Where's Mao.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case of Zhang Yiwu

ASIA 2016; 70(3): 921–941 Giorgio Strafella* Postmodernism as a Nationalist Conservatism? The Case of Zhang Yiwu DOI 10.1515/asia-2015-1014 Abstract: The adoption of postmodernist and postcolonial theories by China’s intellectuals dates back to the early 1990s and its history is intertwined with that of two contemporaneous trends in the intellectual sphere, i. e. the rise of con- servatism and an effort to re-define the function of the Humanities in the country. This article examines how these trends merge in the political stance of a key figure in that process, Peking University literary scholar Zhang Yiwu, through a critical discourse analysis of his writings from the early and mid- 1990s. Pointing at his strategic use of postmodernist discourse, it argues that Zhang Yiwu employed a legitimate critique of the concept of modernity and West-centrism to advocate a historical narrative and a definition of cultural criticism that combine Sino-centrism and depoliticisation. The article examines programmatic articles in which the scholar articulated a theory of the end of China’s “modernity”. It also takes into consideration other parallel interventions that shed light on Zhang Yiwu’s political stance towards modern China, globalisation and post-1992 economic reforms, including a discussion between Zhang Yiwu and some of his most prominent detractors. The article finally reflects on the implications of Zhang Yiwu’s writings for the field of Chinese Studies, in particular on the need to look critically and contextually at the adoption of “foreign” theoretical discourse for national political agendas. Keywords: China, intellectuals, postmodernism, Zhang Yiwu, conservatism, nationalism 1 Introduction This article looks at the early history and politics of the appropriation of post- modernist discourse in the Chinese intellectual sphere, thus addressing the plurality of postmodernity via the plurality of postmodernism. -

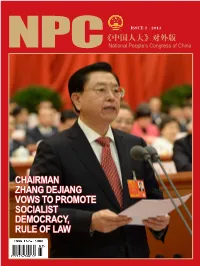

Issue 1 2013

ISSUE 1 · 2013 NPC《中国人大》对外版 CHAIRMAN ZHANG DEJIANG VOWS TO PROMOTE SOCIALIST DEMOCRACY, RULE OF LAW ISSUE 4 · 2012 1 Chairman of the NPC Standing Committee Zhang Dejiang (7th, L) has a group photo with vice-chairpersons Zhang Baowen, Arken Imirbaki, Zhang Ping, Shen Yueyue, Yan Junqi, Wang Shengjun, Li Jianguo, Chen Changzhi, Wang Chen, Ji Bingxuan, Qiangba Puncog, Wan Exiang, Chen Zhu (from left to right). Ma Zengke China’s new leadership takes 6 shape amid high expectations Contents Special Report Speech In–depth 6 18 24 China’s new leadership takes shape President Xi Jinping vows to bring China capable of sustaining economic amid high expectations benefits to people in realizing growth: Premier ‘Chinese dream’ 8 25 Chinese top legislature has younger 19 China rolls out plan to transform leaders Chairman Zhang Dejiang vows government functions to promote socialist democracy, 12 rule of law 27 China unveils new cabinet amid China’s anti-graft efforts to get function reform People institutional impetus 15 20 28 Report on the work of the Standing Chairman Zhang Dejiang: ‘Power China defense budget to grow 10.7 Committee of the National People’s should not be aloof from public percent in 2013 Congress (excerpt) supervision’ 20 Chairman Zhang Dejiang: ‘Power should not be aloof from public supervision’ Doubling income is easy, narrowing 30 regional gap is anything but 34 New age for China’s women deputies ISSUE 1 · 2013 29 37 Rural reform helps China ensure grain Style changes take center stage at security Beijing’s political season 30 Doubling -

China Perspectives, 55 | September - October 2004 the Debate Between Liberalism and Neo-Leftism at the Turn of the Century 2

