THE POLLUTANT PERFUME – Poison by Christian Dior, 1985

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury This One, with Gratitude, Is for DON CONGDON

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury This one, with gratitude, is for DON CONGDON. FAHRENHEIT 451: The temperature at which book-paper catches fire and burns PART I: THE HEARTH AND THE SALAMANDER IT WAS A PLEASURE TO BURN. IT was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history. With his symbolic helmet numbered 451 on his stolid head, and his eyes all orange flame with the thought of what came next, he flicked the igniter and the house jumped up in a gorging fire that burned the evening sky red and yellow and black. He strode in a swarm of fireflies. He wanted above all, like the old joke, to shove a marshmallow on a stick in the furnace, while the flapping pigeon- winged books died on the porch and lawn of the house. While the books went up in sparkling whirls and blew away on a wind turned dark with burning. Montag grinned the fierce grin of all men singed and driven back by flame. He knew that when he returned to the firehouse, he might wink at himself, a minstrel man, Does% burntcorked, in the mirror. Later, going to sleep, he would feel the fiery smile still gripped by his Montag% face muscles, in the dark. -

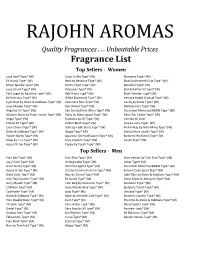

Fragrance List Print

Quality Fragrances . Unbeatable Prices Fragrance List Top Sellers - Women Love Spell Type* (W) Gucci Guilty Type* (W) Romance Type* (W) Ed Hardy Type*RAJOHN (W) Heat by Beyonce Type* (W)AROMASBlack by Kenneth Cole Type* (W) Moon Sparkle Type* (W) Jimmy Choo Type* (W) Beautiful Type* (W) Love Struck Type* (W) Pleasures Type* (W) Bombshell by VS Type* (W) Pink Sugar by Aquolina Type* (W) Reb'l Fleur Type* (W) Black Woman Type* (W) Be Delicious Type* (W) White Diamonds Type* (W) Versace Bright Crystsal Type* (W) Light Blue by Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Cashmere Mist Type* (W) Candy by Prada Type* (W) Issey Miyake Type* (W) Butt Naked Type* (W) Michael Kors Type* (W) Angel by VS Type* (W) Can Can by Paris Hilton Type* (W) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* (W) Modern Muse by Estee Lauder Type* (W) Daisy by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Miss Dior Cherie Type* (W) Angel Type* (W) Euphoria by CK Type* (W) Lick Me All Over Chanel #5 Type* (W) Amber Blush Type* (W) Viva La Juicy Type* (W) Coco Chanel Type* (W) Halle by Halle Berry Type* (W) Pink Friday by Nicki Minaj Type* (W) Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Happy Type* (W) Dot by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Flower Bomb Type* (W) Japanese Cherry Blossom Type* (W) Burberry Weekend Type* (W) Glow by J. Lo Type* (W) Juicy Couture Type* (W) Coach Type* (W) Acqua Di Gio Type* (W) Poppy by Coach Type* (W) Top Sellers - Men Polo Red Type* (M) Polo Blue Type* (M) Grey Vetiver by Tom Ford Type* (M) Jay-Z Gold Type* (M) Unforgivable Type* (M) Usher Type* (M) Gucci Guilty Type* (M) Chrome Legend Type* (M) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* -

