'Religious Experience' for Catholic-Pentecosotal Dialogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHAT IS TRINITY SUNDAY? Trinity Sunday Is the First Sunday After Pentecost in the Western Christian Liturgical Calendar, and Pentecost Sunday in Eastern Christianity

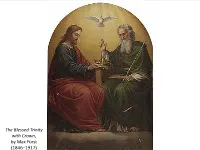

The Blessed Trinity with Crown, by Max Fürst (1846–1917) Welcome to OUR 15th VIRTUAL GSP class! Trinity Sunday and the Triune God WHAT IS IT? WHY IS IT? Presented by Charles E.Dickson,Ph.D. First Sunday after Pentecost: Trinity Sunday Almighty and everlasting God, who hast given unto us thy servants grace, by the confession of a true faith, to acknowledge the glory of the eternal Trinity, and in the power of the Divine Majesty to worship the Unity: We beseech thee that thou wouldest keep us steadfast in this faith and worship, and bring us at last to see thee in thy one and eternal glory, O Father; who with the Son and the Holy Spirit livest and reignest, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. WHAT IS THE ORIGIN OF THIS COLLECT? This collect, found in the first Book of Common Prayer, derives from a little sacramentary of votive Masses for the private devotion of priests prepared by Alcuin of York (c.735-804), a major contributor to the Carolingian Renaissance. It is similar to proper prefaces found in the 8th-century Gelasian and 10th- century Gregorian Sacramentaries. Gelasian Sacramentary WHAT IS TRINITY SUNDAY? Trinity Sunday is the first Sunday after Pentecost in the Western Christian liturgical calendar, and Pentecost Sunday in Eastern Christianity. It is eight weeks after Easter Sunday. The earliest possible date is 17 May and the latest possible date is 20 June. In 2021 it occurs on 30 May. One of the seven principal church year feasts (BCP, p. 15), Trinity Sunday celebrates the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, the three Persons of God: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, “the one and equal glory” of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, “in Trinity of Persons and in Unity of Being” (BCP, p. -

A Catholic-Indigenous Spiritual Dialogue, on Religious Experience and Creation

A Catholic-Indigenous Spiritual Dialogue, On Religious Experience and Creation Submitted by: Paul Robson S.J. April, 2017 Saint Paul University, Ottawa Research supervisor: Achiel Peelman O.M.I. Paper # 1 of 2 Submitted to complete the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Theology © Paul Robson S.J., Ottawa, Canada, 2017 Special thanks to: Achiel, Cle-alls (John Kelly), my Dad, Eric Jensen S.J., and the Ottawa Jesuit community Robson ii Table of contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Section 1: Interreligious dialogue ………………………………………………………………………………… 8 Section 2: Ignatius of Loyola and Basil Johnston ………………………………………………………… 22 Section 3: Cle-alls’ and my own reflections ………………………………………………………………… 41 Section 4: A glance through Church history ……………………………………………………………….. 57 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 65 Bibliography ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 68 Robson iii Introduction We humans, and our planet, are facing an ecological crisis. Scientists have asserted that the planet Earth is moving toward a mass extinction of species, with this catastrophic event be- ing different from past mass extinctions on this planet in that this one will have been caused by human activity.1 There is reason for hope, though, as this future eventuality has been referred to as “still-avoidable”.2 How might we avoid this looming calamity? Pope Francis has argued the following, related to dealing with the ecological crisis: Ecological culture cannot be reduced to a series of urgent -

How Can Spirituality Be Marian? Johann G

Marian Studies Volume 52 The Marian Dimension of Christian Article 5 Spirituality, Historical Perspectives, I. The Early Period 2001 How Can Spirituality be Marian? Johann G. Roten University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies Recommended Citation Roten, Johann G. (2001) "How Can Spirituality be Marian?," Marian Studies: Vol. 52, Article 5. Available at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies/vol52/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Studies by an authorized editor of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Roten: Spirituality Spirituality HOW CAN SPIRITUALITY BE MARIAN? Johann G. Roten, S.M.* "There is nothing better than true devotion to Mary, con, ceived as an ever more complete following of her example, to in, troduce one to the joy ofbelieving."1 Can this statement, formu, lated with the spiritual formation of future priests in mind, be applied to all Christians? Is it true that sound Marian devotion is "an essential aspect of Christian spirituality"F Or must we con, cede that Marina Warner's prophecy has come true, namely, that the "reality of her [Mary's] myth is over; the moral code sheaf, firms has been exhausted"?3 While reducing Marian devotion to an expression of the "traditionalist counter,movement," a recent sociological study reached a different conclusion: "With the weight of the history I reviewed ... firmly supporting the following con, elusion, I contend that Marian devotion will continue well into the next millennium. -

