Cusa Faith/Reason-Engl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cusanus, on Learned Igorance-17Z8dxd

On Learned Ignorance Harries 1 Karsten Harries Nicholas of Cusa On Learned Ignorance Seminar Notes Fall Semester 2015 Yale University Copyright Karsten Harries On Learned Ignorance Harries 2 Contents 1. Introduction 3 Book One 2. Learned Ignorance 17 3. The Coincidence of Opposites 30 4. The Threat of Pantheism 47 5. The Power of Mathematics 61 6. Naming God 76 Book Two 7. The Shape of the Universe 90 8. Matter and Becoming 105 9. The Condition of the Earth 118 Book Three 10. The Need for Christ 131 11. Death and Resurrection 146 12. Faith and Understanding 162 13. Death, Damnation, and the Church 176 On Learned Ignorance Harries 3 1. Introduction 1 Many philosophers today have become uneasy about what philosophy has become and where it has led us. Nietzsche and Heidegger, Derrida and Rorty are just a few names. Their uneasiness mirrors widespread concern about the shape of our modern culture. As more and more begin to suspect that the road on which we have been travelling may be a dead end, attempt are made to retrace steps taken; a search begins for missed turns and for those who may have misled us. Among these Descartes has long occupied a special place as the thinker whose understanding of proper method helped found modern philosophy, science, and indeed the shape of our technological world. It is thus to be expected that attempts to question modernity, to confront it, in order perhaps to take a step beyond it, should have often taken the form of attempts to confront Descartes or Cartesian rationality. -

Nicholas of Cusa and Islam

Nicholas of Cusa and Islam Ian Christopher Levy, Rita George-Tvrtković, and Donald F. Duclow - 9789004274761 Downloaded from Brill.com10/01/2021 12:32:35PM via free access Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions Edited by Andrew Colin Gow (Edmonton, Alberta) In cooperation with Sylvia Brown (Edmonton, Alberta) Falk Eisermann (Berlin) Berndt Hamm (Erlangen) Johannes Heil (Heidelberg) Susan C. Karant-Nunn (Tucson, Arizona) Martin Kaufhold (Augsburg) Erik Kwakkel (Leiden) Jürgen Miethke (Heidelberg) Christopher Ocker (San Anselmo and Berkeley, California) Founding Editor Heiko A. Oberman † VOLUME 183 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/smrt Ian Christopher Levy, Rita George-Tvrtković, and Donald F. Duclow - 9789004274761 Downloaded from Brill.com10/01/2021 12:32:35PM via free access Nicholas of Cusa and Islam Polemic and Dialogue in the Late Middle Ages Edited by Ian Christopher Levy Rita George-Tvrtković Donald F. Duclow LEIDEN | BOSTON Ian Christopher Levy, Rita George-Tvrtković, and Donald F. Duclow - 9789004274761 Downloaded from Brill.com10/01/2021 12:32:35PM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. -

Nicholas of Cusa and Modern Philosophy

//FS2/CUP/3-PAGINATION/HRP/2-PROOFS/3B2/9780521846486C09.3D 173 [173–192] 2.5.2007 8:03AM 9 DERMOT MORAN Nicholas of Cusa and modern philosophy ‘‘Gatekeeper of the modern age’’ Nicholas of Cusa (Niklas Krebs, known as Cusanus, 1401–64), one of the most original and creative intellects of the fifteenth century,1 has been variously described as ‘‘the last great philosopher of the dying Middle Ages’’ (Alexandre Koyre´), as a ‘‘transition-thinker’’ between the medieval and modern worlds (Frederick Copleston),2 and as the ‘‘gatekeeper of the modern age’’ (Rudolf Haubst).3 He is a lone figure with no real successor although he had some influence on Copernicus, Kepler, Bruno, and, tangen- tially, on Descartes. The German Idealists showed some interest in Nicholas of Cusa but the real revival of his thought was stimulated by the neo-Kantian philosopher Ernst Cassirer (1874–1945) who called him ‘‘the first modern thinker’’ and by the existentialist Karl Jaspers.4 Cassirer compared him to Kant for his view that objects have to be understood in terms of the categories of our own thought.5 Other scholars, notably Alexandre Koyre´,6 Hans-Georg Gadamer7 Hans Blumenberg,8 Werner Beierwaltes,9 and Karsten Harries,10 all see him in a certain way as a harbinger of modernity.11 Yet his outlook is essentially conservative, aiming, as Hans Blumenberg has recognized, to maintain the medieval synthesis.12 Cusanus was a humanist scholar, Church reformer – his De concordantia catholica (On Catholic Concord, 1434) included proposals for the reform of Church and state – papal diplomat, and Catholic cardinal. -

