Aesthetic and Social Constructions of Fragrance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zapachy Damskie

ZAPACHY DAMSKIE 161 HEAT Beyonce 073 DKNY BE DELICIOUS DKNY 151 TOUCH OF PINK Lacoste 107 BOTTEGA VENETA Bott. Veneta 030 NECTAR LOVE DKNY 156 INSPIRATION Lacoste 019 BRUNO BANANI Bruno Banani 061 GREEN TEA E.Arden 131 FAME Lady Gaga 123 MADE FOR WOMEN Bruno Banani 127 5th AVENUE E.Arden 076 MIRACLE Lancome 102 CHRISTINA AGUILERA C. Aguilera 039 DESIRE ME Escada 092 HYPNOSE Lancome 117 212 VIP C.Herrera 047 INTO THE BLUE Escada 101 LA VIE EST BELLE Lancome 160 212 WOMAN C.Herrera 072 BORN IN PARADISE Escada 199 LA VIE EST BELLE L`eclat Lancome 170 212 VIP ROSE C.Herrera 190 MODERN MUSE LE ROUGE Estee Lauder 109 POEME Lancome 183 GOOD GIRL C.Herrera 189 BECAUSE IT` YOU G.Armani 141 TRESOR Lancome 012 DIOR ADDICT C.Dior 010 SENSI G.Armani 175 LA NUIT TRESOR Lancome 044 MIDNIGHT POISON C.Dior 040 EMPORIO DIAMONDS G.Armani 084 ECLAT D’ARPEGE Lanvin 080 DUNE C.Dior 041 ARMANI MANIA G.Armani 001 DAISY Marc Jacobs 082 MISS DIOR CHERIE C.Dior 110 ACQUA DI GIO G.Armani 186 DECADENCE Marc Jacobs 196 MISS DIOR LE PARFUM C.Dior 111 IDOLE G.Armani 035 LOLA Marc Jacobs 093 POISON C.Dior 100 SI PASSIONE G.Armani 063 LE PARFUM Max Mara 116 DOLCE VITA C.Dior 129 SI G.Armani 172 L`EAU Mercedes 145 HYPNOTIC POISON C.Dior 135 ARMANI CODE G.Armani 124 MEXX WOMAN Mexx 159 J’ADORE C.Dior 146 ACQUA DI GIOIA G.Armani 005 JASMINE GLAM Michael Kors 188 J’ADORE IN JOY C.Dior 150 EMPORIO SHE G.Armani 171 SEXY AMBER Michael Kors 176 POISON GIRL C.Dior 053 BOLERO G.Sabatini 104 L’EAU D’ISSEY Miyake 028 DOWNTOWN C.K 090 GABRIELA SABATINI G.Sabatini 011 I LOVE Moschino -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,189,810 B1 Nerushai Et Al

USOO618981 OB1 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,189,810 B1 Nerushai et al. (45) Date of Patent: Feb. 20, 2001 (54) METHOD FOR AEROSOLSPRAYING 5,746,354 * 5/1998 Perkins ................................. 222/135 LIQUID PERFUME PRODUCTS 5,772,074 6/1998 Dial et al. ............................ 222/646 (76) Inventors: Sergei Alexeevich Nerushai, Russia, FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS 140000, Moskovskaya oblast, Ljubertsy, 2563 981 11/1985 (FR). Komsomolsky prospekt, Moscow (RU); 2586 913 3/1987 (FR). Nurakhmed Nurislamovich Latypov, 5Voikovsky proezd.d.10, kV.31, Moscow * cited by examiner 125171 (RU) Primary Examiner Andres Kashnikow Assistant Examiner Dinh Q. Nguyen (*) Notice: Under 35 U.S.C. 154(b), the term of this (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Burns, Doane, Swecker & patent shall be extended for 0 days. Mathis, L.L.P. (21) Appl. No.: 09/401,372 (57) ABSTRACT (22) Filed: Sep. 22, 1999 A method for aeroSol Spraying liquid perfume products consists of Simultaneously spraying liquid perfume products (30) Foreign Application Priority Data and/or components of liquid perfume products, having dif Oct. 7, 1998 (RU) ................................................ 98118182 ferent odors, in the form of aeroSol Streams into a region being treated. AeroSol Spraying nozzles are placed proxi (51) Int. Cl." ................................................. A62C 13/62 mate each other. The Simultaneous spraying of at least two (52) U.S. Cl. .......................... 239,306; 239/337; 239/433; components of a liquid perfume product is carried out, and 222/135; 222/402.1 during the Spraying the axes of the aeroSol Streams of the (58) Field of Search ..................................... 239/306, 337, components are positioned at an angle to each other that 239/418, 433, 543, 544; 222/137, 132, ensures interSection of the aeroSol Streams. -

