DESTINATION CONGO: SABENA AIRLINES and the VISUAL LEGACY of CONGOLESE TOURISM Evan Binkley a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Une «Flamandisation» De Bruxelles?

Une «flamandisation» de Bruxelles? Alice Romainville Université Libre de Bruxelles RÉSUMÉ Les médias francophones, en couvrant l'actualité politique bruxelloise et à la faveur des (très médiatisés) «conflits» communautaires, évoquent régulièrement les volontés du pouvoir flamand de (re)conquérir Bruxelles, voire une véritable «flamandisation» de la ville. Cet article tente d'éclairer cette question de manière empirique à l'aide de diffé- rents «indicateurs» de la présence flamande à Bruxelles. L'analyse des migrations entre la Flandre, la Wallonie et Bruxelles ces vingt dernières années montre que la population néerlandophone de Bruxelles n'est pas en augmentation. D'autres éléments doivent donc être trouvés pour expliquer ce sentiment d'une présence flamande accrue. Une étude plus poussée des migrations montre une concentration vers le centre de Bruxelles des migrations depuis la Flandre, et les investissements de la Communauté flamande sont également, dans beaucoup de domaines, concentrés dans le centre-ville. On observe en réalité, à défaut d'une véritable «flamandisation», une augmentation de la visibilité de la communauté flamande, à la fois en tant que groupe de population et en tant qu'institution politique. Le «mythe de la flamandisation» prend essence dans cette visibilité accrue, mais aussi dans les réactions francophones à cette visibilité. L'article analyse, au passage, les différentes formes que prend la présence institutionnelle fla- mande dans l'espace urbain, et en particulier dans le domaine culturel, lequel présente à Bruxelles des enjeux particuliers. MOTS-CLÉS: Bruxelles, Communautés, flamandisation, migrations, visibilité, culture ABSTRACT DOES «FLEMISHISATION» THREATEN BRUSSELS? French-speaking media, when covering Brussels' political events, especially on the occasion of (much mediatised) inter-community conflicts, regularly mention the Flemish authorities' will to (re)conquer Brussels, if not a true «flemishisation» of the city. -

Acte Argeo Final

GEOTHERMAL RESOURCE INDICATIONS OF THE GEOLOGIC DEVELOPMENT AND HYDROTHERMAL ACTIVITIES OF D.R.C. Getahun Demissie Addis Abeba, Ethiopia, [email protected] ABSTRACT Published sources report the occurrence of more than 135 thermal springs in D.R.C. All occur in the eastern part of the country, in association with the Western rift and the associated rifted and faulted terrains lying to its west. Limited information was available on the characteristics of the thermal features and the natural conditions under which they occur. Literature study of the regional distribution of these features and of the few relatively better known thermal spring areas, coupled with the evaluation of the gross geologic conditions yielded encouraging results. The occurrence of the anomalously large number of thermal springs is attributed to the prevalence of abnormally high temperature conditions in the upper crust induced by a particularly high standing region of anomalously hot asthenosphere. Among the 29 thermal springs the locations of which could be determined, eight higher temperature features which occur in six geologic environments were found to warrant further investigation. The thermal springs occur in all geologic terrains. Thermal fluid ascent from depth is generally influenced by faulting while its emergence at the surface is controlled by the near-surface hydrology. These factors allow the adoption of simple hydrothermal fluid circulation models which can guide exploration. Field observations and thermal water sampling for chemical analyses are recommended for acquiring the data which will allow the selection of the most promising prospects for detailed, integrated multidisciplinary exploration. An order of priorities is suggested based on economic and technical criteria. -

