Did Nicholas of Cusa Talk with Muslims? Revisiting Cusanus’ Sources for the Cribratio Alkorani and Interfaith Dialogue *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cusanus, on Learned Igorance-17Z8dxd

On Learned Ignorance Harries 1 Karsten Harries Nicholas of Cusa On Learned Ignorance Seminar Notes Fall Semester 2015 Yale University Copyright Karsten Harries On Learned Ignorance Harries 2 Contents 1. Introduction 3 Book One 2. Learned Ignorance 17 3. The Coincidence of Opposites 30 4. The Threat of Pantheism 47 5. The Power of Mathematics 61 6. Naming God 76 Book Two 7. The Shape of the Universe 90 8. Matter and Becoming 105 9. The Condition of the Earth 118 Book Three 10. The Need for Christ 131 11. Death and Resurrection 146 12. Faith and Understanding 162 13. Death, Damnation, and the Church 176 On Learned Ignorance Harries 3 1. Introduction 1 Many philosophers today have become uneasy about what philosophy has become and where it has led us. Nietzsche and Heidegger, Derrida and Rorty are just a few names. Their uneasiness mirrors widespread concern about the shape of our modern culture. As more and more begin to suspect that the road on which we have been travelling may be a dead end, attempt are made to retrace steps taken; a search begins for missed turns and for those who may have misled us. Among these Descartes has long occupied a special place as the thinker whose understanding of proper method helped found modern philosophy, science, and indeed the shape of our technological world. It is thus to be expected that attempts to question modernity, to confront it, in order perhaps to take a step beyond it, should have often taken the form of attempts to confront Descartes or Cartesian rationality. -

Nicholas of Cusa and Islam

Nicholas of Cusa and Islam Ian Christopher Levy, Rita George-Tvrtković, and Donald F. Duclow - 9789004274761 Downloaded from Brill.com10/01/2021 12:32:35PM via free access Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions Edited by Andrew Colin Gow (Edmonton, Alberta) In cooperation with Sylvia Brown (Edmonton, Alberta) Falk Eisermann (Berlin) Berndt Hamm (Erlangen) Johannes Heil (Heidelberg) Susan C. Karant-Nunn (Tucson, Arizona) Martin Kaufhold (Augsburg) Erik Kwakkel (Leiden) Jürgen Miethke (Heidelberg) Christopher Ocker (San Anselmo and Berkeley, California) Founding Editor Heiko A. Oberman † VOLUME 183 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/smrt Ian Christopher Levy, Rita George-Tvrtković, and Donald F. Duclow - 9789004274761 Downloaded from Brill.com10/01/2021 12:32:35PM via free access Nicholas of Cusa and Islam Polemic and Dialogue in the Late Middle Ages Edited by Ian Christopher Levy Rita George-Tvrtković Donald F. Duclow LEIDEN | BOSTON Ian Christopher Levy, Rita George-Tvrtković, and Donald F. Duclow - 9789004274761 Downloaded from Brill.com10/01/2021 12:32:35PM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. -

Nicholas of Cusa and Modern Philosophy

//FS2/CUP/3-PAGINATION/HRP/2-PROOFS/3B2/9780521846486C09.3D 173 [173–192] 2.5.2007 8:03AM 9 DERMOT MORAN Nicholas of Cusa and modern philosophy ‘‘Gatekeeper of the modern age’’ Nicholas of Cusa (Niklas Krebs, known as Cusanus, 1401–64), one of the most original and creative intellects of the fifteenth century,1 has been variously described as ‘‘the last great philosopher of the dying Middle Ages’’ (Alexandre Koyre´), as a ‘‘transition-thinker’’ between the medieval and modern worlds (Frederick Copleston),2 and as the ‘‘gatekeeper of the modern age’’ (Rudolf Haubst).3 He is a lone figure with no real successor although he had some influence on Copernicus, Kepler, Bruno, and, tangen- tially, on Descartes. The German Idealists showed some interest in Nicholas of Cusa but the real revival of his thought was stimulated by the neo-Kantian philosopher Ernst Cassirer (1874–1945) who called him ‘‘the first modern thinker’’ and by the existentialist Karl Jaspers.4 Cassirer compared him to Kant for his view that objects have to be understood in terms of the categories of our own thought.5 Other scholars, notably Alexandre Koyre´,6 Hans-Georg Gadamer7 Hans Blumenberg,8 Werner Beierwaltes,9 and Karsten Harries,10 all see him in a certain way as a harbinger of modernity.11 Yet his outlook is essentially conservative, aiming, as Hans Blumenberg has recognized, to maintain the medieval synthesis.12 Cusanus was a humanist scholar, Church reformer – his De concordantia catholica (On Catholic Concord, 1434) included proposals for the reform of Church and state – papal diplomat, and Catholic cardinal. -

