TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITÄT MÜNCHEN Role of Land Governance in Improving Tenure Security in Zambia: Towards a Strategic Framework F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OF ZAMBIA ...Three Infants Among Dead After Overloaded Truck Tips Into

HOME NEWS: FEATURE: ENTERTAINMENT: SPORT: KK in high Rising suicide RS\ FAZ withdraws spirits, says cases source of industry has from hosting Chilufya– p3 concern- p17 potential to U-23 AfCON grow’ – p12 tourney – p24 No. 17,823 timesofzambianewspaper @timesofzambia www.times.co.zm TIMES SATURDAY, JULY 22, 2017 OF ZAMBIA K10 ...Three infants among dead after overloaded 11 killed as truck tips into drainage in Munali hills truck keels over #'%$#+,$ drainage on the Kafue- goods –including a hammer-mill. has died on the spot while four Mission Hospital,” Ms Katongo a speeding truck as the driver “RTSA is saddened by the other people sustained injuries in said. attempted to avoid a pothole. #'-$%+Q++% Mazabuka road on death of 11 people in the Munali an accident which happened on She said the names of the The incident happened around +#"/0$ &301"7,'%&2T &'**1 20$L'! !!'"#,2 -, 2&# $3# Thursday. victims were withheld until the 09:40 hours in the Mitec area on #-++-$ Police said the 40 passengers -Mazabuka road. The crash The accident happened on the next of keen were informed. the Solwezi-Chingola road. ++0+% .#-.*#Q +-,% travelling in the back of a Hino could have been avoided had the Zimba-Kalomo Road at Mayombo Ms Katongo said in a similar North Western province police truck loaded with an assortment passengers used appropriate area. ',!'"#,2Q L'4#V7#0V-*" -7 -$ !&'#$36#,1'-)'"#,2'L'#"2&# 2&#+ 2&0## $Q &4# of goods - including a hammer means of transport,” he said. Police spokesperson Esther Hospital township in Chama deceased as Philip Samona, saying died on the spot while mill - were heading to various Southern Province Minister Katongo said in a statement it district, died after he was hit by he died on the spot. -

SUMMARY REPORT Strengthening Investment Climate Assessment

Republic of Zambia Ministry of Commerce, Trade and Industry NEPAD-OECD AFRICA INVESTMENT INITIATIVE ROUNDTABLE Lusaka, Zambia, 27-28 November 2007 SUMMARY REPORT Strengthening Investment Climate Assessment and Reform in NEPAD Countries Lusaka Regional Roundtable Mulungushi International Conference Centre Lusaka, Zambia 27-28 November 2007 Hosted by the Government of the Republic of Zambia Jointly organised by the New Partnership for Africa‘s Development (NEPAD) and the Investment Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) 1 2 Republic of Zambia Ministry of Commerce, Trade and Industry NEPAD-OECD AFRICA INVESTMENT INITIATIVE ROUNDTABLE Lusaka, Zambia, 27-28 November 2007 SUMMARY REPORT Strengthening Investment Climate Assessment and Reform in NEPAD Countries Lusaka Regional Roundtable Mulungushi International Conference Centre Lusaka, Zambia 27-28 November 2007 Hosted by the Government of the Republic of Zambia Jointly organised by the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) and the Investment Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Supported by The Governments of Belgium, Germany and Japan In partnership with 3 The Honourable Felix Mutati, Minister for Commerce, Trade and Industry of Zambia greets the Honourable Prof. Semakula Kiwanuka, Minister of State for Finance, Planning and Economic Development (Investments) of Uganda in the presence of Prof Firmino Mucavele, Executive Head, NEPAD Secretariat and Mr Mario Amano, Deputy Secretary General, OECD 4 Table -

