SUMMARY REPORT Strengthening Investment Climate Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OF ZAMBIA ...Three Infants Among Dead After Overloaded Truck Tips Into

HOME NEWS: FEATURE: ENTERTAINMENT: SPORT: KK in high Rising suicide RS\ FAZ withdraws spirits, says cases source of industry has from hosting Chilufya– p3 concern- p17 potential to U-23 AfCON grow’ – p12 tourney – p24 No. 17,823 timesofzambianewspaper @timesofzambia www.times.co.zm TIMES SATURDAY, JULY 22, 2017 OF ZAMBIA K10 ...Three infants among dead after overloaded 11 killed as truck tips into drainage in Munali hills truck keels over #'%$#+,$ drainage on the Kafue- goods –including a hammer-mill. has died on the spot while four Mission Hospital,” Ms Katongo a speeding truck as the driver “RTSA is saddened by the other people sustained injuries in said. attempted to avoid a pothole. #'-$%+Q++% Mazabuka road on death of 11 people in the Munali an accident which happened on She said the names of the The incident happened around +#"/0$ &301"7,'%&2T &'**1 20$L'! !!'"#,2 -, 2&# $3# Thursday. victims were withheld until the 09:40 hours in the Mitec area on #-++-$ Police said the 40 passengers -Mazabuka road. The crash The accident happened on the next of keen were informed. the Solwezi-Chingola road. ++0+% .#-.*#Q +-,% travelling in the back of a Hino could have been avoided had the Zimba-Kalomo Road at Mayombo Ms Katongo said in a similar North Western province police truck loaded with an assortment passengers used appropriate area. ',!'"#,2Q L'4#V7#0V-*" -7 -$ !&'#$36#,1'-)'"#,2'L'#"2&# 2&#+ 2&0## $Q &4# of goods - including a hammer means of transport,” he said. Police spokesperson Esther Hospital township in Chama deceased as Philip Samona, saying died on the spot while mill - were heading to various Southern Province Minister Katongo said in a statement it district, died after he was hit by he died on the spot. -

TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITÄT MÜNCHEN Role of Land Governance in Improving Tenure Security in Zambia: Towards a Strategic Framework F

TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITÄT MÜNCHEN Lehrstuhl für Bodenordnung und Landentwicklung Institut für Geodäsie, GIS und Landmanagement Role of Land Governance in Improving Tenure Security in Zambia: Towards a Strategic Framework for Preventing Land Conflicts Anthony Mushinge Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Ingenieurfakultät Bau Geo Umwelt der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktor-Ingenieurs genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. Ir. Walter Timo de Vries Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. Prof. Dr.-Ing. Holger Magel 2. Prof. Dr. sc. agr. Michael Kirk (Philipps Universität Marburg) 3. Prof. Dr. Jaap Zevenbergen (University of Twente / Niederlande) Die Dissertation wurde am 25.04.2017 bei der Technischen Universität München eingereicht und durch die Ingenieurfakultät Bau Geo Umwelt am 25.08.2017 angenommen. Abstract Zambia is one of the countries in Africa with a high frequency of land conflicts. The conflicts over land lead to tenure insecurity. In response to the increasing number of land conflicts, the Zambian Government has undertaken measures to address land conflicts, but the measures are mainly curative in nature. But a conflict sensitive land governance framework should address both curative and preventive measures. In order to obtain insights about the actual realities on the ground, based on a case study approach, the research examined the role of existing state land governance framework in improving tenure security in Lusaka district, and established how land conflicts affect land tenure security. The research findings show that the present state land governance framework is malfunctional which cause land conflicts and therefore, tenure insecurity. The research further reveals that state land governance is characterised by defective legal and institutional framework and inappropriate technical (i.e. -