Cna85b2317313.Pdf

THE PAINTERS OF THE SCHOOL OF FERRARA BY EDMUND G. .GARDNER, M.A. AUTHOR OF "DUKES AND POETS IN FERRARA" "SAINT CATHERINE OF SIENA" ETC LONDON : DUCKWORTH AND CO. NEW YORK : CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS I DEDICATE THIS BOOK TO FRANK ROOKE LEY PREFACE Itf the following pages I have attempted to give a brief account of the famous school of painting that originated in Ferrara about the middle of the fifteenth century, and thence not only extended its influence to the other cities that owned the sway of the House of Este, but spread over all Emilia and Romagna, produced Correggio in Parma, and even shared in the making of Raphael at Urbino. Correggio himself is not included : he is too great a figure in Italian art to be treated as merely the member of a local school ; and he has already been the subject of a separate monograph in this series. The classical volumes of Girolamo Baruffaldi are still indispensable to the student of the artistic history of Ferrara. It was, however, Morelli who first revealed the importance and significance of the Perrarese school in the evolution of Italian art ; and, although a few of his conclusions and conjectures have to be abandoned or modified in the light of later researches and dis- coveries, his work must ever remain our starting-point. vii viii PREFACE The indefatigable researches of Signor Adolfo Venturi have covered almost every phase of the subject, and it would be impossible for any writer now treating of Perrarese painting to overstate the debt that he must inevitably owe to him. -

Pál Bolberitz: the Beginnings of Hungarian Philosophy

A SZENT IS1V AN TIJDOMANYOS AKADEMIA SZEKFOGLALO ELOADASAI Uj Folyam. 2/2. szam Szerkeszti: STIRLING JANos OESSH fot.itkar PAL BOLBERITZ THE BEGINNINGS OF HUNGARIAN PHILOSOPHY (THE RECEPTION OF NICHOLAS OF CUSA IN THE WORK ,DE HOMINE" BY PETER CS6KAS LASKOI) BUDAPEST 2004 A SZENT IS1V AN TIJDOMANYOS AKADEMIA SZEKFOGLALO ELOADASAI Uj Folyam. 2/2. szam Szerkeszti: STIRLING JANos OESSH fot.itkar PAL BOLBERITZ THE BEGINNINGS OF HUNGARIAN PHILOSOPHY (THE RECEPTION OF NICHOLAS OF CUSA IN THE WORK ,DE HOMINE" BY PETER CS6KAS LASKOI) Magyarrryelven elhangzott a Matr~ar Tu:imdnyos A lwitfmia Felol1.J:lfJ3 tern11i1m 2003. novemher 25-in BUDAPEST 2004 Minden jog fenntartva, beleertve a btirminemu eljtirtissal val6 sokszorositds jogdt is © BOLBERITZ PAL 2004 KESZULT A SZENT ISTV ANTARSULAT, AZ APOSTOLI SZENTSZEK KONYVKIAOOJA NYOMDAJABAN. IGAZGATO: FARKAS OLIVER OESSH BUDAPEST, V. KOSSUTH LAJOS U. 1. PAL BOLBERITZ THE BEGINNINGS OF HUNGARIAN PHILOSOPHY (THE RECEPTION OF NICHOLAS OF CUSA IN THE WORK DE HOMINE BY PETER Cs6KAS LASK6I) The present study does not intend to get involved in the academic dispute flaring up from time to time to discuss whether there has ever been Hungarian philosophy or not. According to our view, Hungarian philosophy did, does and, hopefully, will exist, for it has its own proper ties. As it is well known, philosophy is the science inves tigating the ultimate principles and causes. It is not un common for the Hungarian spirit to examine the ultimate questions either. As expressed by the Latin phrases: pri mum vivere, -

