Ventures in Existential Theology: the Wesleyan Quadrilateral And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHAT IS TRINITY SUNDAY? Trinity Sunday Is the First Sunday After Pentecost in the Western Christian Liturgical Calendar, and Pentecost Sunday in Eastern Christianity

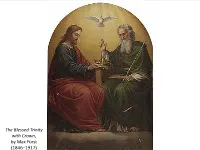

The Blessed Trinity with Crown, by Max Fürst (1846–1917) Welcome to OUR 15th VIRTUAL GSP class! Trinity Sunday and the Triune God WHAT IS IT? WHY IS IT? Presented by Charles E.Dickson,Ph.D. First Sunday after Pentecost: Trinity Sunday Almighty and everlasting God, who hast given unto us thy servants grace, by the confession of a true faith, to acknowledge the glory of the eternal Trinity, and in the power of the Divine Majesty to worship the Unity: We beseech thee that thou wouldest keep us steadfast in this faith and worship, and bring us at last to see thee in thy one and eternal glory, O Father; who with the Son and the Holy Spirit livest and reignest, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. WHAT IS THE ORIGIN OF THIS COLLECT? This collect, found in the first Book of Common Prayer, derives from a little sacramentary of votive Masses for the private devotion of priests prepared by Alcuin of York (c.735-804), a major contributor to the Carolingian Renaissance. It is similar to proper prefaces found in the 8th-century Gelasian and 10th- century Gregorian Sacramentaries. Gelasian Sacramentary WHAT IS TRINITY SUNDAY? Trinity Sunday is the first Sunday after Pentecost in the Western Christian liturgical calendar, and Pentecost Sunday in Eastern Christianity. It is eight weeks after Easter Sunday. The earliest possible date is 17 May and the latest possible date is 20 June. In 2021 it occurs on 30 May. One of the seven principal church year feasts (BCP, p. 15), Trinity Sunday celebrates the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, the three Persons of God: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, “the one and equal glory” of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, “in Trinity of Persons and in Unity of Being” (BCP, p. -

Phenomenology As Philosophy and Method Applications to Ways of Doing Special Education

Phenomenology As Philosophy and Method Applications to Ways of Doing Special Education JEAN C. McPHAIL ABSTRACT 1 HENOMENOLOGY IS A PHILOSOPHICAL MOVEMENT The theoretical positions of the preceding two texts THAT APPROACHES THE STUDY OF HUMAN BEINGS AND THEIR create significantly different orientations to the life worlds CULTURE DIFFERENTLY FROM THE LOGICAL POSITIVIST MODEL of people. The quote by Merleau-Ponty describes the USED IN THE NATURAL SCIENCES AND IN SPECIAL EDUCA- essential focus of the phenomenological movement in TION. PHENOMENOLOGISTS VIEW THE APPLICATION OF THE philosophy—human consciousness. The Individualized Edu- LOGICAL POSITIVIST MODEL TO THE STUDY OF HUMAN BEINGS cation Program written for a 13-year-old young man with AS INAPPROPRIATE BECAUSE THE MODEL DOES NOT ADDRESS learning disabilities characterizes the prevalent view of THE UNIQUENESS OF HUMAN LIFE. IN THIS ARTICLE, THE individuals working in the field of special education—an THEORETICAL ASSUMPTIONS AND METHODOLOGICAL orientation directed toward changing the behavior of indi- ORIENTATIONS OF PHENOMENOLOGY ARE DISCUSSED, viduals with disabilities. Whereas phenomenology privi- FOLLOWED BY THEIR APPLICATIONS TO WAYS OF DOING leges the nature of the meanings that people construct in RESEARCH IN SPECIAL EDUCATION. their lives and that guide their actions, special education focuses on the study and practice of behavioral change outside the context of the life meanings of individuals with disabilities. The shift that Bruner (1990) described in the early stages of the cognitive revolution from an emphasis on the "construction of meaning to the processing of mean- P. HENOMENOLOGY IS AN INVENTORY OF CON- ing" (p. 4) aptly characterizes the essential differences JLsciousness HEN( as of that wherein a universe resides. -

