About Lithophones Bednarik, R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Electrophonic Musical Instruments

G10H CPC COOPERATIVE PATENT CLASSIFICATION G PHYSICS (NOTES omitted) INSTRUMENTS G10 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS; ACOUSTICS (NOTES omitted) G10H ELECTROPHONIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS (electronic circuits in general H03) NOTE This subclass covers musical instruments in which individual notes are constituted as electric oscillations under the control of a performer and the oscillations are converted to sound-vibrations by a loud-speaker or equivalent instrument. WARNING In this subclass non-limiting references (in the sense of paragraph 39 of the Guide to the IPC) may still be displayed in the scheme. 1/00 Details of electrophonic musical instruments 1/053 . during execution only {(voice controlled (keyboards applicable also to other musical instruments G10H 5/005)} instruments G10B, G10C; arrangements for producing 1/0535 . {by switches incorporating a mechanical a reverberation or echo sound G10K 15/08) vibrator, the envelope of the mechanical 1/0008 . {Associated control or indicating means (teaching vibration being used as modulating signal} of music per se G09B 15/00)} 1/055 . by switches with variable impedance 1/0016 . {Means for indicating which keys, frets or strings elements are to be actuated, e.g. using lights or leds} 1/0551 . {using variable capacitors} 1/0025 . {Automatic or semi-automatic music 1/0553 . {using optical or light-responsive means} composition, e.g. producing random music, 1/0555 . {using magnetic or electromagnetic applying rules from music theory or modifying a means} musical piece (automatically producing a series of 1/0556 . {using piezo-electric means} tones G10H 1/26)} 1/0558 . {using variable resistors} 1/0033 . {Recording/reproducing or transmission of 1/057 . by envelope-forming circuits music for electrophonic musical instruments (of 1/0575 . -

I a Comparative Analysis of the Mechanics of Musser Grip, Stevens

A Comparative Analysis of the Mechanics of Musser Grip, Stevens Grip, Cross Grip, and Burton Grip by Adam Eric Berkowitz A Document Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL April 2011 i Copyright © 2011 by Adam Eric Berkowitz ii Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Clair Omar Musser ........................................................................................................................ 12 Musser Grip .................................................................................................................................. 16 Leigh Howard Stevens .................................................................................................................. 19 Stevens Grip .................................................................................................................................. 23 A Comparison of the Musser Grip and the Stevens Grip ............................................................. 27 The Origins of the Cross Grip ....................................................................................................... 30 Cross Grip ..................................................................................................................................... 31 Gary Burton ................................................................................................................................. -

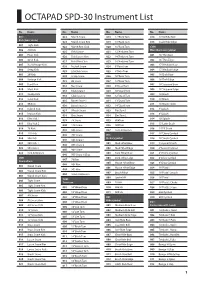

OCTAPAD SPD-30 Instrument List

OCTAPAD SPD-30 Instrument List No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name KIK: 022 March Snare 018 12”Rock Tom 014 Sizzle Ride Bell Kick (bass drum) 023 March Snare Rim 019 13”Rock Tom 015 Sizzle Ride Edge 001 Tight Kick 024 March Rim Click 020 16”Rock Tom CYM: 002 Alt Kick Miscellaneous cymbal 025 Field Snare 021 12”Ambient Tom 003 Fiber Kick 001 16”Thin Bow 026 Field Snare Rim 022 14”Ambient Tom 004 Birch Kick 002 16”Thin Edge 027 Field Rim Click 023 16”Ambient Tom 005 RockVintage Kick 003 17”Medium Bow 028 NuJack Snare 024 6”Roto Tom 006 Deep Kick 004 17”Medium Edge 029 LiteClub Snare 025 8”Roto Tom 007 20”Kick 005 18”Dark Bow 030 2step Snare 026 10”Roto Tom 008 Vintage Kick 006 18”Dark Edge 031 BB Snare 027 12”Roto Tom 009 Hard Kick 007 18”Suspend Bow 032 Box Snare 028 6”Quad Tom 010 Meat Kick 008 18”Suspend Edge 033 Club Snare 1 029 10”Quad Tom 011 NuHip Kick 009 16”Brush 034 Club Snare 2 030 12”Quad Tom 012 Solid Kick 010 18”Brush 035 Barrel Snare 1 031 13”Quad Tom 013 BB Kick 011 18”Brush Sizzle 036 Barrel Snare 2 032 14”Quad Tom 014 Hybrid Kick 012 6”Splash 037 Whack Snare 033 ElecTom 1 015 Impact Kick 013 8”Splash 038 Elec Snare 034 ElecTom 2 016 Elec Kick 1 014 10”Splash 039 78 Snare 035 808Tom 017 Elec Kick 2 015 13”Latin Crash 040 110 Snare 036 909Tom 018 78 Kick 016 14”FX Crash 041 606 Snare 037 Tom Ambience 019 110 Kick 017 16”China Cymbal 042 707 Snare HH: 020 808 Kick Hi-hat cymbal 018 18”Swish Cymbal 043 808 Snare 1 021 909 Kick 1 001 Med Hihat Bow 019 3 Layered Crash 044 808 Snare 2 022 909 Kick 2 002 Med Hihat Edge 020 4”Accent -

