Parfums Christian Dior Sa & (And) Anor V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury This One, with Gratitude, Is for DON CONGDON

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury This one, with gratitude, is for DON CONGDON. FAHRENHEIT 451: The temperature at which book-paper catches fire and burns PART I: THE HEARTH AND THE SALAMANDER IT WAS A PLEASURE TO BURN. IT was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history. With his symbolic helmet numbered 451 on his stolid head, and his eyes all orange flame with the thought of what came next, he flicked the igniter and the house jumped up in a gorging fire that burned the evening sky red and yellow and black. He strode in a swarm of fireflies. He wanted above all, like the old joke, to shove a marshmallow on a stick in the furnace, while the flapping pigeon- winged books died on the porch and lawn of the house. While the books went up in sparkling whirls and blew away on a wind turned dark with burning. Montag grinned the fierce grin of all men singed and driven back by flame. He knew that when he returned to the firehouse, he might wink at himself, a minstrel man, Does% burntcorked, in the mirror. Later, going to sleep, he would feel the fiery smile still gripped by his Montag% face muscles, in the dark. -

Parfums Christian Dior Appoints New Brand General Director – WWD 1/3/2020, 8:31 PM

Parfums Christian Dior Appoints New Brand General Director – WWD 1/3/2020, 8:31 PM BEAUTY / BEAUTY FEATURES Parfums Christian Dior Names New Brand General Director Claudia Marcocci has been appointed to the position, succeeding Véronique Courtois. By Jennifer Weil on February 25, 2020 ESSENTIALIST TODAY'S MUST READ Hermes RTW Fall 2020 LATEST GALLERIES Claudia Marcocci Courtesy Photo PARIS — Claudia Marcocci has been appointed brand general director of Parfums Christian Dior. She took up the position on Feb. 15, succeeding Véronique Courtois, who had held the job for more than seven years before moving to steer Guerlain, another LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton-owned brand. Backstage at Elie Saab RTW Marcocci was formerly senior vice president of Gucci Beauty, Fall 2020 beginning in 2017, at Coty Inc. She also served as vice president of global for that brand, starting in 2016, and the year prior https://wwd.com/beauty-industry-news/beauty-features/parfums-christian-dior-names-new-brand-general-director-1203509974/ Page 1 of 5 Parfums Christian Dior Appoints New Brand General Director – WWD 1/3/2020, 8:31 PM became associate director of Gucci Beauty global design after the Procter & Gamble beauty brands were acquired by Coty. Marcocci held numerous positions at P&G, including global digital and e-commerce director for its prestige division. LVMH’s Perfumes and Cosmetics Division closed 2019 with sales of 6.84 billion euros, up 12 percent year-over-year in reported terms and 9 percent on an organic basis. The company cited Dior as a main growth driver for the branch, and said the brand’s business grew much faster than the beauty market. -

Christian Dior Why Would Bernard Arnault Invest

A work project, presented as part of the requirements for the Award of a Master Degree in International Finance from the NOVA – School of Business and Economics CHRISTIAN DIOR WHY WOULD BERNARD ARNAULT INVEST BILLIONS ON A NAME HE ALREADY HOLDS? CAROLINA MARQUES BARREIROS – 4134 / 24015 A Project carried out on the Master in Finance Program, under the supervision of: Paulo Pinho January 2019 Tuesday, April 25th 2017i. Bernard Arnault decided to go shopping. On the menu, a double operation that aims to simplify the ties that unite the group LVMH (Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton), Christian Dior and its owner Bernard Arnault. The first transaction consists of an offer worth about €12.1 billion from the holding company controlled by Arnault Family Group to take over of the remaining 25.9% stake Christian Dior. The second one on the strengthening of LVMH group through the acquisition of the Christian Dior Couture for €6.5 billionii. However, a question remains: why would Bernard Arnault invest billions on a name he already holds? LVMH “The LVMH group is the world’s leading luxury goods company, the result of successive alliances among companies that, from generation to generation, have successfully combined traditions of excellence and creative passion with a cosmopolitan flair and a spirit of conquest.” - LVMH websiteiii Born out of the merger of Louis Vuitton and the Moët Hennessy group in 1987, the LVMH group led by Bernard Arnault is the world’s largest luxury conglomerate in terms of turnover (Exhibit 1). In 2016, the consolidated revenue of LVMH group was €37.6 billioniv, 5% more than in 2015 (Exhibit 2). -