Dominican Spirituality

OurLadyoftheHolyRosaryProvince,OP DOMINICAN SPIRITUALITY Principles and Practice By WILLIAM A. HINNEBUSCH, O.P. Illustrations by SISTER MARY OF THE COMPASSION, O.P. http://www.domcentral.org/trad/domspirit/default.htm DOMINICANSPIRITUALITY 1 OurLadyoftheHolyRosaryProvince,OP FOREWORD Most of this book originated in a series of conferences to the Dominican Sisters of the Congregation of the Most Holy Cross, Amityville, New York, at Dominican Commercial High School, Jamaica, L. I., during the Lent of 1962. All the conferences have been rewritten with some minor deletions and the addition of considerable new material. The first chapter is added as a general introduction to Dominican life to serve as a unifying principle for the rest of the book. I have also adapted the material to the needs of a wider reading audience. No longer do I address the sister but the Dominican. While some matter applies specifically to nuns or sisters, the use of masculine nouns and pronouns elsewhere by no means indicates that I am addressing only the members of the First Order. Though the forms and methods of their spiritual life vary to some degree ( especially that of the secular tertiary), all Dominicans share the same basic vocation and follow the same spiritual path. I must thank the sisters of the Amityville community for their interest in the conferences, the sisters of Dominican Commercial High School for taping and mimeographing them, the fathers and the sisters of other Congregations who suggested that a larger audience might welcome them. I am grateful to the fathers especially of the Dominican House of Studies, Washington, D. -

189 BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES Writings of Saint Francis

189 BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES Writings of Saint Francis A Blessing for Brother Leo The Canticle of the Creatures The First Letter to the Faithful The Second Letter to the Faithful A Letter to the Rulers of the Peoples The Praises of God The Earlier Rule The Later Rule A Rule for Hermitages The Testament True and Perfect Joy Franciscan Sources The Life of Saint Francis by Thomas of Celano The Remembrance of the Desire of a Soul The Mirror of Perfection, Smaller Version The Mirror of Perfection, Larger Version The Sacred Exchange between Saint Francis and Lady Poverty The Anonymous of Perugia The Legend of the Three Companions The Legend of Perugia The Assisi Compilation The Sermons of Bonaventure The Major Legend by Bonaventure The Minor Legend by Bonaventure The Deeds of Saint Francis and His Companions The Little Flowers of Saint Francis The Chronicle of Jordan of Giano Secondary Sources Aristotle. 1953. The works of Aristotle translated into English, Vol.11. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Armstrong, Edward A.1973. Saint Francis : nature mystic : the derivation and significance of the nature stories in the Franciscan legend. Berkeley: University of California Press. Armstrong, Regis J. 1998. At. Francis of Assisi: writings for a Gospel life. NY: Crossroad. Armstrong, R.,Hellmann, JAW., & Short W. 1999. Francis of Assisi: Early documents, The Saint. Vol.1. N Y: New City Press. Armstrong, R,. Hellmann, JAW., & Short, W. 2000. Francis of Assisi: Early documents, The Founder. Vol.2. N Y: New City Press. Armstrong, R., Hellmann, JAW., & Short, W. 2001. Francis of Assisi: Early Documents, The Prophet. -

Don Quixote and Catholicism: Rereading Cervantine Spirituality

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Book Previews Purdue University Press 8-2020 Don Quixote and Catholicism: Rereading Cervantine Spirituality Michael J. McGrath Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_previews Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation McGrath, Michael J., "Don Quixote and Catholicism: Rereading Cervantine Spirituality" (2020). Purdue University Press Book Previews. 59. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_previews/59 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. DON QUIXOTE AND CATHOLICISM Purdue Studies in Romance Literatures Editorial Board Íñigo Sánchez Llama, Series Editors Deborah Houk Schocket Elena Coda Gwen Kirkpatrick Paul B. Dixon Allen G. Wood Patricia Hart Howard Mancing, Consulting Editor Floyd Merrell, Consulting Editor Joyce L. Detzner, Production Editor Associate Editors French Spanish and Spanish American Jeanette Beer Catherine Connor Paul Benhamou Ivy A. Corfis Willard Bohn Frederick A. de Armas Thomas Broden Edward Friedman Gerard J. Brault Charles Ganelin Mary Ann Caws David T. Gies Glyn P. Norton Allan H. Pasco Roberto González Echevarría Gerald Prince David K. Herzberger Roseann Runte Emily Hicks Ursula Tidd Djelal Kadir Italian Amy Kaminsky Fiora A. Bassanese Lucille Kerr Peter Carravetta Howard Mancing Benjamin Lawton Floyd Merrell Franco Masciandaro Alberto Moreiras Anthony Julian Tamburri Randolph D. Pope . Luso-Brazilian Elzbieta Skl-odowska Fred M. Clark Marcia Stephenson Marta Peixoto Mario Valdés Ricardo da Silveira Lobo Sternberg volume 79 DON QUIXOTE AND CATHOLICISM Rereading Cervantine Spirituality Michael J. McGrath Purdue University Press West Lafayette, Indiana Copyright ©2020 by Purdue University. -