Separate Material Intellect in Averroes' Mature Philosophy Richard C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by epublications@Marquette Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Philosophy Faculty Research and Publications Philosophy, Department of 1-1-2004 Separate Material Intellect in Averroes' Mature Philosophy Richard C. Taylor Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. "Separate Material Intellect in Averroes' Mature Philosophy," in Words, Texts and Concepts Cruising the Mediterranean Sea. Eds. Gerhard Endress, Rud̈ iger Arnzen and J Thielmann. Leuven; Dudley, MA: Peeters, 2004: 289-309. Permalink. © 2004 Peeters Publishers. Used with permission. ORIENTALIA LOVANIENSIA ANALECTA ---139--- 'WORDS, TEXTS AND CONCEPTS CRUISING THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA Studies on the sources, contents and influences of Islamic civilization and Arabic philosophy and science Dedicated to Gerhard Endress on his sixty-fifth birthday edited by R. ARNZEN and J. THIELMANN UITGEVERIJ PEETERS en DEPARTEMENT OOSTERSE STUDIES LEUVEN - PARIS - DUDLEY, MA 2004 SEPARATE MATERIAL INTELLECT IN A VERROES' MATURE PHILOSOPHY Richard C. T AYLOR Marquette University, Milwaukee The doctrine of the material intellect promulgated by Averroes (i126- 1198) in his latest works is surely the teaching for which he has been most maligned both in the medieval era and in modern times. In medi eval times Duns Scotus spoke of "That accursed Averroes" whose "fan tastic conception, intelligible neither to himself nor to others, assumes the intellective part of man to be a sort -

Fsofime 22.Indb

COMPATIBILITY BETWEEN PHILOSOPHY AND MAGIC IN THE WORK OF ALBERTUS MAGNUS Compatibilidad entre Filosofía y Magia en la obra de Alberto Magno Rinotas Athanasios Kapodistrian University of Athens (Greece) ABSTRACT Albertus Magnus (1193?-1280), also known as doctor universalis, delved into several fields of science and philosophy, a pursuit which resulted in a massive production of works. Within these works, however, one discerns a provocative paradox, in which a cleric is involved in a forbidden art: magic. In this paper I argue that a paradox of this kind can be justified and explained in terms of philosophy. To this end, I advance three case studies to shed light on the afore-mentioned problem. First, I scrutinize indirect and direct sources in order to clarify Albertus’s relation to magic, thus addressing whether it is possible to trace any supportive data that permits a connection between magic and philosophy. Next, I show that this connection is achievable, since some parts of Albertus’s philosophy, such as psychology, cosmology and the liberum arbitrium, seem to be associated with magia naturalis in terms of astrology. Finally, I argue that the German philosopher was not successful in legitimizing magic through philosophy, and thus failed to prove himself a unique pioneer of an innovative body of knowledge. Keywords: Albertus Magnus, Magic, Astrology, Science, Philosophy. RESUMEN Alberto Magno (1193?-1280), también conocido como doctor universalis, profundizó en distintos campos de la ciencia y la filosofía, una búsqueda que dió como resultado una producción masiva de obra. No obstante, en este conjunto de obras uno puede descubrir una provocativa paradoja, en la que un clérigo se relaciona con un arte prohibido como la magia. -

Pál Bolberitz: the Beginnings of Hungarian Philosophy

A SZENT IS1V AN TIJDOMANYOS AKADEMIA SZEKFOGLALO ELOADASAI Uj Folyam. 2/2. szam Szerkeszti: STIRLING JANos OESSH fot.itkar PAL BOLBERITZ THE BEGINNINGS OF HUNGARIAN PHILOSOPHY (THE RECEPTION OF NICHOLAS OF CUSA IN THE WORK ,DE HOMINE" BY PETER CS6KAS LASKOI) BUDAPEST 2004 A SZENT IS1V AN TIJDOMANYOS AKADEMIA SZEKFOGLALO ELOADASAI Uj Folyam. 2/2. szam Szerkeszti: STIRLING JANos OESSH fot.itkar PAL BOLBERITZ THE BEGINNINGS OF HUNGARIAN PHILOSOPHY (THE RECEPTION OF NICHOLAS OF CUSA IN THE WORK ,DE HOMINE" BY PETER CS6KAS LASKOI) Magyarrryelven elhangzott a Matr~ar Tu:imdnyos A lwitfmia Felol1.J:lfJ3 tern11i1m 2003. novemher 25-in BUDAPEST 2004 Minden jog fenntartva, beleertve a btirminemu eljtirtissal val6 sokszorositds jogdt is © BOLBERITZ PAL 2004 KESZULT A SZENT ISTV ANTARSULAT, AZ APOSTOLI SZENTSZEK KONYVKIAOOJA NYOMDAJABAN. IGAZGATO: FARKAS OLIVER OESSH BUDAPEST, V. KOSSUTH LAJOS U. 1. PAL BOLBERITZ THE BEGINNINGS OF HUNGARIAN PHILOSOPHY (THE RECEPTION OF NICHOLAS OF CUSA IN THE WORK DE HOMINE BY PETER Cs6KAS LASK6I) The present study does not intend to get involved in the academic dispute flaring up from time to time to discuss whether there has ever been Hungarian philosophy or not. According to our view, Hungarian philosophy did, does and, hopefully, will exist, for it has its own proper ties. As it is well known, philosophy is the science inves tigating the ultimate principles and causes. It is not un common for the Hungarian spirit to examine the ultimate questions either. As expressed by the Latin phrases: pri mum vivere, -

