CHALLENGE 2015: TOWARDS SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT THAT LEAVES NO ONE BEHIND Challenge 2015: Towards Sustainable Development That Leaves No One Behind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Late Registrations and Corrections to Greene County Birth Records

Index for Late Registrations and Corrections to Birth Records held at the Greene County Records Center and Archives The late registrations and corrections to Greene County birth records currently held at the Greene County Records Center and Archives were recorded between 1940 and 1991, and include births as early as 1862 and as late as 1989. These records represent the effort of county government to correct the problem of births that had either not been recorded or were not recorded correctly. Often times the applicant needed proof of birth to obtain employment, join the military, or draw on social security benefits. An index of the currently available microfilmed records was prepared in 1989, and some years later, a supplemental index of additional records held by Greene County was prepared. In 2011, several boxes of Probate Court documents containing original applications and backup evidence in support of the late registrations and corrections to the birth records were sorted and processed for archival storage. This new index includes and integrates all the bound and unbound volumes of late registrations and corrections of birth records, and the boxes of additional documents held in the Greene County Archives. The index allows researchers to view a list arranged in alphabetical order by the applicant’s last name. It shows where the official record is (volume and page number) and if there is backup evidence on file (box and file number). A separate listing is arranged alphabetically by mother’s maiden name so that researchers can locate relatives of female relations. Following are listed some of the reasons why researchers should look at the Late Registrations and Corrections to Birth Records: 1. -

The Least Developed Country (LDC) Category at 40 Djalita Fialho

Aiming high, falling short: the Least Developed Country (LDC) category at 40 Djalita Fialho ISS - Institute of Social Studies Abstract Why have 94% of LDCs not escaped poverty during the last four decades? This paper analyses the motivation behind the UN decision to establish the LDC category in 1971. The reviewed literature highlights the conflicting interests of the actors involved. It provides a historical account of the creation of the category and an international political economy analysis of that process. Based on this literature, I argue that the initial LDC identification process - which set a precedent for future LDC categorizations - was manipulated in order to generate a reduced list of small and economically and politically insignificant countries. Contrary to the LDC official narrative, this list served the interests of both donors (by undermining the UN’s implicit effort to normalize international assistance) and other non-LDC developing countries (disturbed by the creation of a positive discrimination within the group, favoring the most disadvantaged among them). As a result of this manipulation, considerably less development-promoting efforts have been demanded from donors, which has, in turn, not significantly distressed the interests of other non-LDC developing countries. Keywords: LDCs, aid, trade, preferential treatment, graduation JEL Classification: N20, O19 1. Introduction In May 2011 the international community, under the auspices of the UN, gathered for the fourth time in 40 years to assess progresses made by the least developed country (LDC) group. The conference took place in Istanbul, under the grim shadow of a stagnant and non-evolving category, whose membership has not declined for most of its lifespan. -

FEATURE PRESENTATION • G1 PRIX DE DIANE Contest

Visit the WIN WILLY DQ’d from TDN Website: GIII Razorback H. win www.thoroughbreddailynews.com P4 THURSDAY, JUNE 10, 2010 For information about TDN, call 732-747-8060. RACHEL ALEXANDRA TO FLEUR DE LIS Co-owner Jess Jackson announced yesterday that Horse of the Year Rachel Alexandra (Medaglia d=Oro) will make her next start in the GII Fleur de Lis S. Saturday at Churchill Downs. AAs long as she continues to progress, Peslier on Makfi... we intend to race her with the expecta- Olivier Peslier has been booked to partner the tion that she will obtain her fitness level G1 2000 Guineas winner Makfi (GB) (Dubawi {Ire}) in of last year, Jackson said in a state- @ Tuesday=s G1 St James=s Palace S., for which 15 were ment. AOur ultimate goal and hope is to declared yesterday. With Christophe-Patrice Lemaire enter the Breeders= Cup in November.@ retained by His Highness The Aga Sarah K Andrew photo Perfect in eight starts with three Grade I Khan for J “TDN Rising Star” wins against the boys during her cham- J Siyouni (Fr) (Pivotal {GB}), the pionship campaign, four-year-old Rachel Alexandra has Newmarket Classic winner=s own- been second in both starts this season, the Mar. 13 ers Mathieu Offenstadt, Alain New Orleans Ladies S. and the Apr. 30 GII La Troienne Louis-Dreyfus, Sylvain Fargeon S. The bay has been first or second in 15 of 16 appear- and Mikel Delzangles, who also ances, earning $3,074,050. Field, p3 trains the colt, have been forced to seek a new rider in the mile FEATURE PRESENTATION • G1 PRIX DE DIANE contest. -

