Sondheim's Didactic Nature and Its Effects On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Initiative Jka Peer - Reviewed Journal of Music

VOL. 01 NO. 01 APRIL 2018 MUSIC INITIATIVE JKA PEER - REVIEWED JOURNAL OF MUSIC PUBLISHED,PRINTED & OWNED BY HIGHER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT, J&K CIVIL SECRETARIAT, JAMMU/SRINAGAR,J&K CONTACT NO.S: 01912542880,01942506062 www.jkhighereducation.nic.in EDITOR DR. ASGAR HASSAN SAMOON (IAS) PRINCIPAL SECRETARY HIGHER EDUCATION GOVT. OF JAMMU & KASHMIR YOOR HIGHER EDUCATION,J&K NOT FOR SALE COVER DESIGN: NAUSHAD H GA JK MUSIC INITIATIVE A PEER - REVIEWED JOURNAL OF MUSIC INSTRUCTION TO CONTRIBUTORS A soft copy of the manuscript should be submitted to the Editor of the journal in Microsoft Word le format. All the manuscripts will be blindly reviewed and published after referee's comments and nally after Editor's acceptance. To avoid delay in publication process, the papers will not be sent back to the corresponding author for proof reading. It is therefore the responsibility of the authors to send good quality papers in strict compliance with the journal guidelines. JK Music Initiative is a quarterly publication of MANUSCRIPT GUIDELINES Higher Education Department, Authors preparing submissions are asked to read and follow these guidelines strictly: Govt. of Jammu and Kashmir (JKHED). Length All manuscripts published herein represent Research papers should be between 3000- 6000 words long including notes, bibliography and captions to the opinion of the authors and do not reect the ofcial policy illustrations. Manuscripts must be typed in double space throughout including abstract, text, references, tables, and gures. of JKHED or institution with which the authors are afliated unless this is clearly specied. Individual authors Format are responsible for the originality and genuineness of the work Documents should be produced in MS Word, using a single font for text and headings, left hand justication only and no embedded formatting of capitals, spacing etc. -

Sondheim's Putting It Together Gathers More Than 30 Songs From

CSFINEARTSCENTER.ORG Contact: Dori Mitchell, Director of Communications 719.477.4312; [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Sondheim’s Putting It Together gathers more than 30 songs from award‐winning works COLORADO SPRINGS (Aug. 10, 2015) This musical revue showcases the songs of Stephen Sondheim, America’s most‐awarded living musical theatre composer. Featuring nearly 30 Sondheim songs from at least a dozen of his award‐winning shows (including A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Into the Woods, Sweeney Todd, Company and Follies), this one‐of‐a‐kind compilation celebrates Sondheim’s incomparable career in musical theatre. “Stephen Sondheim has written some of the best musical theatre of the last 50 years,” says Performing Arts Director Scott RC Levy, “and will go down in history as one of the most important American composers of the 20th Century. The FAC has a strong history of producing his work, and when thinking of which show of his to do next, I thought of this piece, which features so much of his beautiful music from pieces throughout his career.” The FAC production features an all‐star cast, including Max Ferguson, Sally Hybl, Jordan Leigh, Scott RC Levy and Mackenzie Sherburne. Nathan Halvorson directs and choreographs. Sondheim has won the Kennedy Center Lifetime Achievement Award, a Pulitzer Prize, an Academy Award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, eight Grammy Awards, 12 Tony Awards, 16 Drama Desk Awards and six Olivier Awards. The FAC has produced 10 Sondheim works, including Into the Woods, Funny Thing Happened…, Assassins and Sweeney Todd since 1989. -