Zambia Country Profile Monitoring, Reporting and Verification for REDD+

OCCASIONAL PAPER Zambia country profile Monitoring, reporting and verification for REDD+ Michael Day Davison Gumbo Kaala B. Moombe Arief Wijaya Terry Sunderland OCCASIONAL PAPER 113 Zambia country profile Monitoring, reporting and verification for REDD+ Michael Day Center for International Forestry Research Davison Gumbo Center for International Forestry Research Kaala B. Moombe Center for International Forestry Research Arief Wijaya Center for International Forestry Research Terry Sunderland Center for International Forestry Research Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) Occasional Paper 113 © 2014 Center for International Forestry Research Content in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ ISBN 978-602-1504-42-0 Day M, Gumbo D, Moombe KB, Wijaya A and Sunderland T. 2014. Zambia country profile: Monitoring, reporting and verification for REDD+. Occasional Paper 113. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR. Photo by Terry Sunderland CIFOR Jl. CIFOR, Situ Gede Bogor Barat 16115 Indonesia T +62 (251) 8622-622 F +62 (251) 8622-100 E [email protected] cifor.org We would like to thank all donors who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Fund. For a list of Fund donors please see: https://www.cgiarfund.org/FundDonors Any views expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of CIFOR, the editors, the authors’ institutions, the financial sponsors or the -

C:\Users\Public\Documents\GP JOBS\Gazette\Gazette 2017

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA Price: K10.00 net Annual Subscription: Within Lusaka—K300.00 Published by Authority Outside Lusaka—K350.00 No. 6584] Lusaka, Friday, 30th June, 2017 [Vol. LIII, No. 42 TABLE OF CONTENTS GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 426 OF 2017 [7523640 Gazette Notices No. Page The Lands and Deeds Registry Act (Chapter 185 of the Laws of Zambia) Lands and Deeds Registry Act: (Section 56) Notice of Intention to Issue Duplicate Document 425 499 Notice of Intention to Issue Duplicate Document 426 499 Notice of Intention to Issue Duplicate Document 427 499 Notice of Intention to Issue a Duplicate Certificate of Title Companies Act: FOURTEEN DAYS after the publication of this notice I intend to issue Notice Under Section 361 428 449 a Certificate of Title No. 77433 in the name of Shengebu Stanley Notice Under Section 361 429 500 Shengebu in respect of Stand No. LUS/30340 in extent of 0.5907 Notice Under Section 361 430 500 hectares situate in the Lusaka Province of the Republic of Zambia. Notice Under Section 361 431 500 Notice Under Section 361 432 500 All persons having objections to the issuance of the duplicate Notice Under Section 361 433 500 certificate of title are hereby required to lodge the same in writing Notice Under Section 361 434 501 with the Registrar of Lands and Deeds within fourteen days from Notice Under Section 361 435 501 the date of publication of this notice. Notice Under Section 361 436 501 E. TEMBO, Notice Under Section 361 437 501 REGISTRY OF LANDS AND DEEDS Registrar Notice Under Section 361 438 501 Notice Under Section 361 439 501 P.O. -

Education Act.Pdf

The Laws of Zambia REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA THE EDUCATION ACT CHAPTER 134 OF THE LAWS OF ZAMBIA CHAPTER 134 THE EDUCATION ACT THE EDUCATION ACT ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I PRELIMINARYPART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title 2. Interpretation 3. Application 4. Functions of Minister 5. Educational regions 6. Chief Education Officers PART II NATIONAL, REGIONAL AND LOCAL COUNCILS OF EDUCATIONPART II NATIONAL, REGIONAL AND LOCAL COUNCILS OF EDUCATION 7. National Council of Education 8. Regional Councils of Education 9. Local Councils of Education 10. Constitution and procedure of National, Regional and Local Councils of Education Copyright Ministry of Legal Affairs, Government of the Republic of Zambia The Laws of Zambia PART III GOVERNMENT AND AIDED SCHOOLSPART III GOVERNMENT AND AIDED SCHOOLS 11. Establishment, maintenance and closure of Government schools and hostels 12. Regulations governing Government and aided schools and hostels PART IV REGISTRATION OF PRIVATE SCHOOLSPART IV REGISTRATION OF PRIVATE SCHOOLS 13. Registration and renewal of registration 14. Registration 15. Register 16. Cancellation of registration of private schools 17. Minister's determination to be final 18. Offences 18A. Publication of list of registered private schools 18B. Saving of registration of private schools 18C. Regulations PART V BOARDS OF GOVERNORSPART V BOARDS OF GOVERNORS 19. Establishment and incorporation of boards 20. Functions of boards 21. Funds of boards 22. Accounts and audit 23. Regulations PART VI GENERAL PROVISIONSPART VI GENERAL PROVISIONS Copyright Ministry of Legal Affairs, Government of the Republic of Zambia The Laws of Zambia 24. No refusal of admission on grounds of race or religion 25. Exemption of pupils from religious observances 26. -