(EN) SYNONYMS, ALTERNATIVE TR Percussion Bells Abanangbweli

FAMILY (EN) GROUP (EN) KEYWORD (EN) SYNONYMS, ALTERNATIVE TR Percussion Bells Abanangbweli Wind Accordions Accordion Strings Zithers Accord‐zither Percussion Drums Adufe Strings Musical bows Adungu Strings Zithers Aeolian harp Keyboard Organs Aeolian organ Wind Others Aerophone Percussion Bells Agogo Ogebe ; Ugebe Percussion Drums Agual Agwal Wind Trumpets Agwara Wind Oboes Alboka Albogon ; Albogue Wind Oboes Algaita Wind Flutes Algoja Algoza Wind Trumpets Alphorn Alpenhorn Wind Saxhorns Althorn Wind Saxhorns Alto bugle Wind Clarinets Alto clarinet Wind Oboes Alto crumhorn Wind Bassoons Alto dulcian Wind Bassoons Alto fagotto Wind Flugelhorns Alto flugelhorn Tenor horn Wind Flutes Alto flute Wind Saxhorns Alto horn Wind Bugles Alto keyed bugle Wind Ophicleides Alto ophicleide Wind Oboes Alto rothophone Wind Saxhorns Alto saxhorn Wind Saxophones Alto saxophone Wind Tubas Alto saxotromba Wind Oboes Alto shawm Wind Trombones Alto trombone Wind Trumpets Amakondere Percussion Bells Ambassa Wind Flutes Anata Tarca ; Tarka ; Taruma ; Turum Strings Lutes Angel lute Angelica Percussion Rattles Angklung Mechanical Mechanical Antiphonel Wind Saxhorns Antoniophone Percussion Metallophones / Steeldrums Anvil Percussion Rattles Anzona Percussion Bells Aporo Strings Zithers Appalchian dulcimer Strings Citterns Arch harp‐lute Strings Harps Arched harp Strings Citterns Archcittern Strings Lutes Archlute Strings Harps Ardin Wind Clarinets Arghul Argul ; Arghoul Strings Zithers Armandine Strings Zithers Arpanetta Strings Violoncellos Arpeggione Keyboard -

Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue tubes in a frame. USE clarinet BT double reed instrument UF kechruk a-jaeng alghōzā BT xylophone USE ajaeng USE algōjā anklung (rattle) accordeon alg̲hozah USE angklung (rattle) USE accordion USE algōjā antara accordion algōjā USE panpipes UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, anzad garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. USE imzad piano accordion UF alghōzā anzhad BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah USE imzad NT button-key accordion algōzā Appalachian dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn UF American dulcimer accordion band do nally Appalachian mountain dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi dulcimer, American with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordion orchestra ngoze dulcimer, Kentucky BT instrumental ensemble pāvā dulcimer, lap accordion orchestra pāwā dulcimer, mountain USE accordion band satāra dulcimer, plucked acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute Kentucky dulcimer UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā mountain dulcimer folk bass guitar USE algōjā lap dulcimer BT guitar Almglocke plucked dulcimer acoustic guitar USE cowbell BT plucked string instrument USE guitar alpenhorn zither acoustic guitar, electric USE alphorn Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE electric guitar alphorn USE Appalachian dulcimer actor UF alpenhorn arame, viola da An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE viola d'arame required for the performance of a musical BT natural horn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic arará form. alpine horn A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT performer USE alphorn BT drum adufo alto (singer) arched-top guitar USE tambourine USE alto voice USE guitar aenas alto clarinet archicembalo An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE arcicembalo USE launeddas associated with Western art music and is normally aeolian harp pitched in E♭. -

