Francisco Suárez and the Complexities of Modernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHAT IS TRINITY SUNDAY? Trinity Sunday Is the First Sunday After Pentecost in the Western Christian Liturgical Calendar, and Pentecost Sunday in Eastern Christianity

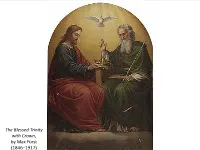

The Blessed Trinity with Crown, by Max Fürst (1846–1917) Welcome to OUR 15th VIRTUAL GSP class! Trinity Sunday and the Triune God WHAT IS IT? WHY IS IT? Presented by Charles E.Dickson,Ph.D. First Sunday after Pentecost: Trinity Sunday Almighty and everlasting God, who hast given unto us thy servants grace, by the confession of a true faith, to acknowledge the glory of the eternal Trinity, and in the power of the Divine Majesty to worship the Unity: We beseech thee that thou wouldest keep us steadfast in this faith and worship, and bring us at last to see thee in thy one and eternal glory, O Father; who with the Son and the Holy Spirit livest and reignest, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. WHAT IS THE ORIGIN OF THIS COLLECT? This collect, found in the first Book of Common Prayer, derives from a little sacramentary of votive Masses for the private devotion of priests prepared by Alcuin of York (c.735-804), a major contributor to the Carolingian Renaissance. It is similar to proper prefaces found in the 8th-century Gelasian and 10th- century Gregorian Sacramentaries. Gelasian Sacramentary WHAT IS TRINITY SUNDAY? Trinity Sunday is the first Sunday after Pentecost in the Western Christian liturgical calendar, and Pentecost Sunday in Eastern Christianity. It is eight weeks after Easter Sunday. The earliest possible date is 17 May and the latest possible date is 20 June. In 2021 it occurs on 30 May. One of the seven principal church year feasts (BCP, p. 15), Trinity Sunday celebrates the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, the three Persons of God: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, “the one and equal glory” of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, “in Trinity of Persons and in Unity of Being” (BCP, p. -

Jesuit Psychology and the Theory of Knowledge

Chapter 5 Jesuit Psychology and the Theory of Knowledge Daniel Heider 1 Introduction Although Jesuit philosophical psychology of the sixteenth and the first decades of the seventeenth century was mostly united against secular Aristotelianism, exemplified by “the sects” of the Alexandrists and the Averroists, doctrinal vari- ety conflating the panoply of Scholastic streams with important ingredients of the neo-Platonic and medical tradition can be seen as a typical feature of the early Jesuits’ philosophical syncretism.1 Despite this doctrinal heterogeneity, the goal of this chapter is to propose what I regard as an important “paradigm shift” in the development of the early (Iberian) Jesuits’ psychology. It has been claimed that Jesuit philosophers of the third generation, such as Pedro Hurta- do de Mendoza (1578–1641), Rodrigo de Arriaga (1592–1667), and Francisco de Oviedo (1602–51), substantially revived the Scholastic via moderna.2 This histo- riographical hypothesis about the crucial role of late medieval nominalism— there are, as yet, very few studies on the matter—will be verified on two issues typical of the period, both of which can be viewed as variants of the classical problem of “the one and the many.” First, there is the query about the char- acter of the distinction between the soul (the principle of unity) and its vital powers (the principle of plurality). Famously, critiques of the Scholastic theory of really distinct accidents (i.e., powers interceding between the soul and its acts; henceforth, the real distinction thesis [rdt]) constituted a representative piece of the philosophical agenda for early modern philosophers in general.3 1 For Jesuit syncretism, see Daniel Heider, “Introduction,” in Cognitive Psychology in Early Jesuit Scholasticism, ed. -

Review Jerome W. Berryman, Children and the Theologians

Review Jerome W. Berryman, Children and the Theologians: Clearing the Way for Grace (New York: Morehouse, 2009). 276 pages. $35. Reviewer: John Wall [email protected] Though the theological study of children has come a long way in recent years, it still occupies a sequestered realm within larger theological inquiry. While no church leader or theologian today can fail to consider issues of gender, race, ethnicity, or culture, the same cannot be said for age. Jerome Berryman’s Children and the Theologians: Clearing the Way for Grace Journal of Childhood and Religion Volume 1 (2010) ©Sopher Press (contact [email protected]) Page 1 of 5 takes a major step toward including children in how the very basics of theology are done. This step is to show that both real children and ideas of childhood have consistently influenced thought and practice in one way or another throughout Christian history, and that they can and should do so in creative ways again today. Berryman, the famed inventor of the children’s spiritual practice of godly play, now extends his wisdom and experience concerning children into a deeply contemplative argument that children are sacramental “means of grace.” The great majority of Children and the Theologians is a patient guide through the lives and writings of at least twenty-five important historical theologians. The reader is led chapter by chapter through the gospels, early theology, Latin theology, the Reformation, early modernity, late modernity, and today. Each chapter opens with the discussion of a work or works of art. Theologians include those with better known ideas on children such as Jesus, Paul, Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, John Calvin, Friedrich Schleiermacher, and Karl Rahner; and some less often thought about in relation to children such as Irenaeus, Anselm, Richard Hooker, Blaise Pascal, and Rowan Williams. -

