Candle in the Dark: COMINT and Soviet Industrial Secrets,1946-1956

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computers and Economic Democracy

Rev.econ.inst. vol.1 no.se Bogotá 2008 COMPUTERS AND ECONOMIC DEMOCRACY Computadores y democracia económica Allin Cottrell; Paul Cockshott Ph.D. in Economics, professor of Wake Forest University, Winston Salem, USA, [[email protected]]. Ph.D. in Computer Science, researcher of the Glasgow University, Glasgow, United Kingdom, [[email protected]].. The collapse of previously existing socialism was due to causes embedded in its economic mechanism, which are not inherent in all possible socialisms. The article argues that Marxist economic theory, in conjunction with information technology, provides the basis on which a viable socialist economic program can be advanced, and that the development of computer technology and the Internet makes economic planning possible. In addition, it argues that the socialist movement has never developed a correct constitutional program, and that modern technology opens up opportunities for democracy. Finally, it reviews the Austrian arguments against the possibility of socialist calculation in the light of modern computational capacity and the constraints of the Kyoto Protocol. [Keywords: socialist planning, economic calculation, environmental constraints; JEL: P21, P27, P28] El colapso del socialismo anteriormente existente obedeció a causas integradas en su mecanismo económico, que no son inherentes a todos los socialismos posibles. El artículo muestra que la teoría económica marxista, junto con la informática, proporciona el fundamento para adelantar un programa económico socialista viable y que el desarrollo de la informática y de Internet hace posible la planificación económica. Además, argumenta que el movimiento socialista nunca desarrolló un programa constitucional correcto y que la tecnología moderna abre nuevas oportunidades para la democracia. -

Inside Russia's Intelligence Agencies

EUROPEAN COUNCIL ON FOREIGN BRIEF POLICY RELATIONS ecfr.eu PUTIN’S HYDRA: INSIDE RUSSIA’S INTELLIGENCE SERVICES Mark Galeotti For his birthday in 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin was treated to an exhibition of faux Greek friezes showing SUMMARY him in the guise of Hercules. In one, he was slaying the • Russia’s intelligence agencies are engaged in an “hydra of sanctions”.1 active and aggressive campaign in support of the Kremlin’s wider geopolitical agenda. The image of the hydra – a voracious and vicious multi- headed beast, guided by a single mind, and which grows • As well as espionage, Moscow’s “special services” new heads as soon as one is lopped off – crops up frequently conduct active measures aimed at subverting in discussions of Russia’s intelligence and security services. and destabilising European governments, Murdered dissident Alexander Litvinenko and his co-author operations in support of Russian economic Yuri Felshtinsky wrote of the way “the old KGB, like some interests, and attacks on political enemies. multi-headed hydra, split into four new structures” after 1991.2 More recently, a British counterintelligence officer • Moscow has developed an array of overlapping described Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) as and competitive security and spy services. The a hydra because of the way that, for every plot foiled or aim is to encourage risk-taking and multiple operative expelled, more quickly appear. sources, but it also leads to turf wars and a tendency to play to Kremlin prejudices. The West finds itself in a new “hot peace” in which many consider Russia not just as an irritant or challenge, but • While much useful intelligence is collected, as an outright threat. -

Number 32 the Second Currency in the Soviet Union: on the Use of Checks in "Valuta-Rubles" by Soviet Citizens

NUMBER 32 THE SECOND CURRENCY IN THE SOVIET UNION: ON THE USE OF CHECKS IN "VALUTA-RUBLES" BY SOVIET CITIZENS by Dietrich Andre Loeber Fellow, Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies COLLOQUIUM April 18, 1978 ,. Preliminary draft. Not to be quoted or cited without the author's permission. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page # I. The Question Posed 1 II. How the Second Currency System Works 2 1. Rubles and Valuta-Rubles 2 2. Valuta-Checks 2 3. Administration of the Valuta-Check System 3 4. Persons Entitled to Use the Valuta-Check System 4 5. Where do Valuta-Checks Circulate 6 6. What Can be Bought for Valuta-Checks 7 7. And at What Prices 8 8. How Long a Second Currency Has Been Used 8 III. Enjoying the Advantages: The Economic Side 10 IV. Facing up to Reality in the Statutes: Legal Aspects 11 V. Uneasy Compromise: Ideological Implications 12 VI. Control of the Consequences: The Socio-Political Dimension 14 Appendix 1-3 Terms Used Explained on Page Val uta-Check 3 Valuta-Ruble 2 Val uta-Store 3 © D.~A~ Loeber 1978 THE SECOND CURRENCY IN THE SOVIET UNION: ON THE USE OF CHECKS IN "VALUTA-RUBLES" BY SOVIET CITIZENS by Dietrich Andre Loeber Fellow, Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies I. THE QUESTION POSED The title of this paper may seem provocative. We are used to thinking that there is just one currency in the Soviet Union - the ruble. I thought so myself until I spent my sabbatical in ~1oscow last year. There I saw that a second currency in fact circulates in the USSR. -