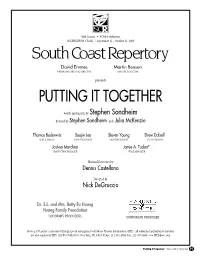

Putting It Together

46th Season • 437th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / September 11 - October 11, 2009 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing ArtiStic director ArtiStic director presents PUTTING IT TOGETHER words and music by Stephen Sondheim devised by Stephen Sondheim and Julia McKenzie Thomas Buderwitz Soojin Lee Steven Young Drew Dalzell Scenic deSign coStume deSign Lighting deSign Sound deSign Joshua Marchesi Jamie A. Tucker* Production mAnAger StAge mAnAger musical direction by Dennis Castellano directed by Nick DeGruccio Dr. S.L. and Mrs. Betty Eu Huang Huang Family Foundation honorAry ProducerS corPorAte Producer Putting It Together is presented through special arrangement with music theatre international (mti). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by mti. 421 West 54th Street, new york, ny 10019; Phone: 212-541-4684 Fax: 212-397-4684; www.mtiShows.com Putting It Together• SOUTH COA S T REPE R TO R Y P1 THE CAST (in order of appearance) Matt McGrath* Harry Groener* Niki Scalera* Dan Callaway* Mary Gordon Murray* MUSICIANS Dennis Castellano (conductor/keyboards), John Glaudini (synthesizer), John Reilly (woodwinds), Louis Allee (percussion) SETTING A New York penthouse apartment. Now. LENGTH Approximately two hours including one 15-minute intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting ................................................................................ Joanne DeNaut, CSA Dramaturg .......................................................................... Linda Sullivan Baity Assistant Stage Manager ............................................................. -

Solomon and Sinatra: the Song of Songs and Romance in the Church Robert Case a Sunday School Class Faith Presbyterian Church Tacoma, Washington 2016

1 Solomon and Sinatra: The Song of Songs and Romance in the Church Robert Case A Sunday School Class Faith Presbyterian Church Tacoma, Washington 2016 Part 3 There are a multitude of biblical themes expressed by non-believing Jewish songwriters in the American Songbook, but one fine example for our purposes in this class is the theme of: no Sex before marriage “Love and Marriage” In 1955 Jimmy Van Heusen (a Methodist) with Jewish lyricist Sammy Cahn wrote “Love and Marriage” which was introduced (ironically) by Frank Sinatra in the television production of Thornton Wilder's Our Town. It is the biggest hit to ever come out of a television special. In 1956, the song, "Love and Marriage" won the Emmy Award for Best Musical Contribution from the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. The Cahn inspired clever lyrics euphemistically call “sex” “love” and claim that mom told dad you can’t have sex (“love”) without marriage. The song was used as the theme song for the long-running (1987–97) FOX television sitcom Married... with Children. Additionally, the song has been used in several national commercial campaigns. “Love and marriage, love and marriage, go together like a horse and carriage. This I tell you brother you can't have one without the other. Love and marriage, love and marriage, it's an institute you can't disparage. Ask the local gentry and they will say it's elementary. Try, try, try to separate them it's an illusion Try, try, try, and you will only come to this conclusion. -

Determining Stephen Sondheim's

“I’VE A VOICE, I’VE A VOICE”: DETERMINING STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE THROUGH A MUSIC-THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF HIS THEATER WORKS BY ©2011 PETER CHARLES LANDIS PURIN Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ___________________________ Chairperson Dr. Scott Murphy ___________________________ Dr. Deron McGee ___________________________ Dr. Paul Laird ___________________________ Dr. John Staniunas ___________________________ Dr. William Everett Date Defended: August 29, 2011 ii The Dissertation Committee for PETER PURIN Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “I’VE A VOICE, I’VE A VOICE”: DETERMINING STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE THROUGH A MUSIC-THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF HIS THEATER WORKS ___________________________ Chairperson Dr. Scott Murphy Date approved: August 29, 2011 iii Abstract This dissertation offers a music-theoretic analysis of the musical style of Stephen Sondheim, as surveyed through his fourteen musicals that have appeared on Broadway. The analysis begins with dramatic concerns, where musico-dramatic intensity analysis graphs show the relationship between music and drama, and how one may affect the interpretation of events in the other. These graphs also show hierarchical recursion in both music and drama. The focus of the analysis then switches to how Sondheim uses traditional accompaniment schemata, but also stretches the schemata into patterns that are distinctly of his voice; particularly in the use of the waltz in four, developing accompaniment, and emerging meter. Sondheim shows his harmonic voice in how he juxtaposes treble and bass lines, creating diagonal dissonances. -