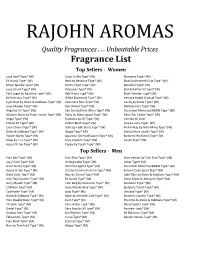

Fragrance List Print

Quality Fragrances . Unbeatable Prices Fragrance List Top Sellers - Women Love Spell Type* (W) Gucci Guilty Type* (W) Romance Type* (W) Ed Hardy Type*RAJOHN (W) Heat by Beyonce Type* (W)AROMASBlack by Kenneth Cole Type* (W) Moon Sparkle Type* (W) Jimmy Choo Type* (W) Beautiful Type* (W) Love Struck Type* (W) Pleasures Type* (W) Bombshell by VS Type* (W) Pink Sugar by Aquolina Type* (W) Reb'l Fleur Type* (W) Black Woman Type* (W) Be Delicious Type* (W) White Diamonds Type* (W) Versace Bright Crystsal Type* (W) Light Blue by Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Cashmere Mist Type* (W) Candy by Prada Type* (W) Issey Miyake Type* (W) Butt Naked Type* (W) Michael Kors Type* (W) Angel by VS Type* (W) Can Can by Paris Hilton Type* (W) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* (W) Modern Muse by Estee Lauder Type* (W) Daisy by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Miss Dior Cherie Type* (W) Angel Type* (W) Euphoria by CK Type* (W) Lick Me All Over Chanel #5 Type* (W) Amber Blush Type* (W) Viva La Juicy Type* (W) Coco Chanel Type* (W) Halle by Halle Berry Type* (W) Pink Friday by Nicki Minaj Type* (W) Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Happy Type* (W) Dot by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Flower Bomb Type* (W) Japanese Cherry Blossom Type* (W) Burberry Weekend Type* (W) Glow by J. Lo Type* (W) Juicy Couture Type* (W) Coach Type* (W) Acqua Di Gio Type* (W) Poppy by Coach Type* (W) Top Sellers - Men Polo Red Type* (M) Polo Blue Type* (M) Grey Vetiver by Tom Ford Type* (M) Jay-Z Gold Type* (M) Unforgivable Type* (M) Usher Type* (M) Gucci Guilty Type* (M) Chrome Legend Type* (M) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* -