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA the Spiritual Formation

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA The Spiritual Formation of the Catholic Teacher A TREATISE Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Ministry © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Domenico Pullano Washington, D.C. 2017 The Spiritual Formation of the Catholic Teacher Dominic Pullano, D. Min. Director: Rev. Raymond Studzinski, OSB, Ph.D. Although the faith formation of Catholic teachers is recognized as an essential aspect of their training by both church documents and Catholic school boards, their spiritual formation is often overlooked. In order to be effective in transmitting the faith to their students, Catholic teachers also require on-going, life-long spiritual formation. Since there are no spiritual formation programs in the Catholic school boards of Ontario in which he works, the researcher attempts to design a spiritual formation program for Catholic teachers. Based on a survey of both contemporary and Catholic spirituality, the researcher maintains that a spiritual formation program begins with the concrete issues faced by the participants and then matches them with practices from the Catholic spiritual tradition. The researcher examined the challenges that characterize the lives of Catholic teachers, such as work/life balance, stress, low morale, and decision-making and determined that modern understandings of Sabbath keeping and Ignatian spirituality, among others, would especially benefit Catholic teachers. The researcher then took twenty-five Catholic teachers through the spiritual formation program that he designed. The program consisted of eight sessions. In four of the sessions, the researcher presented various aspects of the Catholic spiritual tradition and provided the participants with spiritual practices to employ between sessions. -

Review Jerome W. Berryman, Children and the Theologians

Review Jerome W. Berryman, Children and the Theologians: Clearing the Way for Grace (New York: Morehouse, 2009). 276 pages. $35. Reviewer: John Wall [email protected] Though the theological study of children has come a long way in recent years, it still occupies a sequestered realm within larger theological inquiry. While no church leader or theologian today can fail to consider issues of gender, race, ethnicity, or culture, the same cannot be said for age. Jerome Berryman’s Children and the Theologians: Clearing the Way for Grace Journal of Childhood and Religion Volume 1 (2010) ©Sopher Press (contact [email protected]) Page 1 of 5 takes a major step toward including children in how the very basics of theology are done. This step is to show that both real children and ideas of childhood have consistently influenced thought and practice in one way or another throughout Christian history, and that they can and should do so in creative ways again today. Berryman, the famed inventor of the children’s spiritual practice of godly play, now extends his wisdom and experience concerning children into a deeply contemplative argument that children are sacramental “means of grace.” The great majority of Children and the Theologians is a patient guide through the lives and writings of at least twenty-five important historical theologians. The reader is led chapter by chapter through the gospels, early theology, Latin theology, the Reformation, early modernity, late modernity, and today. Each chapter opens with the discussion of a work or works of art. Theologians include those with better known ideas on children such as Jesus, Paul, Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, John Calvin, Friedrich Schleiermacher, and Karl Rahner; and some less often thought about in relation to children such as Irenaeus, Anselm, Richard Hooker, Blaise Pascal, and Rowan Williams. -

Revisiting the Franciscan Doctrine of Christ

Theological Studies 64 (2003) REVISITING THE FRANCISCAN DOCTRINE OF CHRIST ILIA DELIO, O.S.F. [Franciscan theologians posit an integral relation between Incarna- tion and Creation whereby the Incarnation is grounded in the Trin- ity of love. The primacy of Christ as the fundamental reason for the Incarnation underscores a theocentric understanding of Incarnation that widens the meaning of salvation and places it in a cosmic con- tent. The author explores the primacy of Christ both in its historical context and with a contemporary view toward ecology, world reli- gions, and extraterrestrial life, emphasizing the fullness of the mys- tery of Christ.] ARL RAHNER, in his remarkable essay “Christology within an Evolu- K tionary View of the World,” noted that the Scotistic doctrine of Christ has never been objected to by the Church’s magisterium,1 although one might add, it has never been embraced by the Church either. Accord- ing to this doctrine, the basic motive for the Incarnation was, in Rahner’s words, “not the blotting-out of sin but was already the goal of divine freedom even apart from any divine fore-knowledge of freely incurred guilt.”2 Although the doctrine came to full fruition in the writings of the late 13th-century philosopher/theologian John Duns Scotus, the origins of the doctrine in the West can be traced back at least to the 12th century and to the writings of Rupert of Deutz. THE PRIMACY OF CHRIST TRADITION The reason for the Incarnation occupied the minds of medieval thinkers, especially with the rise of Anselm of Canterbury and his satisfaction theory. -

