Power, Pleasure, and Pollution: Water Use in Pre-Industrial Nuremberg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Office Market Profile

Office Market Profile Nuremberg | 4th quarter 2019 Published in February 2020 Nuremberg Development of Main Indicators High take-up thanks to large-scale lettings Nuremberg’s off ice space market remained a sought-aft er business location. Positive net absorption confi rmed the steady growth of the Franconian city. The market was char- acterised by strong demand for off ice space, but also by low supply. For the fi rst time, there was a clear alignment of two submarkets in terms of the prime rent. In 2019, 133,600 sqm of off ice space was taken up on the Nuremberg off ice space market - almost double the previous this size category was concluded by Design Off ices GmbH in year’s result of 67,300 sqm and the third-best result within the the City Centre Fringe submarket (approx. 10,000 sqm). last ten years aft er 2016 (142,000 sqm) and 2017 (137,900 sqm). This strong performance was attributable to fi ve leases The Nuremberg real estate market remains a sought-aft er in the large-scale size category. With a total volume of 76,500 business location and continues to expand. Over the past 12 sqm, these lettings accounted for more than half of the overall months, this has been evident from the net absorption fi g- result. By far, the largest letting was concluded by the City of ure which has improved by 59,000 sqm in terms of the vol- Nuremberg in “The Q” (approx. 42,000 sqm). Another lease in ume of occupied off ice space. -

Internationally Coordinated Management Plan 2015 for the International River Basin District of the Rhine

Internationally Coordinated Management Plan 2015 for the International River Basin District of the Rhine (Part A = Overriding Part) December 2015 Imprint Joint report of The Republic of Italy, The Principality of Liechtenstein, The Federal Republic of Austria, The Federal Republic of Germany, The Republic of France, The Grand Duchy of Luxemburg, The Kingdom of Belgium, The Kingdom of the Netherlands With the cooperation of the Swiss Confederation Data sources Competent Authorities in the Rhine river basin district Coordination Rhine Coordination Committee in cooperation with the International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine (ICPR) Drafting of maps Federal Institute of Hydrology, Koblenz, Germany Publisher: International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine (ICPR) Kaiserin-Augusta-Anlagen 15, D 56068 Koblenz P.O. box 20 02 53, D 56002 Koblenz Telephone +49-(0)261-94252-0, Fax +49-(0)261-94252-52 Email: [email protected] www.iksr.org Translation: Karin Wehner ISBN 978-3-941994-72-0 © IKSR-CIPR-ICBR 2015 IKSR CIPR ICBR Bewirtschaftungsplan 2015 IFGE Rhein Contents Introduction .................................................................................. 6 1. General description .............................................................. 8 1.1 Surface water bodies in the IRBD Rhine ................................................. 11 1.2 Groundwater ...................................................................................... 12 2. Human activities and stresses .......................................... -

Nobles and Nuremberg's Churches

Durham E-Theses Relations between Townspeople and Rural Nobles in late medieval Germany: A Study of Nuremberg in the 1440s POPE, BENJAMIN, JOHN How to cite: POPE, BENJAMIN, JOHN (2016) Relations between Townspeople and Rural Nobles in late medieval Germany: A Study of Nuremberg in the 1440s, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11492/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Relations between Townspeople and Rural Nobles in late medieval Germany A Study of Nuremberg in the 1440s Benjamin John Pope Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History, Durham University 2015 1 CONTENTS 1. Introduction . 7 The Medieval Debate. 9 ‘Not exactly established’: Historians, Towns and Nobility. .18 Liberals and Romantics . .20 The ‘Crisis’ of the Nobility . 25 Erasing the Divide . -

I University Microfilms, a XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan S I

