Arxiv:1101.1853V1 [Astro-Ph.CO] 10 Jan 2011 † ⋆ .Monreal-Ibero A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Porte Des Étoiles Le Journal Des Astronomes Amateurs Du Nord De La France

la porte des étoiles le journal des astronomes amateurs du nord de la France Numéro 39 - hiver 2018 39 À la une Les environs de la grande nébuleuse d’Orion Auteur : F. Lefebvre et D. Fayolle Date : 16/10/2017 Lieu : Saint-Véran (05) GROUPEMENT D’ASTRONOMES Matériel : APN Canon 1000D et AMATEURS COURRIEROIS astrographe Boren-Simon 8'' F2.8 Adresse postale GAAC - Simon Lericque Édito 12 lotissement des Flandres 62128 WANCOURT On avait déjà raconté beaucoup de choses sur Saint-Véran et son Internet observatoire... On pensait même avoir tout dit... On ne voulait pas Site : http://www.astrogaac.fr se répéter... Et pourtant, la mission Astroqueyras 2017 du GAAC Facebook : https://www.facebook.com/GAAC62 a encore repoussé les limites... Imaginez, une fine équipe de 20 E-mail : [email protected] astronomes amateurs venus de l’ensemble des Hauts-de-France (et même au-delà) envahissant pour une semaine le plus bel Les auteurs de ce numéro observatoire astronomique ouvert aux amateurs ; parmi eux, des Philippe Nonckelynck - membre du GAAC contemplateurs, des dessinateurs, des photographes. Les résultats, E-mail : [email protected] fort nombreux, de cette mission historique nous ont poussé à nouveau à prendre la plume pour causer de ce coin de paradis, Simon Lericque - membre du GAAC E-mail : [email protected] de son ciel, de son observatoire et de ses instruments, et surtout de l’ambiance extraordinaire d’une semaine à 3000 mètres sous Yann Picco - membre du GAAC les étoiles... La belle histoire entre le GAAC et Saint-Véran se E-mail : [email protected] poursuit donc avec cet épais numéro de la porte des étoiles.. -

7.5 X 11.5.Threelines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19267-5 - Observing and Cataloguing Nebulae and Star Clusters: From Herschel to Dreyer’s New General Catalogue Wolfgang Steinicke Index More information Name index The dates of birth and death, if available, for all 545 people (astronomers, telescope makers etc.) listed here are given. The data are mainly taken from the standard work Biographischer Index der Astronomie (Dick, Brüggenthies 2005). Some information has been added by the author (this especially concerns living twentieth-century astronomers). Members of the families of Dreyer, Lord Rosse and other astronomers (as mentioned in the text) are not listed. For obituaries see the references; compare also the compilations presented by Newcomb–Engelmann (Kempf 1911), Mädler (1873), Bode (1813) and Rudolf Wolf (1890). Markings: bold = portrait; underline = short biography. Abbe, Cleveland (1838–1916), 222–23, As-Sufi, Abd-al-Rahman (903–986), 164, 183, 229, 256, 271, 295, 338–42, 466 15–16, 167, 441–42, 446, 449–50, 455, 344, 346, 348, 360, 364, 367, 369, 393, Abell, George Ogden (1927–1983), 47, 475, 516 395, 395, 396–404, 406, 410, 415, 248 Austin, Edward P. (1843–1906), 6, 82, 423–24, 436, 441, 446, 448, 450, 455, Abbott, Francis Preserved (1799–1883), 335, 337, 446, 450 458–59, 461–63, 470, 477, 481, 483, 517–19 Auwers, Georg Friedrich Julius Arthur v. 505–11, 513–14, 517, 520, 526, 533, Abney, William (1843–1920), 360 (1838–1915), 7, 10, 12, 14–15, 26–27, 540–42, 548–61 Adams, John Couch (1819–1892), 122, 47, 50–51, 61, 65, 68–69, 88, 92–93, -