China Perspectives 55 | september - october 2004 Varia The Debate Between Liberalism and Neo-Leftism at the Turn of the Century Chen Lichuan Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/417 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.417 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 October 2004 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Chen Lichuan, « The Debate Between Liberalism and Neo-Leftism at the Turn of the Century », China Perspectives [Online], 55 | september - october 2004, Online since 29 December 2008, connection on 28 October 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/417 ; DOI : 10.4000/ chinaperspectives.417 This text was automatically generated on 28 October 2019. © All rights reserved The Debate Between Liberalism and Neo-Leftism at the Turn of the Century 1 The Debate Between Liberalism and Neo-Leftism at the Turn of the Century Chen Lichuan EDITOR'S NOTE Translated from the French original by Nick Oates 1 From the beginning of the 1980s to the middle of the 1990s, three movements took centre stage on the Chinese intellectual scene: radicalism, conservatism and liberalism. This article sets out to retrace the debate between liberalism and neo-leftism by relying exclusively on the polemical texts of the Chinese writers1. How can we present an intellectual debate that is a process of questioning and clarification and that does not arrive at a consensual conclusion? How can we render intelligible the concepts debated in extracts from the original texts? How can we evaluate the impact that this debate has had on a society undergoing a profound transformation? These are just some of the difficulties with which we were confronted. -

The Chinese Liberal Camp in Post-June 4Th China

The Chinese Liberal Camp [/) OJ > been a transition to and consolidation of "power elite capital that economic development necessitated further reforms, the in Post-June 4th China ism" (quangui zibenzhuyr), in which the development of the provocative attacks on liberalism by the new left, awareness of cruellest version of capitalism is dominated by the the accelerating pace of globalisation, and the posture of Jiang ~ Communist bureaucracy, leading to phenomenal economic Zemin's leadership in respect to human rights and rule of law, OJ growth on the one hand and endemic corruption, striking as shown by the political report of the Fifteenth Party []_ social inequalities, ecological degeneration, and skilful politi Congress and the signing of the "International Covenant on D... cal oppression on the other. This unexpected outcome has Economic, Social and Cultural Rights" and the "International This paper is aa assessment of Chinese liberal intellectuals in the two decades following June 4th. It provides an disheartened many democracy supporters, who worry that Covenant on Civil and Political Rights."'"' analysis of the intellectual development of Chinese liberal intellectuals; their attitudes toward the party-state, China's transition is "trapped" in a "resilient authoritarian The core of the emerging liberal camp is a group of middle economic reform, and globalisation; their political endeavours; and their contributions to the project of ism" that can be maintained for the foreseeable future. (3) age scholars who can be largely identified as members of the constitutional democracy in China. However, because it has produced unmanageably acute "Cultural Revolution Generation," including Zhu Xueqin, social tensions and new social and political forces that chal Xu Youyu, Qin Hui, He Weifang, Liu junning, Zhang lenge the one-party dictatorship, Market-Leninism is not actu Boshu, Sun Liping, Zhou Qiren, Wang Dingding and iberals in contemporary China understand liberalism end to the healthy trend of politicalliberalisation inspired by ally that resilient. -

Copyright by Yue Ma 2004

Copyright by Yue Ma 2004 The Dissertation Committee for Yue Ma Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Catastrophe Remembered by the Non-Traumatic: Counternarratives on the Cultural Revolution in Chinese Literature of the 1990s Committee: Sung-sheng Yvonne Chang, Supervisor Margherita Zanasi Avron Boretz Qing Zhang Ban Wang The Catastrophe Remembered by the Non-Traumatic: Counternarratives on the Cultural Revolution in Chinese Literature of the 1990s by Yue Ma, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2004 Dedication To my personal savior, Jesus Christ, who touched my life and sent me the message that love never fails. To the memory of my father, who loved me and influenced my life tremendously. To my mother, who always believes in me, encourages me, supports me, and feels proud of me. To my husband, Chu-ong, whose optimistic attitude towards life affects people around him and brings hope and happiness to our family. To my precious son, Daniel (Dou Dou), whose heavenly smiles never fail to melt my heart. Special love to a special you. Acknowledgements I would like to offer a special thanks to Dr. Yvonne Sung-sheng Chang, my academic advisor, who has supervised my study during the past six years and helped me in numerous ways. My appreciation also goes to Dr. Margherita Zanasi and Dr. Avron Boretz. Taking your classes and having opportunities to discuss various questions with you have been inspiring and rewarding experiences for me. -

