Dysfunctional Sacroiliac Joint Pain Following Lumbar Discectomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anterior Reconstruction Techniques for Cervical Spine Deformity

Neurospine 2020;17(3):534-542. Neurospine https://doi.org/10.14245/ns.2040380.190 pISSN 2586-6583 eISSN 2586-6591 Review Article Anterior Reconstruction Techniques Corresponding Author for Cervical Spine Deformity Samuel K. Cho 1,2 1 1 1 https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7511-2486 Murray Echt , Christopher Mikhail , Steven J. Girdler , Samuel K. Cho 1Department of Orthopedics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA Department of Orthopaedics, Icahn 2 Department of Neurological Surgery, Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 425 NY, USA West 59th Street, 5th Floor, New York, NY, USA E-mail: [email protected] Cervical spine deformity is an uncommon yet severely debilitating condition marked by its heterogeneity. Anterior reconstruction techniques represent a familiar approach with a range Received: June 24, 2020 of invasiveness and correction potential—including global or focal realignment in the sagit- Revised: August 5, 2020 tal and coronal planes. Meticulous preoperative planning is required to improve or prevent Accepted: August 17, 2020 neurologic deterioration and obtain satisfactory global spinal harmony. The ability to per- form anterior only reconstruction requires mobility of the opposite column to achieve cor- rection, unless a combined approach is planned. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion has limited focal correction, but when applied over multiple levels there is a cumulative ef- fect with a correction of approximately 6° per level. Partial or complete corpectomy has the ability to correct sagittal deformity as well as decompress the spinal canal when there is an- terior compression behind the vertebral body. -

Spinal Interventional Pain Management and Lumbar Spine Surgery

Spinal Interventional Pain Management and Lumbar Spine Surgery Policy Number: Original Effective Date: MM.06.024 01/01/2014 Line(s) of Business: Current Effective Date: HMO; PPO; QUEST Integration 12/15/2017 Section: Surgery; Medicine Place(s) of Service: Office; Outpatient; Inpatient I. Description The following spinal interventional pain management and lumbar spine surgery procedures require precertification through Magellan Hawaii, formally known as National Imaging Associates, Inc. (NIA): A. Spinal Epidural Injections B. Paravertebral Facet Joint Denervation (radiofrequency neurolysis) C. Paravertebral Facet Joint Injections or Blocks D. Sacroiliac joint injections E. Lumbar Spinal Fusion Surgery II. Administrative Guidelines A. The ordering physician can obtain precertification or consult with Magellan Hawaii by accessing their website at http://www.radmd.com/ or by calling 1 (866) 306-9729, from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., weekdays, Hawaii Time. Refer to the e-library for instructions on navigating the radmd.com website (RadMD Get Started) and requesting precertification/checking the status of a request (RadMD QuickStart). B. For access to the latest clinical guidelines used for precertification, go to www.radmd.com and click on the link entitled View Clinical Guidelines. C. For interventional pain management procedures (epidural injections, facet joint denervation neurolysis, facet joint injections and sacroiliac joint injections), if more than one procedure is planned, a separate precertification number must be obtained for each procedure planned. D. For spinal surgeries (lumbar fusions, lumbar decompressions, and lumbar microdiscectomy), one precertification number should be obtained for the most invasive surgery to be performed. E. Precertification requirements for injection procedures apply only to office and outpatient services (POS 11, 22, or 24). -

Automated Percutaneous and Endoscopic Discectomy

Corporate Medical Policy Automated Percutaneous and Endoscopic Discectomy File Name: percutaneous_discectomy Origination: 9/1991 Last CAP Review: 5/2021 Next CAP Review: 5/2022 Last Review: 5/2021 Description of Procedure or Service Surgical management of herniated intervertebral discs most commonly involves discectomy or microdiscectomy, performed manually through an open incision. Automated percutaneous discectomy involves placement of a probe within the intervertebral disc under image guidance with aspiration of disc material using a suction cutting device. Removal of disc herniations under endoscopic visualization is also being investigated. Endoscopic discectomy involves the percutaneous placement of a working channel under image guidance, followed by visualization of the working space and instruments through an endoscope, and aspiration of disc material. Back pain or radiculopathy related to herniated discs is an extremely common condition and a frequent cause of chronic disability. Although many cases of acute low back pain and radiculopathy will resolve with conservative care, a surgical decompression is often considered when the pain is unimproved after several months and is clearly neuropathic in origin, resulting from irritation of the nerve roots. Open surgical treatment typically consists of discectomy, in which the extruding disc material is excised. When performed with an operating microscope the procedure is known as microdiscectomy. Minimally invasive options have also been researched, in which some portion of the disc is removed or ablated, although these techniques are not precisely targeted at the offending extruding disc material. Ablative techniques include laser discectomy and radiofrequency (RF) decompression. In addition, intradiscal electrothermal annuloplasty is another minimally invasive approach to low back pain. -