Zapachy Damskie

ZAPACHY DAMSKIE 161 HEAT Beyonce 073 DKNY BE DELICIOUS DKNY 151 TOUCH OF PINK Lacoste 107 BOTTEGA VENETA Bott. Veneta 030 NECTAR LOVE DKNY 156 INSPIRATION Lacoste 019 BRUNO BANANI Bruno Banani 061 GREEN TEA E.Arden 131 FAME Lady Gaga 123 MADE FOR WOMEN Bruno Banani 127 5th AVENUE E.Arden 076 MIRACLE Lancome 102 CHRISTINA AGUILERA C. Aguilera 039 DESIRE ME Escada 092 HYPNOSE Lancome 117 212 VIP C.Herrera 047 INTO THE BLUE Escada 101 LA VIE EST BELLE Lancome 160 212 WOMAN C.Herrera 072 BORN IN PARADISE Escada 199 LA VIE EST BELLE L`eclat Lancome 170 212 VIP ROSE C.Herrera 190 MODERN MUSE LE ROUGE Estee Lauder 109 POEME Lancome 183 GOOD GIRL C.Herrera 189 BECAUSE IT` YOU G.Armani 141 TRESOR Lancome 012 DIOR ADDICT C.Dior 010 SENSI G.Armani 175 LA NUIT TRESOR Lancome 044 MIDNIGHT POISON C.Dior 040 EMPORIO DIAMONDS G.Armani 084 ECLAT D’ARPEGE Lanvin 080 DUNE C.Dior 041 ARMANI MANIA G.Armani 001 DAISY Marc Jacobs 082 MISS DIOR CHERIE C.Dior 110 ACQUA DI GIO G.Armani 186 DECADENCE Marc Jacobs 196 MISS DIOR LE PARFUM C.Dior 111 IDOLE G.Armani 035 LOLA Marc Jacobs 093 POISON C.Dior 100 SI PASSIONE G.Armani 063 LE PARFUM Max Mara 116 DOLCE VITA C.Dior 129 SI G.Armani 172 L`EAU Mercedes 145 HYPNOTIC POISON C.Dior 135 ARMANI CODE G.Armani 124 MEXX WOMAN Mexx 159 J’ADORE C.Dior 146 ACQUA DI GIOIA G.Armani 005 JASMINE GLAM Michael Kors 188 J’ADORE IN JOY C.Dior 150 EMPORIO SHE G.Armani 171 SEXY AMBER Michael Kors 176 POISON GIRL C.Dior 053 BOLERO G.Sabatini 104 L’EAU D’ISSEY Miyake 028 DOWNTOWN C.K 090 GABRIELA SABATINI G.Sabatini 011 I LOVE Moschino -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,189,810 B1 Nerushai Et Al

USOO618981 OB1 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,189,810 B1 Nerushai et al. (45) Date of Patent: Feb. 20, 2001 (54) METHOD FOR AEROSOLSPRAYING 5,746,354 * 5/1998 Perkins ................................. 222/135 LIQUID PERFUME PRODUCTS 5,772,074 6/1998 Dial et al. ............................ 222/646 (76) Inventors: Sergei Alexeevich Nerushai, Russia, FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS 140000, Moskovskaya oblast, Ljubertsy, 2563 981 11/1985 (FR). Komsomolsky prospekt, Moscow (RU); 2586 913 3/1987 (FR). Nurakhmed Nurislamovich Latypov, 5Voikovsky proezd.d.10, kV.31, Moscow * cited by examiner 125171 (RU) Primary Examiner Andres Kashnikow Assistant Examiner Dinh Q. Nguyen (*) Notice: Under 35 U.S.C. 154(b), the term of this (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Burns, Doane, Swecker & patent shall be extended for 0 days. Mathis, L.L.P. (21) Appl. No.: 09/401,372 (57) ABSTRACT (22) Filed: Sep. 22, 1999 A method for aeroSol Spraying liquid perfume products consists of Simultaneously spraying liquid perfume products (30) Foreign Application Priority Data and/or components of liquid perfume products, having dif Oct. 7, 1998 (RU) ................................................ 98118182 ferent odors, in the form of aeroSol Streams into a region being treated. AeroSol Spraying nozzles are placed proxi (51) Int. Cl." ................................................. A62C 13/62 mate each other. The Simultaneous spraying of at least two (52) U.S. Cl. .......................... 239,306; 239/337; 239/433; components of a liquid perfume product is carried out, and 222/135; 222/402.1 during the Spraying the axes of the aeroSol Streams of the (58) Field of Search ..................................... 239/306, 337, components are positioned at an angle to each other that 239/418, 433, 543, 544; 222/137, 132, ensures interSection of the aeroSol Streams. -