Revolution in Real Time: the Russian Provisional Government, 1917

ODUMUNC 2020 Crisis Brief Revolution in Real Time: The Russian Provisional Government, 1917 ODU Model United Nations Society Introduction seventy-four years later. The legacy of the Russian Revolution continues to be keenly felt The Russian Revolution began on 8 March 1917 to this day. with a series of public protests in Petrograd, then the Winter Capital of Russia. These protests But could it have gone differently? Historians lasted for eight days and eventually resulted in emphasize the contingency of events. Although the collapse of the Russian monarchy, the rule of history often seems inventible afterwards, it Tsar Nicholas II. The number of killed and always was anything but certain. Changes in injured in clashes with the police and policy choices, in the outcome of events, government troops in the initial uprising in different players and different accidents, lead to Petrograd is estimated around 1,300 people. surprising outcomes. Something like the Russian Revolution was extremely likely in 1917—the The collapse of the Romanov dynasty ushered a Romanov Dynasty was unable to cope with the tumultuous and violent series of events, enormous stresses facing the country—but the culminating in the Bolshevik Party’s seizure of revolution itself could have ended very control in November 1917 and creation of the differently. Soviet Union. The revolution saw some of the most dramatic and dangerous political events the Major questions surround the Provisional world has ever known. It would affect much Government that struggled to manage the chaos more than Russia and the ethnic republics Russia after the Tsar’s abdication. -

From Archives of Vuchk-GPU-NKVD-KGB Chernobyl Tragedy in Documents and Materials (Summary)

From Archives of VUChK-GPU-NKVD-KGB Chernobyl Tragedy in Documents and Materials (Summary) Volodymyr Tykhyy General overview of the book The book "From archives of VUChK-GPU-NKVD-KGB. Chernobyl tragedy in documents and materials" (Z arhiviv VUCHK-GPU-NKVD-KGB. Chornobylska tragedia v dokumentakh ta materialakh, №1(16) 2001) was published by the Security Service of Ukraine (SSU) in 2001. SSU is a natural continuation of the Soviet KGB (Committee of the State Security of the USSR), so SSU inherited KGB archives and disclosed some documents when the appropriate legislation was passed by the Parliament of Ukraine beginning in 1994 with the Law "On State Secrets". It is essential to note that on 10 December 2005 the book was also posted on the web-site of the SSU (http://www.sbu.gov.ua/sbu/control/uk/publish/article?art_id=39296&cat_id=46616). KGB is a unique source of information, because it worked "across the lines": it was subordinated neither to nuclear industry nor to army generals; it supervised activities of industry, government and municipal authorities, construction companies and cooperative shops alike. KGB officers collected information from all sources they deemed reliable, they often were able to cross-check it and then to present to higher levels of hierarchy - in KGB, Communist Party, Government of Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. So, this information contained quite reliable facts, which were formulated without flatter - moreover, it was either "secret" or "top secret". Unfortunately, this does not mean that their reports were given any special attention - the system had its own inertia, and KGB was an integral part of the system. -

Bul NKVD AJ.Indd

The NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Central and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 Anthology of the international conference Bratislava 14. – 16. 11. 2007 Edited by Alexandra Grúňová Nation´s Memory Institute BRATISLAVA 2008 Anthology was published with kind support of The International Visegrad Fund. Visegrad Fund NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Cen- tral and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 14 – 16 November, 2007, Bratislava, Slovakia Anthology of the international conference Edited by Alexandra Grúňová Published by Nation´s Memory Institute Nám. SNP 28 810 00 Bratislava Slovakia www.upn.gov.sk 1st edition English language correction Anitra N. Van Prooyen Slovak/Czech language correction Alexandra Grúňová, Katarína Szabová Translation Jana Krajňáková et al. Cover design Peter Rendek Lay-out, typeseting, printing by Vydavateľstvo Michala Vaška © Nation´s Memory Institute 2008 ISBN 978-80-89335-01-5 Nation´s Memory Institute 5 Contents DECLARATION on a conference NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Central and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 ..................................................................9 Conference opening František Mikloško ......................................................................................13 Jiří Liška ....................................................................................................... 15 Ivan A. Petranský ........................................................................................ -