Paco Rabanne

HERSTELLER DUFT NR PRODUKTART Aerin Amber Musk 834 PR Aventus Creed 372 P KS Bottega Veneta 819 PR Burberry The Beat 239 P Burberry London 257 P Byredo Bal D´Afrique 709 PR Cacharel Amore Amore 23 P PP PI Calvin Klein Eternity Flame 484 P Euphoria 171 PR DG Deep Euphoria 802 PR Carolina Herrera Good Girl 431 P PP 212 714 PR Cerruti Cerruti 1881 706 P Chanel Coco Mademoiselle 18 P PP PI DG BL DR KS RS No.5 21 P PI No.5 Red Limited Edition 826 PR Chance 34 P PP Chance eau Fraiche 707 PR Chance eau Tendre 322 PR Coco Noir 365 PR Gabrielle 800 PR Chloé L´Eau de Chloe 488 P Love Story 807 PR Nomade 447 P Christina Aguilera Christina Aguillera 237 P Davidoff Cool Water 419 P Dior Addict 142 PR Cherie 80 P Dune 825 PR Hypnotic Poison 173 P PI DG BL DR Jádore 10 P PP PI J´adore In Joy 806 PR Joy 445 P Midnight Poison 286 PR HERSTELLER DUFT NR PRODUKTART Dior Miss Dior Absolute Blooming 427 P Miss Dior 432 P Miss Dior 2017 801 PR Miss Dior Blooming Bouquet 810 PR Miss Dior Rose N´Roses 848 PR NEU Poison Girl 434 P DKNY Be Delicious 81 P PP PI DG BL DR Golden Delicious 443 P Dolce & Gabbana Light Blue 33 P PP PI DG BL DR The One 147 PR 3 L`Imperatrice 701 P Peony 836 PR The Only One 444 P Donna Trussardi Donna 355 PR Elisabeth Arden Green Tea 6 P Ellie Saab Le Parfum 352 PR Emporio Armani Because It´s You 817 PR Diamonds 180 P Escada Moon Sparkle 281 PR Estee Lauder Modern Muse 715 PR Ex Nihilo Fleur Narcotique 708 PR Giorgio Armani Aqua di Gio 7 P Armani Code 101 P PP Mania 177 P My Way 847 PR NEU Si 362 PR Cashmere 438 P Si Intense 804 PR Givenchy -

Passionate About Creativity

LVMH PASSIONATE ABOUT CREATIVITY Annual report 2007 passionate contents 02 . Chairman’s Message 14 . Review of operations 06. Financial Highlights 16. Wines & Spirits 08. Interview with Antonio Belloni: 24. Fashion & Leather Goods Many talents – a single success 32. Perfumes & Cosmetics 10. Corporate Governance 40. Watches & Jewelry 12. The LVMH Share 46. Selective Retailing 2007 LVMH about creativity 2007 52 . Sustainable development 54. Human resources Strengthening talents – Committing values 62. Corporate sponsorship to support culture, youth and humanitarian action 63. Protecting the environment 67 . Consolidated Financial Statements 01 Chairman’s Message Chairman’s The main strength of our Group, demonstrated by the consistency of the financial results, is without doubt LVMH’s unique portfolio of exceptional, globally recognised brands which are emblematic of the history and the world Bernard Arnault of luxury. an 02 Continue 2007 LVMH THE GROWTH OF LVMH HAS BEEN DRIVEN BY STRONG CONSUMER DEMAND FOR OUR PRODUCTS, AS MUCH IN EUROPE AND THE UNITED STATES AS IN EMERGING MARKETS. IN CHINA, RUSSIA AND INDIA, ALL MARKETS WITH STRONG CULTURAL TRADITIONS, NEW CLIENTS ARE LOOKING TO LVMH’S STAR BRANDS AS SYMBOLIC OF A LIFESTYLE TO WHICH THEY ASPIRE ENTHU- SIASTICALLY. THANKS TO ITS UNIQUE PORTFOLIO OF ICONIC BRANDS, THE TALENT OF ITS TEAMS AND THE GLOBAL REACH OF ITS BUSINESS, LVMH IS IN AN EXCELLENT POSITION TO GAIN MARKET SHARE AND TO CONTINUE ITS LEADERSHIP IN THE LUXURY GOODS MARKET IN 2008 AND BEYOND. By accentuating growth in both traditional and Louis Vuitton trunks have been sold in Australia to invest in their development. Over the years emerging markets over the course of 2007, since the end of the 19th century. -

