2018 Elk Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0 5 10 15 20 Miles Μ and Statewide Resources Office

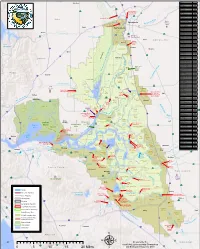

Woodland RD Name RD Number Atlas Tract 2126 5 !"#$ Bacon Island 2028 !"#$80 Bethel Island BIMID Bishop Tract 2042 16 ·|}þ Bixler Tract 2121 Lovdal Boggs Tract 0404 ·|}þ113 District Sacramento River at I Street Bridge Bouldin Island 0756 80 Gaging Station )*+,- Brack Tract 2033 Bradford Island 2059 ·|}þ160 Brannan-Andrus BALMD Lovdal 50 Byron Tract 0800 Sacramento Weir District ¤£ r Cache Haas Area 2098 Y o l o ive Canal Ranch 2086 R Mather Can-Can/Greenhead 2139 Sacramento ican mer Air Force Chadbourne 2034 A Base Coney Island 2117 Port of Dead Horse Island 2111 Sacramento ¤£50 Davis !"#$80 Denverton Slough 2134 West Sacramento Drexler Tract Drexler Dutch Slough 2137 West Egbert Tract 0536 Winters Sacramento Ehrheardt Club 0813 Putah Creek ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Empire Tract 2029 ·|}þ84 Fabian Tract 0773 Sacramento Fay Island 2113 ·|}þ128 South Fork Putah Creek Executive Airport Frost Lake 2129 haven s Lake Green d n Glanville 1002 a l r Florin e h Glide District 0765 t S a c r a m e n t o e N Glide EBMUD Grand Island 0003 District Pocket Freeport Grizzly West 2136 Lake Intake Hastings Tract 2060 l Holland Tract 2025 Berryessa e n Holt Station 2116 n Freeport 505 h Honker Bay 2130 %&'( a g strict Elk Grove u Lisbon Di Hotchkiss Tract 0799 h lo S C Jersey Island 0830 Babe l Dixon p s i Kasson District 2085 s h a King Island 2044 S p Libby Mcneil 0369 y r !"#$5 ·|}þ99 B e !"#$80 t Liberty Island 2093 o l a Lisbon District 0307 o Clarksburg Y W l a Little Egbert Tract 2084 S o l a n o n p a r C Little Holland Tract 2120 e in e a e M Little Mandeville -

Desilva Island

SUISUN BAY 139 SUISUN BAY 140 SUISUN BAY SUISUN BAY Located immediately downstream of the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, Suisun Bay is the largest contiguous wetland area in the San Francisco Bay region. Suisun Bay is a dynamic, transitional zone between the freshwater input of the Central Valley rivers and the tidal influence of the upper San Francisco Estuary. This area supports a substantial number of nesting herons and egrets, including three of the largest colonies in the region. Although suburban development is rampant along the nearby Interstate 80 corridor to the north, most of the Suisun Bay area is protected from heavy development by the California Department of Fish and Game and a number of private duck clubs. Black- Active Great crowned or year Site Blue Great Snowy Night- Cattle last # Colony Site Heron Egret Egret Heron Egret County active Page 501 Bohannon Solano Active 142 502 Campbell Ranch Solano Active 143 503 Cordelia Road Solano 1998 145 504 Gold Hill Solano Active 146 505 Green Valley Road Solano Active 148 506 Hidden Cove Solano Active 149 507 Joice Island Solano 1994 150 508 Joice Island Annex Solano Active 151 509 Sherman Lake Sacramento Active 152 510 Simmons Island Solano 1994 153 511 Spoonbill Solano Active 154 512 Tree Slough Solano Active 155 513 Volanti Solano Active 156 514 Wheeler Island Solano Active 157 SUISUN BAY 141 142 SUISUN BAY Bohannon Great Blue Herons and Great Egrets nest in a grove of eucalyptus trees on a levee in Cross Slough, about 1.8 km east of Beldons Landing. -

Suisun Marsh Protection Plan Map (PDF)