Paco Rabanne

HERSTELLER DUFT NR PRODUKTART Aerin Amber Musk 834 PR Aventus Creed 372 P KS Bottega Veneta 819 PR Burberry The Beat 239 P Burberry London 257 P Byredo Bal D´Afrique 709 PR Cacharel Amore Amore 23 P PP PI Calvin Klein Eternity Flame 484 P Euphoria 171 PR DG Deep Euphoria 802 PR Carolina Herrera Good Girl 431 P PP 212 714 PR Cerruti Cerruti 1881 706 P Chanel Coco Mademoiselle 18 P PP PI DG BL DR KS RS No.5 21 P PI No.5 Red Limited Edition 826 PR Chance 34 P PP Chance eau Fraiche 707 PR Chance eau Tendre 322 PR Coco Noir 365 PR Gabrielle 800 PR Chloé L´Eau de Chloe 488 P Love Story 807 PR Nomade 447 P Christina Aguilera Christina Aguillera 237 P Davidoff Cool Water 419 P Dior Addict 142 PR Cherie 80 P Dune 825 PR Hypnotic Poison 173 P PI DG BL DR Jádore 10 P PP PI J´adore In Joy 806 PR Joy 445 P Midnight Poison 286 PR HERSTELLER DUFT NR PRODUKTART Dior Miss Dior Absolute Blooming 427 P Miss Dior 432 P Miss Dior 2017 801 PR Miss Dior Blooming Bouquet 810 PR Miss Dior Rose N´Roses 848 PR NEU Poison Girl 434 P DKNY Be Delicious 81 P PP PI DG BL DR Golden Delicious 443 P Dolce & Gabbana Light Blue 33 P PP PI DG BL DR The One 147 PR 3 L`Imperatrice 701 P Peony 836 PR The Only One 444 P Donna Trussardi Donna 355 PR Elisabeth Arden Green Tea 6 P Ellie Saab Le Parfum 352 PR Emporio Armani Because It´s You 817 PR Diamonds 180 P Escada Moon Sparkle 281 PR Estee Lauder Modern Muse 715 PR Ex Nihilo Fleur Narcotique 708 PR Giorgio Armani Aqua di Gio 7 P Armani Code 101 P PP Mania 177 P My Way 847 PR NEU Si 362 PR Cashmere 438 P Si Intense 804 PR Givenchy -

Journal of Intellectual Property and Entertainment Law

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND ENTERTAINMENT LAW VOLUME 5 FALL 2015 NUMBER 1 LOST AND FOUND: INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY OF THE FRAGRANCE INDUSTRY; FROM TRADE SECRET TO TRADE DRESS CHARLES CRONIN* INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................257 I. THE FRAGRANCE INDUSTRY AND THE CHALLENGE OF REVERSE ENGINEERING ................................................................................................263 A. Regulation of Reverse Engineering in the United States and the European Union .....................................................................................263 B. Challenges to the Fragrance Industry’s Traditional Reliance on Trade Secrets ..........................................................................................267 C. The Impact of Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Technologies on the Fragrance Industry ...............................................270 II. PATENT AND COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR FRAGRANCES ............................273 A. Patent ......................................................................................................273 B. Copyright ................................................................................................276 C. France and the Netherlands: Odor in the Courts ..................................280 III. FRAGRANCE AND TRADEMARK PROTECTION ................................................283 A. The Expanding Scope of Trademark Protection ....................................283 -

Maestro Profumiere

Fragranze & profumi ■ di Silvio Levi Maestro profumiere Edmond Roudniska è stato quasi certamente la figura più determinante pubblico: “Le concentrazioni così alte dei profumi, …. sono dovute per la creatività olfattiva moderna. Uno dei più grandi compositori da due convinzioni erronee. La prima è legata alla (non conoscenza dei nostri tempi, le cui creazioni sono tutte dei capolavori e molte della) legge di Fechner, che ho spiegato in Esthétique en Question: la sono ancora in produzione. Traqueste Femme (Rochas-1944), Eau percezione aumenta in funzione del logaritmo della concentrazione. d’Hermés (Hermés-1951), Diorissimo (Dior-1956), Eau Sauvage (Dior- Ciò significa che se la concentrazione passa da 1 a 16, per esempio, 1966), Diorella (Dior-1972). Oltre ai suoi innegabili meriti compositivi, la corrispondente percezione crescerà solo da 1 a 5. La seconda a Edmond Roudnitska dobbiamo l’impegno a favore dell’estetica convinzione erronea deriva dalla non conoscenza del meccanismo della composizione olfattiva, al suo ruolo di comprimaria tra le arti regolatore del nostro sistema ricevente olfattivo, che amplifica gli compositive. “La forma di un profumo deriva da una combinazione odori che sono troppo deboli ma inibisce la ricezione degli odori estetica scelta e voluta dal profumiere. La formulazione della troppo forti. Sovra concentrare le fragranze è denaro buttato che fragranza è il risultato di una combinazione di costituenti che potrebbe essere usato meglio per lavorare su meravigliosi prodotti, danno origine a un fenomeno complessivo che è tutto fuorché la ideati da compositori artisti, e farli pervenire alla clientela che li semplice somma (degli ingredienti)”2. O ancora: “Un bel profumo saprebbe apprezzare. -