C:\Users\Public\Documents\GP JOBS\Gazette\Gazette 2017

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA Price: K10.00 net Annual Subscription: Within Lusaka—K300.00 Published by Authority Outside Lusaka—K350.00 No. 6584] Lusaka, Friday, 30th June, 2017 [Vol. LIII, No. 42 TABLE OF CONTENTS GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 426 OF 2017 [7523640 Gazette Notices No. Page The Lands and Deeds Registry Act (Chapter 185 of the Laws of Zambia) Lands and Deeds Registry Act: (Section 56) Notice of Intention to Issue Duplicate Document 425 499 Notice of Intention to Issue Duplicate Document 426 499 Notice of Intention to Issue Duplicate Document 427 499 Notice of Intention to Issue a Duplicate Certificate of Title Companies Act: FOURTEEN DAYS after the publication of this notice I intend to issue Notice Under Section 361 428 449 a Certificate of Title No. 77433 in the name of Shengebu Stanley Notice Under Section 361 429 500 Shengebu in respect of Stand No. LUS/30340 in extent of 0.5907 Notice Under Section 361 430 500 hectares situate in the Lusaka Province of the Republic of Zambia. Notice Under Section 361 431 500 Notice Under Section 361 432 500 All persons having objections to the issuance of the duplicate Notice Under Section 361 433 500 certificate of title are hereby required to lodge the same in writing Notice Under Section 361 434 501 with the Registrar of Lands and Deeds within fourteen days from Notice Under Section 361 435 501 the date of publication of this notice. Notice Under Section 361 436 501 E. TEMBO, Notice Under Section 361 437 501 REGISTRY OF LANDS AND DEEDS Registrar Notice Under Section 361 438 501 Notice Under Section 361 439 501 P.O. -

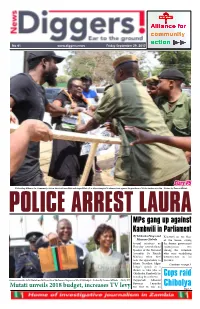

Cops Raid Chibolya

No 41 www.diggers.news Friday September 29, 2017 Story P5 Police drag Alliance for Community Action director Laura Miti and singer Pilato (l) as they attempted to demonstrate against the purchase of 42 fire tenders at $42m - Picture by Tenson Mkhala POLICE ARREST LAURA MPs gang up against Kambwili in Parliament By Mukosha Funga and Kambwili on the floor Mirriam Chabala of the house, saying Several ministers on the former government Thursday overwhelmed spokesperson was Speaker of the National among the criminals Assembly Dr Patrick who were vandalising Matibini when they infrastructure in his took the opportunity to province. debate President Edgar Continues on page 3 Lungu’s speech as a chance to take jabs at Chishimba Kambwili for branding them thieves. Cops raid Finance minister Felix Mutati and wife arrive at Parliament to present the 2018 budget - Picture by Tenson Mkhala. Story P4 Copperbelt Minister Bowman Lusambo was first to take on Chibolya Mutati unveils 2018 budget, increases TV levy Page 2 2. Local News Friday September 29, 2017 By Sipilisiwe Ncube Minister of Home Affairs Stephen Kampyongo says he will not spare any criminals regardless of who they are. Police raid Chibolya again And Kampyongo has described Chishimba Kambwili as a drowning man trying to hang-on to others for survival. Police last night combined forces with the Drug Enforcement Commission, Immigration and other security wings to raid Chibolya compound in a continued crack down on illicit drugs in Lusaka. The officers recovered drums, bags and safes filled with all sorts of narcotic drugs and apprehended the suspects among them, an ex-convict popularly known as Seven Spirits. -