2020 ANNUAL REPORT Passionate About Creativity

2020 ANNUAL REPORT Passionate about creativity Passionate about creativity THE LVMH SPIRIT Louis Vuitton and Moët Hennessy merged in 1987, creating the LVMH Group. From the outset, Bernard Arnault gave the Group a clear vision: to become the world leader in luxury, with a philosophy summed up in its motto, “Passionate about creativity”. Today, the LVMH Group comprises 75 exceptional Maisons, each of which creates products that embody unique craftsmanship, carefully preserved heritage and resolute modernity. Through their creations, the Maisons are the ambassadors of a refined, contemporary art de vivre. LVMH nurtures a family spirit underpinned by an unwavering long-term corporate vision. The Group’s vocation is to ensure the development of each of its Maisons while respecting their identity and their autonomy, by providing all the resources they need to design, produce and distribute their creations through carefully selected channels. Our Group and Maisons put heart and soul into everything they do. Our core identity is based on the fundamental values that run through our entire Group and are shared by all of us. These values drive our Maisons’ performance and ensure their longevity, while keeping them attuned to the spirit of the times and connected to society. Since its inception, the Group has made sustainable development one of its strategic priorities. Today, this policy provides a powerful response to the issues of corporate ethical responsibility in general, as well as the role a group like LVMH should play within French society and internationally. Our philosophy: Passionate about creativity THE VALUES OF A DEEPLY COMMITTED GROUP Being creative and innovative Creativity and innovation are part of LVMH’s DNA; throughout the years, they have been the keys to our Maisons’ success and the basis of their solid reputations. -

LVMH 2017 Annual Report

2017 ANNUAL REPORT Passionate about creativity Passionate about creativity W H O W E A R E A creative universe of men and women passionate about their profession and driven by the desire to innovate and achieve. A globally unrivalled group of powerfully evocative brands and great names that are synonymous with the history of luxury. A natural alliance between art and craftsmanship, dominated by creativity, virtuosity and quality. A remarkable economic success story with more than 145,000 employees worldwide and global leadership in the manufacture and distribution of luxury goods. A global vision dedicated to serving the needs of every customer. The successful marriage of cultures grounded in tradition and elegance with the most advanced product presentation, industrial organization and management techniques. A singular mix of talent, daring and thoroughness in the quest for excellence. A unique enterprise that stands out in its sector. Our philosophy: passionate about creativity LVMH VALUES INNOVATION AND CREATIVITY Because our future success will come from the desire that our new products elicit while respecting the roots of our Maisons. EXCELLENCE OF PRODUCTS AND SERVICE Because we embody what is most noble and quality-endowed in the artisan world. ENTREPRENEURSHIP Because this is the key to our ability to react and our motivation to manage our businesses as startups. 2 • 3 Selecting leather at Berluti. THE LVMH GROUP 06 Chairman’s message 12 Responsible initiatives in 2017 16 Interview with the Group Managing Director 18 Governance and Organization 20 Our Maisons and business groups 22 Performance and responsibility 24 Key fi gures and strategy 26 Talent 32 Environment 38 Responsible partnerships 40 Corporate sponsorship BUSINESS GROUP INSIGHTS 46 Wines & Spirits 56 Fashion & Leather Goods 66 Perfumes & Cosmetics 76 Watches & Jewelry 86 Selective Retailing 96 LVMH STORIES PERFORMANCE MEASURES 130 Stock market performance measures 132 Financial performance measures 134 Non-fi nancial performance measures 4 • 5 LVMH 2017 . -