THE POLLUTANT PERFUME – Poison by Christian Dior, 1985

THE POLLUTANT PERFUME – Poison by Christian Dior, 1985 Mid-eighties mainstream Hollywood loved covering the workplace. It especially loved the revamped New York fairy tale that saw the lowly secretary make it onto the board against the odds and get off with the company vice president. Our heroine would invariably be shown racing out of the subway in her white trainers and then hobbling along the street as she got in to her stilettos ready for the revolving doors of her office block. For every screen treatment of a woman fighting to get to the top, there was another which zoomed in on the post-Happy Ever After moment, in which the female boss at the pinnacle of her career had become a heartless bitch or lost soul, in need of a lesson about real values. Baby Boom from 1987, for example, tells the story of a tough management consultant, played by Diane Keaton, retreating from the boardroom to Vermont, where she makes gourmet baby food, rediscovers herself and falls in love with a kind vet. In 1988’s Big, it is toy-company executive Susan who, burned out by the end of her twenties, needs a boy-turned-man in the form of Tom Hanks to remind her about joy, fun and the pleasures of bouncing on trampolines. To establish just how bitchy they were pre-makeover, these divas resorted to a number of easy-to- interpret shorthand gestures. One such was the overt waving about of a perfume bottle – especially effective if it was an atomiser with a squeezy bulb. -

Cis-2-Pentenyl Pentanolide

Index A α,α-Diethylpyridine (Verdima), 261–262 Abril, 183 Absolu de Rochas, 195 Absolute of Jasmine (cis-2-pentenyl pentanolide), 40 Acetal E (acetaldehyde phenyl ethyl-ethyl acetal), 45 Acetal R (phenylethyl-alpha-propyl acetal), 45 acetaldehyde (Elintaal), 14, 45 acetals, 17 Acetomarane, 23 acetyl guaiacol (II), 106 acetyl thujopsene, 27 acetyl-1 ,5,9-trimethyl-1-5-9 cyclododecatriene (Trimofix), 28 acid, food, lactone and carmelized family, 64 α-Damascone thiomethyl ether, 69 α-Damascone [1-(2,6,6-trimethyl-2-cyclohexen-1-yl)-2-buten-1-one], 15, 19, 41, 43, 81 Adoxal (trimethylundecylenic aldehyde), 17 Agarwood, 87 agrestical family, 3, 4–5, 23–25, 50–52, 84–91, 147–154 Agrumal, 17, 125 Agrumen, 17 Agrunitril (citronellyl nitrile), 37 Agua Brava, 48 Agua Fresca by Adolfo Dominguez, 95 α-Hexyl-χ-butyrolactone, 68 α-Ionol, 247 α-Ionyl acetate, 247–248 Aire de Loewe, 116, 239 Aladinate (3-methyl-2-hexenyl acetate), 264 alcohol NU (5-ethyl-2-nonanol), 128, 212 aldehyde C.13, 5 aldehyde family, 3, 5–6, 26, 59–60, 91–92, 155–157 Aldehyde NU, 128 Aldehyde XI (p-Methylphenoxyacetaldehyde), 119 Algia, 76 algoid and marine odors, 32 Alkanyl acetate, 76 271 Perfumery: Techniques in Evolution alkoxypyrazines, 18, 44 Alliage, 42, 59, 66, 72, 73, 117 allo ocimenol (Muguol), 12 allyl cyclohexyl propionate, 43 allyl heptylate, 43 allyl phenoxyacetate, 43 allyl tiglate, 24 Alpha-Ambrinol epoxide (2-hydroxy-2,5,5-trimethyl-8,8-A-epoxy octaline), 32 alpha-cedrene epoxide (Andrane), 6, 27 alpha-hexyl-gamma-butyrolactone, 41 alpha-ionone, 16 alpha-methylene -