Proposed County Parks (Hill Slough, Fairfield Beldon’s Landing) Develop passive recreation facilities compatible with Marsh protection (e.g. fishing, picnicking, hiking, nature study.) Boat launching ramp may be constructed Suis nu at Beldon’s Landing. City Suisun Marsh 8 0 etaterstnI 80 a Protection Plan Map flHighway 12 San Francisco Bay Conservation (6) b .J ' and Development Commission I Denverton (7) I December 1976 ) I ~4 Slough Thomasson Shiloh Primary Management Area danyor, Potrero Hills ':__. .---) ... .. ... ~ . _,,. - (8) Secondary Management Area ~ ,. .,,,, Denverton ,,a !\.:r ~ Water-Related Industry Reserve Area c Beldon’s BRADMOOR ISLAND Slough (5) Landing t +{larl!✓' Road Boundary of Wildlife Areas and (9) Ecological Reserves Little I Honker (1) Grizzly Island Unit (9) Bay (2) Crescent Unit (4) Montezuma Slough (3) Island Slough Unit JOICE ISLAND (3) r (4) Joice Island Unit (5) Rush Ranch National Estuarine (10) Ecological Reserve Kirby Hill (6) Hill Slough Wildlife Area Suisun (7) Peytonia Slough Ecological Reserve (8) Grey Goose Unit GRIZZLY ISLAND (2) GRIZZLY ISLAND (9) Gold Hills Unit (10) Garibaldi Unit (11) West Family Unit (12) Goodyear Slough Unit Benicia Area Recommended for Aquisition a. Lawler Property I (11) Hills b. Bryan Property . ~-/--,~ c. Smith Property ,,-:. ...__.. ,, \ 1 Collinsville: Reserve seasonal marshes and Benicia Hills lowland grasslands for their Amended 2011 Grizzly Bay intrinsic value to marsh wildlife and Steep slopes with high landslide and soil to act as the buffer between the erosion potentials. Active fault location. Land (1) Marsh and any future water-related Collinsville Road use practices should be controlled to prevent uses to the east. -

550. Regulations for General Public Use Activities on All State Wildlife Areas Listed

550. Regulations for General Public Use Activities on All State Wildlife Areas Listed Below. (a) State Wildlife Areas: (1) Antelope Valley Wildlife Area (Sierra County) (Type C); (2) Ash Creek Wildlife Area (Lassen and Modoc counties) (Type B); (3) Bass Hill Wildlife Area (Lassen County), including the Egan Management Unit (Type C); (4) Battle Creek Wildlife Area (Shasta and Tehama counties); (5) Big Lagoon Wildlife Area (Humboldt County) (Type C); (6) Big Sandy Wildlife Area (Monterey and San Luis Obispo counties) (Type C); (7) Biscar Wildlife Area (Lassen County) (Type C); (8) Buttermilk Country Wildlife Area (Inyo County) (Type C); (9) Butte Valley Wildlife Area (Siskiyou County) (Type B); (10) Cache Creek Wildlife Area (Colusa and Lake counties), including the Destanella Flat and Harley Gulch management units (Type C); (11) Camp Cady Wildlife Area (San Bernadino County) (Type C); (12) Cantara/Ney Springs Wildlife Area (Siskiyou County) (Type C); (13) Cedar Roughs Wildlife Area (Napa County) (Type C); (14) Cinder Flats Wildlife Area (Shasta County) (Type C); (15) Collins Eddy Wildlife Area (Sutter and Yolo counties) (Type C); (16) Colusa Bypass Wildlife Area (Colusa County) (Type C); (17) Coon Hollow Wildlife Area (Butte County) (Type C); (18) Cottonwood Creek Wildlife Area (Merced County), including the Upper Cottonwood and Lower Cottonwood management units (Type C); (19) Crescent City Marsh Wildlife Area (Del Norte County); (20) Crocker Meadow Wildlife Area (Plumas County) (Type C); (21) Daugherty Hill Wildlife Area (Yuba County) -

