Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LD3928-A23-1962-1963.Pdf

MUSICAL PROGRAM of William Neal Reynolds Coliseum June 1. 1963 CARILLON CONCERT: 9:30 A.M. The Memorial Tower Ralph W. Daniel, Carillonneur NORTH CAROLINA STATE COLLEGE BAND CONCERT: 9:45 A.M. March King Cotton Sousa Orlando Palandrino t ___________ Haydn Farandole, from L‘Arlcsiennc Suite __________________________________________________ ................... Bizet Zueignung ‘‘‘‘‘‘ _________ R. Strauss Pictures at an Exhibition ................................................. ................ Moussorgsky The Hut of Baba-Yaga Great Gate of Kiev 10:15 AM. MarchPROCESSIONAL:Processional . Grundman RECESSIONAL: University Grand March Goldman NORTH CAROLINA STATE COLLEGE BAND J. Perry Watson, Director of Music Donald B. Adcock, Assistant Director of Music COMMENCEMENT PROGRAM Exercises of William Neal Reynolds Coliseum June 1, 1965 PROCESSIONAL 10:15 A.M. Donald B. Adcock Conductor, Carolina State College Band seatedThe audienceduring istherequestedprocessionalto remain PRESIDING John T. Caldwell Chancellor, North Carolina College WELCOME INVOCATION ...................................................................... Oscar B. Wooldridge Coordinator of Religious Aflairs North Carolina College ADDRESS David E. Bell Director, Agency for International Development United States Department of State CONFERRING OF DEGREES John T. Caldwell Chancellor, North Carolina State College Harry C. Kelly Dean of the Faculty Candidata for baccalaureate degrees presented bydegreesDeanspresentedof Schools.by theCandidatesDean of forthe advancedGraduate sentedSchool. -

Get Kindle ~ I Got the Show Right Here: the Amazing, True Story of How an Obscure Brooklyn Horn Player Became the Last Great

RBGQFFMVTXAK > PDF I Got the Show Right Here: The Amazing, True Story of How... I Got th e Sh ow Righ t Here: Th e A mazing, True Story of How an Obscure Brooklyn Horn Player Became th e Last Great Broadway Sh owman Filesize: 5.29 MB Reviews Very helpful to all of class of folks. This is certainly for all who statte there had not been a worthy of studying. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Jayda Lehner Jr.) DISCLAIMER | DMCA QV3DHDPSTJWM ~ Kindle ^ I Got the Show Right Here: The Amazing, True Story of How... I GOT THE SHOW RIGHT HERE: THE AMAZING, TRUE STORY OF HOW AN OBSCURE BROOKLYN HORN PLAYER BECAME THE LAST GREAT BROADWAY SHOWMAN Audible Studios on Brilliance, 2016. CD-Audio. Condition: New. Unabridged. Language: English . Brand New. Guys Dolls The Boyfriend How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying Can-Can These are just a few of the many Broadway shows produced by the legendary Cy Feuer, who, in partnership with the late Ernest H. Martin, brought to life many of America s most enduring musicals. Cy Feuer was at the center of these creations, as well as the films based on two of Broadway s most exceptional musicals, Cabaret and A Chorus Line. He was the man in charge, the one responsible for putting everything together, and almost more important for holding it together. Now, at age 92, as Cy Feuer looks back on the remarkable career he had on Broadway and in Hollywood, the stories he has to tell of the people he worked with are fabulously rich and entertaining. -

At Powell Hall

GROUPS WELCOME AT POWELL HALL 2017 2018 GROUP SALES GUIDE SEASON slso.org/groupsI 314-286-4155 GROUPS ENJOY FIVE-STAR BENEFITS PERSONALIZED SERVICE Receive one-on-one, personalized service for all your group needs. From seat selection to performance suggestions to local restaurant recommendations, we’re ready to assist with planning your next visit to Powell Hall! SAVINGS Enjoy up to 20%* o the single ticket price when you bring 10 or more people. FREE BUS PARKING Parking, map and transportation information included with all group orders. PRIORITY SEATING Get the best seats for a great price! Group reservations can be made in advance of OUR FAMILY IS YOUR FAMILY public on-sale dates. PRE-CONCERT CONVERSATIONS Whether you’ve been part of the musical tradition or joining us for the first time, Even great music-making profits from an introduction. Enjoy FREE Pre-Concert we welcome you and your neighbors, friends, colleagues or students to experience Conversations before every SLSO classical concert. Music Director David Robertson the incomparable Musical Spirit of the second oldest orchestra in the country, and our guest artists participate in many of these conversations. your St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, in our beloved home of Powell Hall. Bring your group of 10 or more and save up to 20%. These musical oerings are just the start SPONSORED BY of making memories with us this upcoming season! THE SLSO SPECIALIZES IN HOSTING GROUPS: ENHANCE YOUR EXPERIENCE Corporations Employee Outings Schools + Universities Social + Professional Clubs SHUTTLE SERVICE Attraction + Performance Tour Groups Convenient transportation from West County is available for our Friday morning Senior + Youth Groups Coee Concerts. -