71 - 27,439 BUCK, Lawrence Paul, 1944- THE CONTAINMENT OF CIVIL INSURRECTION: NURNBERG AND THE PEASANTS' REVOLT, 1524-1525. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 History, medieval i University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan s i :. Q Copyright by Lawrence Paul Buck 1971 THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE CONTAINMENT OF CIVIL INSURRECTION: NURNBERG AND THE PEASANTS* REVOLT, 1524-1525 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lawrence Paul Buck, B.A., M.A, jjg jjg 5*5 The Ohio State University 1971 Approved by Department of History PLEASE NOTE: Some pages have indistinct print. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The research for this dissertation was completed - while I was a Fulbright Graduate Fellow in Germany. I would like to acknowledge my appreciation to Dr. Gerhard Hirschmann, Director of the Nttrnberg City Archive, and to Dr. Otto Puchner, Director of the Bavarian State Archive, Nttrnberg. Both men were very generous in opening to me the vast sources in their care. I also wish to thank my family and my friends for their continual encouragement. I am deeply indebted to my adviser, Professor Harold J. Grimm, who has assisted me in every aspect of this work, and whose example as a scholar and teacher has stood as a constant source of inspiration for me. ii VITA October 6, 1944 Born - Pittsburg, Kansas 1966*......... B.A., Wichita State University, Wichita, Kansas 1966-196 7..... Woodrow Wilson Fellow, Department of History, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1967*..•••••••• M.A., The Ohio State University Columbus, Ohio 1967-1969*••••• NDEA Fellow, Department of History, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1969-1970 ,... -

Xerox University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, die quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

A Journal of German-American History Published by the Society for the History of the Germans in Maryland

A JOURNAL OF GERMAN-AMERICAN HISTORY Cover: Deutsches Haus (ca. 1925) Collection of the Maryland Historical Society VOLUME XLI 1990 A JOURNAL OF GERMAN-AMERICAN HISTORY PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY OF THE GERMANS IN MARYLAND RANDALL DONALDSON KLAUS WUST CO-EDITORS BALTIMORE, MARYLAND COPYRIGHT 1990 THE SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY OF THE GERMANS IN MARYLAND P.O. Box 22585 BALTIMORE, MARYLAND 21203 ISSN: 0148-7787 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE EDITORIAL STATEMENT ................................................................................................ 4 MEMBERS AND OFFICERS .............................................................................................. 5 OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY, 1886-1990 ............................................................................. 7 INVITATION ............................................................................................................... 9 FROM THE EDITOR ..................................................................................................... 11 A SALUTE TO THE GERMAN-AMERICAN BUSINESS ENTERPRISES OF BALTIMORE By WILLIAM H. McCLAIN ............................................................................... 13 MAJOR GENERAL THE BARON JOHANNES DE KALB: A FORGOTTEN MARYLAND PATRIOT By GERARD WM.WITTSTADT, SR ..................................................................... 17 THE GERMANTOWN PROTEST AND AFRO-GERMAN RELATIONS IN PENNSYLVANIA AND MARYLAND BEFORE THE CIVIL WAR By LEROYT. HOPKINS .................................................................................. -

Fließgewässer in Nürnberg

Inhaltsverzeichnis 0. Erläuterung von Abkürzungen und Fachbegriffen 1 1. Sachverhalt 3 2. Grundsätzliches 3 3. Überblick über die Fließgewässer dritter Ordnung in Nürnberg 3 4. Die Fließgewässer im Rahmen der Planung und des Ökokontos 4 5. Gewässerpflege und Gewässerunterhalt 5 6. Beteiligung Stadtentwässerung und Umweltanalytik Nürnberg 9 am Gewässerunterhalt 7. Anthropogene Einflüsse auf die Gewässer III. Ordnung 9 7.1 Konflikte aufgrund der allgemeinen Siedlungs- und 9 Planungstätigkeit 7.1.1 Inanspruchnahme von Gewässerflächen 9 7.1.2 Einleitung von Gewässern in die Kanalisation 10 7.2 Konflikte mit Grundstückseigentümern 11 7.3 Hochwasser und Überschwemmungsgebiete 13 8. Belastungen der Gewässer durch Einleitungen 17 8.1 Verbesserung der Gewässergüte und Ergebnisse der 17 biologischen und chemischen Untersuchungen 8.2 Die Entwicklung der Gewässergüte im Raum Nürnberg 19 8.3 Gewässergüte einzelner Gewässer 20 8.3.1 Langwassergraben 20 8.3.2 Bucher Landgraben 22 8.3.3 Fischbach 24 8.3.4 Goldbach 25 8.3.5 Gänseried- und Ludergraben 25 8.3.6 Entengraben, Eichenwaldgraben 25 und Gaulnhofener Graben 8.3.7 Kothbrunngraben 26 8.3.8 Gründlach (Gewässer II. Ordnung) 26 9. Neuerungen durch die Wasserrahmenrichtlinie 27 10. Resümee 28 Anlagen 1. Reduzierung der entlasteten / eingeleiteten Wassermengen 30 und Frachten 2. Definition der biologischen Gewässergüte 32 3. Verhältnis der genehmigten Entlastungswassermengen 33 zur Mittelwasserführung der Gräben 4. Genehmigte Entlastungswassermengen 34 Gewässer III. Ordnung Bericht über den Zustand kleiner -

