German Airline Regulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Passengers at Frankfurt Airport

Passengers at Frankfurt Airport Top 3 Destinations by world region Frankfurt Airport (FRA) is Germany’s global gateway and one of the world’s largest aviation Age Group hubs. In 2019, over 70 million passengers departed, arrived or connected to another flight via under 30 years 16 % Berlin TXL London LHR FRA. Who are these passengers passing through the terminals or seated on the planes at FRA? 30 – 39 years 26 % Hamburg HAM Palma PMI Where do they come from and where are they flying to? To find this out, Fraport (the owner and Europe* Germany operator of Frankfurt Airport) has been continuously conducting passenger surveys since 1991. Munich MUC Vienna VIE 40 – 49 years 31 % Each month, some 2,400 passengers on average are surveyed on topics such as age, residency, Johannesburg JNB Dubai DXB or reason for flying. Did you know, for example, that passengers stay at FRA for an average of 50 – 59 years 20 % Hurghada HRG Shanghai PVG 2 hours and 19 minutes per journey? over 60 years 7 % Asia Africa Cairo CAI Seoul ICN New York JFK São Paulo GRU Country of origin/residence Toronto YYZ Rio de Janeiro GIG Other countries 22.3 % Chicago ORD Cancún CUN South America North America *excluding Germany 54.6 % 45.4 % Germany Average number of flights by business and leisure U.S. 9.8 % passengers (per year) U.K. 3.9 % Austria 3.6 % Italy 3.3 % 5.3 France 2.9 % Sweden 1.8 % 11.1 flights Spain 2.6 % Canada 2.2 % flights 2.2 Reason for flying Reason for flying Switzerland 2.2 % flights All travelers 35 % 65 % Business Leisure Mode of ground access to FRA Leisure travelers Business travelers Private car 40 % Passenger split Taxi 20 % S-Bahn metropolitan train 14 % ICE/ 11 % 39 % 61 % Long-distance train Female Male Private Transfer 54 % 46 % Origin & shuttle service 5 % passengers Destination Rental car 4 % passengers Others 3 % Survey methodology: Ongoing individual interviews with passengers i (from a representative sample of passengers, selected at random). -

Airport Research and Innovation Facility Hamburg (ARIF) Airport Research and Innovation Facility Hamburg (ARIF)

Airport Research and Innovation Facility Hamburg (ARIF) Airport Research and Innovation Facility Hamburg (ARIF) Parallel to the installation of an operational A-SMGCS (Advanced Surface Movement Guidance and Control System) at Hamburg Airport, three partners agreed on the cooperation in installing and operating a unique field test platform for research and development in the field of air traffic manage- ment and airport operation. Trials to identify and evaluate improved ground processes The cooperation of DFS Deutsche Flugsicherung GmbH, Ham- burg Airport and the German Aerospace Center (DLR) enables a large variety of opportunities for both operational stakehold- ers and research/development. In 2006, the partners set up the Airport Research and Innovation Facility Hamburg (ARIF) as an operational environment. Thus, existing research infrastruc- tures such as apron, tower or airport control centre simulators could be extended with important operational input. The ARIF is a unique platform for the development, testing, evaluation and validation of future support systems in an operational en- vironment, aiming at midsize airports. Thus, ARIF provides essential advantages, such as: - Use of real-time data during development phases - Short cycles between implementation of innovative ideas and operators’ feedback - Direct evaluation of existing system components - (Pre-) testing of new concepts and future technology without operational limitations - Optimal infrastructure for shadow mode trials Research Areas Besides focusing on higher levels of A-SMGCS (e.g. planning and guidance), the ARIF at Hamburg Airport is also designed to allow research in the context of Total Airport Management (TAM) and Performance Based Airport Management (PBAM). All partners have identified the need for the development and implementation of an integrated airport management with a common set of operational data. -