MA Thesis Yu-Hsuan

The University of Chicago The New Left vs. Liberal Debate in China: How Ideology Shapes the Perception of Reality By Yu-Hsuan Sun July 2021 A paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Masters of Arts Degree in the Masters of Arts Program in the Social Sciences (MAPSS) Faculty Advisor: Marco Garrido Preceptor: Wen Xie Abstract: The tragic June 4th Crackdown on the Tiananmen Student Movement dealt a devastating blow to the hope of China’s democratization. In the 1980s, the majority of young Chinese students expressed overwhelming support for the democracy movement and the New Enlightenment thought trend which preceded the 1989 protests. The homogeneity of the 80s intellectual sphere, however, is a stark contrast to the intense debate between the “New Left” and “Liberal” camps in China which began in the late 1990s. My paper seeks to answer the question: “Why did China’s intellectual homogeneity dissolve so quickly in the 90s?” And more importantly, “What is at stake in those debates between intellectual camps?” To answer these questions, I argue that ideological differences among Chinese intellectuals fundamentally change their perception of China’s post-1989 reality. After the Tiananmen Movement, Deng Xiaoping intensified China’s economic reforms as an answer to both the internal and external crises to his political power after June 4th. While this new wave of reforms brought about unprecedented economic growth and commerce in China, it also created looming social problems such as inequality and corruption. However, these social issues generated polarizing responses from Chinese intellectuals who offered contradicting explanations to these social and economic issues. -

Composing, Revising, and Performing Suzhou Ballads: a Study of Political Control and Artistic Freedom in Tanci, 1949-1964

Composing, Revising, and Performing Suzhou Ballads: a Study of Political Control and Artistic Freedom in Tanci, 1949-1964 by Stephanie J. Webster-Cheng B.M., Lawrence University, 1996 M.A., University of Pittsburgh, 2003 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Music Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2008 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH MUSIC DEPARTMENT This dissertation was presented by Stephanie Webster-Cheng It was defended on [author‟s name] October 31, 2008 and approved by Mark Bender, Associate Professor, East Asian Languages and Literature, Ohio State University Xinmin Liu, Assistant Professor, East Asian Languages and Literature Wenfang Tang, Associate Professor, Political Science Andrew Weintraub, Associate Professor, Music Akin Euba, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Music, Music Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung, Professor of Music, Music ii Copyright © by Stephanie J. Webster-Cheng 2008 iii Composing, Revising, and Performing Suzhou Ballads: a Study of Political Control and Artistic Freedom in Tanci, 1949-1964 Stephanie J. Webster-Cheng, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2008 This dissertation explores the dynamics of political control of the arts and artistic freedom in the musical storytelling art of Suzhou tanci between 1949 and 1964, years marked by extensive revision of traditional performance repertoire, widespread creation of new, contemporary-themed stories, and composition of boldly innovative ballad music. I examine four stories and ballads either composed or revised during this time, looking broadly at the role of the State in the creative process. I consider the role of high-ranking officials whose personal comments to artists shaped their creative processes, and the role of societal political pressure placed on artists through political movements and shifting trends in the dramatic arts. -