1"Torking Paper No. 2 2

COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT ON HUMAN SETTLEMENTS AND NATURAL RESOURCE SYSTEMS ANALYSIS 1"torking Paper No. 2 2 Clark University Institute for Development Anthropology International Development Program 99 Collier Street 950 Main Street Suite 302, P.O. Box 2207 Worcester, MA 01610 Binghamton, NY 13902 A HISTORY OF DEVELOPMENT IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: THE ZAMBIAN PORTION OF THE MIDDLE ZAMBEZI VALLEY AND THE LAKE KARIBA BASIN by Thayer Scudder Institute of Development Anthropology and California Institute of Technology August 1985 Clark University/Institute for Development Anthropology Cooperative Agreement on Human Settlement and Natural Resource Systems Analysis COITUTS 1. INTRODUCTION . 1 2. OVERVIEW . o . *. s.*. # o a o 3 3. 1901-1931: THE LOCAL ECONOMY DURING THE INITIAL YEARS OF ADMINISTRATION AND THE PROBLEM OF FAMINE. .. ... 7 4. 1932-1954: ATTEMPTS TO ALLEVIATE FAMINE . .. 11 5. 1955-1974: THE YEARS OF DEVELOPMENT . .. .. 14 a. Introduction . .. ... .. ... 14 b. The Background of the Kariba Dam Project .. 14 c. Policy and Institutional Infrastructure for Gwembe Development . ... ... ... 177 d. Physical and Social Infrastructure ... ......... 25 e. The Lake Kariba Gillnet Fishery .... ............. 27 f. Tsetse Control and the Buildup in Cattle Numbers . 30 g. Rainfed Agriculture ..... ................. 37 h. Flood Water Cultivation and Irrigation ... .. 41 (1) Flood Water Cultivation .............. 42 (2) Gravity Flow and Pump Irrigation ... 43 i. Coal Mining and Township Development ... .. 47 6. 1975-1983: ECONOMIC DOWNTURN AND THE COLLAPSE OF THE DISTRICT ECONOMY. .. .. 49 a. At the District and Village Level . ... .. .. 49 b. At the National Level. .. ... 52 c. Local Responses to Downturn . .. .. 53 7. THE LONGSTANDING CAUSES OF DOWNTURN. ... ... ... 56 a. Deteriorating International Terms of Trade . -

The Opportunity Costs of REDD+ in Zambia

The Opportunity Costs of REDD+ in Zambia This assignment was undertaken on request by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations in Zambia under contract Number: UNJP/ZAM/068/UNJ – 09 – 12 - PHS Team Director: Saviour Chishimba Consultant: Monica Chundama Data Analyst: Akakandelwa Akakandelwa Technical Team Chithuli Makota (REDD+) Edmond Kangamugazi (Economist) Saul Banda, Jnr. (Livelihoods) Authors: Saviour Chishimba (Lead Author) Monica Chundama Akakandelwa Akakandelwa Citation: Chishimba, S., Chundama, M. & Akakandelwa, A. (2013). The Opportunity Costs of REDD+ in Zambia. The views expressed in this document are not of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, but of the consulting firm. The Opportunity Costs of REDD+ in Zambia FINAL REPORT Saviour Chishimba (Lead Author) Monica Chundama Akakandelwa Akakandelwa 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The directors and staff of Even Ha’Ezer Consult Limited are indebted to Mr. Deuteronomy Kasaro and Mrs Maurine Mwale of the Forestry Department and Dr. Julian Fox and Ms. Celestina Lwatula of the UN-REDD Programme at FAO for providing the necessary logistical support, without which, the assignment would not have been completed. Saviour Chishimba Chief Executive Officer Even Ha’Ezer Consult Limited EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION Preserving forests entails foregoing the benefits that would have been generated by alternative deforesting and forest degrading land uses (for example agriculture, charcoal burning, etc). The difference between the benefits provided by the forest and those that would have been provided by the alternative land use is the opportunity cost of avoiding deforestation and forest degradation. Foregoing the economic benefits that come with deforestation and forest degradation will only make sense to policy makers and the general population if alternatives that are advanced under REDD+ offer sufficient sustainable benefits. -