Revisiting the Franciscan Doctrine of Christ

Theological Studies 64 (2003) REVISITING THE FRANCISCAN DOCTRINE OF CHRIST ILIA DELIO, O.S.F. [Franciscan theologians posit an integral relation between Incarna- tion and Creation whereby the Incarnation is grounded in the Trin- ity of love. The primacy of Christ as the fundamental reason for the Incarnation underscores a theocentric understanding of Incarnation that widens the meaning of salvation and places it in a cosmic con- tent. The author explores the primacy of Christ both in its historical context and with a contemporary view toward ecology, world reli- gions, and extraterrestrial life, emphasizing the fullness of the mys- tery of Christ.] ARL RAHNER, in his remarkable essay “Christology within an Evolu- K tionary View of the World,” noted that the Scotistic doctrine of Christ has never been objected to by the Church’s magisterium,1 although one might add, it has never been embraced by the Church either. Accord- ing to this doctrine, the basic motive for the Incarnation was, in Rahner’s words, “not the blotting-out of sin but was already the goal of divine freedom even apart from any divine fore-knowledge of freely incurred guilt.”2 Although the doctrine came to full fruition in the writings of the late 13th-century philosopher/theologian John Duns Scotus, the origins of the doctrine in the West can be traced back at least to the 12th century and to the writings of Rupert of Deutz. THE PRIMACY OF CHRIST TRADITION The reason for the Incarnation occupied the minds of medieval thinkers, especially with the rise of Anselm of Canterbury and his satisfaction theory. -

Rahner's Christian Pessimism: a Response to the Sorrow of Aids Paul G

Theological Studies 58(1997) RAHNER'S CHRISTIAN PESSIMISM: A RESPONSE TO THE SORROW OF AIDS PAUL G. CROWLEY, S.J. [Editor's Note: The author suggests that the universal sorrow of AIDS stands as a metaphor for other forms of suffering and raises distinctive theological questions on the meaning of hope, God's involvement in evil, and how God's empathy can be ex perienced in the mystery of disease. As an expression of radical realism and hope, Rahner's theology helps us find in the sorrow of AIDS an opening into the mystery of God.] N ONE OF his novels, Nikos Kazantzakis describes St. Francis of As I sisi asking in prayer what more God might require of him. Francis has already restored San Damiano and given up everything else for God. Yet he is riddled with fear of contact with lepers. He confides to Brother Leo: "Even when Fm far away from them, just hearing the bells they wear to warn passers-by to keep their distance is enough to make me faint"1 God's response to Francis's prayer is precisely what he does not want: Francis is to face his fears and embrace the next leper he sees on the road. Soon he hears the dreaded clank of the leper's bell. Yet Francis moves through his fears, embraces the leper, and even kisses his wounds. Jerome Miller, in his phenomenology of suffering, describes the importance of this scene: Only when he embraced that leper, only when he kissed the very ulcers and stumps he had always found abhorrent, did he experience for the first time that joy which does not come from this world and which he would later identify with the joy of crucifixion itself... -

Ventures in Existential Theology: the Wesleyan Quadrilateral And

VENTURES IN EXISTENTIAL THEOLOGY: THE WESLEYAN QUADRILATERAL AND THE HEIDEGGERIAN LENSES OF JOHN MACQUARRIE, RUDOLF BULTMANN, PAUL TILLICH, AND KARL RAHNER by Hubert Woodson, III Bachelor of Arts in English, 2011 University of Texas at Arlington Arlington, TX Master of Education in Curriculum and Instruction, 2013 University of Texas at Arlington Arlington, TX Master of Theological Studies, 2013 Brite Divinity School, Texas Christian University Fort Worth, TX Master of Arts in English, 2014 University of North Texas Denton, TX Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Brite Divinity School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Theology in History and Theology Fort Worth, TX May 2015 VENTURES IN EXISTENTIAL THEOLOGY: THE WESLEYAN QUADRILATERAL AND THE HEIDEGGERIAN LENSES OF JOHN MACQUARRIE, RUDOLF BULTMANN, PAUL TILLICH, AND KARL RAHNER APPROVED BY THESIS COMMITTEE: Dr. James O. Duke Thesis Director Dr. David J. Gouwens Reader Dr. Jeffrey Williams Associate Dean for Academic Affairs Dr. Joretta Marshall Dean WARNING CONCERNING COPYRIGHT RESTRICTIONS The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish photocopy or reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