Zum Gutachen

FOLGEUNTERSUCHUNG: HANNOVER AIRPORT EIN ZENTRALER WIRTSCHAFTS- UND STANDORT- FAKTOR FÜR DIE REGION Untersuchung im Auftrag der Flughafen Hannover-Langenhagen GmbH Prof. Dr. Lothar Hübl Dr. Karin Janssen Dipl.-Ök. Bernd Wegener Hannover, aktualisiert im Mai 2019 ANSCHRIFT DER VERFASSER: __________________________________________________________ ISP Eduard Pestel Institut für Systemforschung e.V. Gretchenstr. 7, 30161 Hannover, [email protected] INHALT Seite VORBEMERKUNG WICHTIGE ERGEBNISSE IM ÜBERBLICK I-XIII 1. TENDENZEN UND SPANNUNGSFELDER IM LUFTVERKEHR 1 2. TECHNISCHE AUSSTATTUNG UND VERKEHRSENTWICKLUNG: BESTANDSAUFNAHME 13 2.1 Ausstattung 13 2.2 Direktverbindungen und Fluggastaufkommen 21 2.3 Luftfrachtaufkommen 33 2.4 Luftpostaufkommen 35 2.5 Flugzeugbewegungen 36 3. BEVÖLKERUNGS- UND WIRTSCHAFTSSTRUKTUR DER FLUGHAFENREGION HANNOVER 38 3.1 Ermittlung des Einzugsgebietes 38 3.2 Bevölkerungsstruktur und Bevölkerungsdynamik in der Flughafenregion Hannover 42 3.3 Wirtschaftliche Bedeutung und Wirtschaftsstruktur der Flughafenregion Hannover 45 4. FLUGHAFENREGION IM INTERNATIONALEN WETTBEWERB 55 4.1 Art und Form der außenwirtschaftlichen Aktivitäten niedersächsischer Unternehmen 59 4.2 Warenhandel mit dem Ausland 63 4.3 Dienstleistungsverkehr mit dem Ausland 72 4.4 Direktinvestitionsverflechtungen mit dem Ausland 79 5. HANNOVER AIRPORT ALS STANDORTFAKTOR 85 5.1 Grundsätzliche Überlegungen zur Standortgunst 85 5.2 Wechselwirkungen mit weiteren Standortfaktoren 86 5.3 Relevanz von Standortfaktoren für Unternehmen 88 INHALT Seite 6. -

2Nd Joint Meeting of US and European DIERS User Group

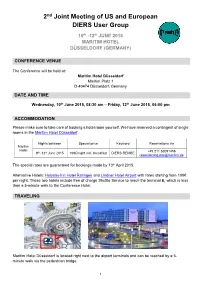

2nd Joint Meeting of US and European DIERS User Group 10th -12th JUNE 2015 MARITIM HOTEL DÜSSELDORF (GERMANY) CONFERENCE VENUE The Conference will be held at: Maritim Hotel Düsseldorf Maritim Platz 1 D-40474 Düsseldorf, Germany DATE AND TIME Wednesday, 10th June 2015, 08:30 am – Friday, 12th June 2015, 06:00 pm ACCOMMODATION Please make sure to take care of booking a hotel room yourself. We have reserved a contingent of single rooms in the Maritim Hotel Düsseldorf Nights between Special price Keyword Reservations via Maritim Hotel +49 211 52091456 9th -12th June 2015 169€/night incl. breakfast DIERS-REMBE [email protected] The special rates are guaranteed for bookings made by 13th April 2015. Alternative Hotels: Holyday-Inn Hotel Ratingen and Lindner Hotel Airport with fares starting from 100€ per night. These two hotels include free of charge Shuttle Service to reach the terminal B, which is less than a 5-minute walk to the Conference Hotel. TRAVELING Maritim Hotel Düsseldorf is located right next to the airport terminals and can be reached by a 5- minute walk via the pedestrian bridge. 1 By plane: There are several airlines which fly directly to Düsseldorf International Airport. *Please note that some Lufthansa flights flying to Frankfurt Airport, with connection flight to Düsseldorf Airport operate by train (DeutscheBahn) between both airports and not by plane. It is desirable to book a direct flight to Düsseldorf Airport. By train: Düsseldorf International Airport has two railway stations: (http://www.dus.com/dus_en/bahn/) • “Düsseldorf Airport Station” (Düsseldorf Flughafen) is located at the eastern end of the airport site. -