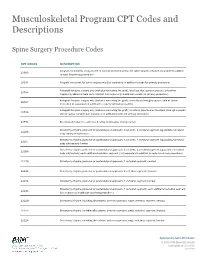

Musculoskeletal Program CPT Codes and Descriptions

Musculoskeletal Program CPT Codes and Descriptions Spine Surgery Procedure Codes CPT CODES DESCRIPTION Allograft, morselized, or placement of osteopromotive material, for spine surgery only (List separately in addition 20930 to code for primary procedure) 20931 Allograft, structural, for spine surgery only (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Autograft for spine surgery only (includes harvesting the graft); local (eg, ribs, spinous process, or laminar 20936 fragments) obtained from same incision (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Autograft for spine surgery only (includes harvesting the graft); morselized (through separate skin or fascial 20937 incision) (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Autograft for spine surgery only (includes harvesting the graft); structural, bicortical or tricortical (through separate 20938 skin or fascial incision) (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) 20974 Electrical stimulation to aid bone healing; noninvasive (nonoperative) Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral 22206 body subtraction); thoracic Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral 22207 body subtraction); lumbar Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral 22208 body subtraction); each additional vertebral segment (List separately in addition to code for -

Biomechanical Evaluation of Relationship of Screw Pullout

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Biomechanical Evaluation of Relationship of Screw Pullout Strength, Insertional Torque, and Bone Mineral Density in the Cervical Spine Charles Alan Reitman, MD, Lyndon Nguyen, and Guy R. Fogel help prevent implant loosening and add rigidity to the plate- Background: Understanding of implant failure mechanisms is im- screw construct. Some screws actually lock to the plate, while portant in the successful utilization of anterior cervical plates. Many in most cases, there is some kind of blocking plate or screw variables influence screw purchase, including the quality of the bone. head expansion to secure the screw to the plate. In these cases, The purpose of this study was to assess the relationship of screw pull- out and screw insertional torque across a wide range of bone mineral the screws are initially placed securely per the surgeon’s own densities (BMDs). perception, in most instances without specific torque control. Screw pullout and stripping (exceeding maximal inser- Methods: A total of 54 cervical vertebrae in 12 cervical spines were tional torque) are possible modes of failure. Some factors af- evaluated for BMD using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scan- fecting the pullout strength of a cancellous bone screw are spe- ning. Actual and perceived peak torques of 3.5-mm anterior cervical cific to the screw design and include the major diameter of the screws were determined at each level followed by screw pullout screw, the length of engagement of the thread, and screw strength testing. thread depth and pitch.4 Furthermore, tapping was found to Results: A high correlation was observed between screw pullout reduce pullout force by an average of 8% compared with non- strength and BMD. -

The Costs and Benefits of Moving to the ICD-10 Code Sets

CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CIVIL JUSTICE service of the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE 6 INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS POPULATION AND AGING The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY organization providing objective analysis and effective SUBSTANCE ABUSE solutions that address the challenges facing the public TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY and private sectors around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Science and Technology View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. This product is part of the RAND Corporation technical report series. Reports may include research findings on a specific topic that is limited in scope; present discus- sions of the methodology employed in research; provide literature reviews, survey instruments, modeling exercises, guidelines for practitioners and research profes- sionals, and supporting documentation; -

Diagnosis and Treatment of Lumbar Disc Herniation with Radiculopathy

Y Lumbar Disc Herniation with Radiculopathy | NASS Clinical Guidelines 1 G Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines for Multidisciplinary ETHODOLO Spine Care M NE I DEL I U /G ON Diagnosis and Treatment of I NTRODUCT Lumbar Disc I Herniation with Radiculopathy NASS Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines Committee D. Scott Kreiner, MD Paul Dougherty, II, DC Committee Chair, Natural History Chair Robert Fernand, MD Gary Ghiselli, MD Steven Hwang, MD Amgad S. Hanna, MD Diagnosis/Imaging Chair Tim Lamer, MD Anthony J. Lisi, DC John Easa, MD Daniel J. Mazanec, MD Medical/Interventional Treatment Chair Richard J. Meagher, MD Robert C. Nucci, MD Daniel K .Resnick, MD Rakesh D. Patel, MD Surgical Treatment Chair Jonathan N. Sembrano, MD Anil K. Sharma, MD Jamie Baisden, MD Jeffrey T. Summers, MD Shay Bess, MD Christopher K. Taleghani, MD Charles H. Cho, MD, MBA William L. Tontz, Jr., MD Michael J. DePalma, MD John F. Toton, MD This clinical guideline should not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding or other acceptable methods of care reason- ably directed to obtaining the same results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specific procedure or treatment is to be made by the physi- cian and patient in light of all circumstances presented by the patient and the needs and resources particular to the locality or institution. I NTRODUCT 2 Lumbar Disc Herniation with Radiculopathy | NASS Clinical Guidelines I ON Financial Statement This clinical guideline was developed and funded in its entirety by the North American Spine Society (NASS). All participating /G authors have disclosed potential conflicts of interest consistent with NASS’ disclosure policy. -