7 Weiherlandschaft Im Volkspark Dutzendteich

7 Weiherlandschaft im Volkspark Dutzendteich Zur Weiherlandschaft zählen neben den beiden Dutzend- teichen die beiden Nummernweiher, der Flachweiher und der Silbersee. Der große Dutzendteich wird heute gern für den Wassersport genutzt, der kleine Dutzendteich und die Weiher haben einen eher naturnahen Charakter. Neben dem Langsee ist der kleine Dutzendteich das ein- zige Gewässer in Nürnberg, in dem das Baden ofiziell erlaubt ist. Der Dutzendteich wurde wahrscheinlich im 13. Jahrhun- dert durch Aufstauung des Langwassers und weiterer kleinerer Bäche künstlich angelegt und diente der Was- serspeicherung und der Fischzucht. Der Dutzendteich und das umliegende Gelände haben eine wechselvolle Geschichte. Bereits im 17. Jahrhundert war der Dut- zendteich ein beliebtes Auslugsziel der Nürnberger, die Landes-, Industrie-, Gewerbe- und Kunstausstellung und die Eröffnung des ersten stadteigenen Tiergartens auf dem Gelände des heutigen Volksfestplatzes folgten. Östlich an den Volkspark angrenzend wurde zwischen 1926-1928 ein Sportpark angelegt. Das NS-Regime überprägte das Dutzendteichgelände und den Luitpoldhain mit den Plänen zum NS-Partei- tagsgelände sehr stark. Der Dutzendteich wurde durch den Bau der großen Straße in den kleinen und großen Dutzendteich geteilt. Die Baugrube des geplanten Deut- schen Stadions bildet heute den Silbersee. Nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg konnte sich das Dutzend- teichgelände wieder zu einem Naherholungsgebiet ent- wickeln und fand eine Aneignung des Freiraumes statt. Noch heute sind die Spuren der wechselvollen Geschich- te auf dem Areal des Volksparks Dutzendteich ablesbar. Neben den noch erhaltenen baulichen Anlagen der NS- Zeit liegen die vielfältigen Freiraumnutzungen scheinbar ungeordnet nebeneinander. Der Volkspark Dutzendteich ist heute ein großzügiger Erholungsraum für die angrenzenden Quartiere und ein beliebtes Auslugsziel für den Wassersport. -

Germans Displaced from the East: Crossing Actual and Imagined Central European Borders, 1944-1955

GERMANS DISPLACED FROM THE EAST: CROSSING ACTUAL AND IMAGINED CENTRAL EUROPEAN BORDERS, 1944-1955 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Amy A. Alrich, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee Approved by Professor Alan Beyerchen, Advisor Professor Birgitte Soland _______________________ Professor Robin Judd Advisor Department of History Copyright by Amy A. Alrich 2003 ABSTRACT At the end of World War II the Allies demilitarized, divided, and democratized Germany. The dismantling of Germany involved setting up four zones and eventually two states, the Federal Republic and German Democratic Republic (GDR), and also giving large German territories to Poland and the Soviet Union, which required the initiation of a forced population transfer of the Germans who lived in those areas. Whether they fled as the Soviet troops advanced, or faced the postwar expulsions arranged by the Allies, the majority of Germans from the Eastern territories, approximately 12 million altogether, survived the arduous trek West. Roughly 8 million ended up in West Germany; 4 million went to the GDR. This dissertation comparatively examines the postwar, post-flight experiences of the German expellees in the Federal Republic and GDR in the late 1940s and 1950s. This analysis involves an examination of four categories of experience: official images of the expellees, their self-images, their images as outsiders, and expellees' reaction to these outsider-images. The two Germanies' expellee policies differed dramatically and reflected their Cold War orientations. West Germany followed a policy of expellee-integration, which highlighted their cultural differences and encouraged them to express their uniqueness. -