Binocular Challenges

This page intentionally left blank Cosmic Challenge Listing more than 500 sky targets, both near and far, in 187 challenges, this observing guide will test novice astronomers and advanced veterans alike. Its unique mix of Solar System and deep-sky targets will have observers hunting for the Apollo lunar landing sites, searching for satellites orbiting the outermost planets, and exploring hundreds of star clusters, nebulae, distant galaxies, and quasars. Each target object is accompanied by a rating indicating how difficult the object is to find, an in-depth visual description, an illustration showing how the object realistically looks, and a detailed finder chart to help you find each challenge quickly and effectively. The guide introduces objects often overlooked in other observing guides and features targets visible in a variety of conditions, from the inner city to the dark countryside. Challenges are provided for viewing by the naked eye, through binoculars, to the largest backyard telescopes. Philip S. Harrington is the author of eight previous books for the amateur astronomer, including Touring the Universe through Binoculars, Star Ware, and Star Watch. He is also a contributing editor for Astronomy magazine, where he has authored the magazine’s monthly “Binocular Universe” column and “Phil Harrington’s Challenge Objects,” a quarterly online column on Astronomy.com. He is an Adjunct Professor at Dowling College and Suffolk County Community College, New York, where he teaches courses in stellar and planetary astronomy. Cosmic Challenge The Ultimate Observing List for Amateurs PHILIP S. HARRINGTON CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521899369 C P. -

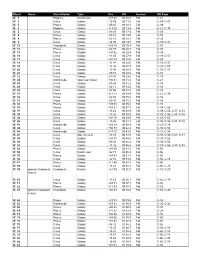

Ngc Catalogue Ngc Catalogue

NGC CATALOGUE NGC CATALOGUE 1 NGC CATALOGUE Object # Common Name Type Constellation Magnitude RA Dec NGC 1 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:07:16 27:42:32 NGC 2 - Galaxy Pegasus 14.2 00:07:17 27:40:43 NGC 3 - Galaxy Pisces 13.3 00:07:17 08:18:05 NGC 4 - Galaxy Pisces 15.8 00:07:24 08:22:26 NGC 5 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:07:49 35:21:46 NGC 6 NGC 20 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 7 - Galaxy Sculptor 13.9 00:08:21 -29:54:59 NGC 8 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:08:45 23:50:19 NGC 9 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.5 00:08:54 23:49:04 NGC 10 - Galaxy Sculptor 12.5 00:08:34 -33:51:28 NGC 11 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.7 00:08:42 37:26:53 NGC 12 - Galaxy Pisces 13.1 00:08:45 04:36:44 NGC 13 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.2 00:08:48 33:25:59 NGC 14 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.1 00:08:46 15:48:57 NGC 15 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.8 00:09:02 21:37:30 NGC 16 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:04 27:43:48 NGC 17 NGC 34 Galaxy Cetus 14.4 00:11:07 -12:06:28 NGC 18 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:09:23 27:43:56 NGC 19 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:10:41 32:58:58 NGC 20 See NGC 6 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 21 NGC 29 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 22 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.6 00:09:48 27:49:58 NGC 23 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:53 25:55:26 NGC 24 - Galaxy Sculptor 11.6 00:09:56 -24:57:52 NGC 25 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.0 00:09:59 -57:01:13 NGC 26 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:10:26 25:49:56 NGC 27 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.5 00:10:33 28:59:49 NGC 28 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.8 00:10:25 -56:59:20 NGC 29 See NGC 21 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 30 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:10:51 21:58:39 -

Far-Ultraviolet Spectroscopy of Star-Forming Regions in Nearby Galaxies: Stellar Populations and Abundance Indicators

Far-Ultraviolet Spectroscopy of Star-Forming Regions in Nearby Galaxies: Stellar Populations and Abundance Indicators 1 William C. Keel Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Alabama, Box 870324, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487; [email protected] Jay B. Holberg Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721; [email protected] Patrick M. Treuthardt Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Alabama, Box 870324, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487 Received ; accepted Submitted to the Astronomical Journal arXiv:astro-ph/0403499v1 20 Mar 2004 1Based on observations made with the NASA-CNES-CSA Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer. FUSE is operated for NASA by the Johns Hopkins University under NASA contract NAS5-32985. –2– ABSTRACT We present FUSE spectroscopy and supporting data for star-forming regions in nearby galaxies, to examine their massive-star content and explore the use of abundance and population indicators in this spectral range for high-redshift galaxies. New far-ultraviolet spectra are shown for four bright H II regions in M33 (NGC 588, 592, 595, and 604), the H II region NGC 5461 in M101, and the starburst nucleus of NGC 7714, supplemented by the very-low-metallicity galaxy I Zw 18. In each case, we see strong Milky Way absorption systems from H2, but intrinsic absorption within each galaxy is weak or undetectable, perhaps because of the “UV bias” in which reddened stars which lie behind molecular-rich areas are also heavily reddened. We see striking changes in the stellar-wind lines from these populations with metallicity, suggesting that C II, C III, C IV, N II, N III, and P V lines are potential tracers of stellar metallicity in star-forming galaxies. -