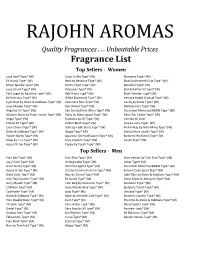

Fragrance List Print

Quality Fragrances . Unbeatable Prices Fragrance List Top Sellers - Women Love Spell Type* (W) Gucci Guilty Type* (W) Romance Type* (W) Ed Hardy Type*RAJOHN (W) Heat by Beyonce Type* (W)AROMASBlack by Kenneth Cole Type* (W) Moon Sparkle Type* (W) Jimmy Choo Type* (W) Beautiful Type* (W) Love Struck Type* (W) Pleasures Type* (W) Bombshell by VS Type* (W) Pink Sugar by Aquolina Type* (W) Reb'l Fleur Type* (W) Black Woman Type* (W) Be Delicious Type* (W) White Diamonds Type* (W) Versace Bright Crystsal Type* (W) Light Blue by Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Cashmere Mist Type* (W) Candy by Prada Type* (W) Issey Miyake Type* (W) Butt Naked Type* (W) Michael Kors Type* (W) Angel by VS Type* (W) Can Can by Paris Hilton Type* (W) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* (W) Modern Muse by Estee Lauder Type* (W) Daisy by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Miss Dior Cherie Type* (W) Angel Type* (W) Euphoria by CK Type* (W) Lick Me All Over Chanel #5 Type* (W) Amber Blush Type* (W) Viva La Juicy Type* (W) Coco Chanel Type* (W) Halle by Halle Berry Type* (W) Pink Friday by Nicki Minaj Type* (W) Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Happy Type* (W) Dot by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Flower Bomb Type* (W) Japanese Cherry Blossom Type* (W) Burberry Weekend Type* (W) Glow by J. Lo Type* (W) Juicy Couture Type* (W) Coach Type* (W) Acqua Di Gio Type* (W) Poppy by Coach Type* (W) Top Sellers - Men Polo Red Type* (M) Polo Blue Type* (M) Grey Vetiver by Tom Ford Type* (M) Jay-Z Gold Type* (M) Unforgivable Type* (M) Usher Type* (M) Gucci Guilty Type* (M) Chrome Legend Type* (M) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* -

Paco Rabanne

HERSTELLER DUFT NR PRODUKTART Aerin Amber Musk 834 PR Aventus Creed 372 P KS Bottega Veneta 819 PR Burberry The Beat 239 P Burberry London 257 P Byredo Bal D´Afrique 709 PR Cacharel Amore Amore 23 P PP PI Calvin Klein Eternity Flame 484 P Euphoria 171 PR DG Deep Euphoria 802 PR Carolina Herrera Good Girl 431 P PP 212 714 PR Cerruti Cerruti 1881 706 P Chanel Coco Mademoiselle 18 P PP PI DG BL DR KS RS No.5 21 P PI No.5 Red Limited Edition 826 PR Chance 34 P PP Chance eau Fraiche 707 PR Chance eau Tendre 322 PR Coco Noir 365 PR Gabrielle 800 PR Chloé L´Eau de Chloe 488 P Love Story 807 PR Nomade 447 P Christina Aguilera Christina Aguillera 237 P Davidoff Cool Water 419 P Dior Addict 142 PR Cherie 80 P Dune 825 PR Hypnotic Poison 173 P PI DG BL DR Jádore 10 P PP PI J´adore In Joy 806 PR Joy 445 P Midnight Poison 286 PR HERSTELLER DUFT NR PRODUKTART Dior Miss Dior Absolute Blooming 427 P Miss Dior 432 P Miss Dior 2017 801 PR Miss Dior Blooming Bouquet 810 PR Miss Dior Rose N´Roses 848 PR NEU Poison Girl 434 P DKNY Be Delicious 81 P PP PI DG BL DR Golden Delicious 443 P Dolce & Gabbana Light Blue 33 P PP PI DG BL DR The One 147 PR 3 L`Imperatrice 701 P Peony 836 PR The Only One 444 P Donna Trussardi Donna 355 PR Elisabeth Arden Green Tea 6 P Ellie Saab Le Parfum 352 PR Emporio Armani Because It´s You 817 PR Diamonds 180 P Escada Moon Sparkle 281 PR Estee Lauder Modern Muse 715 PR Ex Nihilo Fleur Narcotique 708 PR Giorgio Armani Aqua di Gio 7 P Armani Code 101 P PP Mania 177 P My Way 847 PR NEU Si 362 PR Cashmere 438 P Si Intense 804 PR Givenchy -