Supplementary Anselm-Bibliography 11

SUPPLEMENTARY ANSELM-BIBLIOGRAPHY This bibliography is supplementary to the bibliographies contained in the following previous works of mine: J. Hopkins, A Companion to the Study of St. Anselm. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1972. _________. Anselm of Canterbury: Volume Four: Hermeneutical and Textual Problems in the Complete Treatises of St. Anselm. New York: Mellen Press, 1976. _________. A New, Interpretive Translation of St. Anselm’s Monologion and Proslogion. Minneapolis: Banning Press, 1986. Abulafia, Anna S. “St Anselm and Those Outside the Church,” pp. 11-37 in David Loades and Katherine Walsh, editors, Faith and Identity: Christian Political Experience. Oxford: Blackwell, 1990. Adams, Marilyn M. “Saint Anselm’s Theory of Truth,” Documenti e studi sulla tradizione filosofica medievale, I, 2 (1990), 353-372. _________. “Fides Quaerens Intellectum: St. Anselm’s Method in Philosophical Theology,” Faith and Philosophy, 9 (October, 1992), 409-435. _________. “Praying the Proslogion: Anselm’s Theological Method,” pp. 13-39 in Thomas D. Senor, editor, The Rationality of Belief and the Plurality of Faith. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995. _________. “Satisfying Mercy: St. Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo Reconsidered,” The Modern Schoolman, 72 (January/March, 1995), 91-108. _________. “Elegant Necessity, Prayerful Disputation: Method in Cur Deus Homo,” pp. 367-396 in Paul Gilbert et al., editors, Cur Deus Homo. Rome: Prontificio Ateneo S. Anselmo, 1999. _________. “Romancing the Good: God and the Self according to St. Anselm of Canterbury,” pp. 91-109 in Gareth B. Matthews, editor, The Augustinian Tradition. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999. _________. “Re-reading De Grammatico or Anselm’s Introduction to Aristotle’s Categories,” Documenti e studi sulla tradizione filosofica medievale, XI (2000), 83-112. -

Interpreting Rahner's Metaphoric Logic Robert Masson Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Theology Faculty Research and Publications Theology, Department of 1-1-2010 Interpreting Rahner's Metaphoric Logic Robert Masson Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. Theological Studies, Vol. 71, No. 2 (2010): 380-409. Permalink. © 2010 Theological Studies, Inc. Used with permission. Theological Studies 71 (2010) INTERPRETING RAHNER'S METAPHORIC LOGIC ROBERT MASSON Recent provocative reinterpretations of Karl Rahner's theology illustrate the hermeneutical challenge of retrieving his achievement for a new era. The spectrum of positions is exemplified by Karen Kilby, Patrick Burke, and Philip Endean. The essay proposes an alternative interpretive scheme attentive to Rahner's metaphoric logic. NEW GENERATION OF SCHOLARS is raising fundamental questions Aabout the balance, coherence, and foundations of Rahner's theology. They are bringing new questions and theological contexts to his thought and bringing Rahner's thought to bear on questions that had not been at the center of his attention—if on his horizon at all. While many of his former students and disciples have been content to explain and interpret Rahner in his own terms, this new generation seeks explanatory schemes that are not at all or much less dependent on his own conceptual framework and technical vocabulary. In critically engaging Rahner's texts, they take apparent discontinuities seriously while eschewing both overly generous harmonizations and unsympathetic caricatures. Their readings of Rahner illustrate the hermeneutical challenge of retrieving his achievement for a new theological era. The spectrum of reinterpretations is exemplified by Karen Kilby, Patrick Burke, and Philip Endean.1 Others could be cited, but these three illustrate ROBERT MASSON received his Ph.D. -

Karl Rahner on the Soul

Karl Rahner on the Soul Rev. Terrance W. Klein, S.T.D. Fordham University Karl Rahner rejects the notion that when Christians speak of a soul they are citing a surreptitious citizen of a realm that lies beyond or above science. For Rahner, the purpose of calling the soul the supernatural element of the human person is not to establish two spheres within one human being, but rather to attest to the sheer gratuity of our orientation toward God in Christ. When we use the word “spirit,” we philosophically reference our disposition over and against the world. When we use the word “soul,” we theologically assert the ultimate orientation of this spirit towards God. On Interpretation First, a word about interpretation, which is my task. One of the great Heidegger-inspired insights of twentieth century philosophy is that of the hermeneutical circle. Essentially the notion that we cannot simply seize the insights of another as though these were objects lying ready to hand. Rather, when we try to understand another, we become de facto interpreters, because we can’t help but approach the other in the light of our own preunderstanding. Hence, one cannot hope to approach a text without prejudice, which is always present. What one can do is to try to expose one’s own preunderstanding, so that, brought to light, its engagement with the text can be seen for what it is, a starting place in what is ultimately a conversation with the author. Gadamer taught us that what ultimately makes the conversation a fruitful dialogue, rather than a rapacious misreading, is a common tradition, the mutual questions and concerns that both the author and the interpreter share. -