NICHOLAS of CUSA's DEBATE with JOHN WENCK a Translation and an Appraisal of De Ignota Litteratura and Apologia Doctae Ignorantiae

NICHOLAS OF CUSA'S DEBATE WITH JOHN WENCK A Translation and an Appraisal of De Ignota Litteratura and Apologia Doctae Ignorantiae by JASPER HOPKINS THE ARTHUR J. BANNING PRESS MINNEAPOLIS The English translation of Apologia Doctae Ignorantiae is made from Nicolai de Cusa Opera Omnia, Vol. II, edited by Raymond Klibansky (Leipzig: F. Meiner, 1932). Third edition, 1988 (First edition, 1981) Copyright © 1981 by The Arthur J. Banning Press, Minneapolis, Min- nesota 55402. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 80-82908 ISBN 0-938060-40-6 458 1 A DEFENSE OF LEARNED IGNORANCE FROM ONE DISCIPLE TO ANOTHER (Apologia Doctae Ignorantiae Discipuli ad Discipulum) by NICHOLAS OF CUSA Our common teacher, master Nicholas of Cusa, now added to the Col- lege of Cardinals, once told me how well you understand the coinci- dences which he disclosed to us in the books of Learned Ignorance (presented to the Apostolic Legate)1 and in many of his other works. [He spoke of] your ardent wish to gather together everything which here and there flows from him regarding these matters. [He also re- ported] that you do not allow any of the learned men to pass by you without talking with them about this approach. [And he mentioned] that you have induced many who had despised this study to break for a short while with their long-standing habit of laboring with the Aris- totelian tradition and to give themselves over to these considerations, in the faith that something important lies hidden therein—[to give themselves] to the extent that with an inward relish they become more deeply attracted and come to realize that this approach differs from others as much as sight differs from hearing. -

Cusa Faith/Reason-Engl

PROLEGOMENA TO NICHOLAS OF CUSA’S CONCEPTION OF THE RELATIONSHIP OF FAITH TO REASON by JASPER HOPKINS © 1996 PROLEGOMENA TO NICHOLAS OF CUSA’S CONCEPTION OF THE RELATIONSHIP OF FAITH TO REASON “Ist der Weg des spekulativen Denkens, wenn dieses nicht eine ermüdende Spielerei wird, immer von einem Glauben her beschritten, von einem Glauben sei es der alten griechischen Fröm- migkeiten, sei es der asiatischen Glaubensweisen, sei es der christlichen?” —Karl Jaspers1 I Is there any such thing as the Cusan view of the relationship between faith and reason? That is, does Nicholas present us with clear concepts of fides and ratio and with a unique and consistent doctrine regarding their interconnection? If he does not, then the task before us is surely an impossible one: viz., the task of find- ing, describing, and setting in perspective a doctrine that never at all existed. For even with spectacles made of beryl stone or through the looking glass of Lewis Car- roll, we could not descry the totally nonexistent. Four lines of argument purport to show that the task before us is funda- mentally impossible. 1. First of all, it may be argued (a) that Nicholas of Cusa can have a coher- ent doctrine of faith and reason only if he has a generally coherent theory of knowl- edge and (b) that since his theory of knowledge is generally incoherent, so too must be the aforesaid doctrine, which is an intrinsic part of the theory of knowledge. Let us grant—for the sake of the argument—the disputable logic of this reasoning, and let us focus on the question of whether Nicholas does or does not have a viable gen- eral theory of knowledge. -

