Using West Side Story As a Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sondheim's Putting It Together Gathers More Than 30 Songs From

CSFINEARTSCENTER.ORG Contact: Dori Mitchell, Director of Communications 719.477.4312; [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Sondheim’s Putting It Together gathers more than 30 songs from award‐winning works COLORADO SPRINGS (Aug. 10, 2015) This musical revue showcases the songs of Stephen Sondheim, America’s most‐awarded living musical theatre composer. Featuring nearly 30 Sondheim songs from at least a dozen of his award‐winning shows (including A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Into the Woods, Sweeney Todd, Company and Follies), this one‐of‐a‐kind compilation celebrates Sondheim’s incomparable career in musical theatre. “Stephen Sondheim has written some of the best musical theatre of the last 50 years,” says Performing Arts Director Scott RC Levy, “and will go down in history as one of the most important American composers of the 20th Century. The FAC has a strong history of producing his work, and when thinking of which show of his to do next, I thought of this piece, which features so much of his beautiful music from pieces throughout his career.” The FAC production features an all‐star cast, including Max Ferguson, Sally Hybl, Jordan Leigh, Scott RC Levy and Mackenzie Sherburne. Nathan Halvorson directs and choreographs. Sondheim has won the Kennedy Center Lifetime Achievement Award, a Pulitzer Prize, an Academy Award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, eight Grammy Awards, 12 Tony Awards, 16 Drama Desk Awards and six Olivier Awards. The FAC has produced 10 Sondheim works, including Into the Woods, Funny Thing Happened…, Assassins and Sweeney Todd since 1989. -

West Side Story

West Side Story West Side Story is an American musical with a book rary musical adaptation of Romeo and Juliet . He prpro-o- byby Arthur Laurents, mmususiic bbyy Leonard Bernstein,, posed that the plot focus on the conflict between an Irish libretto/lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, and conception and Catholic family and a Jewish family living on the Lower choreography byby Jerome Robbins..[1] It was inspired by East Side ofof Manhattan,,[6] during the Easter–Passover William Shakespeare's play Romeo and Juliet .. season. The girl has survivvived the Holocaust and emi- The story is set in the Upper West Side neighborhood grated from Israel; the conflict was to be centered around in New York City in the mid-1950s, an ethnic, blue- anti-Semitism of the Catholic “Jets” towards the Jewish “Emeralds” (a name that made its way into the script as collar ne neighighborhood. (In the early 1960s much of thethe [7] neineighborhood would be clecleared in anan urban renewal a reference). Eager to write his first musical, Laurents project for the Lincoln Center, changing the neighbor- immediately agreed. Bernstein wanted to present the ma- hood’s character.)[2][3] The musical explores the rivalry terial in operatic form, but Robbins and Laurents resisted between the Jets and the Sharks, two teenage street gangs the suggestion. They described the project as “lyric the- of different ethnic backgrounds. The members of the ater”, and Laurents wrote a first draft he called East Side Sharks, from Puerto Rico, are taunted by the Jets, a Story. Only after he completed it did the group realize it white gang.[4] The young protagonist, Tony, a former was little more than a musicalization of themes that had member of the Jets and best friend of the gang leader, alreadybeencoveredinin plaplaysys liklikee Abie’s Irish Rose. -

