Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

Checklist of Fish and Invertebrates Listed in the CITES Appendices

JOINTS NATURE \=^ CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Checklist of fish and mvertebrates Usted in the CITES appendices JNCC REPORT (SSN0963-«OStl JOINT NATURE CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Report distribution Report Number: No. 238 Contract Number/JNCC project number: F7 1-12-332 Date received: 9 June 1995 Report tide: Checklist of fish and invertebrates listed in the CITES appendices Contract tide: Revised Checklists of CITES species database Contractor: World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 ODL Comments: A further fish and invertebrate edition in the Checklist series begun by NCC in 1979, revised and brought up to date with current CITES listings Restrictions: Distribution: JNCC report collection 2 copies Nature Conservancy Council for England, HQ, Library 1 copy Scottish Natural Heritage, HQ, Library 1 copy Countryside Council for Wales, HQ, Library 1 copy A T Smail, Copyright Libraries Agent, 100 Euston Road, London, NWl 2HQ 5 copies British Library, Legal Deposit Office, Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ 1 copy Chadwick-Healey Ltd, Cambridge Place, Cambridge, CB2 INR 1 copy BIOSIS UK, Garforth House, 54 Michlegate, York, YOl ILF 1 copy CITES Management and Scientific Authorities of EC Member States total 30 copies CITES Authorities, UK Dependencies total 13 copies CITES Secretariat 5 copies CITES Animals Committee chairman 1 copy European Commission DG Xl/D/2 1 copy World Conservation Monitoring Centre 20 copies TRAFFIC International 5 copies Animal Quarantine Station, Heathrow 1 copy Department of the Environment (GWD) 5 copies Foreign & Commonwealth Office (ESED) 1 copy HM Customs & Excise 3 copies M Bradley Taylor (ACPO) 1 copy ^\(\\ Joint Nature Conservation Committee Report No. -

224 Mavis C. Campbell Assad Shoman

224 book reviews Mavis C. Campbell Becoming Belize: A History of an Outpost of Empire Searching for Identity, 1528–1823. Kingston: University of the West Indies Press, 2011. xxii + 425 pp. (Paper US$50.00) Assad Shoman A History of Belize in Thirteen Chapters. 2nd edition. Belize City: The Angelus Press, 2011. xvii + 461 pp. (Paper US$30.00) Modern Belize is commonly referred to as a Caribbean nation in Central Amer- ica. Geographically part of Central America, its English language use and polit- ical history make it part of the Anglophone Caribbean, which may explain in part its relative neglect by scholars of both regions. While Mavis Campbell is not correct to state that Narda Dodson’s A History of Belize (1973) is “the only comprehensive history of Belize written by a trained historian” (p. xiv), she is certainly right to assert that Belizean history “deserves more attention” (p. 4). The enlarged edition of Assad Shoman’s 1994 history is a new contribution aimed at filling the gap. Becoming Belize adds significantly to our understanding of Belize’s begin- nings. Although Campbell did not investigate Spanish primary sources in Ma- drid and Seville, she consulted archives in Belize and Jamaica, at British insti- tutions, and, briefly, in Mérida. The book’s first section examines Spanish at- tempts at settling Belize, from about 1528 to 1708. Campbell explores why Belize became British, given the region’s history, and revisits early Spanish exploration, including Columbus’s 1502 voyage to the Bay Islands of modernity, when he came closest to Belize, and the 1511 shipwreck that left two Spaniards, Gerónimo de Aguilar and Gonzalo Guerrero, in the Yucatán. -