Academic Forum 2016

RIS MINISTRY OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS Research & Information Systems Government of India for Developing Countries Academic Forum 2016 SEPTEMBER 19-22 l GOA, INDIA SEPTEMBER 19-22 l GOA, INDIA Designed by: Anil Ahuja ([email protected]) Layouts: Puja Ahuja ([email protected]) Typesetting: Syed Salahuddin Academic Forum 2016 Contents Agenda 03 Speakers 17 Useful Information 77 The BRICS Academic Forum is a Track 2 platform for Academics from the five countries to deliberate on issues of crucial impor- tance to BRICS and come up with ideas and recommendations. Such Academic Fora have been held before every BRICS Summit so far. It is a matter of pride for this platform that in the past many of its ideas have been reflected in the final Summit documents. The Forum usually invites 10-12 scholars from each member na- tion to speak on themes of importance. In addition, a large num- ber of scholars from all countries participate in the deliberations. ORGANISING PARTNERS MINISTRY OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS Government of India 1 programme SEPTEMBER 19-22 l GOA, INDIA Agenda: Programme Schedule DAY - ZERO Monday, September 19, 2016 18:00 – 18:10 Welcome and Opening Remarks: Sunjoy Joshi Director, Observer Research Foundation, India 18:10 – 18:30 Keynote Address by Shri. Laxmikant Yashwant Parsekar, Honorable Chief Minister of Goa 18:30 – 18:40 Closing Remarks: Sachin Chaturvedi, Director General, Research and Information Systems for Developing Countries (RIS), India Master of Ceremony—Samir Saran, Vice President, Observer Research Foundation, India 18:45 – 20:15 Inaugural Session: Emerging Geo-Political Order: Challenges and Opportunities for BRICS (Aguada Ballroom) This session will discuss the future of the multilateral and multi-layered system as established since the 20th century. -

Central Reformed Church Sixth Sunday of Easter May 17, 2020

Central Reformed Church Sixth Sunday of Easter May 17, 2020 REFLECTION “The following reasons may be given why children ought to love Jesus Christ above things in the world: He is more lovely in Himself. He is one that is greater and higher than all the kings of the earth, has more honor and majesty than they, and yet He is innately good and full of mercy and love. There is no love so great and so wonderful as that which is in the heart of Christ. He is one that delights in mercy. He is ready to pity those that are in suffering and sorrowful circumstances as one that delights in the happiness of His crea- tures. The love and grace that Christ has manifested does as much exceed all that which is in this world as the sun is brighter than a candle. Parents are often full of kindness towards their children, but that is no kindness like Jesus Christ’s…. There is more good to be enjoyed in Him than in everything or all things in this world. He is not only an amiable, but an all-sufficient good. There is enough in Him to answer all our wants and satisfy all our desires.” —Jonathan Edwards, “Children Ought to Love the Lord Jesus Christ Above All,” Sermons and Dis- courses: 1739-1742, in The Works of Jonathan Edwards, vol. 22, ed. Harry S. Stout (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 171-172. ORDER OF WORSHIP SIXTH SUNDAY OF EASTER MAY 17, 2020 9:30 am (We invite you to quiet your homes as you prepare for worship.) ____________________________________________________________ GATHERING IN LOVE Prelude “Moonlight Sonata, 1st Movement, Op. -