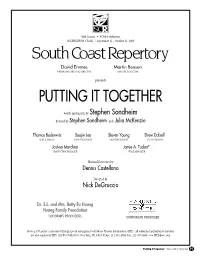

Putting It Together

46th Season • 437th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / September 11 - October 11, 2009 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing ArtiStic director ArtiStic director presents PUTTING IT TOGETHER words and music by Stephen Sondheim devised by Stephen Sondheim and Julia McKenzie Thomas Buderwitz Soojin Lee Steven Young Drew Dalzell Scenic deSign coStume deSign Lighting deSign Sound deSign Joshua Marchesi Jamie A. Tucker* Production mAnAger StAge mAnAger musical direction by Dennis Castellano directed by Nick DeGruccio Dr. S.L. and Mrs. Betty Eu Huang Huang Family Foundation honorAry ProducerS corPorAte Producer Putting It Together is presented through special arrangement with music theatre international (mti). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by mti. 421 West 54th Street, new york, ny 10019; Phone: 212-541-4684 Fax: 212-397-4684; www.mtiShows.com Putting It Together• SOUTH COA S T REPE R TO R Y P1 THE CAST (in order of appearance) Matt McGrath* Harry Groener* Niki Scalera* Dan Callaway* Mary Gordon Murray* MUSICIANS Dennis Castellano (conductor/keyboards), John Glaudini (synthesizer), John Reilly (woodwinds), Louis Allee (percussion) SETTING A New York penthouse apartment. Now. LENGTH Approximately two hours including one 15-minute intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting ................................................................................ Joanne DeNaut, CSA Dramaturg .......................................................................... Linda Sullivan Baity Assistant Stage Manager ............................................................. -

West Side Story

The United States Air Force Academy Bluebards Theatre Troupe Credits Proudly Presents Officer in Charge Lt Col Michelle Ruehl Master Carpenter Jandy Viloria Audio Technician Stan Sakamoto WEST Stage Crew RATTEX Dramaturg Dr. Marc Napolitano SIDE Support Team Flute/piccolo Erica Drakes STORY Bassoon Micaela Cuneo Based on a Conception of Trombone Sam Voss JEROME ROBBINS Violin Jared Helm French Horn Claire Badger Trumpet Josiah Savoie Trombone Braxton Sesler Percussion Matt Fleckenstein Musicians Piano Megan Getlinger Music by Lyrics by Trumpet Sean Castillo Clarinet Rose Bruns Trumpet Tom McCurdy Violin Kat Kowar Violin Matt Meno Entire Original Production Violin Nishanth Kalavakolanu Book by Directed and Choreographed by Bluebards offers its thanks to DFENG, RATTEX, and the Falcon Theater Founda- tion; without their support, this production would not have been possible. The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production12 is strictly prohibited. 1 Who’s Who in the Cast and Crew “WEST SIDE STORY” not sing or dance, he decided to try out for the spring musical! After Based on a Conception of JEROME ROBBINS taking a year off to search the moon for the secret to great singing and dancing, Kevin has returned to Bluebards (unfortunately, people on the moon dance differently than the people of Earth). He is an avid reader who enjoys nerding-out with fellow nerds about the nerdiest subjects. Book by ARTHUR LAURENTS Kevin would like to thank the cast/crew, with a special nod to Lt Col Music by LEONARD BERNSTEIN Ruehl for ensuring USAFA’s drama nerds have a home in Bluebards. -

WEST SIDE STORY.Pages

2015-2016 SEASON 2015-2016 SEASON Teacher Resource Guide ! and Lesson Plan Activities Featuring general information about our production along with some creative activities Tickets: thalian.org! !to help you make connections to your classroom curriculum before and after the show. ! 910-251-1788 ! The production and accompanying activities ! address North Carolina Essential Standards in Theatre or! Arts, Goal A.1: Analyze literary texts & performances. ! CAC box office 910-341-7860 Look! for this symbol for other curriculum connections. West Side Story! ! Book by: Arthur Laurents Music by: Leonard Bernstein Lyrics by: Stephen Sondheim ! ! Based on Conception of: Jerome Robbins! Based on Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet! October 9-11! and 16-18! ! 7:00 PM Thursday - Saturday! and 3:00PM Saturday & Sunday! Hannah Block Historic USO! / Community Arts Center! Second Street Stage 120 South 2nd Street (Corner of Orange) Resource! About this Teaching Resource! This Teaching Resource is designed to help build new partnerships that employ theatre and the Summery:! arts to address some of today’s pressing issues such as youth violence, bullying, gangs, ! interracial tensions, youth-police relations and cultural conflict. This guide provides a perfect ! ! opportunity to partner with law enforcement, schools, youth-based organizations, and community Page 2! groups to develop new approaches to gang prevention.! About the Creative Team, ! Summery of the Musical! About the Musical & Its Relevance for Today! ! Marking its 58th anniversary, West Side Story provides the backdrop to an exploration! Page 3! of youth gangs, youth-police relationships, prejudice and the romance of two young people caught Character & Story Parallels of in a violent cross-cultural struggle.The electrifying music of Leonard Bernstein and the prophetic West Side Story and lyrics of Stephen Sondheim hauntingly paint a picture as relevant today as it was more than 58 Romeo & Juliet ! years ago. -