Download the Meeting Program, Including Abstracts

PROGRAM: Overview of oral and poster presentations FINAL PROGRAM 37th AMLC SCIENTIFIC MEETING CURACAO (MAY 18-22, 2015) MAY 17 17:00 Registration (optional) and "ice breaker" on the beach at Carmabi END of DAY 0 (MAY 17) MAY 18 8:00 Registration at the Hilton Hotel 9:00 Official opening 37th AMLC Meeting The Eastern Caribbean: A laboratory for studying the resilience and 9:30 PLENARY: DR. B. STENECK management of coral reefs 10:30 Coffee break Time Authors Title Shifting baselines: three decades of nitrogen enrichment on two 11:00 * Lapointe B, Herren L, Tarnowski, M, Dustan P Caribbean coral reefs Finding a new path towards reef conservation: Antigua’s community- 11:15 S Camacho R, Steneck R based no-take reserves Lyons P, Arboleda E, Benkwitt C, Davis B, Gleason M, Howe 11:30 * C, Mathe J, Middleton J, Sikowitz N, Untersteggaber L, The effect of recreational scuba diving on the benthic community Villalobos S assemblage and structural complexity of Caribbean coral reefs Perspective on how fast and efficient sponge engines drive and 11:45 * De Goeij JM modulate the food web of reef ecosystems Lesion recovery of two scleractinian corals under low pH: 12:00 S Dungan A, Hall ER, DeGroot BC, Fine M implications for restoration efforts Session chair: Kristen Marhaver Kristen chair: Session The status of coral reefs and marine fisheries in Jamaica’s Portland 12:15 * Palmer SE, Lang JC Bight Protected Area to inform proposed development decisions 12:30 Lunch (can be obtained at the Hilton, Carmabi (next to Hilton) or nearby restaurants and bars Historical analysis of ciguatera incidence in the Caribbean islands 13:30 * Mancera-Pineda JE, Celis JS, Gavio B during 31 years: 1980-2010 Smith TB, Richlen ML, Robertson A, Liefer JD, Anderson DM, Ciguatera fish poisoning: long-term dynamics of Gambierdiscus spp. -

Stories Matter: the Complexity of Cultural Authenticity in Children's Literature (Pp

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 480 339 CS 512 399 AUTHOR Fox, Dana L., Ed.; Short, Kathy G., Ed. TITLE Stories Matter: The Complexity of CulturalAuthenticity in Children's Literature. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana,IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-4744-5 PUB DATE 2003-00-00 NOTE 345p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers ofEnglish, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana,.IL 61801-1096 (Stock no. 47445: $26.95members; $35.95 nonmembers). Tel: 800-369-6283 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.ncte.org. PUB TYPE Books (010).-- Collected Works General (020) -- Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Childrens Literature; *Cultural Context; ElementaryEducation; *Literary Criticism; *Multicultural Literature;Picture Books; Political Correctness; Story Telling IDENTIFIERS Trade Books ABSTRACT The controversial issue of cultural authenticity inchildren's literature resurfaces continually, always elicitingstrong emotions and a wide range of perspectives. This collection explores thecomplexity of this issue by highlighting important historical events, current debates, andnew questions and critiques. Articles in the collection are grouped under fivedifferent parts. Under Part I, The Sociopolitical Contexts of Cultural Authenticity, are the following articles: (1) "The Complexity of Cultural Authenticity in Children's Literature:Why the Debates Really Matter" (Kathy G. Short and Dana L. Fox); and (2)"Reframing the Debate about Cultural Authenticity" (Rudine Sims Bishop). Under Part II,The Perspectives of Authors, -

Afro-Descendants, Discrimination and Economic Exclusion in Latin America by Margarita Sanchez and Maurice Bryan, with MRG Partners

macro study Afro-descendants, Discrimination and Economic Exclusion in Latin America By Margarita Sanchez and Maurice Bryan, with MRG partners Executive summary Also, Afro-descendants do not have a significant voice in the This macro study addresses the economic exclusion of people planning, design or implementation of the policies and activi- of African descent (Afro-descendants) in Latin America. It ties that directly affect their lives and regions. This is an aims to examine how and why race and ethnicity contribute to important omission; while Afro-descendant populations may the disproportionately high levels of poverty and economic dis- be materially poor, they have a rich cultural heritage and access crimination in most Afro-descendant communities, and how to key natural resources. Development strategies need to recog- to promote change. nize the historical, social and cultural complexity of There are clear links between Afro-descendant communi- Afro-descendants’ poverty and consult them on the most cul- ties and poverty, however there is a need for disaggregated data turally appropriate means of achieving positive change. to provide a more precise picture, and to enable better plan- The views of Afro-descendants are central to much of the ning and financing of development programmes for this highly information used in this study, which uses a rights-based marginalized group. approach. The study explains some of the causes and conse- A prime cause for the lack of quantitative material, is that quences of Afro-descendants’ exclusion, and offers donors and governments have only recently begun to acknowl- recommendations for a more inclusive minority rights-based edge Afro-descendant populations’ existence. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Erich Poncza The Impact of American Minstrelsy on Blackface in Europe Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. 2017 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature 1 I would like to thank my supervisor Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. for his guidance and help in the process of writing my bachelor´s theses. 2 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………..………....……5 1. Stereotyping………………………………………..…….………………..………….6 2. Origins of Blackface………………………………………………….…….……….10 3. Blackface Caricatures……………………………………………………………….13 Sambo………………………………………………………….………………14 Coon…………………………………………………………………….……..15 Pickaninny……………………………………………………………………..17 Jezebel…………………………………………………………………………18 Savage…………………………………………………………………………22 Brute……………………………………………………….………........……22 4. European Blackface and Stereotypes…………………………..……….….……....26 Minstrelsy in England…………………………………………………………28 Imagery………………………………………………………………………..31 Blackface………………………………………………………..…………….36 Czech Blackface……………………………………………………………….40 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………….44 Images…………………………………………………………………………………46 Works Cited………………………………………………………………….………..52 Summary………………………………………………………….……………………59 Resumé……………………………………………………………………..………….60 3 Introduction Blackface is a practice that involves people, mostly white, painting their faces -