NATIONAL Tictoricti SHOW ISSUE TOWNSHEND MORGAN-HOLSTEIN FARM BOLTON, MASS

35 SEPTEMBER, 1959 (it- MORGAN HORSE NATIONAL Tictoricti SHOW ISSUE TOWNSHEND MORGAN-HOLSTEIN FARM BOLTON, MASS. Our consignment to this year's Green Meads Morgan Weanling Sale — TOWNSHEND VIGILANTE Sire: Orcland Vigildon Dam: Windcrest Debutante Talk about New England's Red Flannel Hash this is New England's Blue Ribbon Hash. This colt is a mixture of all the best champion New England Blood. His grandsires are the famous Cornwallis, Upwey Ben Don, and Ulendon. His granddam is none other than Vigilda Burkland. His own sire ORCLAND VIGILDON was New England Champion, East- ern States Champion, Pennsylvania National Champion and Reserve Champion Harness and Saddle Horse at National Morgan Shows. He is a full brother to Orcland Leader and Vigilda Jane. His own dam, WINDCREST DEBUTANTE, winner of several champion- ships for us in 1957, is a full sister to Brown Pepper and Donnie Mac. Here is a champion for you if you bid last on this good colt! ORCLAND FARMS "Where Champions Are Born" — ULENDON BLOOD TELLS — We wish to congratulate all his offspring that placed at the 1959 National Morgan Horse Show and list the winners: SONS and DAUGHTERS: VIGILDA JANE—second year in succession winner of Mare and Foal ORCLAND LEADER—Stallion Parade HAVOLYN DANCER—Geldings over 4 years and Reserve Champion Gelding ORCLAND QUEEN BESS—Walk-Trot ridden by Linda Kean GRANDCHILDREN: MADALIN—Mares and Geldings in Harness, Ladies' Mares and Geldings in Harness, Championship Harness Stake PROMENADE—Junior Saddle Stake HILLCREST LEADER—Junior Harness Stake VIGILMARCH-2 year old Stallions in Harness BOLD VENTURE—Stallion Foals GREEN MT. -

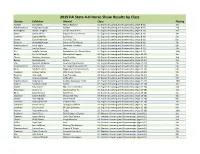

2019 State Horse Show Results by Class and County

2019 PA State 4-H Horse Show Results by Class County Exhibitor Animal Class Placing Fayette Joely Miller Million Reasons 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 1st Westmoreland Abby McCullough Harllee 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 2nd Huntingdon Hannah Feagley Secure Your Assets 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 3rd Potter Savannah Kio Peppers Precious Penny 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 4th Crawford Sophie Wehrle Zip O Cool 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 5th Snyder Gavyn Heimbach I Can Pass Too 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 6th Dauphin Charlotte Duncan Dancin In The Weeds 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 7th Westmoreland Anna Zeglin Attractive Invitation 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 8th Warren Emelyn Moore skip 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 9th Erie Isabella Cannata Romandaros Sirs Painted Bear 01: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 8-11) 10th Berks Caitlin Diffendal Miracles Do Happen 02: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 12-14) 1st Clinton Madelyn Hendricks Invy The Ride 02: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 12-14) 2nd Beaver Charity Tellish Kuhlua 02: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 12-14) 3rd Erie Madison Anderson One Smoking Maverick 02: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 12-14) 4th Westmoreland Kaitlynn Lebo I've Tango'd My Socks Off 02: English Grooming and Showmanship, (Ages 12-14) 5th Berks Elizabeth Jones Magic Sweet Princes Beauty 02: -

Human Rights and Disability

Human Rights and Disability The current use and future potential of United Nations human rights instruments in the context of disability Gerard Quinn and Theresia Degener with Anna Bruce, Christine Burke, Dr. Joshua Castellino, Padraic Kenna, Dr. Ursula Kilkelly, Shivaun Quinlivan United Nations New York and Geneva, 2002 ii ________________________________________________________________________ Contents NOTE Symbols of United Nations document are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner on Human Rights. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Nor does the term “national institution” in any way imply conformity with the “Principles relating to the status of national institutions” (General Assembly resolution 48/134 of 20 December 1993, annex). HR/PUB/02/1 Copyright © United Nations 2002 All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be freely quoted or reproduced or stored in a retrieval system for non-commercial purposes, provided that credit is given and a copy of the publication containing the reprinted material is sent to the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Palais des Nations, CH- 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form without the prior permission of the copyright owner if the purpose relates to profit-making ventures. -

