Bruce Springsteen, Judicial Independence, and the Rule of Law Charles G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 the Human the JOURNAL of POETRY, Touch PROSE and VISUAL ART

VOLUME 10 2017 The Human THE JOURNAL OF POETRY, Touch PROSE AND VISUAL ART UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO ANSCHUTZ MEDICAL CAMPUS THE HUMAN TOUCH Volume 10 2017 GRAPHIC DESIGN EDITORS IN CHIEF Scott Allison Laura Kahn [email protected] Michael Berger ScottAllison.org James Yarovoy PRINTING EDITORIAL BOARD Bill Daley Amanda Glickman Citizen Printing, Fort Collins Carolyn Ho 970.545.0699 Diana Ir [email protected] Meha Semwal Shayer Chowdhury Nicholas Arlas This journal and all of its contents with no exceptions are covered Anjali Durandhar under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Nick Arlas Derivative Works 3.0 License. To view a summary of this license, please see SUPERVISING EDITORS http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/. Therese Jones To review the license in full, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/legalcode. Fair use and other rights are not affected by this license. To learn more about this and other Creative Commons licenses, please see http://creativecommons.org/about/licenses/meet-the-licenses. To honor the creative expression of the journal’s contributors, the unique and deliberate formats of their work have been preserved. © All Authors/Artists Hold Their Own Copyright CONTENTS CONTENTS PREFACE Regarding Henry Tess Jones .......................................................10 Relative Inadequacy Bonnie Stanard .........................................................61 Lines in Elegy (For Henry Claman) Bruce Ducker ...........................................12 -

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space With

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space with Flashbacks and Flash-forwards in the Series "Lost" Promotor: Auteur: Prof. Dr. S. Slembrouck Olga Berendeeva Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde Afstudeerrichting: Master Engels Academiejaar 2008-2009 2e examenperiode For My Parents Who are so far But always so close to me Мои родителям, Которые так далеко, Но всегда рядом ii Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank Professor Dr. Stefaan Slembrouck for his interest in my work. I am grateful for all the encouragement, help and ideas he gave me throughout the writing. He was the one who helped me to figure out the subject of my work which I am especially thankful for as it has been such a pleasure working on it! Secondly, I want to thank my boyfriend Patrick who shared enthusiasm for my subject, inspired me, and always encouraged me to keep up even when my mood was down. Also my friend Sarah who gave me a feedback on my thesis was a very big help and I am grateful. A special thank you goes to my parents who always believed in me and supported me. Thanks to all the teachers and professors who provided me with the necessary baggage of knowledge which I will now proudly carry through life. iii Foreword In my previous research paper I wrote about film discourse, thus, this time I wanted to continue with it but have something new, some kind of challenge which would interest me. After a conversation with my thesis guide, Professor Slembrouck, we decided to stick on to film discourse but to expand it. -

Easy Guitar Songbook

EASY GUITAR SONGBOOK Produced by Alfred Music Publishing Co., Inc. P.O. Box 10003 Van Nuys, CA 91410-0003 alfred.com Printed in USA. No part of this book shall be reproduced, arranged, adapted, recorded, publicly performed, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without written permission from the publisher. In order to comply with copyright laws, please apply for such written permission and/or license by contacting the publisher at alfred.com/permissions. ISBN-10: 0-7390-9399-1 ISBN-13: 978-0-7390-9399-3 Photos: Danny Clinch CONTENTS Title Release Page 4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy) . The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle . .8 Atlantic City . Nebraska . .12 Badlands . Darkness on the Edge of Town . .3 Better Days . Lucky Town . .16 Blinded by the Light . Greetings from Asbury Park, N .J . .19 Born in the U .S .A . Born in the U .S .A . .24 Born to Run . Born to Run . .26 Brilliant Disguise . Tunnel of Love . .32 Dancing in the Dark . Born in the U .S .A . .35 Glory Days . Born in the U .S .A . .64 Human Touch . Human Touch . .38 Hungry Heart . The River . .44 Lucky Town . Lucky Town . .46 My City of Ruins . The Rising . .50 My Hometown . Born in the U .S .A . .53 Pink Cadillac . B-side of “Dancing in the Dark” single . .56 Prove It All Night . Darkness on the Edge of Town . .60 The Rising . The Rising . .75 The River . The River . .78 Secret Garden . Greatest Hits . .67 Streets of Philadelphia . Philadelphia soundtrack . .70 Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out . -