Klangsteine Exploring the Sound Stones of Hannes Fessmann

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE 18/09/2017 provided by University of Huddersfield Repository Home Sound Stone Background Building My Stone Initial Sound Tests More Klangsteine exploring the sound stones of Hannes Fessmann A thesis submitted by Steven Halliday to the University of Huddersfield for the MA in Music by Research 2016/17 Abstract: The main objective of this research is to fully explore the sonic properties of the Fessmann sound stones and create my own unique stone and virtual instrument. Image Source: Wolfgang Steche Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to Hannes Fessmann, Monty Adkins, Jana Dowling, Jo and Chris Taylor, Damon Waldock, Wolfgang Steche and Neil Hudson for their help and support throughout this project. Home Sound Stone Background Building My Stone Initial Sound Tests More Klangsteine exploring the sound stones of Hannes Fessmann From Caveman to Introduction: Some of the oldest stories of mankind are painted and written on stone, be it the Fessmann. prehistoric rock art of the indigenous people of Australia, Africa, and the Americas or the numerous engravings on the ancient tablets of Egypt and Mesopotamia, stone has always carried the history of the human race. The History of Stone Instruments: "Stone has been used to make music for thousands of years. Some of the earliest playings of music involved the striking of rocks. Ringing rocks have been discovered on various sites across the world, often in close proximity to rock paintings". Rebecca Hildyard. (2010). Ruskin Rocks. Retrieved 15 August, 2017, from https://www.leeds.ac.uk/ruskinrocks/ history%2oof%2omusial%2ostones.htm The earliest forms of tuned percussion are to be found in South East Asia, Vietnam, and China. -

Project for a New Classification of Musical Instruments

Translingual Discourse in Ethnomusicology 2, 2016, 19–25 doi:10.17440/tde008 Project for a New Classification of Musical Instruments ANDRE SCHAEFFNER Originally published as “Projet d'une classification nouvelle des instruments de musique.” Bulletin du Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro 1 (1), 1931, 21-25. Draft translation: Claudia Riehl and Gerd Grupe, with advice on terminology by Susanne Fürniß, copy-editing: Jessica Sloan-Leitner. Editors’ Preface Margaret Kartomi, in her classic monograph On Concepts and Classifications of Musical Instruments (Chicago and London, 1990), highly praises André Schaeffner’s attempt at a new classification: “Unlike the Hornbostel and Sachs classification, Schaeffner’s scheme has not been translated into English and has had little impact outside France. Its comparative novelty or, in other words, its lack of continuity with past classifications, the greater prestige of Hornbostel and Sachs as scholars, and the greater exposure of Hornbostel and Sachs’s classification mediated against the widespread acceptance of Schaeffner’s scheme, despite its elegantly logical quality.” (1990:176) We would like to close this gap by presenting this sketch along with its more extended version entitled, “About a New Systematic Classification of Musical Instruments,” originally published in 1932. To Mr. David Weill In an upcoming study, which shall appear in the Revue musicale (Paris), we hope to elaborate in detail on the motifs which led us to abandon the classification devised by Victor Mahillon (1880) and taken 20 PROJECT FOR A NEW CLASSIFICATION up by E. M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs (1914). Apart from the well- established but imperfect distinction between string, wind, and percussion instruments, this classification has remained the only one adopted by ethnologists. -

The Evolution of the Xylophone Through the Symphonies of Dmitri Shostakovich Justin Lane Alexander Florida State University