Your Show's Been Cut: the Politics of Intellectual Publicity in China's

YOUR SHOW’S BEEN CUT: THE POLITICS OF INTELLECTUAL PUBLICITY IN CHINA’S BRAVE NEW MEDIA WORLD YUEZHI ZHAO Abstract 118 - This paper examines the increasingly important com- Yuezhi Zhao is Professor munication politics between the media and intellectual and Canada Research fi elds in China’s brave new media world. It starts by outlin- Chair in Political Economy ing key factors that have shaped the evolving post-1989 of Global Communication politics of intellectual publicity in China. It then describes at Simon Fraser University, a deep “liberal versus new left” division within the Chinese and Changjiang Scholar intellectual fi eld and the ascending power of theNanfang Chair Professor at Weekend and liberal intellectual alliance within China’s the Communication CCP-controlled media system. In a subsequent case study, University of China, Beijing; I analyse how the destructive logics of media sensational- e-mail: [email protected]. ism, academic corruption, ideological polarisation, and “lib- eral media instrumentalism” have intersected to spectacu- larise intellectual in-fi ghts and distract both the media and the academy from engaging the public around the urgent Vol.19 (2012), No. 2, pp. 101 2, pp. (2012), No. Vol.19 political economic and social issues of the day. 101 Introduction Chinese media and intellectuals have been extensively studied in their respec- tive relationships vis-à-vis the Chinese state, and more recently, in terms of how they each have been caught “between state and market” or “the party line and the bo om line” (Zhao 1998). There are also studies of prominent Chinese intellectuals working in the media during the Mao era, most notably Deng Tuo, who served as an editor-in-chief of the People’s Daily during the Mao era (Cheek 1997). -

WHY DID the CULTURAL REVOLUTION END? Han

WHY DID THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION END? Han Shaogong Translated by Adrian Thieret Mainstream society has seemingly reached a common understanding regarding the causes of the Cultural Revolution. Some people men- tion China’s tradition of autocracy; others mention the infl uence of Stalinism and trace the Cultural Revolution back to the achievements and failures of the Russian and French revolutions. However, most people do not have the patience to bother with these explanations and instead simply attribute the Cultural Revolution to a “power struggle” or “nationwide madness.” Here, let us set aside this issue and ask a different question: why did the Cultural Revolution end? As we have refl ected upon the beginnings of the Cultural Revolu- tion, we cannot avoid its conclusion. As there are reasons for the birth of the Cultural Revolution, so must there be reasons for its end. As certain Western scholars have noted, tyrannical governments never exit the historical stage of their own accord, rather, they must be force- fully removed—this is the logic behind the present Iraq War initiated by the United States and United Kingdom. However, the Cultural Revolution, usually considered an example of tyranny, seems to exist outside of this logic. It was not ended by widespread revolt, as was the Qing dynasty, nor was it ended by the occupation of foreign armies, as was the Japanese government in World War Two. The Gang of Four was crushed basically without bloodshed, and the entire conclusion of Cultural Revolution was relatively peaceful. The third plenary meeting of the 11th Central Committee of the CCP, which marked the end of Cultural Revolution, completed the transfer of power in merely one or two sessions, relying only on a debate regarding “standards of truth.” The transition went smoothly. -

The Recasting of Chinese Socialism: the Chinese New Left Since 2000 China Information 2018, Vol

CIN0010.1177/0920203X18760416China InformationShi et al. 760416research-article2018 Research dialogue chiINFORMATION na The recasting of Chinese socialism: The Chinese New Left since 2000 China Information 2018, Vol. 32(1) 139 –159 © The Author(s) 2018 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Shi Anshu https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203X18760416DOI: 10.1177/0920203X18760416 Tsinghua University, China journals.sagepub.com/home/cin François Lachapelle University of British Columbia, Canada Matthew Galway University of British Columbia, Canada Abstract In post-Mao China, a group of Chinese intellectuals who formed what became the New Left (新左派) sought to renew socialism in China in a context of globalization and the rise of social inequalities they associated with neo-liberalism. As they saw it, China’s market reform and opening to the world had not brought greater equality and prosperity for all Chinese citizens. As part of China Information’s research dialogue on the intellectual public sphere in China, this article provides a historical survey of the development of the contemporary Chinese New Left, exploring the range of ideas that characterized this intellectual movement. It takes as its focus four of the most prominent New Left figures and their positions in the ongoing debate about China’s future: Wang Shaoguang, Cui Zhiyuan, Wang Hui, and Gan Yang. Keywords contemporary China, market reform, end of history, New Left, Chinese socialism, Maoism, democracy, statism Corresponding author: Shi Anshu, School of Humanities, Tsinghua University, Haidian District, Beijing, 100084, China. Email: [email protected] 140 China Information 32(1) By the Cold War’s end, people suddenly discovered ‘the end of history’, and there appeared to be no alternative to the liberal economic order of or as envisaged by Francis Fukuyama. -