Born to Run? 3

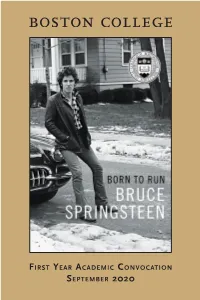

First Year academic convocation september 2020 Table of ConTenTs I. Why Read a Book? 2 II. Why Read Born to Run? 3 III. A Way to Approach the Text 5 IV. The Examen 13 V. Continuing the Conversation 16 1 Why Read a book? We can learn what is in any book on Amazon, hear what others think on Facebook, listen to a podcast if we want to learn from cutting-edge thinkers. So why sit with a thick paper tome when it’s far easier to get our information and entertainment in other forms? One answer is precisely because it is easier, and noisier, to learn and be entertained via digital and truncated means. Technology keeps us connected, linked, always visible, always able to see and be seen. Sometimes this connection, this being linked, on, and seen is valuable, worthwhile and even politically efficacious. Sometimes. But if all we ever do is check status updates, skim articles, and read summaries of other peoples’ ideas while listening to music and texting our friends, something valuable gets lost. That something goes by many names: concentration, solitude, space for reflection, intimacy, and authenticity. Reading a book, we hope you’ll learn at Boston College if you don’t already know and believe already, brings with it unique form of pleasure and thinking. Reading can take us out of the smallness of our own perception, our own little lives, the limited boundaries of what we have experienced. We can glimpse into the perspectives and even empathize with people whose lives are vastly different than our own. -

Runaway American Dream, Hope and Disillusion in the Early Work

Runaway American Dream HOPE AND DISILLUSION IN THE EARLY WORK OF BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN Two young Mexican immigrants who risk their lives trying to cross the border; thousands of factory workers losing their jobs when the Ohio steel industry collapsed; a Vietnam veteran who returns to his hometown, only to discover that he has none anymore; and young lovers learning the hard way that romance is a luxury they cannot afford. All of these people have two things in common. First, they are all disappointed that, for them, the American dream has failed. Rather, it has become a bitter nightmare from which there is no waking up. Secondly, their stories have all been documented by the same artist – a poet of the poor as it were – from New Jersey. Over the span of his 43-year career, Bruce Springsteen has captured the very essence of what it means to dream, fight and fail in America. That journey, from dreaming of success to accepting one’s sour destiny, will be the main subject of this paper. While the majority of themes have remained present in Springsteen’s work up until today, the way in which they have been treated has varied dramatically in the course of those more than forty years. It is this evolution that I will demonstrate in the following chapters. But before looking at something as extensive as a life-long career, one should first try to create some order in the large bulk of material. Many critics have tried to categorize Springsteen’s work in numerous ‘phases’. Some of them have reasonable arguments, but most of them made the mistake of creating strict chronological boundaries between relatively short periods of time1, unfortunately failing to see the numerous connections between chronologically remote works2 and the continuity that Springsteen himself has pointed out repeatedly. -

View Song List

Piano Bar Song List 1 100 Years - Five For Fighting 2 1999 - Prince 3 3am - Matchbox 20 4 500 Miles - The Proclaimers 5 59th Street Bridge Song (Feelin' Groovy) - Simon & Garfunkel 6 867-5309 (Jenny) - Tommy Tutone 7 A Groovy Kind Of Love - Phil Collins 8 A Whiter Shade Of Pale - Procol Harum 9 Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) - Nine Days 10 Africa - Toto 11 Afterglow - Genesis 12 Against All Odds - Phil Collins 13 Ain't That A Shame - Fats Domino 14 Ain't Too Proud To Beg - The Temptations 15 All About That Bass - Meghan Trainor 16 All Apologies - Nirvana 17 All For You - Sister Hazel 18 All I Need Is A Miracle - Mike & The Mechanics 19 All I Want - Toad The Wet Sprocket 20 All Of Me - John Legend 21 All Shook Up - Elvis Presley 22 All Star - Smash Mouth 23 All Summer Long - Kid Rock 24 All The Small Things - Blink 182 25 Allentown - Billy Joel 26 Already Gone - Eagles 27 Always Something There To Remind Me - Naked Eyes 28 America - Neil Diamond 29 American Pie - Don McLean 30 Amie - Pure Prairie League 31 Angel Eyes - Jeff Healey Band 32 Another Brick In The Wall - Pink Floyd 33 Another Day In Paradise - Phil Collins 34 Another Saturday Night - Sam Cooke 35 Ants Marching - Dave Matthews Band 36 Any Way You Want It - Journey 37 Are You Gonna Be My Girl? - Jet 38 At Last - Etta James 39 At The Hop - Danny & The Juniors 40 At This Moment - Billy Vera & The Beaters 41 Authority Song - John Mellencamp 42 Baba O'Riley - The Who 43 Back In The High Life - Steve Winwood 44 Back In The U.S.S.R. -