Florida State University DigiNole Commons Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School March 2014 The Evolution of the Xylophone Through the Symphonies of Dmitri Shostakovich Justin Lane Alexander Florida State University Follow this and additional works at: http://diginole.lib.fsu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Alexander, Justin Lane, "The Evolution of the Xylophone Through the Symphonies of Dmitri Shostakovich" (2014). Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations. Paper 8722. This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at DigiNole Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigiNole Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE! UNIVERSITY COLLEGE !OF MUSIC ! ! ! ! THE EVOLUTION OF THE! XYLOPHONE THROUGH THE SYMPHONIES OF DMITRI! SHOSTAKOVICH ! ! ! ! ! By! JUSTIN ALEXANDER! ! ! ! ! A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of! Music ! ! ! ! ! ! Degree Awarded: Spring Semester,! 2014 ! ! ! Justin Alexander defended this treatise on March 5, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: ! ! John W. Parks Professor Directing Treatise ! ! Seth Beckman University Representative ! ! Christopher Moore Committee Member ! ! Leon Anderson Committee Member ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. "ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ! This document and degree would not have been possible without the help, guidance, and support of numerous remarkable! individuals: Dr. John W Parks IV, my major professor,! for his guidance, support, and friendship. Dr. Seth Beckman, Dr. -

Proquest Dissertations

Percy Graingers's "The Warriors--Music to an Imaginary Ballet". Innovations in orchestration. The addition of the melodic percussion section as an equal force in 20th century orchestral writing Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Roscigno, John Anthony Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 14:51:15 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288928 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UME films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely aflFect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Rocks That Gong in the Midlands of Kwazulu-Natal

Volume 36, No 3 ISSN 1013-7521 December 2019 ROCKS THAT GONG IN THE MIDLANDS OF KWAZULU-NATAL Annalie Kleinloog Fig. 1: Pointer stone (G01) with significant landscape, peaks and sites My aim with this article is to create an awareness e) made a hollow or metallic sound when hammered amongst nature lovers and conservationists about the with another rock. hidden aspects of rupestral (rock-related) archaeology. This jolted me into much reading, many fieldtrips, With the application of modern technology and bursts of excitement and numerous assumptions. advanced dating methods, this is a rapidly expanding Since then, not a stone has been left unturned, or field of research worldwide, and timelines and theories rather un-gonged, wherever fellow enthusiasts hiked. shift continuously. However, a neglect of our South The obvious next step was to find out who else in the African prehistoric sites because of a micro-focus on world knew about these weird, but wonderful rocks. individual or modern and corporate projects hampers Google overwhelmed our searches. ResearchGate the prospect of South Africa becoming a major role- and JSTOR inundated our queries with exaggerated player in global discoveries and claiming its rightful answers. Taylor & Francis (tandfonline.com) and place in the evolution of theories. Academia poured obscure and famous authors’ names A rocky outcrop caught my attention during my and related titles into our inboxes. The conclusion research into ox-wagon trails in the Midlands of was eye-opening – these metallic sounding stones KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) in 2015. Domineering the were documented on a global scale. small plateau, a pointer stone (Fig. -

Struck Idiophone

Struck idiophone Struck idiophones is one of the categories of idiophones (that is, any musical instrument that creates sound primarily by the instrument as a whole vibrating—without the use of strings or membranes) that are found in the Hornbostel-Sachs system of musical instrument classification. Struck idiophones are categorised as 11 in the Hornbostel-Sachs system. There are two main categories of struck idiophones, directly (111) and indirectly (112) struck. Contents Directly struck (111) Concussion idiophones or clappers (111.1) Percussion idiophones (111.2) Indirectly struck (112) Shaken idiophones or rattles (112.1) Scraped idiophones (112.2) References Directly struck (111) Directly stuck idiophones produce sound resulting from a direct action of the performer as opposed to the indirectly struck idiophones. The player strikes the instrument with a direct action, either by hand or by mechanical intermediate devices, beaters, keyboards, or by pulling ropes, etc. It is definitive that the player can apply clearly defined individual strokes and that the instrument itself is equipped for this kind of percussion. There are two main categories of directly struck idiophones, concussion idiophones (111.1) and percussion idiophones (111.2). Concussion idiophones or clappers (111.1) Two or more complementary sonorous parts are struck against each other. 111.11 Concussion sticks or stick clappers (nearly equal thickness and width). ◾ Clapsticks ◾ Claves 111.12 Concussion plaques or plaque clappers (flat). ◾ Clapper ◾ Guban ◾ Paiban ◾ Pak 1 6 ◾ Slapstick 111.13 Concussion troughs or trough clappers (shallow). ◾ Devil chase 111.14 Concussion vessels or vessel clappers (deep). ◾ Spoons 111.141 Castanets - Natural and hollowed-out vessel clappers.