Orthopraxis and the Theologian Bernard J

Theological Studies 49 (1988) ON DOING THE TRUTH: ORTHOPRAXIS AND THE THEOLOGIAN BERNARD J. VERKAMP Vincennes University, Vincennes, Ind. NE HOT spring day, some 15 years ago, I was sitting in my St. Louis O apartment working on an especially murky segment of the history of adiaphorism (the 1550 Vestiarian Dispute), when I heard sounds of an angry crowd congregating in front of the Saint Louis University ROTC building, which then stood directly across the street from my apartment. The evening before, I had taken time out from my studies to accompany some friends to an anti-Vietnam War rally on campus, and as the students' cries of protest now drifted up to my third-floor apartment, I was again distracted enough to drop what I was doing and go to the window. I got there just in time to see some 25 policemen emerging from the ROTC building and beating back some of the more aggressive protestors. Although I abhorred the violence that had earlier resulted in the burning down of the Washington University ROTC building across town, my sympathies were basically with the students, and as I watched their protest, I was strongly tempted to go down to the street and make a stand alongside them. But after cheering them on for a few moments from my window perch, I returned instead to my books and Bishop Hooper's rather obtuse line of argument against the wearing of a surplice. There were other occasions when I was not so successful in resisting the temptation to get involved in the current praxis or to take sides. -

SECOND SCHOLASTICISM and BLACK SLAVERY1 Segunda Escolástica E Escravidão Negra La Segunda Escolástica Y La Esclavitud Negra

PORTO ALEGRE http://dx.doi.org/10.15448/1984-6746.2019.3.36112 SECOND SCHOLASTICISM AND BLACK SLAVERY1 Segunda Escolástica e escravidão negra La Segunda Escolástica y la esclavitud negra Roberto Hofmeister Pich2 Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil Abstract In order to systematically explore the normative treatment of black slavery by Second Scholastic thinkers, usually placing the problem within the broad discussion of moral conscience and, more narrowly, the nature and justice of trade and contracts, I propose two stations of research that may be helpful for future studies, especially in what con- cerns the study of Scholastic ideas in colonial Latin America. Beginning with the analysis of just titles for slavery and slavery trade proposed by Luis de Molina S.J. (1535–1600), I show how his accounts were critically reviewed by Diego de Avendaño S.J. (1594–1688), revealing basic features of Second Scholastic normative thinking in Europe and the Americas. Normative knowledge provided by these two Scholastic intellectuals would be deeply tested throughout the last decades of the 17th century, especially by authors who sharpened the systemic analysis and a rigorist moral assessment of every title of slavery and slaveholding, as well as the requirements of an ethics of restitution. Keywords: black slavery, Second Scholasticism, commutative justice, probabilism, Luis de Molina, Diego de Avendaño. 1 This study was prepared during a stay as guest professor at the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms- Universität Bonn / Germany, as first “CAPES / Universität Bonn Lehrstuhlinhaber”, from July 2018 to February 2019. I hereby express my gratitude to the remarkable support of the Brazilian Agency Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel) and the University of Bonn. -

Truth and Truthmaking in 17Th-Century Scholasticism

Truth and Truthmaking in 17th-Century Scholasticism by Brian Embry A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy University of Toronto © Copyright by Brian Embry 2015 Truth and Truthmaking in 17th-Century Scholasticism Brian Embry Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy University of Toronto 2015 Abstract Some propositions are true and others are false. What explains this difference? Some philosophers have recently defended the view that a proposition is true because there is an entity, its truthmaker, that makes it true. Call this the ‘truthmaker principle’. The truthmaker principle is controversial, occasioning the rise of a large contemporary debate about the nature of truthmaking and truthmakers. What has gone largely unnoticed is that scholastics of the early modern period also had the notion of a truthmaker [verificativum], and this notion is at the center of early modern scholastic disputes about the ontological status of negative entities, the past and future, and uninstantiated essences. My project is to explain how early modern scholastics conceive of truthmaking and to show how they use the notion of a truthmaker to regiment ontological enquiry. I argue that the notion of a truthmaker is born of a certain conception of truth according to which truth is a mereological sum of a true mental sentence and its intentional object. This view entails the truthmaker principle and is responsible for some surprising metaphysical views. For example, it leads many early modern scholastics to posit irreducible negative entities as truthmakers for negative truths, giving rise to an extensive literature on the nature of negative entities.