American Music Research Center Journal

AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER JOURNAL Volume 19 2010 Paul Laird, Guest Co-editor Graham Wood, Guest Co-editor Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado Boulder THE AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Mary Dominic Ray, O.P. (1913–1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music William S. Farley, Research Assistant, 2009–2010 K. Dawn Grapes, Research Assistant, 2009–2011 EDITORIAL BOARD C. F. Alan Cass Kip Lornell Susan Cook Portia Maultsby Robert R. Fink Tom C. Owens William Kearns Katherine Preston Karl Kroeger Jessica Sternfeld Paul Laird Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Victoria Lindsay Levine Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25.00 per issue ($28.00 outside the U.S. and Canada). Please address all inquiries to Lisa Bailey, American Music Research Center, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. E-mail: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISSN 1058-3572 © 2010 by the Board of Regents of the University of Colorado INFORMATION FOR AUTHORS The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing articles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and pro- posals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (excluding notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, University of Colorado Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. -

West Side Story

West Side Story West Side Story is an American musical with a book rary musical adaptation of Romeo and Juliet . He prpro-o- byby Arthur Laurents, mmususiic bbyy Leonard Bernstein,, posed that the plot focus on the conflict between an Irish libretto/lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, and conception and Catholic family and a Jewish family living on the Lower choreography byby Jerome Robbins..[1] It was inspired by East Side ofof Manhattan,,[6] during the Easter–Passover William Shakespeare's play Romeo and Juliet .. season. The girl has survivvived the Holocaust and emi- The story is set in the Upper West Side neighborhood grated from Israel; the conflict was to be centered around in New York City in the mid-1950s, an ethnic, blue- anti-Semitism of the Catholic “Jets” towards the Jewish “Emeralds” (a name that made its way into the script as collar ne neighighborhood. (In the early 1960s much of thethe [7] neineighborhood would be clecleared in anan urban renewal a reference). Eager to write his first musical, Laurents project for the Lincoln Center, changing the neighbor- immediately agreed. Bernstein wanted to present the ma- hood’s character.)[2][3] The musical explores the rivalry terial in operatic form, but Robbins and Laurents resisted between the Jets and the Sharks, two teenage street gangs the suggestion. They described the project as “lyric the- of different ethnic backgrounds. The members of the ater”, and Laurents wrote a first draft he called East Side Sharks, from Puerto Rico, are taunted by the Jets, a Story. Only after he completed it did the group realize it white gang.[4] The young protagonist, Tony, a former was little more than a musicalization of themes that had member of the Jets and best friend of the gang leader, alreadybeencoveredinin plaplaysys liklikee Abie’s Irish Rose. -

Building the Future One Play at a Time

College of Arts & Sciences Alumni Association · Winter 2008-09 IU Department of Theatre and Drama Lee Norvelle Theatre and Drama Center Membership matters. This publication is paid for in part by dues-paying members of the Indiana University Alumni Association. Building the future one play at a time his year, Indiana University celebrates its 75th season of plays, Ttracing its formal commitment to artistic and academic excellence back to Oct. 10, 1933, when, under the direction of Professor Lee Norvelle, the University Theatre presented The First Mrs. Frazer. Theatre has been part of campus life since the 1880s, when various student groups were performing plays on the Bloomington campus. During that period, and for years to come, theatre on the IU campus varied wildly in performance quality and produc- tion standards. In 1915, the Department of English offered the first theatre course, The Staging of The first production of the first season, The First Mrs. Fraser, opened in 1933 and Plays. featured Catherine Feltus, who went on to a professional acting career as Catherine (continued on page 2) Craig. In 1940, she married actor Robert Preston. WANTED: Your stories! Did one professor or mentor have a lasting impact on you? Did you fall into the pit at the University Theatre? Did you make it to Broadway (not just to see a show)? Did your theatre training play a part in help- ing to achieve your career goals? Got GREAT IU photos? The Department of Theatre and Drama is collecting stories and pictures from alumni, faculty, and staff. Your story will be compiled in our research archives to be treasured by students, alumni, and anyone who loves IU theatre for generations to come. -