Philosophy 305 a Early Medieval Philosophy (4Th to the 12Th Century CE)

1 Philosophy 305 A Early Medieval Philosophy (4th to the 12th Century CE) This course begins with a brief presentation of the philosophies of Plato, Aristotle and Plotinus insofar as these were influential on medieval philosophical thought. It then considers major thinkers in the Christian traditions from the 4th to the 12th century CE, and includes a brief introduction to major Islamic and Jewish philosophers within that time period insofar as their speculations were influential on medieval Christian philosophy. Instructor: E-H. W. Kluge Office: CLE B313 Phone: (250)721-7519 e-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Mondays and Thursdays 10:00am - 11:20am Text: Arthur Hyman, James J. Walsh, & Thomas Williams, eds. Philosophy in the Middle Ages (3rd ed.) Cambridge, MA: Hackett. Formal Course Requirements and Grading Procedures Grades will be based on two mid-terms and a final examination. The mid-term examinations are fifty minutes long and the final examination is three hours in length. The mid-term examinations are each worth 20% of the course grade; the final examination is worth 60%. Students who have taken (and received a grade for) both mid-term examinations have the option of having the final examination count for 100% of their course grade. The mid-term examinations cover only the material that has not been tested before in the semester; the final examination is cumulative and covers all of the material dealt with in the course. Students are encouraged to discuss their mid- term examination with the instructor. Significant dates: - Mid-term examination #1: app. October 1 - Mid-term examination #2: app. -

Catholic Theology in the Thirteenth Century and the Origins of Secularism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Mary Immaculate Research Repository and Digital Archive Article Catholic Theology in the Thirteenth Century and the Origins of Secularism Rik Van Nieuwenhove Mary Immaculate College, Limerick Abstract This article examines two distinct responses to the reception of Aristotle in the thirteenth century: the Bonaventurean and the Thomist. The outcome of this debate (and the Condemnations of 1277) led to the modern separation of faith and reason. Rather than seeing voluntarism and nominalism as the cause of the modern separation of faith and reason, and theology and philosophy, it will be suggested that it is actually the other way around: the Bonaventurean response indirectly resulted in the growing separation of faith and reason, which led, in turn, to voluntarism. It is important not to confuse the Thomist and Franciscan responses, as sometimes happens in recent scholarship, including in the work of Gavin D’Costa, as will be shown. Both the Thomist and the Bonaventurean approaches are legitimate resources to respond to the (post)-secular context in which we find ourselves, and the former should not be reduced to the latter. Keywords Aquinas and Bonaventure, faith and reason, origins of modernity n this article I want to revisit debates that took place at the end of the thirteenth cen- Itury. From a historical point of view it is exactly in this period that we find the origins of secularism and modernity, especially the growing separation of faith -

NICHOLAS of CUSA's DEBATE with JOHN WENCK a Translation and an Appraisal of De Ignota Litteratura and Apologia Doctae Ignorantiae

NICHOLAS OF CUSA'S DEBATE WITH JOHN WENCK A Translation and an Appraisal of De Ignota Litteratura and Apologia Doctae Ignorantiae by JASPER HOPKINS THE ARTHUR J. BANNING PRESS MINNEAPOLIS The English translation of Apologia Doctae Ignorantiae is made from Nicolai de Cusa Opera Omnia, Vol. II, edited by Raymond Klibansky (Leipzig: F. Meiner, 1932). Third edition, 1988 (First edition, 1981) Copyright © 1981 by The Arthur J. Banning Press, Minneapolis, Min- nesota 55402. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 80-82908 ISBN 0-938060-40-6 458 1 A DEFENSE OF LEARNED IGNORANCE FROM ONE DISCIPLE TO ANOTHER (Apologia Doctae Ignorantiae Discipuli ad Discipulum) by NICHOLAS OF CUSA Our common teacher, master Nicholas of Cusa, now added to the Col- lege of Cardinals, once told me how well you understand the coinci- dences which he disclosed to us in the books of Learned Ignorance (presented to the Apostolic Legate)1 and in many of his other works. [He spoke of] your ardent wish to gather together everything which here and there flows from him regarding these matters. [He also re- ported] that you do not allow any of the learned men to pass by you without talking with them about this approach. [And he mentioned] that you have induced many who had despised this study to break for a short while with their long-standing habit of laboring with the Aris- totelian tradition and to give themselves over to these considerations, in the faith that something important lies hidden therein—[to give themselves] to the extent that with an inward relish they become more deeply attracted and come to realize that this approach differs from others as much as sight differs from hearing. -