After Revolution : Reading Rousseau in 1990S China

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. After revolution : reading Rousseau in 1990s China van Dongen, Els; Chang, Yuan 2017 van Dongen, E., & Chang, Y. (2017). After revolution : reading Rousseau in 1990s China. Contemporary Chinese Thought, 48(1), 1‑13. doi:10.1080/10971467.2017.1383805 https://hdl.handle.net/10356/143782 https://doi.org/10.1080/10971467.2017.1383805 This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Contemporary Chinese Thought on 14 Dec 2017, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/10971467.2017.1383805. Downloaded on 29 Sep 2021 15:15:43 SGT The final version of this article was published in Contemporary Chinese Thought 48.1 (2017): 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10971467.2017.1383805 Introduction After Revolution: Reading Rousseau in 1990s China Els van Dongen and Yuan Chang Abstract This article reviews Zhu Xueqin’s (b. 1952) writings on Jean-Jacques Rousseau against the background of the reception of Rousseau in China since the late nineteenth century. Rousseau was both an advocate and critic of the Enlightenment, and his work hence appealed to many Chinese intellectuals who struggled with the conundrum of how to modernize. During the late nineteenth century, Chinese supporters of Rousseau drew on his work to defend the viability of revolution. During the 1990s, following the tragedy of Tiananmen and the decline of socialism, Rousseau served to reflect on China’s twentieth-century trajectory and the disastrous political consequences of collective moral idealism. For Zhu Xueqin, a key question was: Why were the French Revolution and the Cultural Revolution so similar? Rousseau and the Double-Edged Sword of Modernity In the history of modern Western political thought, few have managed to achieve the fame and influence of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). -

Yongyi Song, Editor-In-Chief: China and the Maoist Legacy: the 50Th Anniversary of the Cultural Revolution Heng Ge

Journal of East Asian Libraries Volume 2017 | Number 165 Article 14 10-2017 Book Review: Yongyi Song, Editor-in-Chief: China and the Maoist Legacy: The 50th Anniversary of the Cultural Revolution Heng Ge Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Ge, Heng (2017) "Book Review: Yongyi Song, Editor-in-Chief: China and the Maoist Legacy: The 50th Anniversary of the Cultural Revolution," Journal of East Asian Libraries: Vol. 2017 : No. 165 , Article 14. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal/vol2017/iss165/14 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of East Asian Libraries by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of East Asian Libraries, No. 165, Oct. 2017 Yongyi Song, Editor-in-Chief:China and the Maoist Legacy: The 50th Anniversary of the Cultural Revolution 文革五十年:毛泽东遗产和当代中国. Hong Kong and New York: Mirror Books, 2016, 2 vols. The 50th anniversary of the Chinese Cultural Revolution in 2016 inspired several commemorative seminars and conferences in Germany, France, Japan, Hong Kong and the United States. However, only one such commemorative event held in Los Angeles and UC Riverside entitled China and Mao’s Legacy: Commemoration of the 50th Anniversary of the Cultural Revolution produced a two-part conference volume entitled China and the Maoist Legacy: The 50th Anniversary of the Cultural Revolution. Complete with nearly one million Chinese characters and edited by Yongyi Song, a leading Cultural Revolution scholar and one of the chief organizers of the conference, this conference volume is a significant contribution to the existing literature on the Cultural Revolution.