“The Inner Frontier”: Borders, Narratives, and Cultural Intimacy …

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emerald Cycling Trails

CYCLING GUIDE Austria Italia Slovenia W M W O W .C . A BI RI Emerald KE-ALPEAD Cycling Trails GUIDE CYCLING GUIDE CYCLING GUIDE 3 Content Emerald Cycling Trails Circular cycling route Only few cycling destinations provide I. 1 Tolmin–Nova Gorica 4 such a diverse landscape on such a small area. Combined with the turbulent history I. 2 Gorizia–Cividale del Friuli 6 and hospitality of the local population, I. 3 Cividale del Friuli–Tolmin 8 this destination provides ideal conditions for wonderful cycling holidays. Travelling by bicycle gives you a chance to experi- Connecting tours ence different landscapes every day since II. 1 Kolovrat 10 you may start your tour in the very heart II. 2 Dobrovo–Castelmonte 11 of the Julian Alps and end it by the Adriatic Sea. Alpine region with steep mountains, deep valleys and wonderful emerald rivers like the emerald II. 3 Around Kanin 12 beauty Soča (Isonzo), mountain ridges and western slopes which slowly II. 4 Breginjski kot 14 descend into the lowland of the Natisone (Nadiža) Valleys on one side, II. 5 Čepovan valley & Trnovo forest 15 and the numerous plateaus with splendid views or vineyards of Brda, Collio and the Colli Orientali del Friuli region on the other. Cycling tours Familiarization tours are routed across the Slovenian and Italian territory and allow cyclists to III. 1 Tribil Superiore in Natisone valleys 16 try and compare typical Slovenian and Italian dishes and wines in the same day, or to visit wonderful historical cities like Cividale del Friuli which III. 2 Bovec 17 was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list. -

From the Alps to the Adriatic

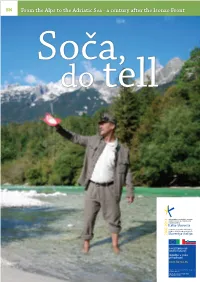

EN From the Alps to the Adriatic Sea - a century after the Isonzo Front Soča, do tell “Alone alone alone I have to be in eternity self and self in eternity discover my lumnious feathers into afar space release and peace from beyond land in self grip.” Srečko Kosovel Dear travellers Have you ever embraced the Alps and the Adriatic with by the Walk of Peace from the Alps to the Adriatic Sea that a single view? Have you ever strolled along the emerald runs across green and diverse landscape – past picturesque Soča River from its lively source in Triglav National Park towns, out-of-the-way villages and open fireplaces where to its indolent mouth in the nature reserve in the Bay of good stories abound. Trieste? Experience the bonds that link Italy and Slove- nia on the Walk of Peace. Spend a weekend with a knowledgeable guide, by yourself or in a group and see the sites by car, on foot or by bicycle. This is where the Great War cut fiercely into serenity a century Tourism experience providers have come together in the T- ago. Upon the centenary of the Isonzo Front, we remember lab cross-border network and together created new ideas for the hundreds of thousands of men and boys in the trenches your short break, all of which can be found in the brochure and on ramparts that they built with their own hands. Did entitled Soča, Do Tell. you know that their courageous wives who worked in the rear sometimes packed clothing in the large grenades instead of Welcome to the Walk of Peace! Feel the boundless experi- explosives as a way of resistance? ences and freedom, spread your wings among the vistas of the mountains and the sea, let yourself be pampered by the Today, the historic heritage of European importance is linked hospitality of the locals. -

United Nations ECE/MP.WAT/2015/10

United Nations ECE/MP.WAT/2015/10 Economic and Social Council Distr.: General 13 November 2015 English only Economic Commission for Europe Meeting of the Parties to the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes Seventh session Budapest, 17–19 November 2015 Item 4(i) of the provisional agenda Draft assessment of the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus in the Isonzo/Soča River Basin Assessment of the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus in the Isonzo/Soča River Basin* Prepared by the secretariat with the Royal Institute of Technology Summary At its sixth session (Rome, 28–30 November 2012), the Meeting of the Parties to the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes requested the Task Force on the Water-Food-Energy-Ecosystems Nexus, in cooperation with the Working Group on Integrated Water Resources Management, to prepare a thematic assessment focusing on the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus for the seventh session of the Meeting of the Parties (see ECE/MP.WAT/37, para. 38 (i)). The present document contains the scoping-level nexus assessment of the Isonzo/Soča River Basin with a focus on the downstream part of the basin. The document is the result of an assessment process carried out according to the methodology described in publication ECE/MP.WAT/46, developed on the basis of a desk study of relevant documentation, an assessment workshop (Gorizia, Italy; 26-27 May 2015), as well as inputs from local experts and officials of Italy. Updates in the process were reported at the meetings of the Task Force. -