INTO the WOODS Stephen Sondheim (Music and Lyrics) and James Lapine (Book) Directed by Susi Damilano Music Director: Dave Dobrusky Choreography: Kimberly Richards

Press Release For immediate release May 2014 [email protected] Download Hi Res photos here INTO THE WOODS Stephen Sondheim (music and lyrics) and James Lapine (book) Directed by Susi Damilano Music Director: Dave Dobrusky Choreography: Kimberly Richards June 24th to September 6th Previews June 24 – June 27 at 8pm Tuesdays through Thursdays at 7pm, Fridays and Saturdays at 8pm Saturdays at 3pm and Sundays at 2pm (except 6/29) PRESS OPENING: Saturday, June 28th at 8pm San Francisco, CA (May 2014) – San Francisco Playhouse (Artistic Director Bill English & Producing Director Susi Damilano) concludes its provocative eleventh season with Into the Woods by Stephen Sondheim (music and lyrics) and James Lapine (book). What happens after “happily ever after?” Fractured fairy tales of a darker hue provide the context for Into the Woods, which deconstructs the Brothers Grimm by way of “The Twilight Zone.” While the faces and names are familiar, Cinderella, Rapunzel, Little Red Riding Hood, Jack in the Beanstalk and company inhabit a sylvan neighborhood in which witches and bakers are next-door neighbors, handsome princes from once-parallel fables are competitive (and equally vain) brothers, and all the stories intersect through unexpected new plot twists. Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s beloved musical intertwines classic fairytales with a contemporary edge to tell stories of wishes granted and “the price” paid. Susi Damilano (Director), Dave Dobrusky (Music Director) and Kimberly Richards (Choreographer) will team up to bring a fresh twist to this familiar tale by adding a time-travelling boy, Ian DeVaynes to the Bay Area cast that features: Louis Parnell* (Narrator), Safiya Fredericks* (Witch), El Beh (Baker’s Wife), Keith Pinto* (Baker), Tim Homsley* (Jack), Joan Mankin* (Jack’s Mom), Monique Hafen* (Cinderella), Becka Fink (Cinderella’s Stepmom), identical twins, Lily and Michelle Drexler (Cinderella’s Stepsisters), Noelani Neal (Rapunzel), Corinne Proctor (Red), Ryan McCrary and Jeffrey Adams (Princes/Wolves) and John Paul Gonzales (Steward). -

Broadway 1 a (1893-1927) BROADWAY and the AMERICAN DREAM

EPISODE ONE Give My Regards to Broadway 1 A (1893-1927) BROADWAY AND THE AMERICAN DREAM In the 1890s, immigrants from all over the world came to the great ports of America like New York City to seek their fortune and freedom. As they developed their own neighborhoods and ethnic enclaves, some of the new arrivals took advantage of the stage to offer ethnic comedy, dance and song to their fellow group members as a much-needed escape from the hardships of daily life. Gradually, the immigrants adopted the characteristics and values of their new country instead, and their performances reflected this assimilation. “Irving Berlin has no place in American music — he is American music.” —composer Jerome Kern My New York (excerpt) Every nation, it seems, Sailed across with their dreams To my New York. Every color and race Found a comfortable place In my New York. The Dutchmen bought Manhattan R Island for a flask of booze, E V L U C Then sold controlling interest to Irving Berlin was born Israel Baline in a small Russian village in the Irish and the Jews – 1888; in 1893 he emigrated to this country and settled in the Lower East Side of And what chance has a Jones New York City. He began his career as a street singer and later turned to With the Cohens and Malones songwriting. In 1912, he wrote the words and music to “Alexander’s Ragtime In my New York? Band,” the biggest hit of its day. Among other hits, he wrote “Oh, How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning,” “What’ll I Do?,” “There’s No Business Like —Irving Berlin, 1927 Show Business,” “Easter Parade,” and the patriotic “God Bless America,” in addition to shows like Annie Get Your Gun. -