Journal of Intellectual Property and Entertainment Law

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND ENTERTAINMENT LAW VOLUME 5 FALL 2015 NUMBER 1 LOST AND FOUND: INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY OF THE FRAGRANCE INDUSTRY; FROM TRADE SECRET TO TRADE DRESS CHARLES CRONIN* INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................257 I. THE FRAGRANCE INDUSTRY AND THE CHALLENGE OF REVERSE ENGINEERING ................................................................................................263 A. Regulation of Reverse Engineering in the United States and the European Union .....................................................................................263 B. Challenges to the Fragrance Industry’s Traditional Reliance on Trade Secrets ..........................................................................................267 C. The Impact of Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Technologies on the Fragrance Industry ...............................................270 II. PATENT AND COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR FRAGRANCES ............................273 A. Patent ......................................................................................................273 B. Copyright ................................................................................................276 C. France and the Netherlands: Odor in the Courts ..................................280 III. FRAGRANCE AND TRADEMARK PROTECTION ................................................283 A. The Expanding Scope of Trademark Protection ....................................283 -

Aesthetic and Social Constructions of Fragrance

Linguistic and Social Constructions of Fragrance Some Preliminary Thoughts on Entering the Field Moeran, Brian Document Version Final published version Publication date: 2004 License CC BY-NC-ND Citation for published version (APA): Moeran, B. (2004). Linguistic and Social Constructions of Fragrance: Some Preliminary Thoughts on Entering the Field. Link to publication in CBS Research Portal General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us ([email protected]) providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 Department of Intercultural Communication and Management Dalgas Have 15 DK-2000 Frederiksberg Working Paper no 77, 2004 Linguistic and Social Constructions of Fragrance: Some Preliminary Thoughts on Entering the Field Brian Moeran Professor [email protected] 0 Linguistic and Social Constructions of Fragrance: Some Preliminary Thoughts on Entering the Field Brian Moeran Copenhagen Business School [email protected] Absolutely not to be quoted without permission, please Preamble The theoretical discourses devoted to smell reflect a maze of fascinating taboos and mysterious attractions. In present-day Western societies, the sense of smell is undervalued. Scents are highly elusive and often cannot be directly named. Many languages have virtually no vocabulary to describe them, except in terms of the other senses of sight, sound, touch and taste. -

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury

1 FAHRENHEIT 451 By Ray Bradbury This one, with gratitude, is for DON CONGDON. FAHRENHEIT 451: The temperature at which book- paper catches fire and burns 2 PART I IT WAS A PLEASURE TO BURN IT was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history. With his symbolic helmet numbered 451 on his stolid head, and his eyes all orange flame with the thought of what came next, he flicked the 3 igniter and the house jumped up in a gorging fire that burned the evening sky red and yellow and black. He strode in a swarm of fireflies. He wanted above all, like the old joke, to shove a marshmallow on a stick in the furnace, while the flapping pigeon- winged books died on the porch and lawn of the house. While the books went up in sparkling whirls and blew away on a wind turned dark with burning. Montag grinned the fierce grin of all men singed and driven back by flame. He knew that when he returned to the firehouse, he might wink at 4 himself, a minstrel man, burnt- corked, in the mirror. Later, going to sleep, he would feel the fiery smile still gripped by his face muscles, in the dark. -

Maestro Profumiere

Fragranze & profumi ■ di Silvio Levi Maestro profumiere Edmond Roudniska è stato quasi certamente la figura più determinante pubblico: “Le concentrazioni così alte dei profumi, …. sono dovute per la creatività olfattiva moderna. Uno dei più grandi compositori da due convinzioni erronee. La prima è legata alla (non conoscenza dei nostri tempi, le cui creazioni sono tutte dei capolavori e molte della) legge di Fechner, che ho spiegato in Esthétique en Question: la sono ancora in produzione. Traqueste Femme (Rochas-1944), Eau percezione aumenta in funzione del logaritmo della concentrazione. d’Hermés (Hermés-1951), Diorissimo (Dior-1956), Eau Sauvage (Dior- Ciò significa che se la concentrazione passa da 1 a 16, per esempio, 1966), Diorella (Dior-1972). Oltre ai suoi innegabili meriti compositivi, la corrispondente percezione crescerà solo da 1 a 5. La seconda a Edmond Roudnitska dobbiamo l’impegno a favore dell’estetica convinzione erronea deriva dalla non conoscenza del meccanismo della composizione olfattiva, al suo ruolo di comprimaria tra le arti regolatore del nostro sistema ricevente olfattivo, che amplifica gli compositive. “La forma di un profumo deriva da una combinazione odori che sono troppo deboli ma inibisce la ricezione degli odori estetica scelta e voluta dal profumiere. La formulazione della troppo forti. Sovra concentrare le fragranze è denaro buttato che fragranza è il risultato di una combinazione di costituenti che potrebbe essere usato meglio per lavorare su meravigliosi prodotti, danno origine a un fenomeno complessivo che è tutto fuorché la ideati da compositori artisti, e farli pervenire alla clientela che li semplice somma (degli ingredienti)”2. O ancora: “Un bel profumo saprebbe apprezzare. -