The Concept of Non-Duality in Śaṅkara and Cusanus

Comparative Philosophy Volume 12, No. 1 (2021): 98-110 Open Access / ISSN 2151-6014 / www.comparativephilosophy.org https://doi.org/10.31979/2151-6014(2021).120109 THE CONCEPT OF NON-DUALITY IN ŚAṄKARA AND CUSANUS JEROME KLOTZ ABSTRACT: When comparing diverse philosophical traditions, it becomes necessary to establish a common point of departure. This paper offers a comparative analysis of Advaita Vedānta Hinduism and esoteric Christianity, as represented by the two highly celebrated figures of Śaṅkara and Nicholas Cusanus, respectively. The common point of departure on which I base this comparison is the concept of “non-duality”—a concept that is fitting for at least two reasons. First, it is general enough to encompass both traditions, pervading the work of each figure, and thus allowing for a kind of “shared language.” Second, it is specific enough to identify a set of core and well-defined principles amenable to systematic study, chief among which are the notions of (1) the “Absolute” as an infinite unity that transcends all determinations (“no-thing”) and exceeds all oppositions (“not-other”), and (2) the world as an ontologically ambiguous “reflection” that simultaneously hides and manifests its meta- ontological Principle. In drawing these connections, I hope to show how the concept of non- duality provides the possibility for a mutual understanding among diverse traditions at the philosophical level. Keywords: Advaita Vedānta, metaphysics, mysticism, Nicholas Cusanus, non-duality, Śaṅkara 1. INTRODUCTION The concept of “non-duality” is not the exclusive possession of any one philosophical system. On the contrary, it can be found—mutatis mutandis—within religio- philosophical traditions the world over: from Philosophical Daoism, Mahāyāna Buddhism, and Advaita Vedānta Hinduism in the East, to Kabbalistic Judaism, esoteric Christianity, and mystical Islam in the West. -

Bologna and Its Porticoes: a Thousand Years' Pursuit of the “Common

Quart 2020, 3 PL ISSN 1896-4133 [s. 87-104] Bologna and its porticoes: a thousand years’ pursuit of the “common good” Francesca Bocchi Università di Bologna Rosa Smurra Università di Bologna Bologna from late antiquity to the early Middle Ages It is well known that Bologna boasts a remarkable architectural feature that distinguishes it from other European cities and towns1: the long sequence of façade porticoes lining most of its streets, both in the historic city centre and in parts of the suburbs. To those born in Bologna or who have lived there for many years, this distinctive characteristic seems obvious, but it did not appear by chance nor over a short time. It was the result of a long process that has its origins almost a thousand years ago, when documentary evidence shows that certain dwellings were built with porticoes and, more interestingly, these porticoes, for both private and public use, were built not on public land but on private property. In order to understand the evolution of this complex property law system, it is necessary to outline the phases of urban development, determined by political, social and economic factors, adapting the urban fabric to various needs over a long period of time spanning from the crisis of late antiquity to the 13th and 14th centuries [Fig. 1]. The Roman city of Bononia was a well laid out settlement, extending over an area of about 40 ha [Fig. 1A]. Cardines and decumani formed an orthogonal plan where archaeological research shows that the dwellings were built without porticoes2. The political and economic crisis affecting the Roman Empire from the 3rd century onwards reached both town and country: Bononia also felt it severely. -

Profiling Women in Sixteenth-Century Italian

BEAUTY, POWER, PROPAGANDA, AND CELEBRATION: PROFILING WOMEN IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY ITALIAN COMMEMORATIVE MEDALS by CHRISTINE CHIORIAN WOLKEN Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Edward Olszewski Department of Art History CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERISTY August, 2012 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Christine Chiorian Wolken _______________________________________________________ Doctor of Philosophy Candidate for the __________________________________________ degree*. Edward J. Olszewski (signed) _________________________________________________________ (Chair of the Committee) Catherine Scallen __________________________________________________________________ Jon Seydl __________________________________________________________________ Holly Witchey __________________________________________________________________ April 2, 2012 (date)_______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 1 To my children, Sofia, Juliet, and Edward 2 Table of Contents List of Images ……………………………………………………………………..….4 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………...…..12 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………...15 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………16 Chapter 1: Situating Sixteenth-Century Medals of Women: the history, production techniques and stylistic developments in the medal………...44 Chapter 2: Expressing the Link between Beauty and -