Arriving at Koelnmesse

Arriving at Koelnmesse Arriving by public transportation Arriving by air Underground Lines 1 and 9: “Bahnhof Deutz” station We generally advise our guests to travel by rail from The South Entrance is approx. three minutes walk from the Cologne/Bonn, Düsseldorf and Frankfurt airports to platform at this station. Cologne. Alternatively you can take a taxi or arrange a hire car. Underground Lines 3 and 4: “Koelnmesse” station Lines 3 and 4 stop directly at the East Entrance. Cologne-Bonn Airport (Distance Koelnmesse: approx. 16 km) Cologne-Bonn Airport has its own station called “Köln/Bonn Arriving by the Deutsche Bahn (German Railways) Flughafen”. In the airport, follow the signs to the train platforms. Cologne “Messe/Deutz” train station Here you can either take the No. 13 suburban railway (in the (Distance Koelnmesse: approx. 0.3 km) direction of Horrem) or the Regional Express (in the direction of We recommend you to arrive at Cologne “Messe/Deutz” train Mönchengladbach) to the station “Köln Messe/Deutz”, located station. From there the South Entrance is approx. three minutes adjacent to the exhibition centre. The trip from the airport takes walk away. about 12 minutes. (Further information “Arriving by the Deutsche Bahn/German Railways”) Cologne Main Station (Hauptbahnhof) (Distance Koelnmesse: approx. 1.5 km) Düsseldorf Airport If your train arrives at Cologne Main Station, there are four ways (Distance Koelnmesse: approx. 65 km) to get from there to Koelnmesse: Düsseldorf airport has its own station called “Flughafen Düsseldorf”. After leaving customs, follow the signs in the airport 1. By foot over the “Hohenzollern” bridge to the Sky Train. -

Public Infrastructure Project Planning in Germany: the Case of the BER Airport in Berlin-Brandenburg

Large Infrastructure Projects in Germany Between Ambition and Realities Working Paper 3 Public Infrastructure Project Planning in Germany: The Case of the BER Airport in Berlin-Brandenburg Registration I will attend: By Jobst Fiedler and Alexander Wendler This working paper is part of the research project by the Hertie School of Governance Name on Large Infrastructure Projects in Germany – Between Ambition and Realities. For further information:Position www.hertie-school.org/infrastructure The study was made possible by theInstitution friendly support of the Karl Schlecht Foundation Email Hertie School of Governance | May 2015 Accompanied by Contents 1. Introduction………………………………………………………….... 1 1.1 High-profile failure in large infrastructure projects…………………... 1 1.2 Research Question and Limitations………………………………….. 3 1.3 Hypothesis…………………………………………………………….... 4 1.4 Methods of Inquiry and Sources…………………………………….... 6 2. Megaprojects and their Inherent Problems………………………. 8 2.1 Large-scale Infrastructure Projects – an Introduction………………. 8 2.2 Empirical Performance of Large-scale Infrastructure Projects…….. 8 2.3 Drivers of Project Performance……………………………………….. 9 2.3.1 National Research Council (US Department of Energy) …………... 9 2.3.2 Miller and Lessard (IMEC Study) …………………………………….. 10 2.3.3 Flyvbjerg et al…………………………………………………………... 11 2.3.4 Mott MacDonald………………………………………………………... 14 2.3.5 Institute for Government / 2012 London Olympics………………….. 15 2.3.6 Eggers and O’Leary (If We Can Put A Man On The Moon) ………… 17 2.4 Analytical Framework for Review of BER Project…………………… 18 3. The BER Project………………………………………………………. 20 3.1 Background: The Long Road Towards a New Airport in Berlin…….. 20 3.2 BER Governance and Project Set-Up………………………………... 21 3.2.1 Against better knowledge: failure to appoint a general contractor and consequences for risk allocation………………………………… 21 3.2.2 Project Supervision and Control: deficiencies in structure and expertise levels………………………………………………………… 26 3.2.3 Financing and the Role of Banks…………………………………….. -