Interstellar H2 in M 33 Detected with FUSE

A&A 398, 983–991 (2003) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20021725 & c ESO 2003 Astrophysics ? Interstellar H2 in M 33 detected with FUSE H. Bluhm1,K.S.deBoer1,O.Marggraf1,P.Richter2, and B. P. Wakker3 1 Sternwarte, Universit¨at Bonn, Auf dem H¨ugel 71, 53121 Bonn, Germany 2 Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Largo E. Fermi 5, 50125 Firenze, Italy 3 University of Wisconsin–Madison, 475 N. Charter Street, Madison, WI 53706, USA Received 30 October 2002 / Accepted 18 November 2002 Abstract. Fuse spectra of the four brightest H ii regions in M 33 show absorption by interstellar gas in the Galaxy and in M 33. On three lines of sight molecular hydrogen in M 33 is detected. This is the first measurement of diffuse H2 in absorption in a Local Group galaxy other than the Magellanic Clouds. A quantitative analysis is difficult because of the low signal to noise ratio and the systematic effects produced by having multiple objects in the Fuse aperture. We use the M 33 Fuse data to demonstrate in a more general manner the complexity of interpreting interstellar absorption line spectra towards multi-object background 16 17 2 sources. We derive H column densities of 10 to 10 cm− along 3 sight lines (NGC 588, NGC 592, NGC 595). Because of 2 ≈ the systematic effects, these values most likely represent upper limits and the non-detection of H2 towards NGC 604 does not exclude the existence of significant amounts of molecular gas along this sight line. Key words. galaxies: individual: M 33 – ISM: abundances – ISM: molecules – ultraviolet: ISM 1. -

Catálogo Messier Para Observaciones De Cielo Profundo

Catálogo Messier para observaciones de Cielo Profundo ÍNDICE M1 ………………………………………….…3 M28 ……………………………………….38 M2 ……………………………………….…....5 M29 ……………………………………….39 M3 …………………………………………….7 M30 ……………………………………….40 M4 …..………………………………………...9 M31 ……………………………………….41 M5 …..………………………………………..11 M32 ……………………………………….44 M6 …..…………………….………………….13 M33 ……………………………………….46 M7 …..……………………….……………….14 M34 ……………………………………….47 M8 …..………………………….…………….15 M35 ……………………………………….48 M9 …..…………………………….………….16 M36 ……………………………………….50 M10 ….……………………………………….18 M37 ……………………………………….51 M11 ….……………………………………….19 M38 ……………………………………….52 M12 ….……………………………………….20 M39 ……………………………………….53 M13 ….……………………………………….21 M40 ……………………………………….54 M14 ….……………………………………..…22 M41 ……………………………………….55 M15 ….………………………………………..24 M42 ……………………………………….56 M16 ….…………………………………….….26 M43 ……………………………………….58 M17 ….………………………………….….…27 M44 ……………………………………….59 M18 ….………………………………….….…28 M45 ……………………………………….60 M19 ….……………………………………..…29 M46 ……………………………………….63 M20 ….…………………………………….….30 M47 ……………………………………….64 M21 ….…………………………………….….31 M48 ……………………………………….65 M22 ….………………………………….….…32 M49 ……………………………………….66 M23 ….………………………………….….…33 M50 ……………………………………….67 M24 ….………………………………….….…34 M51 ……………………………………….68 M25 ….………………………………….….…35 M52 ……………………………………….69 M26 ….………………………………….….…36 M53 ……………………………………….70 M27 ….……………………………………..…37 M54 ……………………………………….71 1 Catálogo Messier para observaciones de Cielo Profundo M55 …………………………………………....72 M85 ………………………………….………109 M56 ……………………………………………73 M86 ………………………………….………110 M57 ……………………………………………74 M87 ………………………………….………111 -