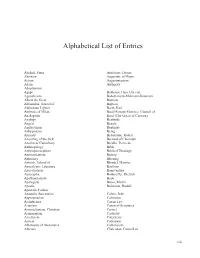

A-Z Entries List

Alphabetical List of Entries Abelard, Peter Attributes, Divine Abortion Augustine of Hippo Action Augustinianism Adam Authority Adoptionism Agape Balthasar, Hans Urs von Agnosticism Bañezianism-Molinism-Baianism Albert the Great Baptism Alexandria, School of Baptists Alphonsus Liguori Barth, Karl Ambrose of Milan Basel-Ferrara-Florence, Council of Anabaptists Basil (The Great) of Caesarea Analogy Beatitude Angels Beauty Anglicanism Beguines Anhypostasy Being Animals Bellarmine, Robert Anointing of the Sick Bernard of Clairvaux Anselm of Canterbury Bérulle, Pierre de Anthropology Bible Anthropomorphism Biblical Theology Antinomianism Bishop Antinomy Blessing Antioch, School of Blondel, Maurice Apocalyptic Literature Boethius Apocatastasis Bonaventure Apocrypha Bonhoeffer, Dietrich Apollinarianism Book Apologists Bucer, Martin Apostle Bultmann, Rudolf Apostolic Fathers Apostolic Succession Calvin, John Appropriation Calvinism Architecture Canon Law Arianism Canon of Scriptures Aristotelianism, Christian Carmel Arminianism Casuistry Asceticism Catechesis Aseitas Catharism Athanasius of Alexandria Catholicism Atheism Chalcedon, Council of xiii Alphabetical List of Entries Character Diphysitism Charisma Docetism Chartres, School of Doctor of the Church Childhood, Spiritual Dogma Choice Dogmatic Theology Christ/Christology Donatism Christ’s Consciousness Duns Scotus, John Chrysostom, John Church Ecclesiastical Discipline Church and State Ecclesiology Circumincession Ecology City Ecumenism Cleric Edwards, Jonathan Collegiality Enlightenment -

Conference Abstracts

Society for SeventeenthCentury Music A SOCIETY DEDICATED TO THE STUDY AND PERFORMANCE OF 17THCENTURY MUSIC Seventh Annual Conference University of Virginia, Charlottesville April 8-11, 1999 ABSTRACTS OF PRESENTATIONS * Index of Presentations * Program and Abstracts * Program Committee Index of Presentations * Gregory Barnett: "Chronicles of Musical Success and Failure in Late-Seventeenth-Century Italy" * Mauro P. Calcagno: "Signifying Nothing: Debates on the Power of Voice in Seventeenth-Century Venice" * Georgia Cowart: "Le Bourgeois gentilhomme, the Ornaments of Fête and the Utopia of Theater" * Michael R. Dodds: "Modal Representation in Baroque Church-Tone Cycles" * Don Fader: "Sébastien de Brossard as Music Historian: a Modernist View of the Querelle des anciens et des modernes in Music" * Kimberlyn Montford: "Religious Reform, Legislation, and Nuns’ Music in Early Modern Rome" * Paologiovanni Maione: "Ò Giulia de Caro—from Whore to Impresario: On Cantarine and Theater in Naples in the Second Half of the Seventeenth Century" * Stephen R. Miller: "'Conflicting Signatures": Divergent Compositional Processes in Seventeenth-Century Imitative Textures" * Lois Rosow: "The Descending Tetrachord: An Emblem Expanded" * Sally Sanford and Paul Walker, w ith the ensemble Zephyrus: "Creating a Choral Sound for Music of the Prima and Seconda Pratica" * Catherine Gordon-Seifert: The Allemandes of Louis Couperin: Songs without Words" * Eleanor Selfridge-Field: The Rites of Autumn, Winter, and Spring: Decoding the Calendar of Venetian Opera" * Edmond Strainchamps: "The Sacred Music of Marco Da Gagliano" Conference Program, April 1999 (University of Virginia) FRIDAY MORNING NORTH ITALIAN MUSIC Margaret Murata, chair Gregory Barnett, "Chronicles of Musical Success and Failure in Late-Seventeenth-Century Italy" Apart from the music that we study, we know little of most seventeenth-century musicians.