Ill[S ADJUSTMENTS

B249 DATA TRANSMISSION CONTROL UNIT INTRODUCTION AND OPERATION Burroughs FUNCTIONAL DETAIL FIELD ENGINEERING CIRCUIT DETAIL lJrn~[}{] ~ D~ill[s ADJUSTMENTS MAINTENANCE ~ ill ~ OD ill [S PROCEDURES INST ALLAT ION PROCEDURES RELIABILITY IMPROVEMENT NOTICES OPTIONAL FEATURES MODIFICATIONS (BRANCH LIBRARIES) Printed in U.S. America 9-15-66 Form 1026259 Burroughs - B249 Data Transmission ~echnical Manual I N D E X INTRODUCTION & OPERATION - SECTION I Page No. B249 Data Transmission Control Unit - General Descript ion . 1 Glossary - Data Transmission Terminal Unit and MCU. 5 Glossary - DTCU & System . 3 Physical De$cr1ption . 2 FUNCTIONAL DETAIL - SECTION II B300 Active Interrogate. · . · . · · 57 B300 Data Communications Read. · · . · · · · 62 B300 Data Communications Write · · . 78 B300 Passive Interrogate · · 49 VB300 Passive Interrogate - ITU (B486) Mode · . 92 v13300 Read - ITU (B486) Mode. · · . · · . · . 95 V'B300 Write - ITU (13486) Mode · · . · · 108 B5500 Data Communications Interrogate. · . 1 B5500 Data Communications Read . · 9 B5500 Data Communications Write. · 21 CIRCUIT DETAIL - SECTION III "AU Register Load - (Normal & Reverse) 1 Clock Control. ... 11 Scan . 3 Translator . 4 ADJUSTMENTS - SECTION IV Clock Adjustments ..... 1 Variable Bias Adjustment . 1 MAINTENANCE PROCEDURES - SECTION V Maintenance Panel ... 1 INSTALLATION PROCEDURES - SECTION VI DTCU Installation. 1 Pluggable Options. 2 Power ON . 3 Special Inquiry Terminal Connection .. 2 NOTE: Pages for Sections VII, VIII and IX will be furnished when applicable. Printed in U. S. America Revised 4/1/67 For Form 1026259 Burroughs - B249 Data Transmission Technical Manual Sec, I Page 1 Introduction & Operation B249 DATA TRANSMISSION CONTROL UNIT - GENERAL DESCRIPTION The B249 DTCU is required when: 1. More than one B487 DTTU is used on a single Processing System. -

Relink Eo 3-11-97

CHAPTER 1 COMMUNICATIONS As an Aviation Electronics Technician, you will be communication circuits. These operations are accom- tasked to operate and maintain many different types of plished through the use of compatible and flexible airborne communications equipment. These systems communication systems. may differ in some respects, but they are similar in many Radio is the most important means of com- ways. As an example, there are various models of AM municating in the Navy today. There are many methods radios, yet they all serve the same function and operate of transmitting in use throughout the world. This manual on the same basic principles. It is beyond the scope of will discuss three types. They are radiotelegraph, this manual to discuss each and every model of radiotelephone, and teletypewriter. communication equipment used on naval aircraft; therefore, only representative systems will be discussed. Every effort has been made to use not only systems that Radiotelegraph are common to many of the different platforms, but also have not been used in the other training manuals. It is Radiotelegraph is commonly called CW (con- the intent of this manual to have systems from each and tinuous wave) telegraphy. Telegraphy is accomplished every type of aircraft in use today. by opening and closing a switch to separate a continuously transmitted wave. The resulting “dots” and “dashes” are based on the Morse code. The major RADIO COMMUNICATIONS disadvantage of this type of communication is the relatively slow speed and the need for experienced Learning Objective: Recognize the various operators at both ends. types of radio communications. -

Divided Strategies and Political Crisis in a Soviet Enterprise

SOVIET STUDIES, Vol. 44, NO. 3, 1992, 37 1-402 Between Perestroika and Privatisation: Divided Strategies and Political Crisis in a Soviet Enterprise MICHAEL BURAWOY & KATHRYN HENDLEY INTHE CLASSIC STUDIES of the Soviet enterprise, the failures of central planning are attributed not to some traditional or 'non-economic' logic but to the enterprise's rational pursuit of its own interests.' Thus, enterprises bargain for loose plan targets by hiding resources, by not overfulfilling plans and by exaggerated underfulfilment of difficult targets. Enterprise performance is evaluated according to plan indicators which, if followed, lead to wasteful use of resources and the production of goods no one wants-heavy machinery, thin glass or large nak2So, the classic studies conclude, within a planned economy it is impossible to create an incentive system that stimulates the production of what is needed. The more recent literature on enterprises in the reformed economies of Eastern Europe, particularly the Hungarian economy, argues that pathologies persist when physical planning gives way to fiscal planning. Janos Kornai argues that soft budget constraints inevitably follow from state ownership of the means of production, and therefore enterprises seek to increase their bargaining power with the state by expanding as rapidly as p~ssible.~This results in a distribution of investment resources which is unrelated to enterprise efficiency or profitability. In a more elaborate bargaining model, Tamas Bauer shows how enterprises entice government sponsorship of new investment schemes by underestimating the costs of new project^.^ Once hooked, the government can be subjected to considerable pressure to continue financing the new project even as costs escalate. -