Educating About the Works of Stephen Sondheim Through Parody

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020- 2020 How Artists Can Capture Us: Educating About the Works of Stephen Sondheim Through Parody Jarrett Poore University of Central Florida Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020- by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Poore, Jarrett, "How Artists Can Capture Us: Educating About the Works of Stephen Sondheim Through Parody" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020-. 117. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020/117 HOW ARTISTS CAN CAPTURE US: EDUCATING ABOUT THE WORKS OF STEPHEN SONDHEIM THROUGH PARODY By JARRETT POORE B.F.A, University of Central Florida 2017 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Theatre in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2020 © Jarrett Mark Poore 2020 ii ABSTRACT This thesis examined the modern renaissance man and his relationship between musical theatre history and parody; it examined how the modern artist created, produced, and facilitated an original parody in which humor can both influence and enhance an individual’s interest in the art form. In the creation and production of The Complete Works of Stephen Sondheim [abridged], I showcased factual insight on one of the most prolific writers of musical theatre and infused it with comedy in order to educate and create appeal for Stephen Sondheim’s works, especially those lesser known, to a wider theatrical audience. -

A New Dawn for Hair by Richard Zoglin

Back to Article Click to Print Thursday, Jul. 31, 2008 A New Dawn for Hair By Richard Zoglin I never saw the original production of Hair, but I did catch the show a couple of years after its 1968 Broadway debut, when the touring company came to San Francisco. I was a student at Berkeley, and I would occasionally take a break from dodging tear gas in Sproul Plaza to usher for plays in the city. It was a good deal: students could spend half an hour helping fat cats find their way to their orchestra seats and, after the curtain went up, take any empty seat for free. Except that the night I saw Hair, the house was full, so the ushers had to sit on the aisle steps in the balcony. Which turned out to be the perfect way to experience the celebrated "tribal rock musical" that brought the communal spirit of the '60s youth culture to Broadway for the first time. It was the greatest night of my theater life. Well, maybe not quite. But allow a baby boomer his memories. (To be honest, I probably didn't call them fat cats either.) And allow Hair--or so even some professed fans of the show have pleaded--to remain in the mists of '60s nostalgia. After a flop 1977 Broadway revival and a not-much-more-successful 1979 movie version directed by Milos Forman, the feeling seemed to harden that the Age of Aquarius was over and trying to bring it back would look hopelessly out of touch, even silly, in this cynical new millennium. -

Anthony De Mare, Piano Re-Imagining Sondheim from the Piano

Sunday, November 5, 201 7, 7pm Hertz Hall Anthony de Mare, piano Re-Imagining Sondheim from the Piano PROGRAM (all works based on material by Stephen Sondheim) andy akiHo into the Woods (2013) (Into the Woods ) William boLcoM a Little Night fughetta (2010) (after “anyone can Whistle” & “Send in the clowns”) ricky ian GorDoN Every Day a Little Death (2008/2010) (A Little Night Music ) annie GoSfiELD a bowler Hat (2011) (Pacific Overtures ) Mason batES very Put together (2012) (after “Putting it together” from Sunday in the Park with George ) Steve rEicH finishing the Hat –two Pianos (2010) (Sunday in the Park with George ) Gabriel kaHaNE being alive (2011) (Company ) Ethan ivErSoN Send in the clowns (2011) (A Little Night Music ) Wynton MarSaLiS that old Piano roll (2014) (Follies ) thomas NEWMaN Not While i’m around (2012) (Sweeney Todd ) Duncan SHEik Johanna in Space (2014) (after “Johanna” from Sweeney Todd ) Jake HEGGiE i’m Excited. No You’re Not. (2010) (after “a Weekend in the country” from A Little Night Music ) All pieces were commissioned expressly for the Liaisons Project, Rachel Colbert and Anthony de Mare, producers. Cal Performances’ 2017 –18 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. 27 PROGRAM NOTES ike many of us, i have long held in highest COMPOSER COMMENTS esteem the work of Stephen Sondheim, Lwhose fearless eclecticism has emboldened Andy Akiho: “ the first time i listened to it i loved many a musical risk-taker. over the years, i often the concept of Into the Woods —being lost in and found myself imagining how the familiar and confused by the woods, and the consistent and beloved songs of the Sondheim canon would driving rhythms of the opening prologue. -