Phase 2 : Analyse De L'offre Et De La Demande

BRUXELLES ENVIRONNEMENT Développement d’une stratégie globale de redéploiement du sport dans les espaces verts en Région de Bruxelles-Capitale Phase 2 : Analyse de l’offre et la demande Octobre 2017 1 Bruxelles Environnement – Développement d’une stratégie globale de redéploiement du sport dans les espaces verts en Région de Bruxelles-Capitale Document de travail - Phase 2 – Analyse de l’offre et la demande – Octobre 2017 Table des matières Introduction........................................................................................................................................4 A. Analyse par sport ........................................................................................................................5 1. Méthodologie de l’analyse quantitative ...................................................................................5 1.1. Carte de couverture spatiale par sport .............................................................................9 1.2. Carte de priorisation des quartiers d’intervention par sport .............................................9 2. Méthodologie de l’analyse qualitative ................................................................................... 15 3. Principales infrastructures présentes ..................................................................................... 18 3.1. Pétanque ....................................................................................................................... 18 3.2. Football ........................................................................................................................ -

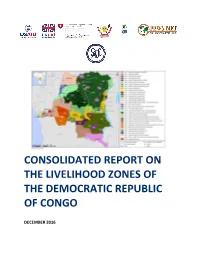

DRC Consolidated Zoning Report

CONSOLIDATED REPORT ON THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DECEMBER 2016 Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 6 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Livelihoods zoning ....................................................................................................................7 1.2 Implementation of the livelihood zoning ...................................................................................8 2. RURAL LIVELIHOODS IN DRC - AN OVERVIEW .................................................................. 11 2.1 The geographical context ........................................................................................................ 11 2.2 The shared context of the livelihood zones ............................................................................. 14 2.3 Food security questions ......................................................................................................... 16 3. SUMMARY DESCRIPTIONS OF THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES .................................................... 18 CD01 COPPERBELT AND MARGINAL AGRICULTURE ....................................................................... 18 CD01: Seasonal calendar .................................................................................................................... -

PASSIE GEEFT VLEUGELS Luchtvaarterfgoed in Musea En Daarbuiten

PASSIE GEEFT VLEUGELS Luchtvaarterfgoed in musea en daarbuiten THEMA LUCHTVAARTERFGOED 1 VOORWOORD Icaros, de brokkenpiloot uit de Griekse mythologie, is beroemder dan zijn vader Daedalos, die er wel in geslaagd is de vlucht van Kreta naar Athene te maken. Terwijl de hoogmoedige Icaros in de Egeïsche Zee stortte, koos Daedalos de gulden middenweg tussen zee en zon en wist veilig te landen, met zijn grote vleugels, gemaakt van vogelveren die hij met bijenwas op een houten constructie had gekleefd. Sindsdien is de mens blijven dromen van vliegen. Fantasierijk zijn de tekeningen die Leonardo da Vinci eind vijftiende eeuw maakte van allerlei vliegende tuigen. Hilarisch zijn de beelden uit de beginjaren van de film van mannen die zich, net als Daedalos, vleugels hebben aangemeten, een sprintje inzetten en klapwiekend van een heuveltje springen om dan, Icaros achterna, neer te vallen. Alles veranderde toen Orville en Wilbur Wright op 17 december 1903 met hun Flyer op het winderige strand bij Kitty Hawk in North Carolina verschenen om geschiedenis te schrijven. De eerste vlucht allertijden duurde 12 seconden en de tweedekker had 37 meter afgelegd. Vanaf dan ging het steeds sneller, verder en hoger, al moesten de pioniers-piloten eerst nog vele keren rechtkrabbelen uit hun neergestorte ‘vliegmachienen’. Dit themanummer schetst de geschiedenis van de luchtvaart, van de eerste vlucht met de ‘montgolfière’ in 1783 tot en met de F-16 van vandaag. Het is een bezoek aan de gigantisch hal van het War Heritage Institute, de nieuwe naam van Legermuseum in Brussel. Het is meteen een tocht langs historische momenten, vooral conflicten, geïllustreerd door vele tientallen vliegtuigen, die vaak boeiende verhalen vertellen. -