Nobles and Nuremberg's Churches

Durham E-Theses Relations between Townspeople and Rural Nobles in late medieval Germany: A Study of Nuremberg in the 1440s POPE, BENJAMIN, JOHN How to cite: POPE, BENJAMIN, JOHN (2016) Relations between Townspeople and Rural Nobles in late medieval Germany: A Study of Nuremberg in the 1440s, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11492/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Relations between Townspeople and Rural Nobles in late medieval Germany A Study of Nuremberg in the 1440s Benjamin John Pope Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History, Durham University 2015 1 CONTENTS 1. Introduction . 7 The Medieval Debate. 9 ‘Not exactly established’: Historians, Towns and Nobility. .18 Liberals and Romantics . .20 The ‘Crisis’ of the Nobility . 25 Erasing the Divide . -

Final Application Nuremberg Green Capital City 2012/2013

FINAL APPLICATION NUREMBERG Green Capital City 2012/ 2013 Award year Award year: Either 2012 or 2013 Municipality: Name of municipality: Nuremberg Country: Germany Size of municipality (km²): 186 Number of inhabitants in municipality: 495459 Name of mayor: Dr. Ulrich Maly Address of mayor's office: Stadt Nürnberg Rathausplatz 2 90403 Nürnberg Contact info Contact person: Dr. Susanne Schimmack Address: Umweltreferat Hauptmarkt 18 90403 Nürnberg Telephone: 0049-911-2315942 Fax: 0049-911-2313391 E-mail: [email protected] - 1 - 1. Local contribution to global climate change 1a. Describe the present situation and developments over the last five to ten years regarding (max. 1,000 words): 1. Total CO2 equivalent per capita, including emissions resulting from use of electricity; 2. CO2 per capita resulting from use of natural gas; 3. CO2 per capita resulting from transport; 4. Gram of CO2 per kWh used. 1.1. The present situation and developments over the last five to ten years The City of Nuremberg has put considerable effort into its municipal climate policy and has experienced some success. The City attaches great importance to energy issues. Increased use of renewable forms of energy and high energy efficiency are two tools to fight climate change. Since 2000 Nuremberg has been a member of the Climate Alliance of European Cities, the largest European city network for climate protection. As a member of the Climate Alliance, Nuremberg has committed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions continuously. Since 2009 Nuremberg, has also been a member of the Covenant of Mayors. Numerical values are available for the year 2008. -

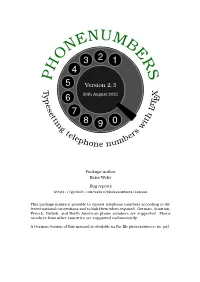

Typesetting Telephone Numbers with Latex

ENUMB N E O 3 2 1 R H 4 S P 5 Version 2.3 T y 20th August 2021 X p 6 E e T s A L e 7 t h t t in 8 0 i g 9 w te rs lep be hone num Package author Keno Wehr Bug reports https://github.com/wehro/phonenumbers/issues This package makes it possible to typeset telephone numbers according to dif- ferent national conventions and to link them when required. German, Austrian, French, British, and North American phone numbers are supported. Phone numbers from other countries are supported rudimentarily. A German version of this manual is available in the file phonenumbers-de.pdf. Contents 1 Quick Start 4 1.1 Germany ................................. 4 1.2 Austria ................................... 4 1.3 France ................................... 5 1.4 United Kingdom ............................. 5 1.5 North America .............................. 6 1.6 Other Countries ............................. 6 2 General Principles 7 2.1 Basic Ideas of the Package ....................... 7 2.2 Commands ................................ 7 2.3 Linking of Phone Numbers ....................... 8 2.4 Options .................................. 9 2.5 Invalid Numbers ............................. 11 2.6 Licence .................................. 11 3 German Phone Numbers 12 3.1 Structure of the Numbers ........................ 12 3.2 Options .................................. 13 3.3 Invalid Numbers ............................. 14 4 Austrian Phone Numbers 16 4.1 Structure of the Numbers ........................ 16 4.2 Options .................................. 17 4.3 Invalid Numbers ............................. 18 5 French Phone Numbers 20 5.1 Scope ................................... 20 5.2 Structure of the Numbers ........................ 20 5.3 Options .................................. 22 5.4 Invalid Numbers ............................. 23 6 British Phone Numbers 24 6.1 Scope ................................... 24 6.2 Structure of the Numbers .......................