Republic of Zambia

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA Price: K10.00 net Annual Subscription: Within Lusaka—K300.00 Published byAuthority Outside Lusaka—K350.00 No. 6634] Lusaka, Friday, 29th December, 2017 [Vol. LIII, No. 92 GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 993 OF 2017 Hon. Magaret D. Mwanakatwe, MP Hon. Felix Mutati, MP The Statutory Functions Act Minister of Commerce, Trade Minister of Finance (Laws, Volume 1, Cap. 3) and Industry, was authorised to travel to China on official Temporary Transfer of Statutory Functions duty from 7th to16th August, IT IS NOTIFIED for public information that the Honourable Minister 2017 set out in Column A hereunder were authorised to be out of the Hon. Harry Kalaba, MP Hon. Rev. Godfridah country on Government business. Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sumaili, MP, Minister of In exercise of the powers contained in Section (4) of the Statutory was autorised to travel to National Guidance and Functions Act, Cap. 3 of the Laws of Zambia, the President did South Africa on official duty ReligiousAffairs confirm the appointment of the Honourable Ministers set out in from 5th to 22nd August, 2017 Column B hereunder to temporarily perform the duties of the Hon.Magaret D. Mwanakatwe, MP Hon. Michael Z. J. Honourable Ministers set out in Column A. Minister of Commerce, Trade Katambo, MP, Minister of Column A Column B and Industry, was authorised to Fisheries and Livestock travel to South Africa on official Hon. Lawrence Sichalwe, MP Hon. Emerine Kabanshi, MP duty from 15th to 21st August, MinisterofChiefsand Minister of Community 2017 traditional affairs was Development, and Social authorised to travel to Services Hon. -

Ng'andu, Chilufya in Strong Verbal Exchange Over Accountability

No 672 K10 www.diggers.news Friday April 24, 2020 COVID DONATIONS RAISE CONCERNS ...Ng’andu, Chilufya in strong verbal exchange over accountability By Stuart Lisulo THE Ministry of Finance has ordered that all government entities must submit income and expenditure returns on all COVID-19 funds received from the Treasury by 5th of every month to Chingola couple the Office of the Accountant General. And Secretary to the Treasury Fredson Yamba has advised all companies, individuals wishing to donate tests positive for COVID-19-related funds to deposit the cash into a GRZ bank account. Sources have told News Diggers! that during a COVID-19 meeting chaired by Vice-President Inonge COVID-19 Wina on Wednesday, a sharp exchange of words ensued between Finance Minister Dr Bwalya Ng’andu and Health By Zondiwe Mbewe Minister Dr Chitalu Chilufya over accountability regarding HEALTH Minister Dr Chitalu Chilufya says a Chingola pandemic funds. couple that recently traveled to Dar-es-Salaam via Nakonde The source explained that Ng’andu expressed dissatisfaction on a business trip has tested positive to COVID-19, with the measures put in place to ensure accountability of the bringing the countrywide total to 76. Story page 2 funds under the ministry of health, leading to a strong verbal exchange between the two Cabinet ministers. In a statement released, Thursday, Yamba guided that all government entities must submit income and expenditure returns on all COVID-19 funds ECZ sets June 9 received from the Treasury by 5th of every month to the Office of the Accountant General. Story page 5 for by elections By Ulande Nkomesha THE Electoral Commission of Zambia (ECZ) has set June 9 polling day for the Nakato and Imalyo wards in Mongu and Bulilo wards in Chilubi. -

Newsletter Official Publication of the Auditor General’S Office January - March 2014

OAG Republic of Zambia AnNewsletter Official Publication of the Auditor General’s Office January - March 2014 OAG STRATEGISES FOR 2014 IN STYLE ……AS KEY STAKEHOLDERS GRACE THEIR PLANNING MEETING • AUDITOR GENERAL RECEIVES GORDON AMATENDE AWARD • AUDITOR GENERAL RELEASES TWO REPORTS • DAG AUDITS UNDERTAKES FAMILIARISATION TOUR TO Inside this Issue PROVINCIAL AUDIT OFFICES OAG Newsletter | January - March 2014 1 CONTENTS Foreword OAG STRATEGISES FOR 2014 IN STYLE 3 t is with great pleasure that I Iwelcome you all to the January AUDITOR GENERAL RECEIVES GORDON AMATENDE to March publication of the OAG AWARD 4 News for 2014. May I also wish you a happy 2014 AUDITOR GENERAL RELEASES and I hope we shall all do our best TWO REPORTS 4 to serve mother Zambia. Last year is gone and we look forward DAG AUDITS UNDERTAKES FAMILIARISATION TOUR to a fruitful 2014. TO PROVINCIAL AUDIT OFFICES 5 Our OAG News is there to PAC BREATHES FIRE ON MINISTRY share with you what we do and OF GENDER FOR MISAPPLYING WOMEN keep you enlightened on other EMPOWERMENT FUNDS 6 activities carried out during the periods under review. the 2012 Audit report among others. PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE GRILLS FOREIGN This quarter we bring to you We also have a continuation of the AFFAIRS PS 6 articles on the release of my article on decentralization, a satire on reports on the accounts of the Team Building Turns Sour just to bring a MINISTRY OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN ALLOWANCES Republic for the financial year bit of humour to the publication and the SCAM 7 ended 31st December 2012 and gospel to encourage us. -