East Side West Side

WRITINGS OF JOHN MAUCERI JOHNMAUCERI.COM Prologue to Mr. Mauceri's book, "Celebrating West Side East Side, West Side – Story" published by the University of North Carolina School of the Arts 50 Years On How can one measure West Side Story? Do we compare it to the other Broadway shows of 1957? Do we value it because of its influence on music theater? Can we speak of it in terms of other musical versions of Romeo and Juliet? Do we quantify it in terms of the social history of its time? And, most of all, fifty years after its opening night on Broadway, does it mean something important to us today? The answer to all those questions is yes, of course. The fiftieth anniversary of a work of performing art is most telling and significant. That is because after a half century the work has passed out of its contemporary phase and is either becoming a classic or has been forgotten altogether. Fifty years on, members of the original creative team are generally still able to pass on what they experienced once upon a time, and yet, for many, it is an opportunity to experience and judge it for the very first time. Rereading an original Playbill magazine from the week of February 3, 1958 (I was twelve years old when I saw the show), is indeed a cause for multiple surprises and discoveries. Consider the musicals playing on Broadway that week: Bells are Ringing, about a telephone operator; Jamaica, a new Harold Arlen musical with Lena Horne; Li’l Abner, based on a popular comic strip; My Fair Lady with Julie Andrews, New Girl in Town, based on O’Neil’s Anna Christie; Tony Randall starring in Oh, Captain!, based on the Alec Guinness film The Captain’s Paradise; The Music Man with Robert Preston and Barbara Cook. -

Determining Stephen Sondheim's

“I’VE A VOICE, I’VE A VOICE”: DETERMINING STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE THROUGH A MUSIC-THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF HIS THEATER WORKS BY ©2011 PETER CHARLES LANDIS PURIN Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ___________________________ Chairperson Dr. Scott Murphy ___________________________ Dr. Deron McGee ___________________________ Dr. Paul Laird ___________________________ Dr. John Staniunas ___________________________ Dr. William Everett Date Defended: August 29, 2011 ii The Dissertation Committee for PETER PURIN Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “I’VE A VOICE, I’VE A VOICE”: DETERMINING STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE THROUGH A MUSIC-THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF HIS THEATER WORKS ___________________________ Chairperson Dr. Scott Murphy Date approved: August 29, 2011 iii Abstract This dissertation offers a music-theoretic analysis of the musical style of Stephen Sondheim, as surveyed through his fourteen musicals that have appeared on Broadway. The analysis begins with dramatic concerns, where musico-dramatic intensity analysis graphs show the relationship between music and drama, and how one may affect the interpretation of events in the other. These graphs also show hierarchical recursion in both music and drama. The focus of the analysis then switches to how Sondheim uses traditional accompaniment schemata, but also stretches the schemata into patterns that are distinctly of his voice; particularly in the use of the waltz in four, developing accompaniment, and emerging meter. Sondheim shows his harmonic voice in how he juxtaposes treble and bass lines, creating diagonal dissonances. -

INTO the WOODS Stephen Sondheim (Music and Lyrics) and James Lapine (Book) Directed by Susi Damilano Music Director: Dave Dobrusky Choreography: Kimberly Richards