GRASS and CACTUS Barn a Hip No. 21

Consigned by Hidden Springs Ranch, Agent for Jerry Engelauf Barn GRASS AND CACTUS Hip No. A 21 Mr. Prospector Miswaki ............................ Hopespringseternal Cactus Creole .................. The Minstrel GRASS AND CACTUS Wonderous Minstrel ........ Chestnut Colt; Passing Look March 1, 2014 Pulpit Lucky Pulpit ...................... Lucky Soph Above the Grass ................ (2009) Shadeed Swill .................................. Gay Chiffon By CACTUS CREOLE (1996). Sire of 13 crops of racing age, 71 foals, 37 starters, 15 winners of 37 races and earning $648,417, including Lim - ited Creole (5 wins, $168,410, 3rd Palos Verdes H.-G2), Sassy Minstrel (3rd Thoroughbred Derby), Cactus Flyer ($100,746), Limited Will ($42,- 384), No Limit Poker (4 wins, $41,671), Ourfavoriteone ($36,570), Cac - tus Breeze ($33,834), Little Bit Cactus ($31,002), Cactus Lighting ($28,460), Sincy's Wonder ($22,751). Son of stakes winner Miswaki. 1st dam ABOVE THE GRASS, by Lucky Pulpit. Placed at 3. This is her first foal. 2nd dam SWILL, by Shadeed. Winner at 3 and 4, $27,670. Dam of 4 winners, including-- PHEIFFER (f. by Lyphaness). 8 wins, 3 to 6, $232,270, Charles H. Russell H., Richmond H., Vacaville H., 2nd Autumn Leaves H., Vacaville H., Elie Destruel H., 3rd Camilla Urso H., Orinda H., Charles H. Russell H., Luther Burbank H. THRILL AFTER DARK (f. by Lyphaness). 12 wins, 2 to 8, $180,992, Idaho Cup Distaff Derby-R, Lady's Secret H., Idaho Cup Distaff Maturity-R, Winning Colors H.-R, Winning Colors S.-R, ITA Sophomore Distaff S.-R, 2nd Ginger Welch S., 3rd Lady's Secret H., Idaho Cup Distaff Maturity-R. -

Division of Student Affairs

Division of Student Affairs Annual Report 2005-2006 May 2007 Table of Contents Section I: Organization & Purpose .............................................................................. 4 Mission Statement and Values ..................................................................................... 5 Unit and Directors List .................................................................................................. 6 Organizational Chart ..................................................................................................... 7 Publications by VPSA Office ......................................................................................... 9 Section II: Unit Reports ............................................................................................... 11 American Indian Student Services ............................................................................. 12 Campus Recreation ................................................................................................... 24 Career Services ......................................................................................................... 45 Curry Health Center ................................................................................................... 81 Disability Services for Students ................................................................................. 95 Enrollment Services ................................................................................................. 117 Foreign Student & Scholar Services -