Interstellar H2 in M 33 Detected with Fuse

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. H2M33 July 7, 2018 (DOI: will be inserted by hand later) ⋆ Interstellar H2 in M 33 detected with Fuse H. Bluhm1, K.S. de Boer1, O. Marggraf1, P. Richter2, and B.P. Wakker3 1 Sternwarte, Universit¨at Bonn, Auf dem H¨ugel 71, 53121 Bonn, Germany 2 Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Largo E. Fermi 5, 50125 Firenze, Italy 3 University of Wisconsin–Madison, 475 N. Charter Street, Madison, WI 53706, USA Received ¡date¿ / Accepted ¡date¿ Abstract. Fuse spectra of the four brightest H ii regions in M 33 show absorption by interstellar gas in the Galaxy and in M 33. On three lines of sight molecular hydrogen in M 33 is detected. This is the first measurement of diffuse H2 in absorption in a Local Group galaxy other than the Magellanic Clouds. A quantitative analysis is difficult because of the low signal to noise ratio and the systematic effects produced by having multiple objects in the Fuse aperture. We use the M 33 Fuse data to demonstrate in a more general manner the complexity of interpreting interstellar absorption line spectra towards multi-object background sources. We derive H2 column − densities of ≈ 1016 to 1017 cm 2 along 3 sight lines (NGC 588, NGC 592, NGC 595). Because of the systematic effects, these values most likely represent upper limits and the non-detection of H2 towards NGC 604 does not exclude the existence of significant amounts of molecular gas along this sight line. Key words. Galaxies: individual: M 33 – ISM: abundances – ISM: molecules – Ultraviolet: ISM 1. Introduction objects. -

The Giant H II Region NGC 588 As a Benchmark for 2D Photoionisation Models

A&A 566, A12 (2014) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201322770 & c ESO 2014 Astrophysics The giant H II region NGC 588 as a benchmark for 2D photoionisation models E. Pérez-Montero1, A. Monreal-Ibero1,2, M. Relaño3,J.M.Vílchez1, C. Kehrig1, and C. Morisset4 1 Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía – CSIC. Apdo. 3004, 18008 Granada, Spain e-mail: [epm;jvm;kehrig]@iaa.es 2 Leibniz-Institut für Astrophysik Potsdam (AIP). An der Sternwarte 16, 14482 Potsdam, Germany 3 Departamento de Física Teórica y del Cosmos, Universidad de Granada, Campus Fuentenueva, 18071 Granada, Spain e-mail: [email protected] 4 Instituto de Astronomía, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Apdo. Postal 70264, 04510, Méx. D. F., Mexico e-mail: [email protected] Received 30 September 2013 / Accepted 18 March 2014 ABSTRACT Aims. We use optical integral field spectroscopy and 8 μm and 24 μm mid-IR observations of the giant H ii region NGC 588 in the disc of M33 as input and constraints for two-dimensional tailor-made photoionisation models under different geometrical approaches. We do this to explore the spatial distribution of gas and dust in the interstellar, ionised medium surrounding multiple massive stars. Methods. Two different geometrical approaches are followed for the modelling structure: i) Each spatial element of the emitting gas is studied individually using models, which assume that the ionisation structure is complete in each element, to look for azimuthal variations across gas and dust. ii) A single model is considered, and the two-dimensional structure of the gas and the dust are assumed to be due to the projection of an emitting sphere onto the sky. -

Wolf–Rayet Stars in M33 – II. Optical Spectroscopy of Emission-Line Stars in Giant H II Regions

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 389, 1033–1040 (2008) doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13633.x Wolf–Rayet stars in M33 – II. Optical spectroscopy of emission-line stars in giant H II regions Laurent Drissen,1 Paul A. Crowther,2 Leonardo Ubeda´ 1 and Pierre Martin3 1Departement´ de physique, de genie´ physique et d’optique, Universite´ Laval, Quebec,´ G1K 7P4, Canada 2Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Sheffield, Hounsfield Road, Sheffield S37RH 3Canada–France–Hawaii Telescope, 65-1238 Mamalahoa Hwy, HI 96743, USA Accepted 2008 June 17. Received 2008 June 16; in original form 2008 April 4 ABSTRACT We present optical spectra of 14 emission-line stars in M33’s giant H II regions NGC 592, 595 and 604: five of them are known Wolf–Rayet (WR) stars, for which we present a better quality spectrogram, eight are WR candidates based on narrow-band imagery and one is a serendipitous discovery. Spectroscopy confirms the power of interference filter imagery to detect emission-line stars down to an equivalent width of about 5 Å in crowded fields. We have also used archival Hubble Space Telescope (HST)/WFPC2 (Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2) images to correctly identify emission-line stars in NGC 592 and 588. Key words: stars: Wolf–Rayet – galaxies: individual: M33 – Local Group. ond most luminous starburst cluster in the Local Group; then, in 1 INTRODUCTION decreasing order of Hα luminosity, NGC 595, 592 and 588. Despite The overwhelming majority of stars in the Universe display absorp- their different galactocentric distances, these four regions have very tion lines in their visible range spectrum. -

Outside-In Stellar Formation in the Spiral Galaxy M33?