Meanings and Measures Taken in Concert Observation of Bruce Springsteen, September 28, 1992, Los Angeles

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1996 Meanings and measures taken in concert observation of Bruce Springsteen, September 28, 1992, Los Angeles Thomas J Rodak University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Rodak, Thomas J, "Meanings and measures taken in concert observation of Bruce Springsteen, September 28, 1992, Los Angeles" (1996). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 3215. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/bgs9-fpv1 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality' illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. -

The River Bruce

1 SONGS: NIVEL AVANZADO: THE RIVER: BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN ESCUELA CENTRO DE AUTOAPRENDIZAJE OFICIAL IDIOMA: INGLÉS DE PRÁCTICA: COMPRENSIÓN ORAL IDIOMAS NIVEL: NIVEL AVANZADO OVIEDO MATERIAL: CINTA-CD / CUESTIONARIO / SOLUCIONES TEMA: STORY SONG, WOULD FOR PAST HABITS "The Boss" hit the music industry with the release of his first album Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J., in 1973. His first albums received critical claim with comparisons to Bob Dylan, but did not sell well with the fans. Bruce Springsteen's career had begun. Springsteen was born in Freehold, New Jersey, on September 23, 1949. He grew up in a "normal middle class family" and first started playing around with the guitar in High School. After graduating from High School he moved to New York to try and break into the Folk Music scene. After getting nowhere on this front he returned to, be it reluctantly, to Asbury Park, N.J. and hooked up with a number of bands. With brief stints with such bands as Rogues and Dr. Zoom and the Sonic Boom, Springsteen found himself a place with the E-Street Band, and with them he remained until 1989. Though, this wouldn't be the last time they would play together. The 1973 albums marked the beginning of Springsteen's career and since then, "The Boss" has sold tens of millions of albums and won over legions of loyal fans worldwide in his 30 plus years as a "rock and roll legend". His break came after a tour with the band Chicago. Springsteen captivated the audiences in these live shows, and seeing an opportunity, the singer-songwriter came up with what is called his breakthrough effort Born to Run in 1974. -

Jon Anderson Dalai Angolul, Magyarul Jon Anderson`S Songs in English and in Hungarian

Szerény kísérlet az elveszett harmónia megtalálására Modest attempt to find the lost harmony Jon Anderson dalai angolul, magyarul Jon Anderson`s songs in English and in Hungarian 1 Jon Anderson 2 Table of Contents Tartalomjegyzék So Far Away, So Clear - Oly messzi, oly tiszta (1975)______________________________ 4 Olias of Sunhillow (1976)____________________________________________________ 5 Short Stories - Novellák (1980) ______________________________________________ 12 Song of Seven – A hét dala (1980) ____________________________________________ 20 The Friends Of Mr. Cairo – Kairo úr barátai (1981) _____________________________ 32 Animation – Mozgatás (1982) _______________________________________________ 33 ¤ 3ULYDW &ROOHFWLR ¡£¢ 0DJiQJ\&MWHPpQ __________________________________ 34 Three Ships - Három hajó (1985) ____________________________________________ 41 In The City Of Angels - Az angyalok városában (1988) ___________________________ 53 "LOVED BY THE SUN"(A NAP SZERETTE) ____________________________________ 73 Requiem For The Americas - Rekviem az amerikaiakért (1989) ____________________ 74 Page Of Life - Az élet oldala (1991) ___________________________________________ 78 Close To The Hype – Közel a feldobott állapothoz (1992)__________________________ 81 Dream - Álom (1992) ______________________________________________________ 82 Change We Must - Meg kell változnunk (1994) _________________________________ 87 Deseo (1994) ____________________________________________________________ 105 ¦ §©¨ ¦ ¦ ,WC¥ $ERX 7LP (OM| D LG -