A La Découverte De L'histoire D'ixelles

Yves de JONGHE d’ARDOYE, Bourgmestre, Marinette DE CLOEDT, Échevin de la Culture, Paul VAN GOSSUM, Échevin de l’Information et des Relations avec le Citoyen et les membres du Collège échevinal vous proposent une promenade: À LA DÉCOUVERTE DE L’HISTOIRE D’IXELLES (3) Recherches et rédaction: Michel HAINAUT et Philippe BOVY Documents d’archives et photographies: Jean DE MOYE, Michel HAINAUT, Jean-Louis HOTZ, Emile DELABY et les Collections du Musée communal d’Ixelles. ONTENS D OSTERWYCK Réalisation: Laurence M ’O Entre les deux étangs, Alphonse Renard pose devant la maison de Blérot (1914). Ce fascicule a été élaboré en collaboration avec: LE CERCLE D’HISTOIRE LOCALE D’IXELLES asbl (02/515.64.11) Si vous souhaitez recevoir les autres promenades de notre série IXELLES-VILLAGE ET LE QUARTIER DES ÉTANGS Tél.: 02/515.61.90 - Fax: 02/515.61.92 du lundi au vendredi de 9h à 12h et de 14h à 16h Éditeur responsable: Paul VAN GOSSUM, Échevin de l’Information - avril 1998 Cette troisième promenade est centrée sur les abords de la place Danco, le pianiste de jazz Léo Souris et le chef d’orchestre André Flagey et des Étangs. En cours de route apparaîtront quelques belles Vandernoot. Son fils Marc Sevenants, écrivain et animateur, mieux réalisations architecturales représentatives de l’Art nouveau. Elle connu sous le nom de Marc Danval, est sans conteste le spécialiste ès permettra de replonger au cœur de l’Ixelles des premiers temps et jazz et musique légère de notre radio nationale. Comédien de forma- mettra en lumière l’une des activités économiques majeures de son tion, il avait débuté au Théâtre du Parc dans les années ‘50 et profes- histoire, la brasserie. -

Banque D'outremer Was Incorporated on 7 January 1899 Under the Name Compagnie Internationale Pour Le Commerce Et L'industrie

BANQUE D’OUTREMER (COMPAGNIE INTERNATIONALE POUR LE COMMERCE ET L’INDUSTRIE) S.A. René BRION and Jean-Louis MOREAU BNP Paribas Fortis Historical Centre Association pour la Valorisation des Archives d'Entreprises asbl / Vereniging voor de Valorisatie van Bedrijfsarchieven vzw October 2008 I SUMMARY OF THE HISTORY OF THE BANQUE D’OUTREMER The Banque d'Outremer was incorporated on 7 January 1899 under the name Compagnie Internationale pour le Commerce et l'Industrie. Its initial capital was 32.5 million Belgian francs, divided into 65 000 shares with a nominal value of 500 francs. Numerous investment banks subscribed to these shares: the Société Générale de Belgique/Generale Maatschappij van België, for 9,420 shares; the Banque Léon Lambert, for 4,800; the Banque de Bruxelles firm underwrote 2,600 securities; Franz Philippson also took 2,600; Balser & Co., for 2,600; the Banque Liégeoise, for 2,000; Joseph Devolder, for 2,280; Jules Urban, Albert Thys, Georges de Laveleye, Jean Cousin and Hippolyte Lippens, for 1,800 each; R. de Bauer, Georges Brugmann, Ernest Grisar, Alfred Havenith and Alfred Simonis, each for 1,000 shares; the Caisse Commerciale de Bruxelles, Cassel & Cie, J. Matthieu & Fils, each for 800 securities. In addition, three foreign groups subscribed to the capital: a French group, allied to the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas (12,000 securities); a German group drawn by Deutsche Bank AG , from Berlin (7,000 securities); and a smaller group of British investors which included the brothers Stern, Ernest Cassel and Sir Vincent Caillard (2,500 securities). The first meeting of the Board of Directors reflected the diversity of the subscribers. -