Vietnamese Existential Philosophy: a Critical Reappraisal

VIETNAMESE EXISTENTIAL PHILOSOPHY: A CRITICAL REAPPRAISAL A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Hi ền Thu Lươ ng May, 2009 i © Copyright 2009 by Hi ền Thu Lươ ng ii ABSTRACT Title: Vietnamese Existential Philosophy: A Critical Reappraisal Lươ ng Thu Hi ền Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2009 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Lewis R. Gordon In this study I present a new understanding of Vietnamese existentialism during the period 1954-1975, the period between the Geneva Accords and the fall of Saigon in 1975. The prevailing view within Vietnam sees Vietnamese existentialism during this period as a morally bankrupt philosophy that is a mere imitation of European versions of existentialism. I argue to the contrary that while Vietnamese existential philosophy and European existentialism share some themes, Vietnamese existentialism during this period is rooted in the particularities of Vietnamese traditional culture and social structures and in the lived experience of Vietnamese people over Vietnam’s 1000-year history of occupation and oppression by foreign forces. I also argue that Vietnamese existentialism is a profoundly moral philosophy, committed to justice in the social and political spheres. Heavily influenced by Vietnamese Buddhism, Vietnamese existential philosophy, I argue, places emphasis on the concept of a non-substantial, relational, and social self and a harmonious and constitutive relation between the self and other. The Vietnamese philosophers argue that oppressions of the mind must be liberated and that social structures that result in violence must be changed. Consistent with these ends Vietnamese existentialism proposes a multi-perspective iii ontology, a dialectical view of human thought, and a method of meditation that releases the mind to be able to understand both the nature of reality as it is and the means to live a moral, politically engaged life. -

Post-Continental Philosophy: Its Definition, Contours, and Fundamental Sources

Post-continental Philosophy: Its Definition, Contours, and Fundamental Sources NELSON MALDONADO-TORRES It is no accident that the global geographical framework in use today is essentially a cartographic celebration of European power. After centuries of imperialism, the presumptions of a worldview of a once-dominant metropole has become part of the intellectual furniture of the world…. Metageography matters, and the attempt to engage it critically has only begun. Martin W. Lewis and Kären W. Wigen, The Myth of Continents.1 or several decades now the contours of legitimate philosophy have been drawn by advocates of F so-called analytic and continental philosophies. Analytic philosophy is often referred to as a style of thinking centered on the question of whether something is true, rather than, as continental philosophy, on the multiple factors that constitute meaning.2 Analytic philosophy is also said to be closer to the sciences, while continental philosophy has more affinity with the humanities.3 One of the reasons for this lies in that while analytic philosophy tends to dismiss history from its reflections, continental philosophy typically emphasizes the relevance of time, tradition, lived experience, and/or social context. Fortunately, this situation is slowly but gradually changing today. A variety of intellectuals are defying the rigid boundaries of these fields. Some of the most notable are Afro- American, Afro-Caribbean, and Latina/o scholars using the arsenal of these bodies of thought to analyze and interpret problems related to colonialism, racism, and sexism in the contemporary world.4 These challenges demand a critical analysis of the possibilities and limits of change within the main coordinates of these different styles or forms of philosophizing. -

Ingolf U. Dalferth Varieties of Philosophical Theology Before and After Kant

Ingolf U. Dalferth Varieties of Philosophical Theology Before and After Kant 1. Prehistory, History, and Posthistory of Philosophical Theology Philosophical theology (PT),1 which replaced natural and rational theology after Kant, began its modern career as a distinct philosophical project, based not on faith and religion but on reason and reflection and/or nature, experience, and science. However, it has never been a monolithic endeavour, and its impact on Christian thinking has been constructive as well as critical or even destructive. Its prehistory that is sometimes mistakenly taken to be part of it includes such diverse factors as Platonist dualism, the Aristotelian pattern of causality, Stoic immanentism, Philonean personalism, Neoplatonist negative theology and Sozinian antitrinitarian- ism. From its most ancient roots the theology of the philosophers in the Western tradition was intimately bound up with the rise of reason and science in ancient Greece. When the gods ceased to be part of the furniture of the world, God (the divine) became an explanatory principle based not on the traditional mythological tales but on cosmo- logical science, astronomical speculation, and metaphysical reflection. Its idea of God involved the ideas of divine singularity (there is only one God), of divine transcendence (God is neither part nor the whole of the world) and of divine immanence (God’s active presence can be discerned in the order, regularity, and beauty of the cosmos). And even though it took a long time to grasp those differences clearly, the monotheistic difference between gods and God, the cosmological difference between God and the world, and the metaphysical difference between the transcendence and immanence of God have remained central to the intellectual enterprise of theological reflection in philosophy. -

James H. Cone: Father of Contemporary Black Theology

James H. Cone: Father Of Contemporary Black Theology RUFUS BURROW, JR. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this article is to provide pastors, laypersons, students and aca- demicians with a sense of the human being behind and in the thick of black lib- eration theology as well as his courage to both lead and change. I shall briefly discuss aspects of James Hal Cone's background, some early frustrations and challenges he confronted, and ways in which his theology has shifted. Since the late 1960s, Cone has been among the most creative and courageous of the contemporary black liberation theologians. Although he has been writing major theologi"tal treatises since 1968, there has been no booklength manuscript published on his work. There have, however, been a number of dissertations written on his theology since 1974, some of which are comparative studies. Cone has been the subject of much criticism by white theologians, although few of them have taken either him or the black religious experience seriously enough to be willing to devote the time and energy necessary to learn all they can about these in order to engage in intelligent dialogue and criticism. Considered the premier black theologian and the "father of contemporary black theology," it is strange that after more than twenty years of writing, lectur- ing on and doing black theology, no one has yet devoted a book to Cone's work.' To be sure, Cone's is not the only version of black liberation theology. However, it was he who introduced this new way of doing theology in a systematic way. -