Gold Star Fragrances Catalog Order Information

Gold Star Fragrances Catalog Date: 2021/10/02 This catalog lists all fragrance oils available online at the time of printing. It does not reflect the prices of related Incense Oil, Massage Oil, Body Lotion and Shampoo available in 16-ounce bottles. The prices shown reflect the 1-, 4-, 8- and 16-ounce fragrance oil sizes. (In some instances the sizes may also be referred to as quarter pound (4 oz), half pound (8 oz) and one pound (16 oz) sizes which is based on shipping weight not liquid content. You can view prices of related options online in QuikScent by clicking on the fragrance oil. The prices and fragrances are subject to change online notice. Order Information You can order online at www.goldstarfragrances.com, or by calling Gold Star Fragrances at: 212-279-4474. You can also order in person at our store located at 8 West 37th Street, NY, NYC 10018. Disclaimer: The catalog does not claim that the list of oils or perfumes are the brand shown. The brand names shown are the property of the respective owner. This list is provided only to show a similarity to the scent as indicates by the word “Type.” © 2016 Gold Star Fragrances, Inc. All rights reserved. FAM5704MA: 03# 1789 Inspired by * 3:AM by Sean John [MA], $4.95, $14.75, $29.00, $56.00. F21101FE: 22# 101 Inspired by * 212 by Carolina Herrera [FE], $4.95, $14.75, $29.00, $56.00. F21351MA: 22# 351 Inspired by * 212 by Carolina Herrera [MA] , $4.95, $14.75, $29.00, $56.00. -

Louis Vuitton

LVMH_RA_09_GB:Mise en page 1 26/02/10 11:13 Page1 LVMHPassionate about creativity ANNUAL REPORT LVMH_RA_09_GB:Mise en page 1 26/02/10 11:13 Page2 Contents 02 Chairman’s Message 06 Financial Highlights 08 Interview with Antonio Belloni: New expectations for luxury 10 Corporate Governance 12 The LVMH Share 14 Review of operations 16 24 16 Wines & Spirits 24 Fashion & Leather Goods 32 Perfumes & Cosmetics 40 Watches & Jewelry 46 Selective Retailing 52 Sustainable development 54 Our Code of Conduct 55 Human resources Contributing to the future of tradition 63 Corporate sponsorship to support culture, youth and humanitarian action 64 Protecting the environment 71 Consolidated Financial Statements LVMH_RA_09_GB:Mise en page 1 26/02/10 11:13 Page3 4324046 01 PASSIONATE ABOUT CREATIVITY LVMH_RA_09_GB:Mise en page 1 26/02/10 11:13 Page4 WITH TALENT AND DISCIPLINE, OUR TEAMS HAVE RESPONDED TO THE CHALLENGE Bernard Arnault We took advantage of this turbulent period, during which our clients sought a return to core values, to recall our heritage of excellence, and the values of creativity and durability which are embodied by the Group’s brands. The future holds excellent potential, in historic markets as well as in emerging markets, for brands which know how to continually inspire their contemporaries, regardless of where they are in the world, and are committed to quality, beauty and authenticity. PASSIONATE ABOUT CREATIVITY LVMH_RA_09_GB:Mise en page 1 26/02/10 11:13 Page5 A commitment to youth: At the end of a year marked by an unprece- LVMH’s “Discovery and Learning” classes dented global crisis, our Group responded organized during exhibits supported by the Group to the challenge set and increased its market have been attended by over 20,000 children share. -