Heritage Days 15 & 16 Sept

HERITAGE DAYS 15 & 16 SEPT. 2018 HERITAGE IS US! The book market! Halles Saint-Géry will be the venue for a book market organised by the Department of Monuments and Sites of Brussels-Capital Region. On 15 and 16 September, from 10h00 to 19h00, you’ll be able to stock up your library and take advantage of some special “Heritage Days” promotions on many titles! Info Featured pictograms DISCOVER Organisation of Heritage Days in Brussels-Capital Region: Regional Public Service of Brussels/Brussels Urbanism and Heritage Opening hours and dates Department of Monuments and Sites a THE HERITAGE OF BRUSSELS CCN – Rue du Progrès/Vooruitgangsstraat 80 – 1035 Brussels c Place of activity Telephone helpline open on 15 and 16 September from 10h00 to 17h00: Launched in 2011, Bruxelles Patrimoines or starting point 02/204.17.69 – Fax: 02/204.15.22 – www.heritagedays.brussels [email protected] – #jdpomd – Bruxelles Patrimoines – Erfgoed Brussel magazine is aimed at all heritage fans, M Metro lines and stops The times given for buildings are opening and closing times. The organisers whether or not from Brussels, and reserve the right to close doors earlier in case of large crowds in order to finish at the planned time. Specific measures may be taken by those in charge of the sites. T Trams endeavours to showcase the various Smoking is prohibited during tours and the managers of certain sites may also prohibit the taking of photographs. To facilitate entry, you are asked to not B Busses aspects of the monuments and sites in bring rucksacks or large bags. -

A Colonial Genealogy of Violence Against Tutsi Women in The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Gender-Based Violence and Submerged Histories: A Colonial Genealogy of Violence Against Tutsi Women in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Gender Studies by Helina Asmelash Beyene 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Gender-Based Violence and Submerged Histories: A Colonial Genealogy of Violence Against Tutsi Women in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide by Helina Asmelash Beyene Doctor of Philosophy in Gender Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Sondra Hale, Chair My dissertation is a genealogical study of gender-based violence (GBV) during the 1994 Rwandan genocide. A growing body of feminist scholarship argues that GBV in conflict zones results mainly from a continuum of patriarchal violence that is condoned outside the context of war in everyday life. This literature, however, fails to account for colonial and racial histories that also inform the politics of GBV in African conflicts. My project examines the question of the colonial genealogy of GBV by grounding my inquiry within postcolonial, transnational and intersectional feminist frameworks that center race, historicize violence, and decolonize knowledge production. I employ interdisciplinary methods that include (1) discourse analysis of the gender-based violence of Belgian rule and Tutsi women’s iconography in colonial texts; (2) ii textual analysis of the constructions of Tutsi women’s sexuality and fertility in key official documents on overpopulation and Tutsi refugees in colonial and post-independence Rwanda; and (3) an ethnographic study that included leading anti gendered violence activists based in Kigali, Rwanda, to assess how African feminists account for the colonial legacy of gendered violence in the 1994 genocide. -

Prof. Paul Stephen Dempsey

AIRLINE ALLIANCES by Paul Stephen Dempsey Director, Institute of Air & Space Law McGill University Copyright © 2008 by Paul Stephen Dempsey Before Alliances, there was Pan American World Airways . and Trans World Airlines. Before the mega- Alliances, there was interlining, facilitated by IATA Like dogs marking territory, airlines around the world are sniffing each other's tail fins looking for partners." Daniel Riordan “The hardest thing in working on an alliance is to coordinate the activities of people who have different instincts and a different language, and maybe worship slightly different travel gods, to get them to work together in a culture that allows them to respect each other’s habits and convictions, and yet work productively together in an environment in which you can’t specify everything in advance.” Michael E. Levine “Beware a pact with the devil.” Martin Shugrue Airline Motivations For Alliances • the desire to achieve greater economies of scale, scope, and density; • the desire to reduce costs by consolidating redundant operations; • the need to improve revenue by reducing the level of competition wherever possible as markets are liberalized; and • the desire to skirt around the nationality rules which prohibit multinational ownership and cabotage. Intercarrier Agreements · Ticketing-and-Baggage Agreements · Joint-Fare Agreements · Reciprocal Airport Agreements · Blocked Space Relationships · Computer Reservations Systems Joint Ventures · Joint Sales Offices and Telephone Centers · E-Commerce Joint Ventures · Frequent Flyer Program Alliances · Pooling Traffic & Revenue · Code-Sharing Code Sharing The term "code" refers to the identifier used in flight schedule, generally the 2-character IATA carrier designator code and flight number. Thus, XX123, flight 123 operated by the airline XX, might also be sold by airline YY as YY456 and by ZZ as ZZ9876. -