Dior Cosmetics, Fragrances & More Ingredients List

Dior Cosmetics, Fragrances & More Ingredients List 1 Synthetic fluorphlogopite, talc, boron nitriqe, barium sulfate, diphenyl dimethiconeninyl diphenyl dimethicone/silsesquioxane crosspolymer, nylon-12, octylex)decyl stearoyl stearate, magnesium myristate, phenyl trimethicone, acrylates/stbnftyl acrylate/dimeihicone methacrylate copolymer, calcium aluminum borosilicate, pentylene glycol, hdi/trimethylcl hexyllactone crosspolymer, dimethicone, lauroyl lysine, sodium dehydroacetate, silica, hydrogen dimethicone, tin oxide, palmitic acid, magnesium hydroxide n 09384/a. 2 Synthetic fluorphlogopite, dimethicone, talc, diisostearyl malate, methyl methacrylate crosspolymer, petrolatum, mica, trimethylolpropane triethylhexanoate, magnesium myristate, hdi/ppg/ polycaprolactone crosspolymer, sorbitan sesquiisostearate, siuca, trimethylsiloxysilicate, polypropyl, silsesqumane, sodium dehydroacetate, sorbic acid, ethylhexylglycerin, glyceryl caprylate, tocopherol n 09458/a. 3 Dimethicone, mica, talc, diisostearyl malate, synthetic fluorphlogopite, methyl methacrylate crosspolymer, petrolatum, trimethylolpropane triethylhexanoate, magnesium myristate, hdi/ppg/ polycaprolactone crosspolymer, silica, sorbitan sesquiisostearate, trimethylsiloxysilicate, polypropyl- silsesquioxane, sodium dehydroacetate, sorbic acid, lauroyl lysine, ethylhexylglycerin, glyceryl caprylate, tin oxide, tocopherol, n 09451/a. 5 Color Designer All In One Artistry Palette - 4 Dimethicone, talc, calcium sodium borosilicate, silica, No. 208 Navy Design diisostearyl malate, petrolatum, -

CHRISTIAN DIOR – Esprit De Parfums

GrasseLe goût de l’essentiel CHRISTIAN DIOR – Esprit de Parfums INTERNATIONAL PERFUME MUSEUM - GRASSE PRESS RELATIONS: Muriel Courché Head of communication Tel.: +33 (0)4 97 05 22 03 – Port.: +33 (0)6 68 93 02 42 [email protected] GENERAL CURATOR: Olivier Quiquempois, Director of the Museums of Grasse, Curator of Heritage, SCIENTIFIC CURATOR: Grégory Couderc, Assistant Curator of Heritage, Scientific Director, International Perfume Museum, Grasse Vincent Leret, Director of Heritage and Collections, Christian Dior Parfums SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE: Frédéric Bourdelier, Director of Brand Culture & Heritage, Christian Dior Parfums Nathalie Derra, Head of Exhibitions and Patronage, International Perfume Museum, Grasse Chloé Fargier, Archivist, International Perfume Museum, Grasse Cindy Levinspuhl, Head of Exhibitions and Museography, International Perfume Museum, Grasse CONCEPTION: Pays de Grasse Regional Communication Directorate, Photography Laziz Hamani Press kit - “Christian Dior: Esprit de Parfums” - International Perfume Museum 2 CONTENTS Christian Dior: Esprit de Parfums Foreword P. 4 The exhibition at a glance P. 5 Exhibition structure P. 6 Acknowledgments P. 11 Practical information P. 12 Press kit - “Christian Dior: Esprit de Parfums” - International Perfume Museum 3 Foreword Christian Dior: Esprit de Parfums Christian Dior founded his fashion house in Paris in October 1946, and showcased his first collection on 12 February 1947. The event was a dazzling success, and was to make a lasting impression. Ten years later, Christian Dior passed away suddenly and unexpectedly in Montecatini in Italy on 24 October 1957, lending a new dimension to the fleeting decade and extraordinary life of the artist. From 1957 on, the Maison Dior’s adventure continued, with fragrance playing a leading role in the way in which Dior’s brand image was to unfurl. -