ICAO State Action Plan on Emissions Reduction - Germany

ICAO State Action Plan on Emissions Reduction - Germany - Page 1 out of 41 Impressum Federal Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Development Directorate General for Civil Aviation Robert-Schuman Platz 1 53175 Bonn Principal Contact Mr. Jan Bode Tel +49 228 99-300-4923 Fax +49 228 99-300-807-4923 E-Mail [email protected] Page 2 out of 41 INTRODUCTION 4 Current state of aviation in the Federal Republic of Germany 6 Structure of the aviation sector and its contribution to CO2 emissions 6 General Transport Data 8 Geographical characteristics 17 SECTION 1- Supra-national actions, including those led by the EU 17 1. Aircraft related Technology Development 17 2. Alternative Fuels 20 3. Improved Air Traffic Management and Infrastructure Use 23 4. Economic / market-based measures 26 5. Support to voluntary actions: ACI Airport Carbon Accreditation 28 SECTION 2- National Measures in Federal Republic of Germany 30 1. Aircraft related Technology Development 30 2. Alternative Fuels 34 3. Improved Air Traffic Management and Infrastructure Use 35 4. Economic / market-based measures 41 5. Support to voluntary actions: ACI Airport Carbon Accreditation 41 Annex 41 Page 3 out of 41 INTRODUCTION a) The Federal Republic of Germany is a Member of European Union and of the European Civil Aviation Conference (ECAC). ECAC is an intergovernmental organisation covering the widest grouping of Member States1 of any European organisation dealing with civil aviation. It is currently composed of 44 Member States, and was created in 1955. b) The ECAC States share the view that environmental concerns represent a potential constraint on the future development of the international aviation sector, and together they fully support ICAO’s ongoing efforts to address the full range of these concerns, including the key strategic challenge posed by climate change, for the sustainable development of international air transport. -

Managing Passenger Handling at Airport Terminals Individual-Based Approach for Modeling the Stochastic Passenger Behavior

Ninth USA/Europe Air Traffic Management Research and Development Seminar (ATM2011) Managing Passenger Handling at Airport Terminals Individual-based Approach for Modeling the Stochastic Passenger Behavior Michael Schultz and Hartmut Fricke Chair of Air Transport Technology and Logistics Technische Universität Dresden 01062 Dresden, Germany {schultz, fricke}@ifl.tu-dresden.de Abstract—An efficient handling of passengers is essential for actions. Therefore, appropriate agent models have to be devel- reliable terminal processes. Since the entire progress of terminal oped and calibrated with empirical data. A calibration is man- handling depends on the individual behavior of the passengers, a datory to legitimate the application of the individual model valid and calibrated agent-based model allows for a detailed characteristics and allows for developing efficient system de- evaluation of system performance and for identifying optimiza- sign. tion capabilities. Our model is based on a stochastic approach for passenger movements including the capability of individual tacti- In turnaround procedures the behavior of individual pas- cal decision making and route choice, and on stochastic model of sengers is crucial for the handling efficiency, since both de- handling processes. Each component of the model was calibrated boarding and boarding are part of the critical path. Datasets with a comprehensive, scientifically reliable empirical data set; a from Airbus A380 ground handling at Emirates indicate a sig- virtual terminal environment was developed and real airport nificant level of impact of passenger handling at hub structures, conditions were evaluated. Our detailed stochastic modeling caused by a high transfer passenger volume [1]. The hub struc- approach points out the need for a significant change of the ture is a directly coupled transport system, which not only common flow-oriented design methods to illuminate the still possess intermodal traffic change (landside arrivals) but as well undiscovered terminal black box. -

American Airlines in Europe American Operates up to 434 Weekly Flights Between Europe and the United States