Delta Air Lines Inc /De

DELTA AIR LINES INC /DE/ FORM 10-K (Annual Report) Filed 09/28/98 for the Period Ending 06/30/98 Address HARTSFIELD ATLANTA INTL AIRPORT 1030 DELTA BLVD ATLANTA, GA 30354-1989 Telephone 4047152600 CIK 0000027904 Symbol DAL SIC Code 4512 - Air Transportation, Scheduled Industry Airline Sector Transportation Fiscal Year 12/31 http://www.edgar-online.com © Copyright 2015, EDGAR Online, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Distribution and use of this document restricted under EDGAR Online, Inc. Terms of Use. DELTA AIR LINES INC /DE/ FORM 10-K (Annual Report) Filed 9/28/1998 For Period Ending 6/30/1998 Address HARTSFIELD ATLANTA INTL AIRPORT 1030 DELTA BLVD ATLANTA, Georgia 30354-1989 Telephone 404-715-2600 CIK 0000027904 Industry Airline Sector Transportation Fiscal Year 12/31 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10 -K [X] ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(D) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 1998 OR [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(D) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 COMMISSION FILE NUMBER 1-5424 DELTA AIR LINES, INC. (EXACT NAME OF REGISTRANT AS SPECIFIED IN ITS CHARTER) DELAWARE 58-0218548 (STATE OR OTHER JURISDICTION OF (I.R.S. EMPLOYER INCORPORATION OR ORGANIZATION) IDENTIFICATION NO.) HARTSFIELD ATLANTA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT POST OFFICE BOX 20706 30320 ATLANTA, GEORGIA (ADDRESS OF PRINCIPAL EXECUTIVE OFFICES) (ZIP CODE) REGISTRANT'S TELEPHONE NUMBER, INCLUDING AREA CODE: (404) 715-2600 SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(B) -

Belgian Aerospace

BELGIAN AEROSPACE Chief editor: Fabienne L’Hoost Authors: Wouter Decoster & Laure Vander Graphic design and layout: Bold&pepper COPYRIGHT © Reproduction of the text is authorised provided the source is acknowledged Date of publication: June 2018 Printed on FSC-labelled paper This publication is also available to be consulted at the website of the Belgian Foreign Trade Agency: www.abh-ace.be BELGIAN AEROSPACE TECHNOLOGIES TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 PRESENTATION OF THE SECTOR 4-35 SECTION 1 : BELGIUM AND THE AEROSPACE INDUSTRY 6 SECTION 2 : THE AERONAUTICS INDUSTRY 10 SECTION 3 : THE SPACE INDUSTRY 16 SECTION 4 : BELGIAN COMPANIES AT THE FOREFRONT OF NEW AEROSPACE TRENDS 22 SECTION 5 : STAKEHOLDERS 27 CHAPTER 2 SUCCESS STORIES IN BELGIUM 36-55 ADVANCED MATERIALS & STRUCTURES ASCO INDUSTRIES 38 SABCA 40 SONACA 42 PLATFORMS & EMBEDDED SYSTEMS A.C.B. 44 NUMECA 46 THALES ALENIA SPACE 48 SERVICES & APPLICATIONS EMIXIS 50 SEPTENTRIO 52 SPACEBEL 54 CHAPTER 3 DIRECTORY OF COMPANIES 56-69 3 PRESENTATION OF THE SECTOR PRESENTATION OF THE SECTOR SECTION 1 By then, the Belgian government had already decided it would put out to tender 116 F-16 fighter jets for the Belgian army. This deal, still known today as “the contract of the BELGIUM AND THE century” not only brought money and employment to the sector, but more importantly, the latest technology and AEROSPACE INDUSTRY know-how. The number of fighter jets bought by Belgium exceeded that of any other country at that moment, except for the United States. In total, 1,811 fighters were sold in this batch. 1.1 Belgium’s long history in the aeronautics industry This was good news for the Belgian industry, since there was Belgium’s first involvement in the aeronautics sector was an agreement between General Dynamics and the European related to military contracts in the twenties.