Mousical Trivia

Level I: Name the classic Broadway musicals represented in these illustrations from THE GREAT AMERICAN MOUSICAL. Level II: Identify the song and the character(s) performing each one. Level III: Name the show's creators, the year the show originally opened, the theatre it opened in, and the original stars. a.) b.) e.) d.) c.) BONUS QUESTION: Can you name the choreographer Pippin the intern is paying tribute to on the cover of the book? ANSWERS Level I: Name the classic Broadway musicals represented in these illustrations from THE GREAT AMERICAN MOUSICAL. Level II: Identify the song and the character(s) performing each one. Level III: Name the show's creators, the year the show originally opened, the theatre it opened in, and the original stars. a.) d.) Level I: The King and I Level I: Fiddler on the Roof Level II: "Getting to Know You", Anna Leonowens, Royal Wives Level II: “If I Were a Rich Man”, Tevye and Royal Children Level III: Book by Joseph Stein; Based on stories by Sholom Aleichem; Level III: Music by Richard Rodgers; Lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein Music by Jerry Bock; Lyrics by Sheldon Harnick. 1964, Imperial Theatre. II; Book by Oscar Hammerstein II; Based on the novel "Anna and Zero Mostel & Beatrice Arthur the King of Siam" by Margaret Landon. 1951, St. James Theatre. Yul Brynner & Gertrude Lawrence b.) e.) Level I: My Fair Lady Level I: Hello, Dolly! Level II: “Wouldn't It Be Loverly?”, Eliza Doolittle and the Cockneys Level II: “Hello, Dolly!”, Mrs. Dolly Gallagher Levi, Rudolph, Waiters and Level III: Book by Alan Jay Lerner; Lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner; Music by Cooks Frederick Loewe; Adapted from "Pygmalion" by George Bernard Shaw. -

West Side Story

The United States Air Force Academy Bluebards Theatre Troupe Credits Proudly Presents Officer in Charge Lt Col Michelle Ruehl Master Carpenter Jandy Viloria Audio Technician Stan Sakamoto WEST Stage Crew RATTEX Dramaturg Dr. Marc Napolitano SIDE Support Team Flute/piccolo Erica Drakes STORY Bassoon Micaela Cuneo Based on a Conception of Trombone Sam Voss JEROME ROBBINS Violin Jared Helm French Horn Claire Badger Trumpet Josiah Savoie Trombone Braxton Sesler Percussion Matt Fleckenstein Musicians Piano Megan Getlinger Music by Lyrics by Trumpet Sean Castillo Clarinet Rose Bruns Trumpet Tom McCurdy Violin Kat Kowar Violin Matt Meno Entire Original Production Violin Nishanth Kalavakolanu Book by Directed and Choreographed by Bluebards offers its thanks to DFENG, RATTEX, and the Falcon Theater Founda- tion; without their support, this production would not have been possible. The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production12 is strictly prohibited. 1 Who’s Who in the Cast and Crew “WEST SIDE STORY” not sing or dance, he decided to try out for the spring musical! After Based on a Conception of JEROME ROBBINS taking a year off to search the moon for the secret to great singing and dancing, Kevin has returned to Bluebards (unfortunately, people on the moon dance differently than the people of Earth). He is an avid reader who enjoys nerding-out with fellow nerds about the nerdiest subjects. Book by ARTHUR LAURENTS Kevin would like to thank the cast/crew, with a special nod to Lt Col Music by LEONARD BERNSTEIN Ruehl for ensuring USAFA’s drama nerds have a home in Bluebards. -

December 8-10 & 14-17, 2017

Marietta’s Community Theater 2017 Pulitzer Prize-Winning Season Book by Music and Lyrics by Abe Burrows, Frank Loesser Jack Weinstock & Willie Gilbert Based on How to Succeed in Business without Really Trying by Shepherd Mead December 8-10 & 14-17, 2017 2017 DIAMOND LEVEL PATRON SUPPORT GIVEN IN LOVING MEMORY OF Gene Eater Herchelroth BY THE EATER AND OVERLANDER FAMILIES SEASON BUSINESS SPONSORS American Legion Post 466 Union Community Bank @ssc_theater (717) 426-1277 264 West Market Street, P.O. Box 23 @susquehannastageco Marietta, Pennsylvania 17547 Facebook.com/susquehannastageco www.susquehannastageco.com (717) 426-1277 264 West Market Street, P.O. Box 23 Marietta, Pennsylvania 17547 www.susquehannastageco.com Box Office Hours Jim Johnson Mon. and Wed. 7:00 - 9:00 p.m. Artistic Director Saturdays 9:00 - 11:00 a.m. (One month prior to show opening, and continu- Sylvia Garner ing through the run of each production) The Box Office is open one hour Administrative Director before show time on performance dates. Jason Spickler Business Manager Main Stage Performance Times Thursday through Saturday Evening performances at 8:00 p.m. Sunday Matinee performances at 2017-2018 2:00 p.m. Board of Directors Audience Notes: • Unauthorized use of flash Stephen Bair cameras and recording devices Chairman is strictly prohibited. • For the consideration of fellow Curt Elledge audience members, please turn Vice Chairman off all electronic devices. In addition to being a distraction, Nichole Garner they can interfere with the lighting and sound controls. Secretary • Patrons are prohibited from Cynthia Hassinger smoking inside the theater, • Aisles are frequently used for Treasurer actors’ entrances and exits. -