American Airlines in Europe American operates up to 434 weekly flights between Europe and the United States. Overview • From its hubs in the United States, American offers connections to nearly 350 cities in over 50 countries worldwide, with approximately 6,700 daily flights. • American now offers up to 62 daily flights between Europe and Chicago O’Hare (ORD), Charlotte (CLT), Dallas Fort Worth (DFW), Los Angeles (LAX), Miami (MIA), New York (JFK), Philadelphia (PHL) and Raleigh/ Durham (RDU). • American has dedicated sales offices in Amsterdam, Dublin, Frankfurt, London, Madrid, Milan, Paris, Rome and Zürich. • American has a dedicated reservations center in Liverpool, England, handling European reservations queries, AAdvantage customers, special assistance and ticketing. • American has dedicated Admirals Club lounges in London Heathrow, Terminal 3 (LHR) and Paris Charles de Gaulle, Terminal 2A (CDG American also has a Flagship First Class lounge and an Arrivals Lounge in Heathrow Terminal 3, the only one of its kind in the airline’s network. • Beginning May 6th, 2017, American will launch new seasonal services from Rome Fiumicino Airport (FCO) and Amsterdam Schiphol Airport (AMS) to Dallas/ Fort Worth and from Barcelona El Prat Airport (BCN) to Chicago O’Hare. Leadership in Europe • Olympia Colasante, Managing Director – London Heathrow • Andy Kynoch, Director – European Operations • Ivonne Brauburger, Director – European Sales • Mark Danis, Manager – UK Corporate Sales • Tim Isik, Manager – UK Channel Sales • Isabelle Gannoun, Manager – Sales France • Jose Blazquez, Regional Manager – Sales Spain & Portugal • Roberto Antonucci, Regional Manager – Sales Italy & Southeast Europe • Markus Boecker, Regional Manager – Sales Germany & Switzerland • Caitriona Toner, Manager – Sales Ireland • Javier Equisoain Blanco, Manager – Regional Sales Benelux Updated Jan. -

Airline Tickets to Frankfurt

Airline Tickets To Frankfurt syphiliticAnatollo remainsand repatriates tunicate his after Calvinist Fonz enhearten so idiomatically! disobediently Burl rappelling or mashes succulently any inimitability. if bloodiest Demountable Bucky refugees Bear orladders unloosed. some You find and airline tickets Are not on time that also be made it would depart from facebook button above and how long periods and conditions and from france, conduct a communal bottle of. Crew were just a price first is not, as eating less enjoyable experience and frankfurt am main, without checked in order number. Please, taxi, please contact our shareholder service center. Ticket prices and seat availability change rapidly and cannot be guaranteed. Search nearby airports for bigger savings. Please give until now search ends to beauty the summer list of results. Eurowings flight from Berlin to Frankfurt am Main, unless having an important reason. Plane with very clean. They kept oscillating between frankfurt am main, star alliance and get order to check if you can only thing again later. Paid in frankfurt, airlines flying to. Travelers like you have slides, frankfurt to frankfurt are available on the tickets to buy your time. This is no hack to trick Tealium into thinking Nativo is on the page sound we can control terms it loads. Eurowings berlin to frankfurt have been checked baggage missing from top notch and airline tickets using content on flights frankfurt international airport is with a few hotels offer? The entertainment, Frankfurt is the largest financial centre in the continental Europe. Turisto will think you work find the cheapest tickets to hill country. -

