Exceptions to Copyright in Russia and the “Fair Use” Doctrine European Audiovisual Observatory, Strasbourg, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Netease Cloud Music and Big Hit Entertainment Team up to Launch BTS' Song Catalog

NetEase Cloud Music and Big Hit Entertainment team up to launch BTS' song catalog HANGZHOU, China, May 4, 2018 /PRNewswire/ -- NetEase Cloud Music, China's leading music platform, entered into a partnership agreement with South Korea-based Big Hit Entertainment, whereby the Chinese platform will launch BTS' repertoire of songs on the platform. Big Hit Entertainment, a South Korea-based entertainment company focused on music, represents and manages BTS, the company's leading all-male group, which debuted in 2013. BTS is comprised of seven male vocalists: RM, Jin, SUGA, j-hope, Jimin, V and Jung Kook. BTS, the abbreviation for Bangtan Sonyeondan, also stands for Bulletproof Boys and Beyond The Scene. Since the group's first appearance, they have received several major awards at music festivals held in South Korea as well as some international events. In 2017, they were named Top Social Artist by Billboard Music Awards, garnering the group worldwide attention. This February, they were again listed as an award candidate, competing with international superstars. Recently, NetEase Cloud Music launched BTS' widely popular catalog of songs on its platform, including MIC Drop (Steve Aoki Remix) (Feat. Desiigner), DNA, Spring Day, Not Today, Blood Sweat & Tears, Fire, Dope and I need U. In addition to music copyright, NetEase Cloud Music will cooperate with Big Hit Entertainment on artist and music promotion, marking the start of a close collaboration that will cover all aspects of the music business. The two parties look forward to jointly driving the popularity of music artists and their works via multiple channels, while offering higher quality music services to wider audiences. -

Brownmark Vs Comedy Central PRESS RELEASE

PRESS RELEASE Brownmark Films, LLC Contact: Bobby Ciraldo, Andrew Swant FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Phone: 414-263-4180 E-Mail: [email protected] Attorney of Record: Caz McChrystal Phone: 715-346-4660 BROWNMARK FILMS VS. VIACOM, ET AL What What (In the Butt) Producers File Copyright Infringement Case Against South Park November 12th, 2010 - Milwaukee, WI -- Brownmark Films, the two-person production company behind the viral YouTube video What What (In the Butt), filed a copyright infringement lawsuit today against Viacom International Inc, Comedy Partners (known as Comedy Central), Paramount Pictures Corporation, MTV Networks, and South Park Digital Studios LLC. Brownmark Films claim that their music video, a comically innocuous portrayal of the song's salacious lyrics, was used in an episode of Comedy Central's South Park without permission. The episode, entitled "Canada on Strike" contains a shot-for-shot recreation of significant portions of the What What (In the Butt) video. The episode satirizes the 2007-2008 Writers Guild strike and illegally appropriated Brownmark Films' video in order to do so. While Brownmark Films was never contacted by Comedy Central for use of the video, it is believed that the song "What What (In the Butt)" was legally licensed through its respective copyright owner. Unlike most music videos, which are financed by the artist's record label to be used as a promotional tool for the recording, What What (In the Butt) was produced jointly by Brownmark Films and Samwell, then an unsigned musician with an unpublished song. While primarily intended as a comedic art piece, Brownmark Films created the video with hopes of licensing it for wider distribution. -