Press Release For immediate release May 2014 [email protected] Download Hi Res photos here INTO THE WOODS Stephen Sondheim (music and lyrics) and James Lapine (book) Directed by Susi Damilano Music Director: Dave Dobrusky Choreography: Kimberly Richards June 24th to September 6th Previews June 24 – June 27 at 8pm Tuesdays through Thursdays at 7pm, Fridays and Saturdays at 8pm Saturdays at 3pm and Sundays at 2pm (except 6/29) PRESS OPENING: Saturday, June 28th at 8pm San Francisco, CA (May 2014) – San Francisco Playhouse (Artistic Director Bill English & Producing Director Susi Damilano) concludes its provocative eleventh season with Into the Woods by Stephen Sondheim (music and lyrics) and James Lapine (book). What happens after “happily ever after?” Fractured fairy tales of a darker hue provide the context for Into the Woods, which deconstructs the Brothers Grimm by way of “The Twilight Zone.” While the faces and names are familiar, Cinderella, Rapunzel, Little Red Riding Hood, Jack in the Beanstalk and company inhabit a sylvan neighborhood in which witches and bakers are next-door neighbors, handsome princes from once-parallel fables are competitive (and equally vain) brothers, and all the stories intersect through unexpected new plot twists. Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s beloved musical intertwines classic fairytales with a contemporary edge to tell stories of wishes granted and “the price” paid. Susi Damilano (Director), Dave Dobrusky (Music Director) and Kimberly Richards (Choreographer) will team up to bring a fresh twist to this familiar tale by adding a time-travelling boy, Ian DeVaynes to the Bay Area cast that features: Louis Parnell* (Narrator), Safiya Fredericks* (Witch), El Beh (Baker’s Wife), Keith Pinto* (Baker), Tim Homsley* (Jack), Joan Mankin* (Jack’s Mom), Monique Hafen* (Cinderella), Becka Fink (Cinderella’s Stepmom), identical twins, Lily and Michelle Drexler (Cinderella’s Stepsisters), Noelani Neal (Rapunzel), Corinne Proctor (Red), Ryan McCrary and Jeffrey Adams (Princes/Wolves) and John Paul Gonzales (Steward). -

West Side Story Previous Recordings

WEST SIDE STORY PREVIOUS RECORDINGS 1957 Original Broadway Cast Recording 1CD (Columbia Masterworks) Carol Lawrence, Larry Kert (songs only) Prologue (3:50), "Jet Song" (2:06), "Something's Coming" (2:37), The Dance at the Gym (3:02), "Maria" (2:37), "Tonight" (3:53), "America" (4:32), "Cool" (3:58), "One Hand, One Heart" (3:02), "Tonight (Quintet)" (3:38), The Rumble (2:44), "I Feel Pretty" (2:46), "Somewhere (Ballet)" (7:33), "Gee, Officer Krupke" (4:02), "A Boy Like That" / "I Have a Love" (4:15), Finale (1:59) 1961 Original Motion Picture Soundtrack 1CD (Sony/Columbia/Legacy) Natalie Wood, Russy Tamblyn (songs only) Overture (4:39), "Jet Song" (2:06), "Something's Coming" (2:32), "Dance at the Gym" (9:24), "Maria" (2:34), "America" (4:59), "Tonight" (5:43), "Gee, Officer Krupke" (4:14), "I Feel Pretty" (3:35), "One Hand, One Heart" (3:02), "Quintet" (3:22),"The Rumble" (2:39), "Somewhere" (2:02), "Cool" (4:21), "A Boy Like That / I Have a Love" (4:28), End Credits (5:05) 1985 Leonard Bernstein Recording 2CD (Deutsche Grammophon) Te Kanawa, Jose Carreras (full score) 77:08 mins. Cast recording. Includes 21:38 mins. symphonic suite from "On the Waterfront” 1993 London Studio recording 1CD (Warner Classics) Michael Ball, Barbara Bonney (songs only) Prologue (4:42), "Jet Song" (2:47), "Something's Coming" (2:29), The Dance at the Gym: Blues (2:03) / Promenade (0:20) / Mambo (2:19) / Cha-Cha (1:01) / Meeting Scene (1:29) / Jump (1:00), "Maria" (3:03), Balcony Scene ("Tonight") (5:55), "America" (5:01), "Cool" (5:01), "One Hand, One -