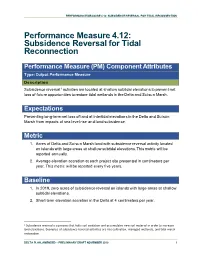

Subsidence Reversal for Tidal Reconnection

PERFORMANCE MEASURE 4.12: SUBSIDENCE REVERSAL FOR TIDAL RECONNECTION Performance Measure 4.12: Subsidence Reversal for Tidal Reconnection Performance Measure (PM) Component Attributes Type: Output Performance Measure Description 1 Subsidence reversal 0F activities are located at shallow subtidal elevations to prevent net loss of future opportunities to restore tidal wetlands in the Delta and Suisun Marsh. Expectations Preventing long-term net loss of land at intertidal elevations in the Delta and Suisun Marsh from impacts of sea level rise and land subsidence. Metric 1. Acres of Delta and Suisun Marsh land with subsidence reversal activity located on islands with large areas at shallow subtidal elevations. This metric will be reported annually. 2. Average elevation accretion at each project site presented in centimeters per year. This metric will be reported every five years. Baseline 1. In 2019, zero acres of subsidence reversal on islands with large areas at shallow subtidal elevations. 2. Short-term elevation accretion in the Delta at 4 centimeters per year. 1 Subsidence reversal is a process that halts soil oxidation and accumulates new soil material in order to increase land elevations. Examples of subsidence reversal activities are rice cultivation, managed wetlands, and tidal marsh restoration. DELTA PLAN, AMENDED – PRELIMINARY DRAFT NOVEMBER 2019 1 PERFORMANCE MEASURE 4.12: SUBSIDENCE REVERSAL FOR TIDAL RECONNECTION Target 1. By 2030, 3,500 acres in the Delta and 3,000 acres in Suisun Marsh with subsidence reversal activities on islands, with at least 50 percent of the area or with at least 1,235 acres at shallow subtidal elevations. 2. An average elevation accretion of subsidence reversal is at least 4 centimeters per year up to 2050. -

East Bay Industrial Opportunity 2380-2388 Williams Street + 1717 Doolittle Drive

OFFERING MEMORANDUM SAN FRANCISCO BAY BRIDGE PORT OF DOWNTOWN OAKLAND OAKLAND ALAMEDA OAKLAND COLISEUM & ARENA OAKLAND INT’L AIRPORT DOOLITTLE DRIVE SUBJECT PROPERTY WILLIAMS ST EAST BAY INDUSTRIAL OPPORTUNITY 2380-2388 WILLIAMS STREET + 1717 DOOLITTLE DRIVE 585,517 SF Class A, Industrial Park // 100% Leased to High Quality Logistic/Manufacturing Tenants Strategic Last Mile Location – 1.5 Miles to Oakland Airport // Within a 30 Mile Radius of 6.0 Million Residents A CBRE NATIONAL PARTNERS INDUSTRIAL INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY WAYFAIR4 EXECUTIVE TRUCK DOCK SUMMARY PACKAGES – 2388 WILLIAMS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY THE OFFERING CBRE is pleased to offer for sale an institutionally developed-redeveloped, 100% leased multi-tenant industri- al property in the East Bay Industrial market of Northern California. The 2017-constructed 163,979 SF Class A 32’ Clear ESFR warehouse at 2380-2388 Williams is complemented by the 421,538 SF manufacturing & warehouse building at 1717 Doolittle. The property is 100% leased to National and Global credit logistics tenants, and is located in one of the most robust markets in the U.S. with a less than 2% vacancy rate. Situated 1.5 miles south of Oakland International Airport and within 10 miles of the Port of Oakland (the 4th largest U.S. shipping port), this project attracts companies seeking an infill logistics location that wish to take DOOLITTLE DRIVE advantage of the highly educated technology and manufacturing labor pool. 1717 DOOLITTLE DRIVE 2050 WILLIAMS STREET 2250 WILLIAMS STREET WILLIAMS ST 2380-2388 WILLIAMS STREET 1717 DOOLITTLE DRIVE PROPERTY TOTAL SAN LEANDRO, CA SAN LEANDRO, CA 2350 WILLIAMS STREET SQUARE FOOTAGE ±163,979 SF ±421,538 SF 585,517 SF OCCUPANCY 100% 100% 100% YEAR BUILT 2017 1955, Ren. -