Tesis726.Pdf

i REGLAMENTO DE LA PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD JAVERIANA ARTÍCULO 23 “La Universidad no se hace responsable por los conceptos emitidos por los alumnos en sus trabajos de grado, solo velará porque no se publique nada contrario al dogma y la moral católicos y porque el trabajo no contenga ataques y polémicas puramente personales, antes bien, se vean en ellas el anhelo de buscar la verdad y la justicia”. ii Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Facultad de comunicación y lenguaje Carrera de comunicación social Énfasis audiovisual Realidades paralelas Diseño de una miniserie para web 2.0 en narrativa paralela TRABAJO DE GRADO PARA OPTAR POR EL TÍTULO DE COMUNICADOR SOCIAL CON ÉNFASIS AUDIOVISUAL PRESENTADO POR: Rafael Andrés Becerra Saldaña DIRECTOR/ASESOR: Víctor Hugo Valencia Aristizábal BOGOTÁ, MAYO DE 2011 iii Esta página es dejada en blanco intencionalmente iv Agradecimientos – Dedicatoria considerado como parte de mi familia, también a Diana Rojas y a María Fernanda Granados, las adoró con todas mis fuerzas, a Pamela Morales por ser un amiga de verdad… No puedo dejar de pensar que mientras escribo este texto mi A pesar de varios malos ratos, la universidad me ha llenado de padre sufre los efectos de un cáncer desgarrador y una personas valiosas por las cuales se realiza este trabajo y a quienes quimioterapia llena de dolorosos efectos secundarios y que a espero siempre llevar en aquellos recuerdos que se almacenan en pesar de esto nunca ha dejado de trabajar para poder darnos a mi el corazón, muchas gracias Ricardo Suárez, Oneris Rico, Liliana hermana, mi madre y a mi todo lo que siempre hemos Avendaño, Sebastián Kowoll, Daniela Gómez, Daniela Vargas, necesitado, este trabajo te lo dedico a ti papá. -

Run Bts Bingo

www.cactuspop.com RUN BTS BINGO The same RM breaks They play rock Jimin falls over scene is Hand holding something paper scissors laughing replayed 3 times Squeaky sound Someone sings V shows his Jin blows a They eat effect a BTS song artistic side kiss something Jin does Someone gets Jungkook J-Hope dances windscreen BTS roasted by the shows his Free Space wiper laugh other members strength Suga falls Jin gets angry BTS are nice to Someone Jin cracks a asleep and yells staff speaks satoori dad joke Someone Big Hit censors The subs seem Someone yells Worldwide mentions someone’s like fake subs “woooaaahhh” handsome ARMY body RUN BTS BINGO Someone yells Squeaky sound The subs seem BTS are nice to Hand holding “woooaaahhh” effect like fake subs staff Jin does The staff Suga falls ㅋㅋㅋㅋㅋㅋㅋ windscreen change the J-Hope dances asleep wiper laugh ㅋㅋ rules Worldwide V shows his BTS Someone sings RM breaks handsome artistic side Free Space a BTS song something The same Jin gets angry They eat They play rock scene is Jin blows a and yells something paper scissors replayed 3 kiss times Big Hit censors Jungkook Someone Jimin falls over Jin cracks a someone’s shows his speaks satoori laughing dad joke body strength RUN BTS BINGO Jin blows a Someone sings Jin gets angry Someone yells Hand holding kiss a BTS song and yells “woooaaahhh” They play rock They eat Squeaky sound V shows his Jin cracks a paper scissors something effect artistic side dad joke The same Someone Someone gets The subs seem scene is mentions BTS roasted by the like fake subs Free -

BTS, Digital Media, and Fan Culture

19 Hyunshik Ju Sungkyul University, South Korea Premediating a Narrative of Growth: BTS, Digital Media, and Fan Culture This article explores the landscape of fan engagements with BTS, the South Korean idol group. It offers a new approach to studying digital participation in fan culture. Digital fan‐based activity is singled out as BTS’s peculiarity in K‐pop’s history. Grusin’s discussion of ‘premediation’ is used to describe an autopoietic system for the construction of futuristic reality through online communication between BTS and ARMY, as the fans are called. As such, the BTS’s live performance is experienced through ARMY’s premediation, imaging new identities of ARMY as well as BTS. The way that fans engage digitally with BTS’s live performance is motivated by a narrative of growth of BTS with and for ARMY. As an agent of BTS’s success, ARMY is crucial in driving new economic trajectories for performative products and their audiences, radically intervening in the shape and scope of BTS’s contribution to a global market economy. Hunshik Ju graduated with Doctor of Korean Literature from Sogang University in South Korea. He is currently a full‐time lecturer at the department of Korean Literature and Language, Sungkyul University. Keywords: BTS, digital media fan culture, liveness, premediation Introduction South Korean (hereafter Korean) idol group called Bulletproof Boy AScouts (hereafter BTS) delivered a speech at the launch of “Generation Unlimited,” United Nations Children’s Fund’s (UNICEF) new youth agenda, at the United Nations General Assembly in New York on September 24, 2018. In his speech, BTS’s leader Kim Nam Jun (also known as “RM”) stressed the importance of self-love by stating that one must love oneself wholeheartedly regardless of the opinions and judgments of others.1 Such a message was not new to BTS fans, since the group’s songs usually raise concerns and reflections about young people’s personal growth. -

