Bridge, Bruges, Belgium Commission: Schlaich Bergermann Partner December 2017 Exterior Photography West Bund Bridge Zhangjiatang Commission: Schlaich Bergermann Partner September 2017 Construction and Aerial Photography Abu Dhabi Louvre Architect: Jean Nouvel December 2017 Exterior and Interior Photography Tianjin Binhai Library, Tianjin Commision: MVRDV December 2017 Exterior and Interior Photography TSMC Fab, Nanjing Commision: Kris Yao Artech July 2018 Exterior, Interior, Aerial Photography Beautified China Photo-essay capturing China flamboyant building boom DUO, Singapore Architect: Buro Ole Scheeren October 2017 Abstract Photography Kris Provoost: Publications: Kris Provoost is a Belgian born architect and photographer. Online Photography Portfolio: Kris’ work has been published around the world online and in Beautified China, photo-essay by Kris Provoost He is active in Asia designing and capturing buildings and https://www.krisprovoost.com print media. His Beautified China series is well received and has cities, to better understand the build environment. appeared on CNN, FastCoDesign, Fubiz, Abduzeedo, ArchDaily, Dezeen - April 30th, 2017 Online Videography Portfolio: Dezeen, Designboom, gooood, New York Times Magazine Kris Provoost photographs the most flamboyant architecture of https://www.youtube.com/donotsettle Spain, as well as in print magazines China Life, ArchiKultura, China’s building boom After graduating in 2010 with a Master in Architecture, he Experimenta, That’s Mag and others. -

Büro Ole Scheeren Unveils Design for Guardian Art Center in Beijing

PRESS RELEASE March 9, 2015 A fusion of time and a synthesis of China's rich cultural history: Büro Ole Scheeren unveils design for Guardian Art Center in Beijing Located in close proximity to the Forbidden City, construction is underway on the new headquarters of China’s oldest art auction house. Embedded in the historic fabric of central Beijing, the building will form a new hybrid institution between museum, event space, and cultural lifestyle center. Ole Scheeren’s design for the Guardian Art Center carefully inscribes the building into the surrounding context, in a sensitive architectural interpretation that fuses history and tradition with a contemporary vision for the future of a cultural art space. The ‘pixelated’ volumes of the lower portion of the building subtly refer to the adjacent historic urban fabric, echoing the grain, color and intricate scale of Beijing’s hutongs, while the upper portion of the building responds to the larger scale of the surrounding contemporary city. This floating ‘ring’ forms an inner courtyard to the building and further resonates with the prevalent typology of the courtyard houses in Beijing. “The Art Center will be a tangible link between past, present, and future. It celebrates history and tradition while also representing an important social and civic amenity for the capital” says China Guardian’s Chairman and Founder, Chen Dongsheng. “The design of the building shares its qualities with those of Guardian. It is profound, simple, and clean, and exudes a sense of stability and trustworthiness” adds Mr. Chen. “Ole Scheeren’s work is rooted in culture and history; it reflects the culture of the site and the culture and customs of the Chinese people. -