Thomas RAINER, Reinhard F. SACHSENHOFER, Gerd RANTITSCH, Uroš HERLEC & Marko VRABEC

Austrian Journal of Earth Sciences Volume 102/2 Vienna 2009 Organic maturity trends across the Variscan discordance in the Alpine-Dinaric Transition Zone (Slovenia, Austria, Italy): Variscan versus Alpidic thermal overprint_________ Thomas RAINER1)3)*), Reinhard F. SACHSENHOFER1), Gerd RANTITSCH1), Uroš HERLEC2) & Marko VRABEC2) 1) KEYWORDS Mining University Leoben, Department for Applied Geosciences and Geophysics, 8700 Leoben, Austria; 2) University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Natural Sciences and Engineering, Department of Geology, Vitrinite reflectance Variscan Discordance 2) Aškerčeva 12, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; Northern Dinarides 3) Present Address: OMV Exploration & Production GmbH, Trabrennstrasse 6-8, 1020 Wien, Austria; Southern Alps Carboniferous *) Corresponding author, [email protected] Eastern Alps Abstract In the Southern Alps and the northern Dinarides the main Variscan deformation event occurred during Late Carboniferous (Bashki- rian to Moscovian) time. It is represented locally by an angular unconformitiy, the “Variscan discordance”, separating the pre-Variscan basement from the post-Variscan (Moscovian to Cenozoic) sedimentary cover. The main aim of the present contribution is to inves- tigate whether a Variscan thermal overprint can be detected and distinguished from an Alpine thermal overprint due to Permo-Meso- zoic basin subsidence in the Alpine-Dinaric Transition Zone in Slovenia. Vitrinite reflectance (VR) is used as a temperature sensitive parameter to determine the thermal overprint of pre- and post-Variscan sedimentary successions in the eastern part of the Southern Alps (Carnic Alps, South Karawanken Range, Paški Kozjak, Konjiška Gora) and in the northern Dinarides (Sava Folds, Trnovo Nappe). Neither in the eastern part of the Southern Alps, nor in the northern Dinarides a break in coalification can be recognized across the “Variscan discordance”. -

Nazionalismo E Localismo a Gorizia by Chiara Sartori MA, Università Di

Identità Forti: Nazionalismo e Localismo a Gorizia By Chiara Sartori M.A., Università di Trieste, 2000 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Italian Studies at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May, 2010 iv © Copyright 2010 by Chiara Sartori v This dissertation by Chiara Sartori is accepted in its present form by the Department of Italian Studies as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date_____________ _________________________________ (Prof. David Kertzer), Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date_____________ _________________________________ (Prof. Massimo Riva), Reader Date_____________ _________________________________ (Prof. Claudio Magris), Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date_____________ _________________________________ (Sheila Bonde), Dean of the Graduate School vi CURRICULUM VITAE Chiara Sartori was born in Gorizia (Italy) on May 11, 1973. While in high school and in college, she worked as freelance journalist for various local media sources (newspapers, radio, private television channels). After she earned the Laurea in Philosophy from the University of Trieste in 2000, she started a career as teacher. She was hired and worked for two years as an elementary teacher in the public school. Contemporarily, she was attending a Master in Philosophical Counseling in Turin. After her wedding in 2002 she followed her husband in Providence. She attended different English classes at Brown University and Drawing classes at RISD. She was then hired as visiting lecturer at Brown University. For one semester she taught three undergraduate-level Italian language courses. In 2003 she started the graduate program in the Department of Italian Studies at Brown University. -