Continental Philosophies of the Social Sciences David Teira

Continental philosophies of the social sciences David Teira 1. Introduction In my view, there is no such thing as a continental philosophy of the social sciences. There is, at least, no consensual definition of what is precisely continental in any philosophical approach. 1 Besides, there are many approaches in the philosophy of the social sciences that are often qualified as continental , but there is no obvious connection between them. The most systematic attempt so far to find one is Yvonne Sherratt’s (2006) monograph, where continental approaches would be appraised as different branches of the Humanist tradition. According to Sherratt, philosophers in this tradition draw on the ideas and arguments of the ancient Greek and Roman thinkers, since they understand philosophy as an accumulative endeavor, where the past is a continuous source of wisdom. Unlike empiricist philosophers in the analytic tradition, humanists see the world as an intrinsically purpose-laden, ethically, aesthetically, and spiritually valuable entity . However, once you adopt such a broad definition in order to encompass such different thinkers as Marx, Nietzsche, Heidegger or Foucault, it seems difficult not to see humanistic traits in analytic philosophers as well. Moreover, when it comes to the philosophical study of actual social sciences, it is not clear whether adopting a humanistic stance makes, as such, any difference in the analysis: as we will see below, the arguments of the continental philosophers discussed here do not presuppose a particular commitment with, e.g., ideas from classical Antiquity. Certain Greeks named those who did not speak their language Barbarians , but it was never clear who counted as a proper speaker of Greek. -

Ministering to the Mourning.3Rd Pf 3/1/06 8:46 AM Page 7

Ministering to the Mourning.3rd pf 3/1/06 8:46 AM Page 7 Contents Preface 9 Foreword 11 1. Death and Contemporary American Culture 13 2. Death in the Old Testament 23 3. Death in the New Testament 37 4. Death and the Physician 55 5. Death and the Christian Caregiver 65 6. Death and the Funeral Director 79 7. Death and the Family: The Pastoral Opportunity 89 8. Death and the Final Good-Bye 107 9. Challenging Situations 129 10. Questions Pastors and Mourners Ask 155 11. An Anthology of Resources 177 Appendix—Ideas for Funeral Messages 191 Bibliography 203 Scripture Index 225 About the Authors 237 Ministering to the Mourning.3rd pf 3/1/06 8:39 AM Page 13 ONE Death and Contemporary American Culture It’s becoming more and more difficult to minister to grieving people, because in their attempts to enjoy life, many of them are denying death. Mention death and the average person responds something like comedian Woody Allen: “It’s not that I’m afraid to die. I just don’t want to be there when it happens.” There are no funeral homes in shopping malls to remind us of our mortality; and if there were, the salespeople would have to hand out free coffee to keep shoppers from looking the other way. With one hand gripping the steering wheel and the other holding a cell phone, most people breeze their way through the day and never consider that it might be their last. Ours is a culture that insists that we remain young, no matter how old we are. -

PHI 516/GER 566/REL 516 Special Topics In

PHI 516/GER 566/REL 516 Special Topics in History of Phil: Knowledge & Belief in Kant, Fichte, Hegel Instructor: Andrew Chignell ([email protected]) Spring 2020, Marx 201, Th 1:30-4:20 Office: 232 1879 Hall; Office Hours: Tues 4-5:30 and by appt A seminar on Kantian epistemology and pistology (the theory of faith or acceptance). Topics include: the nature and ethics of assent (holding-for-true); the nature of knowledge; fallibilism and infallibilism about epistemic justification; cognition and spontaneity; noumenal ignorance; opinion and common sense; epistemic autonomy; and the structure of practical arguments, both pragmatic and moral. In the final weeks of the seminar we will consider how some of these themes are treated by two of Kant’s most influential successors – J.G. Fichte and G.W.F. Hegel. Along the way, we will look at some broadly Kantian efforts in contemporary epistemology by authors like Mark Schroeder and Kurt Sylvan. Assignments: 1. Short reflections: Everyone taking the course for credit is asked to submit five 1-2 page reflections. Often these will simply elaborate a question about the reading, but they can also involve criticism or constructive work. These are due on Wednesday night before class at 11.59pm, and should focus on the readings for the following day’s class. Graded on a satisfactory/unsatisfactory basis, they are worth (combined) 30% of the grade. As long as you’re doing the required reading, it shouldn’t be hard to achieve full credit for this. 2. Presentation: Ph.D. students have the opportunity (but not the obligation) to give a short presentation to the seminar. -