Law Enforcement Intelligence: a Guide for State, Local, and Tribal Law Enforcement Agencies Second Edition

U. S. Department of Justice Office of Community Oriented Policing Services Law Enforcement Intelligence: A Guide for State, Local, and Tribal Law Enforcement Agencies Second Edition David L. Carter, Ph.D. School of Criminal Justice, Michigan State University Law Enforcement Intelligence: A Guide for State, Local, and Tribal Law Enforcement Agencies Second Edition David L. Carter, Ph.D. School of Criminal Justice, Michigan State University This project was supported by Cooperative Agreement #2007-CK-WX-K015 by the U.S. Department of Justice Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. Points of view or opinions contained in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice or Michigan State University. References to specific agencies, companies, products, or services should not be considered an endorsement by the author or the U.S. Department of Justice. Rather, the references are illustrations to supplement discussion of the issues. Letter from the COPS Office January 2009 Dear Colleague: This second edition of Law Enforcement Intelligence: A Guide for State, Local, and Tribal Law Enforcement captures the vast changes that have occurred in the 4 years since the first edition of the guide was published in 2004 after the watershed events of September 11, 2001. At that time, there was no Department of Homeland Security, Office of the Director of National Intelligence, Information-Sharing Environment, or Fusion Centers. Since the advent of these new agencies to help fight the war on terror, emphasis has been placed on cooperation and on sharing information among local, state, tribal, and federal agencies. -

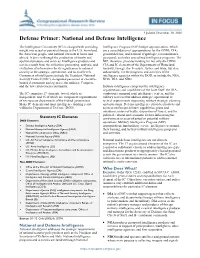

Defense Primer: National and Defense Intelligence

Updated December 30, 2020 Defense Primer: National and Defense Intelligence The Intelligence Community (IC) is charged with providing Intelligence Program (NIP) budget appropriations, which insight into actual or potential threats to the U.S. homeland, are a consolidation of appropriations for the ODNI; CIA; the American people, and national interests at home and general defense; and national cryptologic, reconnaissance, abroad. It does so through the production of timely and geospatial, and other specialized intelligence programs. The apolitical products and services. Intelligence products and NIP, therefore, provides funding for not only the ODNI, services result from the collection, processing, analysis, and CIA and IC elements of the Departments of Homeland evaluation of information for its significance to national Security, Energy, the Treasury, Justice and State, but also, security at the strategic, operational, and tactical levels. substantially, for the programs and activities of the Consumers of intelligence include the President, National intelligence agencies within the DOD, to include the NSA, Security Council (NSC), designated personnel in executive NGA, DIA, and NRO. branch departments and agencies, the military, Congress, and the law enforcement community. Defense intelligence comprises the intelligence organizations and capabilities of the Joint Staff, the DIA, The IC comprises 17 elements, two of which are combatant command joint intelligence centers, and the independent, and 15 of which are component organizations military services that address strategic, operational or of six separate departments of the federal government. tactical requirements supporting military strategy, planning, Many IC elements and most intelligence funding reside and operations. Defense intelligence provides products and within the Department of Defense (DOD). -

A Stakeholder Analysis of the Soviet Second Economy by CHOI, Jae

A Stakeholder Analysis of the Soviet Second Economy By CHOI, Jae-hyoung THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2015 A Stakeholder Analysis of the Soviet Second Economy By CHOI, Jae-hyoung THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2015 Professor Chang-Yong Choi A Stakeholder Analysis of the Soviet Second Economy By CHOI, Jae-hyoung THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY Committee in charge: Professor Chang Yong CHOI, Supervisor Professor Jung Ho YOO Professor June Soo LEE Approval as of April, 2015 Abstract This research aims to demonstrate, through a stakeholder analysis, that the institutionalization of the second economy in the Soviet Union was a natural byproduct of the interaction among three major stakeholders of Soviet society: the state, the bureaucracy, and the people. The three stakeholders responded to the incentive structure of the socialist economic system, interacting with each other in order to enhance their own interests. This research argues that their interaction was the internal necessity or dynamics that formed this informal market mechanism and elevated it to a characteristic feature of Soviet society. i Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................