Action Required – Please Read in Order to Receive and Pay Your

Action Required – Please Read In order to receive and pay your invoices faster and more efficiently, LVMH P&C has joined the Transcepta Electronic Invoicing Network and asks you do the same. Please note that this initiative includes the following corporate entities: Acqua Di Parma LLC Christian Dior Inc Christian Dior Perfumes LLC Fresh Inc Guerlain Inc LVMH Fragrance Brands Canada LTD LVMH Fragrance Brands US LLC Make Up For Ever Canada LTD Make Up For Ever LLC Parfums Christian Dior Canada By sending your invoices electronically over the Transcepta procure-to-pay supplier network, you’re assured: • Immediate, secure invoice submission and guaranteed delivery to, LVMH P&C‘s Accounts Payable system, eliminating all the costs and delays of mailed invoices • Automatic invoice validation and automatic notification of incomplete invoices, which will expedite corrections and facilitate in processing and payment • Greater visibility into the payment process, tracking invoice status via confirmation emails from Transcepta or through the Transcepta supplier web portal • Enhanced trading relationship with LVMH P&C With all these advantages, it’s no surprise that 98% of suppliers in the Transcepta Community confirm that this leading e-invoicing service offers substantial improvements over traditional invoicing methods. As a LVMH P&C supplier, you pay NO FEES to participate. Plus, registration and connection with Transcepta takes only a few minutes of your time –with NO requirements to change your existing systems or invoice formats, or to engage in IT-Intensive projects. *Please do not include Social Security Numbers or Banking Information on your invoices. In joining with Transcepta, LVMH P&C considered the ease of setup and value for you LVMH P&C expects that all suppliers will enroll in the Transcepta supplier network. -

Passionate About Creativity

LVMH PASSIONATE ABOUT CREATIVITY Annual report 2007 passionate contents 02 . Chairman’s Message 14 . Review of operations 06. Financial Highlights 16. Wines & Spirits 08. Interview with Antonio Belloni: 24. Fashion & Leather Goods Many talents – a single success 32. Perfumes & Cosmetics 10. Corporate Governance 40. Watches & Jewelry 12. The LVMH Share 46. Selective Retailing 2007 LVMH about creativity 2007 52 . Sustainable development 54. Human resources Strengthening talents – Committing values 62. Corporate sponsorship to support culture, youth and humanitarian action 63. Protecting the environment 67 . Consolidated Financial Statements 01 Chairman’s Message Chairman’s The main strength of our Group, demonstrated by the consistency of the financial results, is without doubt LVMH’s unique portfolio of exceptional, globally recognised brands which are emblematic of the history and the world Bernard Arnault of luxury. an 02 Continue 2007 LVMH THE GROWTH OF LVMH HAS BEEN DRIVEN BY STRONG CONSUMER DEMAND FOR OUR PRODUCTS, AS MUCH IN EUROPE AND THE UNITED STATES AS IN EMERGING MARKETS. IN CHINA, RUSSIA AND INDIA, ALL MARKETS WITH STRONG CULTURAL TRADITIONS, NEW CLIENTS ARE LOOKING TO LVMH’S STAR BRANDS AS SYMBOLIC OF A LIFESTYLE TO WHICH THEY ASPIRE ENTHU- SIASTICALLY. THANKS TO ITS UNIQUE PORTFOLIO OF ICONIC BRANDS, THE TALENT OF ITS TEAMS AND THE GLOBAL REACH OF ITS BUSINESS, LVMH IS IN AN EXCELLENT POSITION TO GAIN MARKET SHARE AND TO CONTINUE ITS LEADERSHIP IN THE LUXURY GOODS MARKET IN 2008 AND BEYOND. By accentuating growth in both traditional and Louis Vuitton trunks have been sold in Australia to invest in their development. Over the years emerging markets over the course of 2007, since the end of the 19th century. -

Journal of Intellectual Property and Entertainment Law

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND ENTERTAINMENT LAW VOLUME 5 FALL 2015 NUMBER 1 LOST AND FOUND: INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY OF THE FRAGRANCE INDUSTRY; FROM TRADE SECRET TO TRADE DRESS CHARLES CRONIN* INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................257 I. THE FRAGRANCE INDUSTRY AND THE CHALLENGE OF REVERSE ENGINEERING ................................................................................................263 A. Regulation of Reverse Engineering in the United States and the European Union .....................................................................................263 B. Challenges to the Fragrance Industry’s Traditional Reliance on Trade Secrets ..........................................................................................267 C. The Impact of Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Technologies on the Fragrance Industry ...............................................270 II. PATENT AND COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR FRAGRANCES ............................273 A. Patent ......................................................................................................273 B. Copyright ................................................................................................276 C. France and the Netherlands: Odor in the Courts ..................................280 III. FRAGRANCE AND TRADEMARK PROTECTION ................................................283 A. The Expanding Scope of Trademark Protection ....................................283