2000 Census of Population and Housing

2000 Census of Population and Housing Published by Central Statistical Office, P. O. Box 31908, Copperbelt, Zambia. Tel: 260-01-251377/253468 Fax: 260-01-253468 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.zamstats.gov.zm September, 2004 COPYRIGHT RESERVED Extracts may be published if Sources are duly acknowledged. Preface The 2000 Census of Population and Housing was undertaken from 16th October to 15th November 2000. This was the fourth census since Independence in 1964. The other three were carried out in 1969, 1980 and 1990. The 2000 Census operations were undertaken with the use of Grade 11 pupils as enumerators, Primary School Teachers as supervisors, Professionals from within Central Statistical Office and other government departments being as Trainers and Management Staff. Professionals and Technical Staff of the Central Statistical Office were assigned more technical and professional tasks. This report presents detailed analysis of issues on evaluation of coverage and content errors; population, size, growth and composition; ethnicity and languages; economic and education characteristics; fertility; mortality and disability. The success of the Census accrues to the dedicated support and involvement of a large number of institutions and individuals. My sincere thanks go to Co-operating partners namely the British Government, the Japanese Government, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the Norwegian Government, the Dutch Government, the Finnish Government, the Danish Government, the German Government, University of Michigan, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) and the Canadian Government for providing financial, material and technical assistance which enabled the Central Statistical Office carry out the Census. -

REPORT for LOCAL GOVERNANCE.Pdf

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON LOCAL GOVERNANCE, HOUSING AND CHIEFS’ AFFAIRS FOR THE FIFTH SESSION OF THE NINTH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY APPOINTED ON 19TH JANUARY 2006 PRINTED BY THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF ZAMBIA i REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON LOCAL GOVERNANCE, HOUSING AND CHIEFS’ AFFAIRS FOR THE FIFTH SESSION OF THE NINTH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY APPOINTED ON 19TH JANUARY 2006 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEMS PAGE 1. Membership 1 2. Functions 1 3. Meetings 1 PART I 4. CONSIDERATION OF THE 2006 REPORT OF THE HON MINISTER OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND HOUSING ON AUDITED ACCOUNTS OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT i) Chibombo District Council 1 ii) Luangwa District Council 2 iii) Chililabombwe Municipal Council 3 iv) Livingstone City Council 4 v) Mungwi District Council 6 vi) Solwezi Municipal Council 7 vii) Chienge District Council 8 viii) Kaoma District Council 9 ix) Mkushi District Council 9 5 SUBMISSION BY THE PERMANENT SECRETARY (BEA), MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND NATIONAL PLANNING ON FISCAL DECENTRALISATION 10 6. SUBMISSION BY THE PERMANENT SECRETARY, MINISTRY OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND HOUSING ON GENERAL ISSUES 12 PART II 7. ACTION-TAKEN REPORT ON THE COMMITTEE’S REPORT FOR 2005 i) Mpika District Council 14 ii) Chipata Municipal Council 14 iii) Katete District Council 15 iv) Sesheke District Council 15 v) Petauke District Council 16 vi) Kabwe Municipal Council 16 vii) Monze District Council 16 viii) Nyimba District Council 17 ix) Mambwe District Council 17 x) Chama District Council 18 xi) Inspection Audit Report for 1st January to 31st August 2004 18 xii) Siavonga District Council 18 iii xiii) Mazabuka Municipal Council 19 xiv) Kabompo District Council 19 xv) Decentralisation Policy 19 xvi) Policy issues affecting operations of Local Authorities 21 xvii) Minister’s Report on Audited Accounts for 2005 22 PART III 8. -