Field Assessment of Avian Mercury Exposure in the Bay-Delta Ecosystem

Assessment of Ecological and Human Health Impacts of Mercury in the Bay-Delta Watershed CALFED Bay-Delta Mercury Project Subtask 3B: Field assessment of avian mercury exposure in the Bay-Delta ecosystem. Draft Final Report Submitted to Mark Stephenson Director Marine Pollution Studies labs Department of Fish and Game Moss Landing Marine Labs 7544 Sandholt Rd. Moss Landing, Ca 95039 Submitted by: Dr. Steven Schwarzbach USGS Biological Research Division Western Ecological Research Center 7801 Folsom Blvd. Sacramento California 95826 and Terry Adelsbach US Fish and Wildlife Service Sacramento Fish and Wildlife Office Environmental Contaminants Division 2800 Cottage Way, Sacramento Ca. 95825 1 BACKGROUND The Bay/Delta watershed has a legacy of mercury contamination resulting from mercury mining in the Coast Range and the use of this mercury in the amalgamation method for extraction of gold from stream sediments and placer deposits in the Sierra Nevada. Because mercury, and methylmercury in particular, strongly bioaccumulate in aquatic foodwebs there has been a reasonable speculation that widespread mercury contamination of the bay/delta from historic sources in the watershed could be posing a health threat to piscivorous wildlife. As a result this systematic survey of mercury exposure in aquatic birds was conducted in both San Francisco Bay and the Sacramento/San Joaquin Delta. The Delta component of the survey was subtask 3b of the CalFed mercury project. The San Francisco Bay component of the project was conducted at the behest of the California Regional Water Quality Control Board, Region 2, San Francisco Bay. Results of both projects are reported on here because of overlap in methods and species sampled, the interconnectedness of the Bay/Delta estuary and the need to address avian wildlife risk of mercury in the region as a whole. -

High Resolution Measurement of Levee Subsidence Related to Energy Infrastructure in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

HIGH RESOLUTION MEASUREMENT OF LEVEE SUBSIDENCE RELATED TO ENERGY INFRASTRUCTURE IN THE SACRAMENTO-SAN JOAQUIN DELTA A Report for: California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment Prepared By: Benjamin A. Brooks1 , Jennifer Telling2 , Todd Ericksen1 ,Craig L. Glennie2 , Noah Knowles3, Dan Cayan4 , Darren Hauser2 , Adam LeWinter5 1 Earthquake Science Center 2National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping (NCALM) 3California Water Resources Center 4CASPO 5U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as the result of work sponsored by the California Energy Commission. It does not necessarily represent the views of the Energy Commission, its employees or the State of California. The Energy Commission, the State of California, its employees, contractors and subcontractors make no warrant, express or implied, and assume no legal liability for the information in this report; nor does any party represent that the uses of this information will not infringe upon privately owned rights. This report has not been approved or disapproved by the California Energy Commission nor has the California Energy Commission passed upon the accuracy or adequacy of the information in this report. Edmund G. Brown Jr., Governor August 2018 CCCA4-CEC-2018-003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank Luke Blair and Fernando Martinez for their help with preliminary processing of the Airborne LIDAR data. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Support for this research was provided by the California Energy Commission Agreement Number 500-14-001. i PREFACE California’s Climate Change Assessments provide a scientific foundation for understanding climate-related vulnerability at the local scale and informing resilience actions. -

Conceptual Model for Managed Wetlands in Suisun Marsh

Initial Draft Conceptual Model for Managed Wetlands in Suisun Marsh Compiled by Department of Fish and Game (DFG) and Suisun Resource Conservation District (SRCD) staff Contributors: Laureen Barthman – Thompson (DFG) Kristin Bruce (SRCD) Sarah Estrella (DFG) Paul Garrison III (DFG) Craig Haffner (SRCD) Julie Niceswanger (DFG) Gina Van Klompenburg (DFG) Bruce Wickland (SRCD) With input from: Dennis Becker Laurie Briden Cecilia Brown Steve Chappell Steve Culberson Cassandra Enos Chris Enright Bellory Fong Terri Gaines Jasper Lament Conrad Jones Victor Pacheco Facilitated by: Zachary Hymanson Stuart Siegel 1 Table of Contents 1.0 MANAGED WETLAND MANAGEMENT GOALS AND ASSUMPTIONS .................................. 5 2.0 CURRENT CONDITIONS .................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 PHYSICAL .......................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1.1 Applied water salinity .................................................................................................................. 6 2.1.2 Slough water salinity / Marsh-wide salinity gradient (DWR 2001) ............................................. 7 2.1.3 Soils .............................................................................................................................................. 7 2.1.4 Water year ................................................................................................................................... -