Guys and Dolls Short

media contact: erica lewis-finein brightbutterfly pr brightbutterfly[at]hotmail.com BERKELEY PLAYHOUSE CONTINUES FIFTH SEASON WITH “GUYS AND DOLLS” March 21-April 28, 2013 Music and Lyrics by Frank Loesser Book by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows Based on “The Idyll of Miss Sarah Brown” and “Blood Pressure” by Damon Runyon Berkeley, CA (February 11, 2013) – Berkeley Playhouse continues its fifth season with the Tony Award- winning GUYS AND DOLLS. Jon Tracy (Berkeley Playhouse, Aurora Theatre Company, Shotgun Players, San Francisco Playhouse, Magic Theatre) helms this musical from the Golden Age of Broadway, featuring a cast of 22, and choreography by Chris Black (Berkeley Playhouse, Aurora Theatre Company). GUYS AND DOLLS plays March 21 through April 28 (Press opening: March 23) at the Julia Morgan Theatre in Berkeley. For tickets ($17-60) and more information, the public may visit berkeleyplayhouse.org or call 510-845-8542x351. This oddball romantic comedy, about which Newsweek declared, “This is why Broadway was born!,” finds gambler Nathan Detroit desperate for money to pay for his floating crap game. To seed his opportunity, he bets fellow gambler Sky Masterson a thousand dollars that Sky will not be able to make the next girl he sees, Save a Soul Mission do-gooder Sarah Brown, fall in love with him. While Sky eventually convinces Sarah to be his girl, Nathan fights his own battles with Adelaide, his fiancé of 14 years. Often called “the perfect musical,” GUYS AND DOLLS features such bright and brassy songs as “A Bushel and a Peck” “Luck Be a Lady,” and “Adelaide's Lament.” GUYS AND DOLLS premiered on Broadway in 1950; directed by renowned playwright and director George S. -

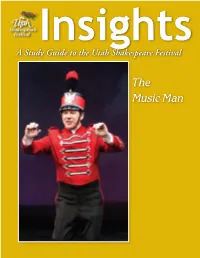

The Music Man the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival The Music Man The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. Insights is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2011, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print Insights, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Brian Vaughn as Professor Harold Hill in The Music Man, 2011. Contents Information on the Play Synopsis 4 CharactersThe Music Man 5 About the Playwrights 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play Making Yesterday Worth Remembering 8 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Synopsis: The Music Man In July 1912, fast-talking traveling salesman “Professor” Harold Hill comes to River City, Iowa, a town hesitant of letting strangers in, especially ones trying to sell something. Harold calls himself a music professor, selling band instruments, uniforms, and the idea of starting a boy’s band with the local youth. -

WEST SIDE STORY.Pages

2015-2016 SEASON 2015-2016 SEASON Teacher Resource Guide ! and Lesson Plan Activities Featuring general information about our production along with some creative activities Tickets: thalian.org! !to help you make connections to your classroom curriculum before and after the show. ! 910-251-1788 ! The production and accompanying activities ! address North Carolina Essential Standards in Theatre or! Arts, Goal A.1: Analyze literary texts & performances. ! CAC box office 910-341-7860 Look! for this symbol for other curriculum connections. West Side Story! ! Book by: Arthur Laurents Music by: Leonard Bernstein Lyrics by: Stephen Sondheim ! ! Based on Conception of: Jerome Robbins! Based on Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet! October 9-11! and 16-18! ! 7:00 PM Thursday - Saturday! and 3:00PM Saturday & Sunday! Hannah Block Historic USO! / Community Arts Center! Second Street Stage 120 South 2nd Street (Corner of Orange) Resource! About this Teaching Resource! This Teaching Resource is designed to help build new partnerships that employ theatre and the Summery:! arts to address some of today’s pressing issues such as youth violence, bullying, gangs, ! interracial tensions, youth-police relations and cultural conflict. This guide provides a perfect ! ! opportunity to partner with law enforcement, schools, youth-based organizations, and community Page 2! groups to develop new approaches to gang prevention.! About the Creative Team, ! Summery of the Musical! About the Musical & Its Relevance for Today! ! Marking its 58th anniversary, West Side Story provides the backdrop to an exploration! Page 3! of youth gangs, youth-police relationships, prejudice and the romance of two young people caught Character & Story Parallels of in a violent cross-cultural struggle.The electrifying music of Leonard Bernstein and the prophetic West Side Story and lyrics of Stephen Sondheim hauntingly paint a picture as relevant today as it was more than 58 Romeo & Juliet ! years ago.