The King and I

The King and I - A Musical by composer Richard Rodgers & dramatist Oscar Hammerstein II WaCPAC Auditions - 9/21 (2 pm), 23, 24, & 26 (7 pm) Callbacks: 9/30 (7 pm) Performances dates: January 4, 5, 10, 11, & 12, 2020 This is an intergenerational musical so all ages are encouraged to audition. During the auditions, you will be asked to do a cold-read from a script for the artistic director. This means you will likely be given a short time (after you arrive for audition) to glance over a section of script and read with others also auditioning. We may have something different for young non-readers for this part. For character names, part descriptions and vocal ranges, please check this link online: https://studylib.net/doc/7223371/the-attached-character-list. For the musical part of the audition, please sing a verse and chorus of a song. We would prefer a show tune, similar in style to The King and I for those that are teens and older. For younger ones, please have them sing a familiar tune. Examples of songs that could be used: Teens and Adults: “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’” - Oklahoma! “Edelweiss” - The Sound of Music “Almost Like Being in Love” - Brigadoon “I Could’ve Danced All Night” - My Fair Lady Younger children: “I Whistle a Happy Tune” - The King and I “Getting to Know You” - The King and I “Do, Re, Mi” - The Sound of Music “Somewhere Out There” - An American Tail (film) Mary Had a Little Lamb Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star If you would like to be considered for a singing role, even if only ever singing in a group/ensemble in the show, you must do a singing audition. -

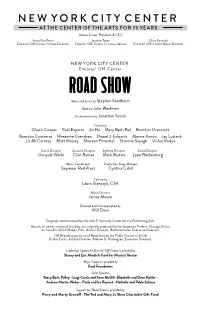

Read the Road Show Program

NEW YORK CITY CENTER AT THE CENTER OF THE ARTS FOR 75 YEARS Arlene Shuler, President & CEO Anne Kauffman Jeanine Tesori Chris Fenwick Encores! Off-Center Artistic Director Encores! Off-Center Creative Advisor Encores! Off-Center Music Director NEW YORK CITY CENTER Encores! Off-Center Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by John Weidman Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Featuring Chuck Cooper Raúl Esparza Jin Ha Mary Beth Peil Brandon Uranowitz Brandon Contreras Rheaume Crenshaw Daniel J. Edwards Marina Kondo Jay Lusteck Liz McCartney Matt Moisey Shereen Pimentel Sharone Sayegh Vishal Vaidya Scenic Designer Costume Designer Lighting Designer Sound Designer Donyale Werle Clint Ramos Mark Barton Leon Rothenberg Music Coordinator Production Stage Manager Seymour Red Press Cynthia Cahill Casting by Laura Stanczyk, CSA Music Director James Moore Directed and Choreographed by Will Davis Originally commissioned by the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Bounce, an earlier version of this play, was originally produced by the Goodman Theatre, Chicago, Illinois on June 30, 2003 (Robert Falls, Artistic Director; Roche Schulfer, Executive Director). Off-Broadway premiere of Road Show by the Public Theater in 2008 (Oskar Eustis, Artistic Director; Andrew D. Hamingson, Executive Director). Leadership Support for Encores! Off-Center is provided by Stacey and Eric Mindich Fund for Musical Theater Major Support is provided by Ford Foundation Series Sponsors Stacy Bash-Polley • Luigi Caiola and Sean McGill • Elizabeth and Dean Kehler •