Rediscover Catholicism – Week 19 Part Three, the Seven Pillars Of

Rediscover Catholicism – Week 19 Part Three, The Seven Pillars of Catholic Spirituality Chapter 18: The Rosary Jim Castle was tired when he boarded his flight one night in Cincinnati. The forty-five-year-old management consultant had put on a weeklong series of business meetings and seminars, and now he sank gratefully into his seat, ready for the flight home to Kansas City. As more passengers boarded, the plane hummed with conversation, mixed with the sound of bags being stowed. Then, suddenly, people fell silent. The quiet moved slowly up the aisle like an invisible wake behind a boat. Jim craned his neck to see what was happening and his mouth dropped open. Walking up the aisle were two nuns clad in simple white habits with blue borders. He immediately recognized the familiar face, wrinkled skin, and warm eyes of one of the nuns. This was the face he’d seen so often on television and on the cover of Time. The two nuns halted, and Jim realized that his seat companion was going to be Mother Teresa. As the last few passengers settled in, Mother Teresa and her companion pulled out rosaries. Jim noticed that each decade of the beads was a different color. The decades represented various areas of the world, Mother Teresa told him later, adding, “I pray for the poor and dying on each continent.” The airplane taxied to the runway, and the two women began to pray, their voices in a low murmur. Though Jim considered himself a not very engaged Catholic who went to church mostly out of habit, inexplicably he found himself joining in. -

Rahner's Christian Pessimism: a Response to the Sorrow of Aids Paul G

Theological Studies 58(1997) RAHNER'S CHRISTIAN PESSIMISM: A RESPONSE TO THE SORROW OF AIDS PAUL G. CROWLEY, S.J. [Editor's Note: The author suggests that the universal sorrow of AIDS stands as a metaphor for other forms of suffering and raises distinctive theological questions on the meaning of hope, God's involvement in evil, and how God's empathy can be ex perienced in the mystery of disease. As an expression of radical realism and hope, Rahner's theology helps us find in the sorrow of AIDS an opening into the mystery of God.] N ONE OF his novels, Nikos Kazantzakis describes St. Francis of As I sisi asking in prayer what more God might require of him. Francis has already restored San Damiano and given up everything else for God. Yet he is riddled with fear of contact with lepers. He confides to Brother Leo: "Even when Fm far away from them, just hearing the bells they wear to warn passers-by to keep their distance is enough to make me faint"1 God's response to Francis's prayer is precisely what he does not want: Francis is to face his fears and embrace the next leper he sees on the road. Soon he hears the dreaded clank of the leper's bell. Yet Francis moves through his fears, embraces the leper, and even kisses his wounds. Jerome Miller, in his phenomenology of suffering, describes the importance of this scene: Only when he embraced that leper, only when he kissed the very ulcers and stumps he had always found abhorrent, did he experience for the first time that joy which does not come from this world and which he would later identify with the joy of crucifixion itself... -

Ventures in Existential Theology: the Wesleyan Quadrilateral And

VENTURES IN EXISTENTIAL THEOLOGY: THE WESLEYAN QUADRILATERAL AND THE HEIDEGGERIAN LENSES OF JOHN MACQUARRIE, RUDOLF BULTMANN, PAUL TILLICH, AND KARL RAHNER by Hubert Woodson, III Bachelor of Arts in English, 2011 University of Texas at Arlington Arlington, TX Master of Education in Curriculum and Instruction, 2013 University of Texas at Arlington Arlington, TX Master of Theological Studies, 2013 Brite Divinity School, Texas Christian University Fort Worth, TX Master of Arts in English, 2014 University of North Texas Denton, TX Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Brite Divinity School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Theology in History and Theology Fort Worth, TX May 2015 VENTURES IN EXISTENTIAL THEOLOGY: THE WESLEYAN QUADRILATERAL AND THE HEIDEGGERIAN LENSES OF JOHN MACQUARRIE, RUDOLF BULTMANN, PAUL TILLICH, AND KARL RAHNER APPROVED BY THESIS COMMITTEE: Dr. James O. Duke Thesis Director Dr. David J. Gouwens Reader Dr. Jeffrey Williams Associate Dean for Academic Affairs Dr. Joretta Marshall Dean WARNING CONCERNING COPYRIGHT RESTRICTIONS The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish photocopy or reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law.