Christian Dior / Evora

BENELUX-GERECHTSHOF COUR DE JUSTICE BENELUX A 95/4/14 ARREST van 16 december 1998 in de zaak A 95/4 -------------------------- Inzake : Christian Dior N.V. tegen Evora B.V. Procestaal : Nederlands ARRET du 16 décembre 1998 dans l’affaire A 95/4 ----------------------------- En cause : Christian Dior S.A. contre Evora B.V. Langue de la procédure : le néerlandais 2 HET BENELUX-GERECHTSHOF In de zaak A 95/4 1. Gelet op het op 20 oktober 1995 door de Hoge Raad der Nederlanden uitgesproken arrest in de zaak nr. 15.735 van PARFUMS CHRISTIAN DIOR S.A., gevestigd te Parijs, en PARFUMS CHRISTIAN DIOR B.V., gevestigd te Rotterdam, eiseressen tot cassatie (hierna afzonderlijk te noemen : Dior Frankrijk, respectievelijk Dior Nederland en gezamenlijk : Dior), tegen EVORA B.V., gevestigd te Renswoude, verweerster in cassatie (verder te noemen : Evora), waarbij overeenkomstig artikel 6 van het Verdrag betreffende de instelling en het statuut van een Benelux-Gerechtshof aan dit Hof vragen van uitleg van de Eenvormige Beneluxwet op de merken (BMW) worden gesteld; TEN AANZIEN VAN DE FEITEN: 2. Overwegende dat de Hoge Raad de feiten waarop de door het Benelux- Gerechtshof te geven uitleg moet worden toegepast, als volgt heeft omschreven: i) Dior Frankrijk ontwikkelt en produceert verscheidene parfums en andere cosmetische producten die zij onder verschillende merken op de markt brengt. Deze producten hebben een relatief hoge prijs en worden gerekend tot de markt van de luxueuze cosmetische producten. ii) Dior Frankrijk heeft voor de verkoop van haar producten in landen buiten Frankrijk alleenvertegenwoordigers aangesteld; Dior Nederland is in Nederland zulk een alleenvertegenwoordiger. -

TRANSLATION of the FRENCH DOCUMENT De Reference FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2009 Contents

TRANSLATION OF THE FRENCH DOCUMENT DE REFERENCE FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2009 Contents LVMH GROUP 1 History 1 Financial higHligHts 2 ExEcutive and SupErvisory BodiEs; Statutory Auditors 5 simpliFiEd organizational cHart 6 BusinEss dEscription 9 MANAGEMENT REPORT OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS 23 LVMH Group 23 parEnt company: lvmh moEt hennEssy - louis vuitton SA 49 Human rEsourcEs 67 LVMH and the environmEnt 83 REPORT OF THE CHAIRMAN OF BOARD OF DIRECTORS 97 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 109 consolidatEd financial statEmEnts 109 parEnt company financial statEmEnts: lvmh moEt hennEssy - louis vuitton sa 179 OTHER INFORMATION 205 corporate govErnancE 205 GenEral inFormation rEgarding the parEnt company; stock markEt inFormation 233 Resolutions for the approval of the combined shareholders’ meeting of April 15, 2010 241 RESPONSIBLE COMPANY OFFICER; FINANCIAL INFORMATION 247 TABLES OF CONCORDANCE 251 This document is a free translation into English of the original French “Document de Référence”, hereafter referred to as the “Reference Document”. It is not a binding document. In the event of a conflict in interpretation, reference should be made to the French version, which is the authentic text. LVMH group HistoRy Although the history of the LVMH Group began in 1987 with the merger of Moët Hennessy and Louis Vuitton, the roots of the Group actually stretch back much further, to eighteenth-century Champagne, when a man named Claude Moët decided to build on the work of Dom Pérignon, a contemporary of Louis XIV; and to nineteenth-century Paris, famous for its imperial celebrations, where Louis Vuitton, a craftsman trunk-maker, invented modern luggage. Today, the LVMH Group is the world’s leading luxury goods company, the result of successive alliances among companies that, from generation to generation, have successfully combined traditions of excellence and creative passion with a cosmopolitan flair and a spirit of conquest.