Final Addenda FY 2005

FY 2005 Final Addenda ICD-9-CM Volume 3, Procedures Effective October 1, 2004 Tabular List 00.0 Therapeutic ultrasound Add exclusion term Excludes: diagnostic ultrasound (non-invasive) (88.71-88.79) intracardiac echocardiography [ICE] (heart chamber(s)) (37.28) intravascular imaging (adjunctive) (00.21-00.29) New code 00.16 Pressurized treatment of venous bypass graft [conduit] with pharmaceutical substance Ex-vivo treatment of vessel Hyperbaric pressurized graft [conduit] New code 00.17 Infusion of vasopressor agent New subcategory 00.2 Intravascular imaging of blood vessels Endovascular ultrasonography Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) Code also any synchronous diagnostic or therapeutic procedures Excludes: therapeutic ultrasound (00.01-00.09) New code 00.21 Intravascular imaging of extracranial cerebral vessels Common carotid vessels and branches Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), extracranial cerebral vessels Excludes: diagnostic ultrasound (non-invasive) of head and neck (88.71) New code 00.22 Intravascular imaging of intrathoracic vessels Aorta and aortic arch Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), intrathoracic vessels Vena cava (superior) (inferior) Excludes: diagnostic ultrasound (non-invasive) of other sites of thorax (88.73) New code 00.23 Intravascular imaging of peripheral vessels Imaging of: vessels of arm(s) vessels of leg(s) Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), peripheral vessels Excludes: diagnostic ultrasound (non-invasive) of peripheral vascular system (88.77) New code 00.24 Intravascular imaging of coronary vessels Intravascular -

Procedure: Mri Arthrogram Right Knee Indication

Page 1 of 66 PROCEDURE: MRI ARTHROGRAM RIGHT KNEE INDICATION: Surgery August 2016, patient has persistent pain. ACL and MCL repair. COMPARISON: Preoperative study 10/16/2014. On this study, there is a partial intrasubstance ACL tear greater at the posterior lateral bundle of the intercondylar notch. There was a bipartite patella, although there is some irregularity at the chondral surface. TECHNIQUE: MRI arthrogram protocol was performed, which includes fat-suppressed T1- weighted scans in all three planes, as well as T1-weighted, proton density, and T2 fat-suppressed sequences. The arthrogram portion is performed and dictated separately. _____________________________________________________ FINDINGS: ACL reconstruction: The reconstructed ACL is intact. This is best seen on axial images. There may have been a notchplasty, although the operative report is not available. No evidence of any cystic changes of the interference screws. No evidence of hardware failure. No evidence of iliotibial band friction. No evidence of arthrofibrosis or ligamentization. No evidence of impingement, and the tunnels appear in appropriate alignment. There is no evidence of a pattern of contusion to suggest instability due to ACL insufficiency. Ligaments: PCL is intact. Ligament of Humphrey visible. Faint ligament of Wrisberg is visible on coronal images but not sagittal images. The MCL is thickened, with intermediate signal at the femoral insertion. Tibial insertion is preserved. There is some thickening of the fibular collateral ligament. Iliotibial band is normal, without evidence of impingement. Fibular head and syndesmosis are intact. There is some thickening of the fibular popliteal ligament, arcuate ligament is intact. Popliteal tendon and muscle are preserved. Posterior lateral corner is intact. -