Preliminary Conclusions in the Search of Philosophical Grounds for Contemporary Unitarian Identity

Preliminary Conclusions in the Search of Philosophical Grounds for Contemporary Unitarian Identity By Neville Buch The Unitarian denomination itself always remained small, of course, but the Harvard moralists had resigned themselves to this very early. “Our object is not to convert men to our party, but to our principles,” they declared. “Unitarians have done more…by promoting a real though gradual change for the better in the opinions of other sects, than by building up their own denomination”. [Daniel Walker Howe. The Unitarian Consciencei] Whether it be Utilitarianism or Unitarianism, [William] James argued in 1868, the philosopher’s role includes not only crystallizing the doctrine but also presenting it in the most persuasive light to the populace. [Gerald E. Myers. William James: His Life and Thought ii]. William James remark on the philosopher’s role in a letter to Oliver Wendell Holmes in 1868 is a direct challenge to a disempowering attitude that has unfortunately prevailed in Unitarianism since the remark of James Walker in 1830 as quoted by Daniel Howe above. The disempowering attitude is unfortunate because it can be shown that its own advocacy is eroded by an apparent meaninglessness when clear preciseness is demanded. To deconstruct Walker’s statement -- what has been overlooked is that ‘our party’ and ‘our principles’ are related in an inseparable Unitarian identity. “Our party” is the Unitarian body. “Our principles” are Unitarian principles, that is, principles belonging to the Unitarian body. They are principles marked out as Unitarian because Unitarians have claimed them as their own. The philosophical reasons for this claim are not yet apparent. -

The Etienne Gilson Series 21

The Etienne Gilson Series 21 Remapping Scholasticism by MARCIA L. COLISH 3 March 2000 Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies This lecture and its publication was made possible through the generous bequest of the late Charles J. Sullivan (1914-1999) Note: the author may be contacted at: Department of History Oberlin College Oberlin OH USA 44074 ISSN 0-708-319X ISBN 0-88844-721-3 © 2000 by Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies 59 Queen’s Park Crescent East Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 2C4 Printed in Canada nce upon a time there were two competing story-lines for medieval intellectual history, each writing a major role for scholasticism into its script. Although these story-lines were O created independently and reflected different concerns, they sometimes overlapped and gave each other aid and comfort. Both exerted considerable influence on the way historians of medieval speculative thought conceptualized their subject in the first half of the twentieth cen- tury. Both versions of the map drawn by these two sets of cartographers illustrated what Wallace K. Ferguson later described as “the revolt of the medievalists.”1 One was confined largely to the academy and appealed to a wide variety of medievalists, while the other had a somewhat narrower draw and reflected political and confessional, as well as academic, concerns. The first was the anti-Burckhardtian effort to push Renaissance humanism, understood as combining a knowledge and love of the classics with “the discovery of the world and of man,” back into the Middle Ages. The second was inspired by the neo-Thomist revival launched by Pope Leo XIII, and was inhabited almost exclusively by Roman Catholic scholars. -

Review Jerome W. Berryman, Children and the Theologians

Review Jerome W. Berryman, Children and the Theologians: Clearing the Way for Grace (New York: Morehouse, 2009). 276 pages. $35. Reviewer: John Wall [email protected] Though the theological study of children has come a long way in recent years, it still occupies a sequestered realm within larger theological inquiry. While no church leader or theologian today can fail to consider issues of gender, race, ethnicity, or culture, the same cannot be said for age. Jerome Berryman’s Children and the Theologians: Clearing the Way for Grace Journal of Childhood and Religion Volume 1 (2010) ©Sopher Press (contact [email protected]) Page 1 of 5 takes a major step toward including children in how the very basics of theology are done. This step is to show that both real children and ideas of childhood have consistently influenced thought and practice in one way or another throughout Christian history, and that they can and should do so in creative ways again today. Berryman, the famed inventor of the children’s spiritual practice of godly play, now extends his wisdom and experience concerning children into a deeply contemplative argument that children are sacramental “means of grace.” The great majority of Children and the Theologians is a patient guide through the lives and writings of at least twenty-five important historical theologians. The reader is led chapter by chapter through the gospels, early theology, Latin theology, the Reformation, early modernity, late modernity, and today. Each chapter opens with the discussion of a work or works of art. Theologians include those with better known ideas on children such as Jesus, Paul, Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, John Calvin, Friedrich Schleiermacher, and Karl Rahner; and some less often thought about in relation to children such as Irenaeus, Anselm, Richard Hooker, Blaise Pascal, and Rowan Williams.