Broadway 1 a (1893-1927) BROADWAY and the AMERICAN DREAM

EPISODE ONE Give My Regards to Broadway 1 A (1893-1927) BROADWAY AND THE AMERICAN DREAM In the 1890s, immigrants from all over the world came to the great ports of America like New York City to seek their fortune and freedom. As they developed their own neighborhoods and ethnic enclaves, some of the new arrivals took advantage of the stage to offer ethnic comedy, dance and song to their fellow group members as a much-needed escape from the hardships of daily life. Gradually, the immigrants adopted the characteristics and values of their new country instead, and their performances reflected this assimilation. “Irving Berlin has no place in American music — he is American music.” —composer Jerome Kern My New York (excerpt) Every nation, it seems, Sailed across with their dreams To my New York. Every color and race Found a comfortable place In my New York. The Dutchmen bought Manhattan R Island for a flask of booze, E V L U C Then sold controlling interest to Irving Berlin was born Israel Baline in a small Russian village in the Irish and the Jews – 1888; in 1893 he emigrated to this country and settled in the Lower East Side of And what chance has a Jones New York City. He began his career as a street singer and later turned to With the Cohens and Malones songwriting. In 1912, he wrote the words and music to “Alexander’s Ragtime In my New York? Band,” the biggest hit of its day. Among other hits, he wrote “Oh, How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning,” “What’ll I Do?,” “There’s No Business Like —Irving Berlin, 1927 Show Business,” “Easter Parade,” and the patriotic “God Bless America,” in addition to shows like Annie Get Your Gun. -

Educating About the Works of Stephen Sondheim Through Parody

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020- 2020 How Artists Can Capture Us: Educating About the Works of Stephen Sondheim Through Parody Jarrett Poore University of Central Florida Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020- by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Poore, Jarrett, "How Artists Can Capture Us: Educating About the Works of Stephen Sondheim Through Parody" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020-. 117. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020/117 HOW ARTISTS CAN CAPTURE US: EDUCATING ABOUT THE WORKS OF STEPHEN SONDHEIM THROUGH PARODY By JARRETT POORE B.F.A, University of Central Florida 2017 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Theatre in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2020 © Jarrett Mark Poore 2020 ii ABSTRACT This thesis examined the modern renaissance man and his relationship between musical theatre history and parody; it examined how the modern artist created, produced, and facilitated an original parody in which humor can both influence and enhance an individual’s interest in the art form. In the creation and production of The Complete Works of Stephen Sondheim [abridged], I showcased factual insight on one of the most prolific writers of musical theatre and infused it with comedy in order to educate and create appeal for Stephen Sondheim’s works, especially those lesser known, to a wider theatrical audience. -

Anthony De Mare, Piano Re-Imagining Sondheim from the Piano

Sunday, November 5, 201 7, 7pm Hertz Hall Anthony de Mare, piano Re-Imagining Sondheim from the Piano PROGRAM (all works based on material by Stephen Sondheim) andy akiHo into the Woods (2013) (Into the Woods ) William boLcoM a Little Night fughetta (2010) (after “anyone can Whistle” & “Send in the clowns”) ricky ian GorDoN Every Day a Little Death (2008/2010) (A Little Night Music ) annie GoSfiELD a bowler Hat (2011) (Pacific Overtures ) Mason batES very Put together (2012) (after “Putting it together” from Sunday in the Park with George ) Steve rEicH finishing the Hat –two Pianos (2010) (Sunday in the Park with George ) Gabriel kaHaNE being alive (2011) (Company ) Ethan ivErSoN Send in the clowns (2011) (A Little Night Music ) Wynton MarSaLiS that old Piano roll (2014) (Follies ) thomas NEWMaN Not While i’m around (2012) (Sweeney Todd ) Duncan SHEik Johanna in Space (2014) (after “Johanna” from Sweeney Todd ) Jake HEGGiE i’m Excited. No You’re Not. (2010) (after “a Weekend in the country” from A Little Night Music ) All pieces were commissioned expressly for the Liaisons Project, Rachel Colbert and Anthony de Mare, producers. Cal Performances’ 2017 –18 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 27 PROGRAM NOTES ike many of us, i have long held in highest COMPOSER COMMENTS esteem the work of Stephen Sondheim, Lwhose fearless eclecticism has emboldened Andy Akiho: “ the first time i listened to it i loved many a musical risk-taker. over the years, i often the concept of Into the Woods —being lost in and found myself imagining how the familiar and confused by the woods, and the consistent and beloved songs of the Sondheim canon would driving rhythms of the opening prologue.