The Road to Recovery AFTER LUMBAR SPINE SURGERY

The Road To Recovery AFTER LUMBAR SPINE SURGERY A DETAILED GUIDE TO YOUR SURGERY AND THE RECOVERY PROCESS FROM THE JOHNS HOPKINS SPINE SERVICE The Road To Recovery after Spine Surgery TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Type of Surgery 6 Preparing for Surgery 7 Day of Surgery 11 Days after Surgery 12 Exercises in the Hospital 13 Going Home after Surgery 14 Ways to Avoid Twisting and Bending after Surgery 17 Proper Lifting Technique 18 Proper Ways to Push and Pull after Surgery 20 Sleeping after Surgery 21 Sitting after Surgery 22 Sitting at Your Desk after Surgery 23 6 Week Follow-Up Appointment 24 Exercises at 6 Weeks after Surgery 25 What if My Expectations of Surgery are Not Met? 27 Additional Resources and Phone Numbers 28 Benefits of Quitting Smoking 29 Hotel Accommodations 31 Johns Hopkins Medical Campus Map 35 2 The Road To Recovery after Spine Surgery This book will: - Prepare you for surgery - Explain what to expect during and after surgery - Guide you through the recovery process The most important thing to remember is the sooner you return to being active – the sooner you will be on the road to recovery. The Johns Hopkins Spine Service is dedicated to returning you to an active lifestyle. Each member of the spine team has contributed to this book and is here to answer any question. You can also access the book on our website at http://www.hopkinsortho.org/surgery_guide.html. Thank you for choosing us! Johns Hopkins Outpatient Center Johns Hopkins at Greenspring Station Department of Orthopaedic Surgery 10753 Falls Road, Suite 215 601 N. -

Following Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion Outcomes

Risk Factors Associated With Failure to Reach Minimal Clinically Important Difference in Patient-Reported Outcomes Following Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion Ankur S. Narain, Fady Y. Hijji, Benjamin Khechen, Brittany E. Haws, Dil V. Patel, Daniel D. Bohl, Kelly H. Yom, Krishna T. Kudaravalli and Kern Singh Int J Spine Surg published online 8 July 2019 http://ijssurgery.com/content/early/2019/07/08/6035 This information is current as of September 27, 2021. Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://ijssurgery.com/alerts The International Journal of Spine Surgery 2397 Waterbury Circle, Suite 1, Aurora, IL 60504, Phone: +1-630-375-1432 © 2019 ISASS. All RightsDownloaded Reserved. from http://ijssurgery.com/ by guest on September 27, 2021 International Journal of Spine Surgery Publish Ahead of Print, published on July 8, 2019 as doi:10.14444/6035 International Journal of Spine Surgery, Vol. 00, No. 00, 0000, pp. 000–000 https://doi.org/10.14444/6035 ÓInternational Society for the Advancement of Spine Surgery Risk Factors Associated With Failure to Reach Minimal Clinically Important Difference in Patient-Reported Outcomes Following Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion ANKUR S. NARAIN, BA, FADY Y. HIJJI, MD, BENJAMIN KHECHEN, BA, BRITTANY E. HAWS, BS, DIL V. PATEL, BS, DANIEL D. BOHL, MD, MPH, KELLY H. YOM, BA, KRISHNA T. KUDARAVALLI, BS, KERN SINGH, MD Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Rush University Medical Center, 1611 West Harrison Street, Suite #300, Chicago, IL 60612 ABSTRACT Background: The minimum clinically importance difference (MCID) represents a threshold for improvements in patient-reported outcomes (PROs) that patients deem important. -

FY 2009 Final Addenda ICD-9-CM Volume 3, Procedures Effective October 1, 2008

FY 2009 Final Addenda ICD-9-CM Volume 3, Procedures Effective October 1, 2008 Tabular 00.3 Computer assisted surgery [CAS] Add inclusion term That without the use of robotic(s) technology Add exclusion term Excludes: robotic assisted procedures (17.41-17.49) New code 00.49 SuperSaturated oxygen therapy Aqueous oxygen (AO) therapy SSO2 SuperOxygenation infusion therapy Code also any: injection or infusion of thrombolytic agent (99.10) insertion of coronary artery stent(s) (36.06-36.07) intracoronary artery thrombolytic infusion (36.04) number of vascular stents inserted (00.45-00.48) number of vessels treated (00.40-00.43) open chest coronary artery angioplasty (36.03) other removal of coronary obstruction (36.09) percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty [PTCA] (00.66) procedure on vessel bifurcation (00.44) Excludes: other oxygen enrichment (93.96) other perfusion (39.97) New Code 00.58 Insertion of intra-aneurysm sac pressure monitoring device (intraoperative) Insertion of pressure sensor during endovascular repair of abdominal or thoracic aortic aneurysm(s) New code 00.59 Intravascular pressure measurement of coronary arteries Includes: fractional flow reserve (FFR) Code also any synchronous diagnostic or therapeutic procedures Excludes: intravascular pressure measurement of intrathoracic arteries (00.67) 00.66 Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty [PTCA] or coronary atherectomy Add code also note Code also any: SuperSaturated oxygen therapy (00.49) 1 New code 00.67 Intravascular pressure measurement of intrathoracic