Slo V Eni in Italia

SOMMARIO ISSN 1826-6371 pag. pag. 1 TRIESTE – TRST L’allarme di Sso e Skgz: «A rischio il livello di tutela della minoranza slovena» Lettera dei presidenti delle due confederazioni della minoranza slovena, Walter Bandelj e Ksenija Dobrila 2 TRIESTE – TRST Il secondo albo non passa, le parti da Roberti Tiene banco il confronto sulle modifiche alla legge regionale di tutela della minoranza linguistica slovena 4 UDINE – VIDEN Dalla minoranza slovena una proposta, dalla minoranza non-slovena nessuna Iniziata la ricerca di un compromesso per la modifica della legge regionale di tutela 7 TRIESTE – TRST Lo sviluppo economico parla sloveno, in arrivo quasi due milioni di euro L’articolo 21 della legge statale di tutela della minoranza slovena stanzia ogni anno fondi per Valli del Natisone e del Torre, Resia e Valcanale Bollettino di informazione/Informacijski bilten Slovencev v Italiji Bollettino di informazione/Informacijski Slovencev bilten Sloveni in Italia Sloveni 14 SLOVENIJA – SLOVENIA Rappresentanza parlamentare, la Slovenia aspetta una posizione comune della minoranza Intervista al ministro degli Esteri sloveno, Miro Cerar Anno XXI N° 6 (252) 30 giugno 2019 16 TRIESTE – TRST Più uniti di quanto intendesse Cerar I presidenti di Skgz e Sso, Ksenija Dobrila e Walter Bandelj, e i consiglieri regionali Danilo Slokar e Igor Gabrovec uniti per la rappresentanza parlamentare 18 ITALIA – SLOVENIA Pattuglie miste sui confini italo-sloveni dall’1 luglio L’obiettivo è contrastare l’ingresso di migranti illegali 19 TRIESTE – TRST Quindicinale di informazione Direttore responsabile Giorgio Banchig Fedriga: «Non desidero la chiusura Traduzioni di Veronica Galli, Luciano Lister e Larissa Borghese dei confini tra Italia e Slovenia» Direzione, redazione, amministrazione: L’Italia potrebbe copiare alla Slovenia l’idea del filo spinato. -

HIKING in SLOVENIA Green

HIKING IN SLOVENIA Green. Active. Healthy. www.slovenia.info #ifeelsLOVEnia www.hiking-biking-slovenia.com |1 THE LOVE OF WALKING AT YOUR FINGERTIPS The green heart of Europe is home to active peop- le. Slovenia is a story of love, a love of being active in nature, which is almost second nature to Slovenians. In every large town or village, you can enjoy a view of green hills or Alpine peaks, and almost every Slove- nian loves to put on their hiking boots and yell out a hurrah in the embrace of the mountains. Thenew guidebook will show you the most beauti- ful hiking trails around Slovenia and tips on how to prepare for hiking, what to experience and taste, where to spend the night, and how to treat yourself after a long day of hiking. Save the dates of the biggest hiking celebrations in Slovenia – the Slovenia Hiking Festivals. Indeed, Slovenians walk always and everywhere. We are proud to celebrate 120 years of the Alpine Associati- on of Slovenia, the biggest volunteer organisation in Slovenia, responsible for maintaining mountain trails. Themountaineering culture and excitement about the beauty of Slovenia’s nature connects all generations, all Slovenian tourist farms and wine cellars. Experience this joy and connection between people in motion. This is the beginning of themighty Alpine mountain chain, where the mysterious Dinaric Alps reach their heights, and where karst caves dominate the subterranean world. There arerolling, wine-pro- ducing hills wherever you look, the Pannonian Plain spreads out like a carpet, and one can always sense the aroma of the salty Adriatic Sea. -

HISTORY of the 87Th MOUNTAIN INFANTRY in ITALY

HISTORY of the 87th MOUNTAIN INFANTRY in ITALY George F. Earle Captain, 87th Mountain Infantry 1945 HISTORY of the 87th MOUNTAIN INFANTRY in ITALY 3 JANUARY 1945 — 14 AUGUST 1945 Digitized and edited by Barbara Imbrie, 2004 CONTENTS PREFACE: THE 87TH REGIMENT FROM DECEMBER 1941 TO JANUARY 1945....................i - iii INTRODUCTION TO ITALY .....................................................................................................................1 (4 Jan — 16 Feb) BELVEDERE OFFENSIVE.........................................................................................................................10 (16 Feb — 28 Feb) MARCH OFFENSIVE AND CONSOLIDATION ..................................................................................24 (3 Mar — 31 Mar) SPRING OFFENSIVE TO PO VALLEY...................................................................................................43 (1 Apr — 20 Apr) Preparation: 1 Apr—13 Apr 43 First day: 14 April 48 Second day: 15 April 61 Third day: 16 April 75 Fourth day: 17 April 86 Fifth day: 18 April 96 Sixth day: 19 April 99 Seventh day: 20 April 113 PO VALLEY TO LAKE GARDA ............................................................................................................120 (21 Apr — 2 May) Eighth day: 21 April 120 Ninth day: 22 April 130 Tenth day: 23 April 132 Eleventh and Twelfth days: 24-25 April 149 Thirteenth day: 26 April 150 Fourteenth day: 27 April 152 Fifteenth day: 28 April 155 Sixteenth day: 29 April 157 End of the Campaign: 30 April-2 May 161 OCCUPATION DUTY AND -