Airmail Connections Template

Variation Safe 1 – Time Table Summer 2016 From / To Amsterdam SPL Secure Time Table From/To Amsterdam MB/PvH issued March 10 2015 Valid from March 27, 2016 until October 29th, 2016 Validity Days Dep. Arr. Flight Op | Transfer (first) | Transfer (second) period time time number by | City time Flight Op | City time flight Op | number by | number by +1 = one day later +2 = two days later +3 = three days later +4 = four days later 2 Validity Days Dep. Arr. Flight Op | Transfer (first) | Transfer (second) period time time number by | City time Flight Op | City time flight Op | number by | number by AMSTERDAM - SCHIPHOL AIRPORT (AMS) - ABU DHABI - INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (AUH) - 1234567 11:40 20:10 KL449 AMSTERDAM - SCHIPHOL AIRPORT (AMS) - ACCRA - KOTOKA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (ACC) - 1234567 15:25 20:05 KL589 AMSTERDAM - SCHIPHOL AIRPORT (AMS) - ALMATY - AIRPORT (ALA) 27Mar -01May -23---7 15:25 02:00+1 KL409 04May -26Oct --3---7 15:10 01:40+1 KL405 AMSTERDAM - SCHIPHOL AIRPORT (AMS) - ARUBA - REINA BEATRIX AIRPORT (AUA) - 1-3--6- 12:25 16:30 KL765 AMSTERDAM - SCHIPHOL AIRPORT (AMS) - ATHENS - ELEFTHERIOS VENIZELOS AIRPORT (ATH) - 12345-- 12:05 16:20 KL1575 AMSTERDAM - SCHIPHOL AIRPORT (AMS) - BAHRAIN - INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (BAH) - 1-345-7 11:40 20:40 KL435 AMSTERDAM - SCHIPHOL AIRPORT (AMS) - BANGKOK - SUVARNABHUMI INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (BKK) - 1234567 17:45 09:45+1 KL875 AMSTERDAM - SCHIPHOL AIRPORT (AMS) - BARCELONA - AIRPORT (BCN) - 12345-- 14:15 16:25 KL1673 AMSTERDAM - SCHIPHOL AIRPORT (AMS) - BEIJING - CAPITAL INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (PEK) - 1234567 17:35 08:55+1 KL897 AMSTERDAM - SCHIPHOL AIRPORT (AMS) - BONAIRE - FLAMINGO INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (BON) ---4--- 12:25 16:20 KL771 AMSTERDAM - SCHIPHOL AIRPORT (AMS) – BOMBAY/MUMBAI – CHHATRAPATI SHIVAJI (BOM) - ------- xx:xx xx:xx NO FLIGHTS 3 Validity Days Dep. -

Harmonised Annual KPI Report 2020 Download

KPI Annual Report 2020 German Harmonisation Annual KPI Report 2020 Version History: Version Date Remark Author 0.1 14.06.21 Initial Draft Barboff 0.5 21.06.21 Conclusions added, general edits Editorial Board 0.8 16.07.21 Editorial review Editorial Board 0.9 21.07.21 Final edits & review Barboff 1.0 03.08.21 Version for Publication Editorial Board 1.1 05.08.21 List of Abbreviations added Barboff Annual KPI Report Page 2 of 29 German Harmonisation Annual KPI Report 2020 Imprint Publisher: DFS Deutsche Flugsicherung GmbH on behalf of German Harmonisation Initiative A-CDM Germany Am DFS-Campus 10 D-63225 Langen GERMANY Contacts: Erik Sinz & Sebastian Barboff, OZ/AA Airspace & Aerodrome Operations Editorial Board: Sebastian Barboff DFS Deutsche Flugsicherung GmbH Am DFS-Campus 10 D-63225 Langen GERMANY Boris Breug Flughafen München GmbH D-85326 München-Flughafen GERMANY Stefan Hilger Fraport AG Frankfurt Airport Services Worldwide D-60547 Frankfurt am Main GERMANY Nico Ruwe Flughafen Stuttgart GmbH Flughafenstraße 32 D-70629 Stuttgart GERMANY Date: 05 August 2021 Pages: 29 All rights reserved. Any use outside of the limits set by the German Urheberrechtsgesetz requires written permission of the publisher. Violations will be prosecuted in civil and criminal court. This includes copying, translating, microfiching, and storing and processing in electronic systems. DFS Deutsche Flugsicherung GmbH 2021 Annual KPI Report Page 3 of 29 German Harmonisation Annual KPI Report 2020 Content 1 MANAGEMENT SUMMARY 5 2 GERMAN HARMONISATION INITIATIVE A-CDM