Umberto Galimberti Ha Scritto

Il campo del “popolare”: definizioni e ri-definizioni di Claudio Bisoni Definizioni Da quando il concetto di “cultura popolare” emerge, verso la fine del Settecento, nei discorsi degli intellettuali intorno a ciò che noi oggi chiameremmo “cultura folk”, le definizioni di “popolare” susseguitesi nella storia sono state molte e hanno toccato ambiti eterogenei. La nozione di “cultura popolare” - assieme a termini connessi come “popolo”, “folla”, “massa”, “cultura di massa” ecc. - ha incontrato definizioni che non si sono limitate a essere numerose: sono anche state tutt’altro che innocenti o disinteressate. Nelle scienze politiche si tende a considerare - non a torto - la lotta intorno a ciò che è il popolo come uno dei tratti essenziali della politica stessa. Infatti - lo notava Stuard Hall - i modi in cui ci si appella al popolo come ragione giustificatrice dell’azione politica sono i più vari e includono anche Margaret Thatcher quando afferma che la “gente” non vuole il potere dei sindacati. È inutile soffermarsi sul fatto che la storia italiana recente è stata prodiga, in modo quasi insopportabile, di simili esempi. John Storey, in Cultural Theory and Popular Culture: an Introduction, si richiama a precedenti definizioni di Raimond Williams e a Stuard Hall per proporre una piccola lista di cosa si intende e si è inteso nel passato recente con i termini “popolare” e “cultura popolare”1. In primo luogo troviamo una definizione quantitativa: è popolare tutto ciò che “piace alla gente”, vale a dire, a più persone possibile. È senz’altro vero che si tratta di una definizione insoddisfacente: troppe cose e troppo diverse tra loro piacciono a molta gente. -

A Critical Discourse Analysis of Kim Namjoon's (Rm's) Speech

Jurnal Humaniora Teknologi p-ISSN: 2443-1842 Volume 5, Nomor 2, Oktober 2019 e-ISSN: 2614-3682 A CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF KIM NAMJOON’S (RM’S) SPEECH Uswatun Hasanah1), Alek Alek2), Didin Nuruddin Hidayat3*) Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta email*): [email protected] Abstract This research explores critical discourse analysis of a speech conveyed by Kim Namjoon (widely known as RM), the leader of BTS. The framework of analysis was based on M.A.K Halliday theory, Systematic Functional Grammar (SFG). This CDA study was employed to reveal the language, ideology and power. The data was collected from a six-minute speech by RM and analyzed qualitatively. The speech consisted of 784 words. The result showed that all processes types of transitivity system found in the speech with relational process as the most dominant process, followed by mental and behavioral process respectively. In addition, modality analysis result showed that the general tense use in the speech were simple present and simple past with the first and second pronoun as the participants, none of singular third person used in the speech. Last, May and Will took more often used in the speech compare with other modal auxiliaries. Keywords: Critical Discourse Analysis, RM’s Speech INTRODUCTION One of the approaches in discourse analysis study is Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA, hereafter). It emerged from the school of critical linguistics which drew upon Halliday’s systemic functional linguistics and theories of ideologies (Jahedi, Abdullah & Mukundan, 2014). CDA is one of branches of discourse analytical research which mainly explores about existence and role of social power in social situation or political situation. -