Orisha Journeys: the Role of Travel in the Birth of Yorùbá-Atlantic Religions 1

Arch. de Sc. soc. des Rel., 2002, 117 (janvier-mars) 17-36 Peter F. COHEN ORISHA JOURNEYS: THE ROLE OF TRAVEL IN THE BIRTH OF YORÙBÁ-ATLANTIC RELIGIONS 1 Introduction 2 In recent years the array of Orisha 3 traditions associated withtheYorùbá- speaking peoples of West Africa has largely broken free of the category of “Afri- can traditional religion” and begun to gain recognition as a nascent world religion in its own right. While Orisha religions are today both trans-national and pan-eth- nic, they are nonetheless the historical precipitate of the actions and interactions of particular individuals. At their human epicenter are the hundreds of thousands of Yorùbá-speaking people who left their country during the first half of the 19th cen- tury in one of the most brutal processes of insertion into the world economy under- gone by any people anywhere; the Atlantic slave trade. While the journey of the Middle Passage is well known, other journeys under- taken freely by Africans during the period of the slave trade – in a variety of direc- tions, for a multiplicity of reasons, often at great expense, and sometimes at great personal risk – are less so. These voyages culminated in a veritable transmigration involving thousands of Yorùbá-speaking people and several points on both sides of 1 Paper presented at the 1999 meeting of the Société Internationale de la Sociologie des Religions. This article was originally prepared in 1999. Since then, an impressive amount of literature has been published on the subject, which only serves to strengthen our case. A great deal of new of theoretical work on the African Diaspora in terms of trans-national networks and mutual exchanges has not so much challenged our arguments as diminished their novelty. -

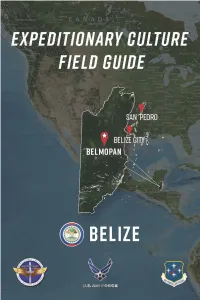

ECFG-Belize-2020R.Pdf

ECFG: Central America Central ECFG: About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: US Marine shows members of Belize Defense Force how to load ammunition into weapons). The guide consists of 2 E parts: CFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on Central America (CENTAM). Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Belize Belizean society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre- deployment training (Photo: USAF medic checks a Belizean patient’s vision during a medical readiness event). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

Lorain Puerto Rican Spanish and 'R' in Three Generations

Lorain Puerto Rican Spanish and ‘r’ in Three Generations Michelle F. Ramos-Pellicia George Mason University 1. Problem Retroflex ‘r’ in coda position, has been documented in the Spanish of the Yucatan Peninsula, central areas of Costa Rica, Belize, other parts of Central America, as well as in the US Southwest (Alonso 1930; Cassano 1973, 1977; Figueroa and Hislope 1998; Hagerty 1996; Lastra de Suárez 1975; Lipski 1994; Orenstein 1974; Sánchez 1972). In these dialects, the retroflex pronunciation generally has been assumed to result from American English (AE) influence, but the cause has not been directly studied. The analysis of retroflex /r/ in Puerto Rican Spanish in Lorain, Ohio --where contact with English is ongoing and variable-- presents counterevidence to the hypothesized AE source of retroflex /r/. In this article, I discuss the frequency patterns of use for ‘r’ among three generations of Puerto Ricans in Lorain, Ohio. The retroflex ‘r’ is most common in the third generation, a fact which is consistent with AE influence. However, if AE were the source, we would expect the lowest frequency of the retroflex in the first generation Puerto Ricans, as they are presumed to have the least contact with English. In fact, however, first generation speakers use a retroflex ‘r’ in their readings in Spanish more frequently than the second generation. The AE influence explanation is, then, problematic, and despite the evidence from the second and third generations, the occurrence of ‘r’ in the first generation cannot be attributed solely to AE influence. In addition to offering possible explanations of the data, I discuss methodological issues in the operationalization and measurement of 'language contact'. -