Zambia Managing Water for Sustainable Growth and Poverty Reduction

A COUNTRY WATER RESOURCES ASSISTANCE STRATEGY FOR ZAMBIA Zambia Public Disclosure Authorized Managing Water THE WORLD BANK 1818 H St. NW Washington, D.C. 20433 for Sustainable Growth and Poverty Reduction Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized THE WORLD BANK Zambia Managing Water for Sustainable Growth and Poverty Reduction A Country Water Resources Assistance Strategy for Zambia August 2009 THE WORLD BANK Water REsOuRcEs Management AfRicA REgion © 2009 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgement on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete infor- mation to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. -

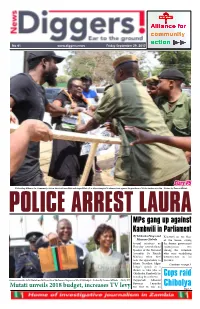

Cops Raid Chibolya

No 41 www.diggers.news Friday September 29, 2017 Story P5 Police drag Alliance for Community Action director Laura Miti and singer Pilato (l) as they attempted to demonstrate against the purchase of 42 fire tenders at $42m - Picture by Tenson Mkhala POLICE ARREST LAURA MPs gang up against Kambwili in Parliament By Mukosha Funga and Kambwili on the floor Mirriam Chabala of the house, saying Several ministers on the former government Thursday overwhelmed spokesperson was Speaker of the National among the criminals Assembly Dr Patrick who were vandalising Matibini when they infrastructure in his took the opportunity to province. debate President Edgar Continues on page 3 Lungu’s speech as a chance to take jabs at Chishimba Kambwili for branding them thieves. Cops raid Finance minister Felix Mutati and wife arrive at Parliament to present the 2018 budget - Picture by Tenson Mkhala. Story P4 Copperbelt Minister Bowman Lusambo was first to take on Chibolya Mutati unveils 2018 budget, increases TV levy Page 2 2. Local News Friday September 29, 2017 By Sipilisiwe Ncube Minister of Home Affairs Stephen Kampyongo says he will not spare any criminals regardless of who they are. Police raid Chibolya again And Kampyongo has described Chishimba Kambwili as a drowning man trying to hang-on to others for survival. Police last night combined forces with the Drug Enforcement Commission, Immigration and other security wings to raid Chibolya compound in a continued crack down on illicit drugs in Lusaka. The officers recovered drums, bags and safes filled with all sorts of narcotic drugs and apprehended the suspects among them, an ex-convict popularly known as Seven Spirits. -

Republic of Zambia

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA Price: K10.00 net Annual Subscription: Within Lusaka—K300.00 Published byAuthority Outside Lusaka—K350.00 No. 6634] Lusaka, Friday, 29th December, 2017 [Vol. LIII, No. 92 GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 993 OF 2017 Hon. Magaret D. Mwanakatwe, MP Hon. Felix Mutati, MP The Statutory Functions Act Minister of Commerce, Trade Minister of Finance (Laws, Volume 1, Cap. 3) and Industry, was authorised to travel to China on official Temporary Transfer of Statutory Functions duty from 7th to16th August, IT IS NOTIFIED for public information that the Honourable Minister 2017 set out in Column A hereunder were authorised to be out of the Hon. Harry Kalaba, MP Hon. Rev. Godfridah country on Government business. Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sumaili, MP, Minister of In exercise of the powers contained in Section (4) of the Statutory was autorised to travel to National Guidance and Functions Act, Cap. 3 of the Laws of Zambia, the President did South Africa on official duty ReligiousAffairs confirm the appointment of the Honourable Ministers set out in from 5th to 22nd August, 2017 Column B hereunder to temporarily perform the duties of the Hon.Magaret D. Mwanakatwe, MP Hon. Michael Z. J. Honourable Ministers set out in Column A. Minister of Commerce, Trade Katambo, MP, Minister of Column A Column B and Industry, was authorised to Fisheries and Livestock travel to South Africa on official Hon. Lawrence Sichalwe, MP Hon. Emerine Kabanshi, MP duty from 15th to 21st August, MinisterofChiefsand Minister of Community 2017 traditional affairs was Development, and Social authorised to travel to Services Hon.