Members of the Northern Rhodesia Legislative Council and National Assembly of Zambia, 1924-2021

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF ZAMBIA Parliament Buildings P.O Box 31299 Lusaka www.parliament.gov.zm MEMBERS OF THE NORTHERN RHODESIA LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL AND NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF ZAMBIA, 1924-2021 FIRST EDITION, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................................ 3 PREFACE ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................................... 5 ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 9 PART A: MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL, 1924 - 1964 ............................................... 10 PRIME MINISTERS OF THE FEDERATION OF RHODESIA .......................................................... 12 GOVERNORS OF NORTHERN RHODESIA AND PRESIDING OFFICERS OF THE LEGISTRATIVE COUNCIL (LEGICO) ............................................................................................... 13 SPEAKERS OF THE LEGISTRATIVE COUNCIL (LEGICO) - 1948 TO 1964 ................................. 16 DEPUTY SPEAKERS OF THE LEGICO 1948 TO 1964 .................................................................... -

Heads Roll As Police Command Fights Corruption

No322 K10 www.diggers.news Wednesday December 5, 2018 200 COPS CUT FROM TRAFFIC Heads roll as Police Command By Mirriam Chabala Head quarters, 39 at Lusaka Division The Police Command has directed the and 14 in Central Province. Others are transfer of over 200 officers across the 42 from the Ndola Traffic section on the country from the traffic section to general Copperbelt Province while 39 are from duties with immediate effect. Kitwe, 18 from Luanshya district and nine The affected officers include 30 at Service from Chingola among others. fights corruption To page 4 Lungu will go on another vacation soon, says Amos By Zondiwe Mbewe reshuffles to his Cabinet, saying an impromptu ZNBC Special President Edgar Lungu’s it’s still intact. Interview programme, Special Assistant for Press Chanda was peaking during Tuesday,. To page 10 and Public Relations Amos Chanda says the Head of State can be within Zambia but still designate another person to act Kawandami proves govt on his behalf. And Chanda has revealed wrong, shows receipt of that President Lungu will take another vacation within this festive season, but hastened to payment for furniture add that he is well. By Sipilisiwe Ncube Meanwhile, Chanda has The Ministry of Works and Supply has angered former Felix Mutati’s MMD national secretary Raphael Nakacinda delivers his maiden speech to dispelled rumours that Traditional Affairs minister Susan Kawandami for alleging Parliament after President Edgar Lungu nominated him MP - Picture by Kanchele Kanche President Lungu has made that she was owing government for furniture. To page 10 We’ve had enough of PF - Chipimo Mwenya Musenge loses Kafue PF By Mirriam Chabala enough of President Lungu and the PF. -

2018 Economist Intelligence Unit Country Report for Zambia

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Country Report Zambia Generated on February 6th 2018 Economist Intelligence Unit 20 Cabot Square London E14 4QW United Kingdom _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit is a specialist publisher serving companies establishing and managing operations across national borders. For 60 years it has been a source of information on business developments, economic and political trends, government regulations and corporate practice worldwide. The Economist Intelligence Unit delivers its information in four ways: through its digital portfolio, where the latest analysis is updated daily; through printed subscription products ranging from newsletters to annual reference works; through research reports; and by organising seminars and presentations. The firm is a member of The Economist Group. London New York The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit 20 Cabot Square The Economist Group London 750 Third Avenue E14 4QW 5th Floor United Kingdom New York, NY 10017, US Tel: +44 (0) 20 7576 8181 Tel: +1 212 541 0500 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7576 8476 Fax: +1 212 586 0248 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Hong Kong Geneva The Economist Intelligence Unit The Economist Intelligence Unit 1301 Cityplaza Four Rue de l’Athénée 32 12 Taikoo Wan Road 1206 Geneva Taikoo Shing Switzerland Hong Kong Tel: +852 2585 3888 Tel: +41 22 566 24 70 Fax: +852 2802 7638 Fax: +41 22 346 93 47 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] This report can be accessed electronically as soon as it is published by visiting store.eiu.com or by contacting a local sales representative. -