Outside-in stellar formation in the spiral galaxy M33? F. Robles-Valdez1⋆, L. Carigi1, and M. Peimbert1 1Instituto de Astronomía Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, AP 70-264, 04510 México DF, México ⋆ E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT We present and discuss results from chemical evolution models for M33. For our models we adopt a galactic formation with an inside-out scenario. The models are built to reproduce three observational constraints of the M33 disk: the radial distributions of the total baryonic mass, the gas mass, and the O/H abundance. From observations, we find that the total baryonic mass profile in M33 has a double exponential behavior, decreasing exponentially for r ≤ 6 kpc, and increasing lightly for r > 6 kpc due to the increase of the gas mass surface density. To adopt a concordant set of stellar and H II regions O/H values, we had to correct the latter for the effect of temperature variations and O dust depletion. Our best model shows a good agreement with the observed radial distributions of: the SFR, the stellar mass, C/H, N/H, Ne/H, Mg/H, Si/H, P/H, S/H, Ar/H, Fe/H, and Z. According to our model, the star formation efficiency is constant in time and space for r ≤ 6 kpc, but the SFR efficiency decreases with time and galactocentric distance for r > 6 kpc. The reduction of the SFR efficiency occurs earlier at higher r. While the galaxy follows the inside-out formation scenario for all r, the stars follow the inside-out scenario only up to r = 6 kpc, but for r > 6 kpc the stars follow an outside-in formation. -

HB-NGC Index

Object Name Constellation Type Dec RA Season HB Page IC 1 Pegasus Double star +27 43 00 08.4 Fall C-21 IC 2 Cetus Galaxy -12 49 00 11.0 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 3 Pisces Galaxy -00 25 00 12.1 Fall C-39 IC 4 Pegasus Galaxy +17 29 00 13.4 Fall C-21, C-39 IC 5 Cetus Galaxy -09 33 00 17.4 Fall C-39 IC 6 Pisces Galaxy -03 16 00 19.0 Fall C-39 IC 8 Pisces Galaxy -03 13 00 19.1 Fall C-39 IC 9 Cetus Galaxy -14 07 00 19.7 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 10 Cassiopeia Galaxy +59 18 00 20.4 Fall C-03 IC 12 Pisces Galaxy -02 39 00 20.3 Fall C-39 IC 13 Pisces Galaxy +07 42 00 20.4 Fall C-39 IC 16 Cetus Galaxy -13 05 00 27.9 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 17 Cetus Galaxy +02 39 00 28.5 Fall C-39 IC 18 Cetus Galaxy -11 34 00 28.6 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 19 Cetus Galaxy -11 38 00 28.7 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 20 Cetus Galaxy -13 00 00 28.5 Fall C-39, C-57 IC 21 Cetus Galaxy -00 10 00 29.2 Fall C-39 IC 22 Cetus Galaxy -09 03 00 29.6 Fall C-39 IC 24 Andromeda Open star cluster +30 51 00 31.2 Fall C-21 IC 25 Cetus Galaxy -00 24 00 31.2 Fall C-39 IC 29 Cetus Galaxy -02 11 00 34.2 Fall C-39 IC 30 Cetus Galaxy -02 05 00 34.3 Fall C-39 IC 31 Pisces Galaxy +12 17 00 34.4 Fall C-21, C-39 IC 32 Cetus Galaxy -02 08 00 35.0 Fall C-39 IC 33 Cetus Galaxy -02 08 00 35.1 Fall C-39 IC 34 Pisces Galaxy +09 08 00 35.6 Fall C-39 IC 35 Pisces Galaxy +10 21 00 37.7 Fall C-39, C-56 IC 37 Cetus Galaxy -15 23 00 38.5 Fall C-39, C-56, C-57, C-74 IC 38 Cetus Galaxy -15 26 00 38.6 Fall C-39, C-56, C-57, C-74 IC 40 Cetus Galaxy +02 26 00 39.5 Fall C-39, C-56 IC 42 Cetus Galaxy -15 26 00 41.1 Fall C-39, C-56, C-57, C-74 IC