Tiere Furlane 10 • Terra Friulana

RIVISTA DI CULTURA DEL TERRITORIO Ottobre 2011 Anno 3 Numero 3 issn 2036-8283 10 N. 10 10 N. Ottobre 2011 Tiere furlane Tiere Le facce sono da funerale, eppure si tratta di una Prima Comunione a Bressa di Campoformido, evento di solito gioioso; l’espressione In copertina: Gianenrico Vendramin, Tiere furlane di sierade, dello stralunato prete sembra un grosso punto di domanda (che cosa Archivio CRAF, Spilimbergo. dobbiamo aspettarci ancora?); il volto di San Domenico Savio, così devotamente esposto, non è tale da imprimere maggiore fi ducia nel futuro. Sopra: Francobollo della serie Italia al lavoro, 1950. La stampigliatura Ed era giorno di festa grande, il Corpus Domini; ma correva l’anno 1919... AMG - FTT signifi ca Allied Military Government - Free Territory of Trieste. Si fa buio a Malga Crostis, agosto 1970. Diapositiva in bianco e nero di Gualtiero Simonetti. TIERE FURLANE 2 • TERRA FRIULANA Plui salams e mancul stradis Un mio simpatico nemico politico tradizione di secoli. – perché me lo ha insegnato mio mi accusa di “andare sempre per La settimana scorsa ero alla festa padre. Per il resto coltivo forag- sagre”. È vero, sono un assiduo del maiarut a Surisins di Sotto, gere per la stalla, asparagi, meli frequentatore delle feste paesane: dove pare che il maiarut sia più e viti –. ciò mi consente di sentire gli umori genuino di quello di Surisins di Immagino che si alzi ad ore ante- della gente ma, soprattutto, di Sopra. Dopo qualche bicchiere di lucane, e con lui tutta la famiglia. capire qual è lo “stato dell’arte” di vino intavolai il discorso con un Devono avere una capacità lavo- tanti prodotti locali. -

Slovit 7-8 08

SOMMARIO ISSN 1826-6371 1 TUTELA Politici-slavisti e tutela dei dialetti Riflessione a margine delle proposte del sen. Saro e del consigliere regionale Novelli 2 REGIONE La lunga storia dei dialetti della Slavia friulana Il consigliere regionale Gabrovec (SSk) interviene sulla proposta di tutelare le varianti dialettali 3 REGIONE La Commissione slovena al completo Eletti i rappresentanti sloveni nell’organismo consultivo per la minoranza slovena 5 GORIZIA Sso ed Skgz ringraziano il prefetto De Lorenzo Le due organizzazioni slovene hanno chiesto alla Slovenia il conferimento di un’onorificenza al prefetto 6 LA POLEMICA Critiche alla relazione storica del governo sloveno Il Piccolo interviene duramente sui presunti «ruzzoloni» sulla connotazione etnica data ad alcuni fatti storici 9 ARCHIVI Anno X N° 7-8 (129-130) 31 agosto 2008 Crimini di guerra italiani, il giudice indaga Le armate fasciste dal 1941 al 1943 lasciarono una scia di sangue in Jugoslavia e Grecia 12 STORIA Trieste e Gorizia senza confine: un futuro tutto da inventare Dal saggio «Itali-Slovenia, ovvero del confine che non c’è più» 15 SLAVIA FRIULANA-BENE#IJA Emesse le carte d’identità bilingui nei comuni di Taipana e Grimacco Passo in avanti per tutta la comunità slovena 18 LETTERATURA Boris Pahor:«Dopo Necropoli altri due romanzi» A colloquio con lo scrittore di lingua slovena, che ha compiuto 95 anni A margine delle proposte del sen. Saro e del consigliere regionale Novelli TUTELA Politici-slavisti e tutela dei dialetti L’apparteneza di un dialetto ad una lingua non si stabilisce per legge itorniamo sulla questione della tutela dei dialetti delle ni, appartenenti, come i dialetti sloveni delle province di Valli del Natisone, del Torre e di Resia non senza una Gorizia e Trieste, al gruppo dei dialetti sloveni comunemente Rcerta sensazione di fastidio a causa della ripetitività definiti del Litorale. -