2017 State Horse Show Results by Class

2017 PA 4-H Horse Show Results by Class Place Exhibitor Town Horse County English Grooming & Showmanship, 8-11 1 Hannah FeagleyPetersburg Secure Your Assets Huntingdon 2 Abby McCulloughManor Shieks Special Te Westmoreland 3 Adyson FranzMoon Township Echo Beaver 4 Abby SpinoGreensburg One Hot Capachino Westmoreland 5 Coveyn BearBenton Deon Columbia 6 Emma FuchsVolant Art I A Lark Lawrence 7 Ashlee HackPalmyra Hunting with Faith Dauphin 8 Yanina OteroPalmyra Hopeful Hobby Dauphin 9 Julia DiNapoliWalnutport Penny in Your Pocket Northampton 10 Alycia SzyskoWarrington Bullseye Bucks English Grooming & Showmanship, 12-14 1 Evalee BinnsBrownsville So Hot Im Krymsun Washington 2 Brook BrehmWindber Envious Version Somerset 3 Caiden BathkeEllwood City Knights Miss Swiss Lawrence 4 Madelyn HendricksJersey Shore Invy The Ride Clinton 5 Sarah FisherGeorgetown Pardons Sonny Beaver 6 Emilee HeverlyMill Hall Lil Bonanza Leaguer Clinton 7 Malaina MacostaDaisytown Jutti Westmoreland 8 Nadia SlishHonesdale Wildfire Wayne 9 Jenna TysonPottstown My Tea Impact Berks 10 Rylan FaganZion Grove CSH Porcelain Doll Columbia English Grooming & Showmanship, 15-18 1 Alexus HartmanMcClure Just Another Detail Mifflin 2 Laura LanagerFrenchville Zippos Sweet C Clearfield 3 Katharine HendricksJersey Shore A Good Premonition Clinton 4 Madison HeilveilLansdale Backwoods Boy Bucks 5 Emily MannaHarrisburg Sr Lil Bit of Love Dauphin 6 Cambrie ShortGreensburg Mostly Cloudy Skies Westmoreland 7 Katherine BowserEllwood City Sonnys Bedazzled Lawrence 8 Kyrsten KowalczykFlinton Fire -

Baby Girl Names Registered in 2012

Page 1 of 49 Baby Girl Names Registered in 2012 # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names 1 Aadhira 1 Abbey-Gail 1 Adaeze 3 Aadhya 1 Abbi 2 Adah 1 Aadya 1 Abbie 1 Adaira 1 Aahliah 11 Abbigail 1 Adaisa 1 Aahna 1 Abbigaile 1 Adalayde 1 Aaira 2 Abbigale 3 Adalee 1 Aaiza 1 Abbigayle 1 Adaleigh 1 Aalaa 1 Abbilene 2 Adalia 1 Aaleah 1 Abbrianna 1 Adalie 1 Aaleya 20 Abby 1 Adalina 1 Aalia 8 Abbygail 1 Adalind 1 Aaliah 1 Abbygail-Claire 2 Adaline 33 Aaliyah 1 Abbygaile 8 Adalyn 1 Aaliyah-Faith 3 Abbygale 1 Adalyne 1 Aaliyah-noor 1 Abbygayle 10 Adalynn 1 Aamina 1 Abby-lynn 1 Adanaya 1 Aaminah 1 Abebaye 2 Adara 1 Aaneya 2 Abeeha 1 Adau 1 Aangi 1 Abeer 2 Adaya 1 Aaniya 2 Abeera 1 Adayah 2 Aanya 1 Abegail 1 Addaline 3 Aaralyn 1 Abella 1 Addalyn 2 Aaria 1 Abem 1 Addalynn 3 Aarna 1 Abeni 1 Addeline 1 Aarohi 2 Abheri 1 Addelynn 1 Aarolyn 1 Abida 3 Addie 1 Aarvi 1 Abidaille 1 Addie-Mae 2 Aarya 1 Abigael 3 Addilyn 1 Aaryana 159 Abigail 2 Addilynn 1 Aasha 1 Abigaile 1 Addi-Lynne 2 Aashi 3 Abigale 78 Addison 1 Aashka 1 Abigayl 13 Addisyn 1 Aashna 2 Abigayle 1 Addley 1 Aasiyah 1 Abijot 1 Addy 1 Aauriah 1 Abilleh 9 Addyson 1 Aavya 1 Abinoor 1 Adedamisola 1 Aayah 2 Abrianna 1 Adeena 1 Aayana 2 Abrielle 1 Adela 1 Aayat 2 Abuk 1 Adelade 2 Aayla 1 Abyan 1 Adelae 1 Aayushi 3 Abygail 14 Adelaide 1 Ababya 2 Abygale 1 Adelaide-Lucille 1 Abagail 1 Acacia 2 Adelaine 1 Abagayle 1 Acasia 17 Adele 1 Abaigael 2 Acelyn 1 Adeleah 1 Abba 1 Achan 1 Adelee 1 Abbagail 2 Achol 1 Adeleigh 1 Abbegail 1 Achsa 1 Adeleine 12 Abbey 11 Ada 2 Adelia Page 2 of 49 Baby Girl