Cis-2-Pentenyl Pentanolide

Index A α,α-Diethylpyridine (Verdima), 261–262 Abril, 183 Absolu de Rochas, 195 Absolute of Jasmine (cis-2-pentenyl pentanolide), 40 Acetal E (acetaldehyde phenyl ethyl-ethyl acetal), 45 Acetal R (phenylethyl-alpha-propyl acetal), 45 acetaldehyde (Elintaal), 14, 45 acetals, 17 Acetomarane, 23 acetyl guaiacol (II), 106 acetyl thujopsene, 27 acetyl-1 ,5,9-trimethyl-1-5-9 cyclododecatriene (Trimofix), 28 acid, food, lactone and carmelized family, 64 α-Damascone thiomethyl ether, 69 α-Damascone [1-(2,6,6-trimethyl-2-cyclohexen-1-yl)-2-buten-1-one], 15, 19, 41, 43, 81 Adoxal (trimethylundecylenic aldehyde), 17 Agarwood, 87 agrestical family, 3, 4–5, 23–25, 50–52, 84–91, 147–154 Agrumal, 17, 125 Agrumen, 17 Agrunitril (citronellyl nitrile), 37 Agua Brava, 48 Agua Fresca by Adolfo Dominguez, 95 α-Hexyl-χ-butyrolactone, 68 α-Ionol, 247 α-Ionyl acetate, 247–248 Aire de Loewe, 116, 239 Aladinate (3-methyl-2-hexenyl acetate), 264 alcohol NU (5-ethyl-2-nonanol), 128, 212 aldehyde C.13, 5 aldehyde family, 3, 5–6, 26, 59–60, 91–92, 155–157 Aldehyde NU, 128 Aldehyde XI (p-Methylphenoxyacetaldehyde), 119 Algia, 76 algoid and marine odors, 32 Alkanyl acetate, 76 271 Perfumery: Techniques in Evolution alkoxypyrazines, 18, 44 Alliage, 42, 59, 66, 72, 73, 117 allo ocimenol (Muguol), 12 allyl cyclohexyl propionate, 43 allyl heptylate, 43 allyl phenoxyacetate, 43 allyl tiglate, 24 Alpha-Ambrinol epoxide (2-hydroxy-2,5,5-trimethyl-8,8-A-epoxy octaline), 32 alpha-cedrene epoxide (Andrane), 6, 27 alpha-hexyl-gamma-butyrolactone, 41 alpha-ionone, 16 alpha-methylene -

Dior Cosmetics, Fragrances & More Ingredients List

Dior Cosmetics, Fragrances & More Ingredients List 1 Synthetic fluorphlogopite, talc, boron nitriqe, barium sulfate, diphenyl dimethiconeninyl diphenyl dimethicone/silsesquioxane crosspolymer, nylon-12, octylex)decyl stearoyl stearate, magnesium myristate, phenyl trimethicone, acrylates/stbnftyl acrylate/dimeihicone methacrylate copolymer, calcium aluminum borosilicate, pentylene glycol, hdi/trimethylcl hexyllactone crosspolymer, dimethicone, lauroyl lysine, sodium dehydroacetate, silica, hydrogen dimethicone, tin oxide, palmitic acid, magnesium hydroxide n 09384/a. 2 Synthetic fluorphlogopite, dimethicone, talc, diisostearyl malate, methyl methacrylate crosspolymer, petrolatum, mica, trimethylolpropane triethylhexanoate, magnesium myristate, hdi/ppg/ polycaprolactone crosspolymer, sorbitan sesquiisostearate, siuca, trimethylsiloxysilicate, polypropyl, silsesqumane, sodium dehydroacetate, sorbic acid, ethylhexylglycerin, glyceryl caprylate, tocopherol n 09458/a. 3 Dimethicone, mica, talc, diisostearyl malate, synthetic fluorphlogopite, methyl methacrylate crosspolymer, petrolatum, trimethylolpropane triethylhexanoate, magnesium myristate, hdi/ppg/ polycaprolactone crosspolymer, silica, sorbitan sesquiisostearate, trimethylsiloxysilicate, polypropyl- silsesquioxane, sodium dehydroacetate, sorbic acid, lauroyl lysine, ethylhexylglycerin, glyceryl caprylate, tin oxide, tocopherol, n 09451/a. 5 Color Designer All In One Artistry Palette - 4 Dimethicone, talc, calcium sodium borosilicate, silica, No. 208 Navy Design diisostearyl malate, petrolatum,