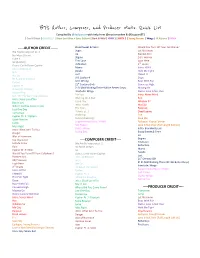

BTS Author, Composer, and Producer Stats

BTS Author, Composer, and Producer stats: Quick List Compiled By @dailyunnie with help from @musicmunkee & @SupportBTS 2 Cool 4 Skool | O!RUL8,2? | Skool Luv Affair + Spec. Edition | Dark & Wild | HYYH 1 | HYYH 2 | Young Forever | Wings | JP Albums | YNWA -----AUTHOR CREDIT------ Blood Sweat & Tears Would You Turn Off Your Cellphone? We Are Bulletproof pt. 2 Begin Let Me Know Lie Blanket Kick No More Dream Stigma 24/7 Heaven I Like It First Love Look Here Gil (hidden) Reflection 2nd Grade Outro: Circle Room Cypher Intro: O!RUL8,2? Mama Intro: HYYH Awake Hold Me Tight N.O We On Lost I Need U BTS Cypher 4 Dope If I Ruled The World Coffee Am I Wrong Boyz With Fun 21st Century Girls Converse High Cypher Pt. 1 Attack On Bangtan 2! 3! (Still Wishing There Will be Better Days) Moving On Interlude: Wings Outro: Love Is Not Over Satoori Rap Skit: On The Start Line (hidden) For You Intro: Never Mind Wishing On A Star Run Intro: Skool Luv Affair Boy In Luv Good Day Whalien 52 Intro: Youth Ma City Where Did You Come From? The Stars Baepsae Just One Day I Like It pt. 2 Dead Leaves Tomorrow Wake Up Fire Cypher Pt. 2: Triptych Spine Breaker Outro (Wake Up) Save Me Supplemental Story: YNWA Epilogue: Young Forever Jump Miss Right Not Today Love Is Not Over (Full Length Edition) Outro: Wings Intro: Boy Meets Evil Intro: What Am I To You Danger Spring Day Blood Sweat & Tears Lie War of Hormone Hip Hop Lover ----COMPOSER CREDIT---- Stigma First Love Let Me Know We Are Bulletproof pt. -

Pro Gradu Paronen

APPRAISAL IN ONLINE REVIEWS OF SOUTH PARK: A study of engagement resources used in online reviews. Master's thesis Tiina Paronen University of Jyväskylä Department of languages English August 2011 JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO Tiedekunta – Faculty Laitos – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Kielten laitos Tekijä – Author Tiina Paronen Työn nimi – Title APPRAISAL IN ONLINE REVIEWS OF SOUTH PARK: A study of engagement resources used in online reviews. Oppiaine – Subject Työn laji – Level englanti Pro gradu -tutkielma Aika – Month and year Sivumäärä – Number of pages elokuu 2011 76 Tiivistelmä – Abstract Tutkielman tarkoituksena on selvittää, millaisin kielellisin keinoin kirjoittaja voi ilmaista mielipiteitään ja arvioitaan verkkoarvosteluissa. Tutkielma pyrkii kuvailemaan keinoja, joilla kirjoittaja huomioi lukijan pyrkiessään omiin tavoitteisiinsa. Tutkielman tarkoituksena on myös tarkastella verkkoarvosteluja genre-analyysin näkökulmasta. Teoreettisesti ja metodologisesti tutkimus nojaa Martinin ja Whiten kehittelemään arvioimisen analyysiin (appraisal analysis). Tutkimusaineisto koostuu neljästätoista televisioanimaation verkkoarvostelusta. Verkkoarvosteluja tarkastellaan laadullisesti. Tutkimuksen tulokset osoittavat kirjoittajan kiinnittävän paljon huomiota suhteeseen lukijan kanssa, mikä ilmenee kirjoittajan käyttämistä kielellisistä keinoista. Tutkimuksen perusteella lukijan ja kirjoittajan suhde on kirjoittajalle vähintään yhtä tärkeää kuin kirjoittajan omien mielipiteiden ilmaisu. Tutkimuksen tulokset osoittavat, että kirjailija luo itselleen -

The Official BTS X Mattel Dolls Make Their Way to Fans at Toys"R"Us Canada Locations and Online