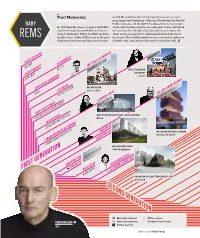

First Generation Second Generation

by Paul Makovsky world. Not only has the firm designed some of our era’s most important buildings—Maison à Bordeaux, the Seattle BABY Public Library, and the CCTV headquarters, to name just In 1975 Rem Koolhaas, together with Elia a few—but its famous hothouse atmosphere has cultivated and Zoe Zenghelis and Madelon VriesenVriesen-- the talents of hundreds of gifted architects. Look at the dorp, founded the Office for Metropolitan chart on these pages: it is a distinguished architectural REMS Architecture. Today OMA is one of the most fraternity. These OMA grads have now created an influence influential architectural practices in the all their own, and they are the ones to watch in 2011. P ZAHA HADID RIENTS DIJKSTRA EDZO BINDELS MAXWAN MATTHIAS SAUERBRUCH WEST 8 SAUERBRUCH HUTTON EVELYN GRACE ACADEMY CHRISTIAN RAPP London RAPP + RAPP CHRISTOPHE CORNUBERT M9 MUSEUM LUC REUSE Venice, Italy WILLEM JAN NEUTELINGS PUSH EVR ARCHITECTEN NEUTELINGS RIEDIJK LAURINDA SPEAR ARQUITECTONICA KEES CHRISTIAANSE SOUTH DADE CULTURAL ARTS CENTER KGAP ARCHITECTS AND PLANNERS Miami YUSHI UEHARA ZERODEGREE ARCHITECTURE MVRDV WINY MAAS MUSEUM AAN DE STROOM Antwerp, Belgium RUURD ROORDA KLAAS KINGMA JACOB VAN RIJS KINGMA ROORDA ARCHITECTEN BALANCING BARN Suffolk, England FOA WW ARCHITECTURE SARAH WHITING FARSHID MOUSSAVI RON WITTE FIRST GENERATION MIKE GUYER ALEJANDRO ZAERA POLO GIGON GUYER MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART Cleveland SECOND GENERATION Married/partnered Office closed REM KOOLHAAS P Divorced/separated P Pritzker Prize laureate OMA Former partner Illustration by Nikki Chung REM_Baby REMS_01_11_rev.indd 1 12/16/10 7:27:54 AM BABY REMS by Paul Makovsky In 1975 Rem Koolhaas, together with Elia and Zoe Zenghelis and Madelon Vriesen- dorp, founded the Office for Metropolitan Architecture. -

Bangkok Rising

ctbuh.org/papers Title: Bangkok Rising Author: Ole Scheeren, Principal, Buro Ole Scheeren Subjects: Architectural/Design Building Case Study Social Issues Keywords: Mixed-Use Public Space Social Interaction Publication Date: 2015 Original Publication: The Future of Tall: A Selection of Written Works on Current Skyscraper Innovations Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Ole Scheeren Bangkok Rising Ole Scheeren, Principal, Buro Ole Scheeren As architecture keeps expanding vertically, unique strategies to (re)address and (re)instate architectures: robot and elephant buildings, with the skyscraper having long become the importance and quality of space within pyramids, UFO’s and vertical structures the predominant typology of architectural architectural production, and its responsibility reminiscent of Louis XIV. It is a city between production in most geographic regions of towards a greater whole – to inhabitants, the tradition and future, between construction hyper-growth, we need to investigate and city, and the society. This, in effect, is what and decay, between subtlety and brutality. Difference only exists in contrast. But what is understand the consequences of vertical generates its difference, its significance – and there to do when “special” exists everywhere stratification and generate alternative its meaning. already? When almost any type or shape typologies of spatial quality and social or character has already been invented, sustainability in the urban realm. MahaNakhon inverted…constructed? is an architectural prototype that generates Babel shared spaces of social interaction and Architecture as process: The building as a In this context, the most boring might manifests the creation of spaces not only within, dialogue – between large scale and small be the most surprising – a needle. -

Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture: an Ethnography of Design

The University of Manchester Research Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture: An Ethnography of Design Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Yaneva, A. (2009). Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture: An Ethnography of Design. (1st ed.) 010 Publlishers. http://books.google.co.uk/books/about/Made_by_the_Office_for_Metropolitan_Arch.html?id=Z4okIn5RvHYChttp:// www.010.nl/catalogue/book.php?id=714 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:29. Sep. 2021 Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture: An Ethnography of Design 010 Publishers Rotterdam 2009 Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture: An Ethnography of Design Albena Yaneva For Bruno Latour Acknowledgements 5 I would like to thank my publisher for encouraging me to systematically explore the large pile of interviews and ethnographic materials collected during my participant observation in the Office for Metropolitan Architecture in Rotterdam (oma) in the period 2002-4.