1.3 Warren Act Contract

EXECUTION OF TWO WARREN ACT CONTRACTS TO WESTLANDS WATER DISTRICT AND WESTLANDS WATER DISTRICT DISTRIBUTION DISTRICT 1 TO FACILITATE A NON-CVP WATER TRANSFER FROM PLACER COUNTY WATER AGENCY CENTRAL VALLEY PROJECT, CALIFORNIA MID PACIFIC REGION SOUTH-CENTRAL CALIFORNIA AREA OFFICE ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT #EA-08-91 U.S. Department of the Interior October 2008 Bureau of Reclamation Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction.....................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 Statement of Purpose and Need ..............................................................................1-2 1.2 Purpose of this Environmental Assessment............................................................1-3 1.3 Warren Act Contract...............................................................................................1-3 1.4 Project Agencies and Related Facilities..................................................................1-3 1.4.1 Placer County Water Agency ....................................................................1-3 1.4.2 Westlands Water District and Westlands Water District Distribution District No. 1 .........................................................................1-5 1.4.3 Central Valley Project................................................................................1-5 2.0 Description of Proposed Action and Alternatives........................................................2-1 2.1 No Action Alternative.............................................................................................2-1 -

Land of the West Wind

Land of the West Wind Volume 17 Issue 4 December 2017 Grizzly Island Wildlife Area Waterfowl Harvest Update By: Orlando Rocha, CDFW Opening weekend for our hunters was outstanding, we held our own against some of the larger An Abundance of Scientific Projects in Suisun Marsh Valley hunt areas and our aver- ages for opening weekend were A large number of exciting research studies are currently ongoing in up considerably; 4.60 Saturday Suisun Marsh. Studies by UC Davis, USGS, California Department of and 1.97 on Sunday. The average Fish and Wildlife, Department of Water Resources and many other was up from the previous year a partners are yielding impressive results, and are likely to reveal much 1.66 in 2016/17 to a 4.60 this more information in the next few years. There was by no means year; we actually had less hunters enough room to include all the information that may affect those opening Saturday but shot more who enjoy the bounty of waterfowl in the marsh, but a few of those birds than in recent history. We studies are described here. Also, some of the researchers are looking for club participants and may be in contact for your help. have not seen numbers like this since before the drought period Wintering Ecology of Diving Ducks in Suisun Marsh and the last time we had opening By: Susan E. W. De La Cruz, PhD day averages over a 4-bird aver- USGS Research Wildlife Biologist age was back in 2006/2007. A quick overview shows us that The USGS San Francisco Bay Estuary Field Station is currently evaluat- there were more mallards shot ing diving duck wintering ecology in Suisun Bay and Marsh. -

Geology of the San Francisco Bay Region, by Doris Sloan University of California Press/California Natural History Guides, 2005

Geology of the San Francisco Bay Region, by Doris Sloan University of California Press/California Natural History Guides, 2005 Abbotts Lagoon, 92 basement rocks, 49, 55–70 accretion, 31 See also Franciscan Complex; Great Valley accretionary wedges, 30 (figure), 31 Complex; Salinian Complex; specific regions actinolite, 269 and types of rock Alameda Creek, 218, 224, 225 basins Albany Hill, 231 fore-arc basins, 30 (figure), 64 Alcatraz Island, 125, 151–152, 152 (plate), 153 (plate) formed by transpression, 42–43, 42 (figure) Alcatraz Terrane, 65 (table), 104, 124 (map), 125–126, 152, landslide basins, Mount Tamalpais, 107 153 (plate), 233 sag ponds, 36 (figure), 37, 84, 167, 194, 262 (plate), Alexander Valley, 273 263 alluvial deposits See also lakes; San Francisco Bay; specific lakes and East Bay, 218, 219, 225, 231, 248 valleys North Bay, 255, 264, 283 Bay Block. See San Francisco Bay Block San Francisco Bay floor, 142, 143, 143 (figure) beach pebbles, 57, 58 (plate), 102, 271 San Francisco Bay shore, 146–147, 218, 225, 255 beach sands, 19–23, 20 (plate), 21 (figure) South Bay, 192, 205–206, 206–207 Bodega Head, 22 (plate), 266 See also geologic maps Marin Headlands, 102 Almaden Quicksilver County Park, 66, 200, 211–215 San Francisco, 22 (plate), 122–123 Almaden Reservoir, 201, 203 Bean Hollow State Beach, 60 (plate), 170 Alpine Lake, 96, 107 Bear Creek, 273 Altamont Hills, 233, 234, 234 (plate), 238–239 Berkeley, 37, 38 (plate), 230, 249 (plate) Alum Rock, 210, 211 (plate) Berkeley Hills, 219 (plate), 251 Alum Rock Block, 196–197 (map),