Nuovo Regolamento Di Polizia Urbana

UNION TERITORIÂL INTERCOMUNÂL DAL NADISON - NEDIŠKA MEDOBČINSKA TERITORIALNA UNIJA REGOLAMENTO DI POLIZIA URBANA NORME PER LA CIVILE CONVIVENZA BUTTRIO CIVIDALE DRENCHIA GRIMACCO MANZANO DEL FRIULI MOIMACCO PREMARIACCO PREPOTTO PULFERO REMANZACCO SAN GIOVANNI SAN LEONARDO SAN PIETRO SAVOGNA STREGNA AL NATISONE AL NATISONE 1 UNION TERITORIÂL INTERCOMUNÂL DAL NADISON - NEDIŠKA MEDOBČINSKA TERITORIALNA UNIJA INDICE TITOLO I DISPOSIZIONI GENERALI Art. 1 Finalità, oggetto e ambito di applicazione p. 5 Art. 2 Procedure per l'accertamento delle violazioni e per l'applicazione p. 6 delle Sanzioni amministrative Art. 3 Sospensione delle autorizzazioni, dei nulla osta e delle p. 6 autorizzazioni in deroga previste dalle norme del Regolamento per lo svolgimento di determinate attività Art. 4 Accertamento delle violazioni p. 7 TITOLO II NORME DI COMPORTAMENTO CAPO I SICUREZZA URBANA, PUBBLICA INCOLUMITÀ E FRUIZIONE DEGLI SPAZI PUBBLICI – ORDINE DI ALLONTANAMENTO Art. 5 Incolumità pubblica e Sicurezza Urbana - Definizioni p. 7 Art. 6 Zone urbane di particolare rilevanza dove operano l’ordine di p. 8 allontanamento e la limitazione degli orari di somministrazione e vendita degli alcolici Art. 7 Fruibilità di spazi ed aree pubbliche – divieto di occupazione del p. 8 suolo aperto all’uso pubblico Art. 8 Divieto di stazionamento lesivo del diritto di circolazione p. 9 Art. 9 Limitazione degli orari per la vendita e per la somministrazione di p. 9 alcolici Art. 10 Procedure per l’adozione dell’ordine di allontanamento p. 10 Art. 11 Norme comportamentali per la partecipazione a manifestazioni p. 11 dinamiche Art. 12 Provvedimenti a tutela della vivibilità urbana e di contrasto al p. 11 degrado e all’abuso di sostanze alcoliche CAPO II DECORO E ATTI VIETATI SULLE AREE PUBBLICHE Art. -

Friuli Venezia Giulia: Una Terra Da Scoprire E Da Gustare

FRIULI Una terra VENEZIA da scoprire e GIULIA da gustare Temi e suggestioni per il vostro viaggio di gruppo su misura FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA: UNA TERRA DA SCOPRIRE E DA GUSTARE ra un viaggio e l’altro in luoghi lontani, ci riserviamo in Friuli Venezia Giulia Til piacere più grande: accompagnarVi alla scoperta della nostra terra. Sarete ospiti Il Friuli Venezia Giulia non è una regione qualunque. È una regione orientale d’Italia, che evoca distanze e altri mondi, concentrando in sé la complessità dell’Europa, senza mai smettere di essere fedele alle proprie tradizioni e a uno spirito della nostra passione di autentica ospitalità. Lo dice uno che è nato da una famiglia di osti, che conosce il profumo dell’osteria, parola sacra derivante dal latino hospes: ospite. Scegliere di viaggiare con noi, significa scoprire e vivere questo Friuli Venezia Giulia, lasciarsi scaldare da quel fogolâr che è il simbolo della nostra terra. Con Armonie e sapori del Friuli comprenderete che la nostra regione va stappata come una bottiglia del nostro buon vino, per poi assaporare le sue atmosfere lentamente sprigionate, mettendo d’accordo i cinque sensi. Sentirete che per capire il Friuli Venezia Giulia non bastano cinque siti Unesco, un paesaggio vario come il mondo, la storia universale di Aquileia, i lampi longobardi di Cividale del Friuli, la piazza fronte mare più monumentale d’Europa. La nostra terra è qualcosa di più: è mistero, è sensualità, è intimità. Sono fuochi antichi. Sono lingue con una musica nuova. Sono calici di amicizia. Benvenuti a casa Vostra Corrado Liani Responsabile del prodotto 2 3 PERCHÉ scoprire IL FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA Un piccolo compendio dell’Universo, dove s’incontra l’Europa 2 3 4 5 6 1 7 l nome “Friuli Venezia Giulia” racchiude on Armonie e sapori del Friuli potrete 1.