Ficha País De Zambia

OFICINA DE INFORMACIÓN DIPLOMÁTICA FICHA PAÍS Zambia República de Zambia La Oficina de Información Diplomática del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores, Unión Europea y Cooperación pone a disposición de los profesionales de los medios de comunicación y del público en general la presente ficha país. La información contenida en esta ficha país es pública y se ha extraído de diversos medios, no defendiendo posición política alguna ni de este Ministerio ni del Gobierno de España respecto del país sobre el que versa. ABRIL 2021 Forma de Estado: República presidencialista. Zambia División Administrativa: Zambia está organizada territorialmente en 10 pro- vincias: Central, Copperbelt, Este, Luapula, Lusaka, Muchinga, Norte, No- roeste, Sur y Oeste. Cada una de ellas cuenta con la figura de un viceminis- tro, que actúa como Gobernador. Nº residentes españoles: 31 (31/01/2021) Día Nacional: 24 de octubre. Mpulungu Año Independencia: 1964 (24 de octubre de 1964, fecha de su indepen- REPÚBLICA DEMOCRÁTICA TANZANIA dencia de Reino Unido). Kasama DEL CONGO Gentilicio : Zambiano, -na; zambianos, -nas (RAE). Lago 1.2. Geografía Kansanshi Malawi Mufulirá Kitwe Ndola La mayor parte de su superficie se encuentra en una llanura de entre 1.000 y ANGOLA MALAWI Kapiri Mposhi 1.500 m de altura respecto del nivel del mar, al que Zambia no tiene acceso. Kabwe El punto orográfico más elevado (2.200 m) son las Montañas Muchinga, en el MOZAMBIQUE Mongu LUSAKA este del país. Las Cataratas Victoria y el Río Zambeze comparten frontera con Zimbabue. 1.3. Indicadores sociales NAMIBIA ZIMBABUE BOTSUANA Densidad de población: 23,3 habitantes/km² (2020) © Ocina de Información Diplomática. -

Zambia Edalina Rodrigues Sanches Zambia Became Increasingly

Zambia Edalina Rodrigues Sanches Zambia became increasingly authoritarian under Patriotic Front (PF) President Edgar Lungu, who had been elected in a tightly contested presidential election in 2016. The runner-up, the United Party for National Development (UPND), engaged in a series of actions to challenge the validity of the results. The UPND saw 48 of its legislators suspended for boycotting Lungu’s state of the nation address and its leader, Hakainde Hichilema, was arrested on charges of treason after his motorcade allegedly blocked Lungu’s convoy. Independent media and civil society organisations were under pressure. A state of emergency was declared after several arson attacks. Lungu announced his intention to run in the 2021 elections and warned judges that blocking this would plunge the country into chaos. The economy performed better, underpinned by global economic recovery and higher demand for copper, the country’s key export. Stronger performance in the agricultural and mining sectors and higher electricity generation also contributed to the recovery. The Zambian kwacha stabilised against the dollar and inflation stood within the target. The cost of living increased. The country’s high risk of debt distress led the IMF to put off a $ 1.3 bn loan deal. China continued to play a pivotal role in Zambia’s economic development trajectory. New bilateral cooperation agreements were signed with Southern African countries. Domestic Politics The controversial results of the August 2016 presidential elections heightened political tensions for most of the year. Hakainde Hichilema, the UPND presidential candidate since 2006, saw the PF incumbent Lungu win the election by a narrow margin and subsequently contested the results, alleging that the vote was rigged.