Mixed Verbs in Contact Spanish: Patterns of Use Among Emergent and Dynamic Bi/Multilinguals

languages Article Mixed Verbs in Contact Spanish: Patterns of Use among Emergent and Dynamic Bi/Multilinguals Osmer Balam Department of Spanish and Portuguese Studies, University of Florida, 170 Dauer Hall, Gainesville, FL 32611-7405, USA; obalam@ufl.edu; Tel.: +1-352-392-9222 Academic Editors: Usha Lakshmanan and Tej K. Bhatia Received: 18 October 2015; Accepted: 7 March 2016; Published: 23 March 2016 Abstract: The present study provides a quantitative analysis of mixed verbs in the naturalistic speech of 20 Northern Belize bi/multilinguals of two different age groups (ages 14–20 and ages 21–40). I examined the relative frequency of Spanish/English mixed verbs vis-à-vis syntactic verb type and phrasal verbs in mixed verbs. Results showed that the token frequency of mixed verbs was a predictive measure of the relative frequency of ‘hacer + V’ in code-switched speech. In relation to syntactic verb type, it was found that the least productivity in terms of argument structures was attested among the youngest group of emergent bi/multilinguals. For the incorporation of phrasal verbs in mixed verbs, no marked differences were attested in the relative frequency of phrasal verbs across emergent and dynamic bi/multilinguals, but differences did emerge in the semantic nature of phrasal verbs. Findings highlight the fundamental role that adult code-switchers with higher levels of bi/multilingual proficiency play in the creation and propagation of morphosyntactic innovations. Keywords: Northern Belizean Spanish; mixed verbs; bilingual compound verbs; light verb constructions; Spanish/English code-switching; linguistic innovation 1. Introduction In the Spanish-speaking world, mixed verbs1 or bilingual compound verbs have been documented in several bi/multilingual contexts involving Creole [1]; Germanic (English: [1–5]; German: [6]); Mayan (Chontal Maya: [7]; Yucatec Maya: [8]); Oto-Manguean (Popoloca: [9], cited in Muysken [10] (p. -

Multiculturalism, Afro-Descendant Activism, and Ethnoracial Law and Policy in Latin America

Rahier, Jean Muteba. 2020. Multiculturalism, Afro-Descendant Activism, and Ethnoracial Law and Policy in Latin America. Latin American Research Review 55(3), pp. 605–612. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.1094 BOOK REVIEW ESSAYS Multiculturalism, Afro-Descendant Activism, and Ethnoracial Law and Policy in Latin America Jean Muteba Rahier Florida International University, US [email protected] This essay reviews the following works: Seams of Empire: Race and Radicalism in Puerto Rico and the United States. By Carlos Alamo-Pastrana. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2016. Pp. xvi + 213. $79.95 hardcover. ISBN: 9780813062563. Civil Rights and Beyond: African American and Latino/a Activism in the Twentieth-Century United States. Edited by Brian D. Behnken. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2016. Pp. 270. $27.95 paperback. ISBN: 9780820349176. Afro-Politics and Civil Society in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil. By Kwame Dixon. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2016. Pp. xiii + 174. $74.95 hardcover. ISBN: 9780813062617. Black Autonomy: Race, Gender, and Afro-Nicaraguan Activism. By Jennifer Goett. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2017. Pp. ix + 222. $26.00 paperback. ISBN: 9781503600546. The Politics of Blackness: Racial Identity and Political Behavior in Contemporary Brazil. By Gladys L. Mitchell-Walthour. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018. Pp. xvi + 266. $34.99 paperback. ISBN: 9781316637043. The Geographies of Social Movements: Afro-Colombian Mobilization and the Aquatic Space. By Ulrich Oslender. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016. Pp. xiii + 290. $25.95 paperback. ISBN: 9780822361220. Becoming Black Political Subjects: Movements and Ethno-Racial Rights in Colombia and Brazil. By Tianna S. Paschel. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.