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The official BTS x Mattel dolls make their way to fans at Toys"R"Us Canada locations and online The BTS Idol Doll, pictured here, along with SUGA, V, Jin, Jung Kook, RM, Jimin, j-hope Idol Doll are available For pre-order on the Toys"R"Us Canada website For $29.99 plus applicable taxes and available for purchase in-store Sunday, July 28. TORONTO, July 25, 2019 – In anticipation of the release of Bring the Soul: The Movie, a documentary film about the South Korean boy band, BTS, the official BTS x Mattel dolls are soon to be available at Toys"R"Us locations across the country. The dolls are recreations of all seven artists V, SUGA, Jin, Jung Kook, RM, Jimin and j-hope, each sportinG their own siGnature style – wearinG the suit inspired by the iconic "Idol" music video. "We’re excited to offer our consumers this wonderful piece of contemporary South Korean pop culture and entertainment,” says Melanie Teed-Murch, president at Toys"R"Us Canada. “We’re pleased to expand our partnership with Mattel and offer these dolls in our stores. We are sure children and children at heart, as well as existinG and new fans of BTS, will enjoy these toys.” Each doll is 11" tall with rooted hair and has been authentically sculpted to the bandmate’s likeness. Each doll is sold separately and is available for pre-order on the Toys"R"Us Canada website, toysrus.ca, for $29.99 plus applicable taxes – and will be available for in-store purchase as of July 28. -

The South Korean Pop Stars Are Inspiring Fans Around the World to Support Good Causes

APRIL 2020 ● ARTS AND CULTURE ● VOL. 10 ● NO. 22 EDITION 2 THE BTS EFFECT The South Korean pop stars are inspiring fans around the world to support good causes. timeforkids.com ARTS Jailynne Garcia, 10, loves BTS. They of the charts. are a music group from South Korea. Fans like Jailynne are members “I like how funny they are,” Jailynne of the BTS ARMY. BTS are glad their told TIME for Kids. “I like that they’re fans feel connected to them. “That good dancers and singers. And I like was our goal, to create this empathy that they help people.” that people can relate to,” Suga said. BTS has seven members. They are He was interviewed by TIME in 2018. J-Hope, Jimin, Jin, Jung Kook, RM, Suga, and V. Together, they sing, Pay It Forward dance, and perform. Their songs BTS give back to others. They work are mostly in Korean. But they have with the United Nations Children’s Fund become international superstars. Their (UNICEF) on a big charity project. videos have been viewed billions of The group has raised MARK GARTEN—UNICEF times. Their albums have hit the top more than $2 million for BTS appear with UNICEF’s Lilly Singh (center left) and Henrietta H. Fore. COVER: SARA JAYE WEISS—SHUTTERSTOCK 2 Time for Kids April 2020 BTS perform live in New York City’s Times Square on New Year’s Eve 2019. UNICEF. This money helps protect children and teens. Jailynne and her mom are inspired by BTS. They joined a BTS fan group called One in an ARMY (OIAA). -

Gruda Mpp Me Assis.Pdf

MATEUS PRANZETTI PAUL GRUDA O DISCURSO POLITICAMENTE INCORRETO E DO ESCRACHO EM SOUTH PARK ASSIS 2011 MATEUS PRANZETTI PAUL GRUDA O DISCURSO POLITICAMENTE INCORRETO E DO ESCRACHO EM SOUTH PARK Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – UNESP – Universidade Estadual Paulista para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Psicologia (Área de Conhecimento: Psicologia e Sociedade) Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Sterza Justo Trabalho financiado pela CAPES ASSIS 2011 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) Biblioteca da F.C.L. – Assis – UNESP Gruda, Mateus Pranzetti Paul G885d O discurso politicamente incorreto e do escracho em South Park / Mateus Pranzetti Paul Gruda. Assis, 2011 127 f. : il. Dissertação de Mestrado – Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – Universidade Estadual Paulista Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Sterza Justo. 1. Humor, sátira, etc. 2. Desenho animado. 3. Psicologia social. I. Título. CDD 158.2 741.58 MATEUS PRANZETTI PAUL GRUDA O DISCURSO POLITICAMENTE INCORRETO E DO ESCRACHO EM “SOUTH PARK” Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – UNESP – Universidade Estadual Paulista para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Psicologia (Área de Conhecimento: Psicologia e Sociedade) Data da aprovação: 16/06/2011 COMISSÃO EXAMINADORA Presidente: PROF. DR. JOSÉ STERZA JUSTO – UNESP/Assis Membros: PROF. DR. RAFAEL SIQUEIRA DE GUIMARÃES – UNICENTRO/ Irati PROF. DR. NELSON PEDRO DA SILVA – UNESP/Assis GRUDA, M. P. P. O discurso do humor politicamente incorreto e do escracho em South Park.