Touch the Human

VOLUME 12 2019 The Human THE JOURNAL OF POETRY, Touch PROSE AND VISUAL ART UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO | ANSCHUTZ MEDICAL CAMPUS THE JOURNAL OF Poetry, Prose, & Visual Art University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus FRONT COVER ARTWORK The Tree of Love ARTURO GARCIA BACK COVER ARTWORK Lighthouse Staircase AREK WIKTOR GRAPHIC DESIGN Scott Allison [email protected] ScottAllison.org PRINTING Bill Daley Citizen Printing, Fort Collins 970.545.0699 [email protected] This journal and all of its contents with no exceptions are covered under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. To view a summary of this license, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/. To review the license in full, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/legalcode. Fair use and other rights are not affected by this license. To learn more about this and other Creative Commons licenses, please see http://creativecommons.org/about/licenses/meet-the-licenses. To honor the creative expression of the journal’s contributors, the unique and deliberate formats of their work have been preserved. © All Authors/Artists Hold Their Own Copyright THE HUMAN TOUCH Volume 12 2019 EDITORS IN CHIEF Carolyn Ho Diana Ir Priya Krishnan EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS Elsa Alaswad Nicholas Arlas Riannon Atwater Raisa Bailon James Carter Shayer Chowdhury Samantha Conner Tom Henry David Amelia Davis Anjali Dhurandhar Thanhnga Doan Allison Dubner Nina Elder Kirk Fetters Lynn Fox Amanda Glickman George Ho Sophia Hu Carolyn Jones Vladka Kovar Cecille Lamorena Christine Lee Daniel Maher Barry Manembu Zoe Owrutsky Jenna Pratt Meha Semwal Kelly Stanek Helena Winston SUPERVISING EDITOR Therese Jones CONTENTS PREFACE ..................................................................................................7 I Finished Reading a Book Then Walked Down the Street Fredrick R. -

The Backstreets Liner Notes

the backstreets liner notes BY ERIK FLANNIGAN AND CHRISTOPHER PHILLIPS eyond his insightful introductory note, Bruce Springsteen elected not to annotate the 66 songs 5. Bishop Danced RECORDING LOCATION: Max’s Kansas City, New included on Tracks. However, with the release York, NY of the box set, he did give an unprecedented RECORDING DATE: Listed as February 19, 1973, but Bnumber of interviews to publications like Billboard and MOJO there is some confusion about this date. Most assign the which revealed fascinating background details about these performance to August 30, 1972, the date given by the King songs, how he chose them, and why they were left off of Biscuit Flower Hour broadcast (see below), while a bootleg the albums in the first place. Over the last 19 years that this release of the complete Max’s set, including “Bishop Danced,” magazine has been published, the editors of Backstreets dated the show as March 7, 1973. Based on the known tour have attempted to catalog Springsteen’s recording and per- chronology and on comments Bruce made during the show, formance history from a fan’s perspective, albeit at times an the date of this performance is most likely January 31, 1973. obsessive one. This booklet takes a comprehensive look at HISTORY: One of two live cuts on Tracks, “Bishop Danced” all 66 songs on Tracks by presenting some of Springsteen’s was also aired on the inaugural King Biscuit Flower Hour and own comments about the material in context with each track’s reprised in the pre-show special to the 1988 Tunnel of Love researched history (correcting a few Tracks typos along the radio broadcast from Stockholm. -

Read Book Eat and Run: My Unlikely Journey to Ultramarathon

EAT AND RUN: MY UNLIKELY JOURNEY TO ULTRAMARATHON GREATNESS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Scott Jurek,Steve Friedman | 272 pages | 26 Aug 2013 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781408833407 | English | London, United Kingdom Eat and Run: My Unlikely Journey to Ultramarathon Greatness PDF Book Lists with This Book. I thought I had run more difficult courses. Until recently he held the American hour record and he was one of the elite runners profiled in the runaway bestseller Born to Run. I was hungry and I had a race coming up, so I ate them. I mean, you don't see Kenyan running champion Samuel Wanjiru following a special diet. Interesting book and an okay read. And it was -- but the writing was not. In terms of knowledge, there wasn't an incredibly amount of things I really gathered from it, despite me having a good time reading about the races Jurek took part in. Definitely a must read for any runner, understanding just how much Scott overcame is super inspirational. I had worn specially designed heat-reflecting pants and shirt. The result is this perceptive, He squatted, folded himself until our faces were inches apart. This was supposed to be my time. Or was I a fraud? Running is what I love. Books by Scott Jurek. It's just weird to mold yourself as this ultimate competitor and then apparently not compete a lot if you aren't going to win. The has a bit of a biography feel to it. Motivating book. You can try and make me feel sorry for you, but you had time to run so you had time for yourself.