The Concept of Non-Duality in Śaṅkara and Cusanus

Comparative Philosophy Volume 12, No. 1 (2021): 98-110 Open Access / ISSN 2151-6014 / www.comparativephilosophy.org https://doi.org/10.31979/2151-6014(2021).120109 THE CONCEPT OF NON-DUALITY IN ŚAṄKARA AND CUSANUS JEROME KLOTZ ABSTRACT: When comparing diverse philosophical traditions, it becomes necessary to establish a common point of departure. This paper offers a comparative analysis of Advaita Vedānta Hinduism and esoteric Christianity, as represented by the two highly celebrated figures of Śaṅkara and Nicholas Cusanus, respectively. The common point of departure on which I base this comparison is the concept of “non-duality”—a concept that is fitting for at least two reasons. First, it is general enough to encompass both traditions, pervading the work of each figure, and thus allowing for a kind of “shared language.” Second, it is specific enough to identify a set of core and well-defined principles amenable to systematic study, chief among which are the notions of (1) the “Absolute” as an infinite unity that transcends all determinations (“no-thing”) and exceeds all oppositions (“not-other”), and (2) the world as an ontologically ambiguous “reflection” that simultaneously hides and manifests its meta- ontological Principle. In drawing these connections, I hope to show how the concept of non- duality provides the possibility for a mutual understanding among diverse traditions at the philosophical level. Keywords: Advaita Vedānta, metaphysics, mysticism, Nicholas Cusanus, non-duality, Śaṅkara 1. INTRODUCTION The concept of “non-duality” is not the exclusive possession of any one philosophical system. On the contrary, it can be found—mutatis mutandis—within religio- philosophical traditions the world over: from Philosophical Daoism, Mahāyāna Buddhism, and Advaita Vedānta Hinduism in the East, to Kabbalistic Judaism, esoteric Christianity, and mystical Islam in the West. -

A-Z Entries List

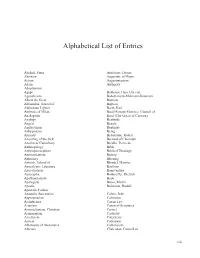

Alphabetical List of Entries Abelard, Peter Attributes, Divine Abortion Augustine of Hippo Action Augustinianism Adam Authority Adoptionism Agape Balthasar, Hans Urs von Agnosticism Bañezianism-Molinism-Baianism Albert the Great Baptism Alexandria, School of Baptists Alphonsus Liguori Barth, Karl Ambrose of Milan Basel-Ferrara-Florence, Council of Anabaptists Basil (The Great) of Caesarea Analogy Beatitude Angels Beauty Anglicanism Beguines Anhypostasy Being Animals Bellarmine, Robert Anointing of the Sick Bernard of Clairvaux Anselm of Canterbury Bérulle, Pierre de Anthropology Bible Anthropomorphism Biblical Theology Antinomianism Bishop Antinomy Blessing Antioch, School of Blondel, Maurice Apocalyptic Literature Boethius Apocatastasis Bonaventure Apocrypha Bonhoeffer, Dietrich Apollinarianism Book Apologists Bucer, Martin Apostle Bultmann, Rudolf Apostolic Fathers Apostolic Succession Calvin, John Appropriation Calvinism Architecture Canon Law Arianism Canon of Scriptures Aristotelianism, Christian Carmel Arminianism Casuistry Asceticism Catechesis Aseitas Catharism Athanasius of Alexandria Catholicism Atheism Chalcedon, Council of xiii Alphabetical List of Entries Character Diphysitism Charisma Docetism Chartres, School of Doctor of the Church Childhood, Spiritual Dogma Choice Dogmatic Theology Christ/Christology Donatism Christ’s Consciousness Duns Scotus, John Chrysostom, John Church Ecclesiastical Discipline Church and State Ecclesiology Circumincession Ecology City Ecumenism Cleric Edwards, Jonathan Collegiality Enlightenment -

Download Download

Prophetic Parables and Philosophic Falsehoods Samuel Scolnicov In memoriam The writings of Arisotle’s teacher Plato are in parables and hard to understand. One can dispense with them, for the writings of Arisotle suffice and we need not occupy [our attention] with writings of earlier [philosophers]. * So writes Maimonides to Ibn Tibbon, the translator of the Guide o f the Per plexed into Hebrew. Aristotle’s works, he says, are ‘the roots and foundations of all work on the sciences’ and all that preceded him were (as indeed Aristotle himself saw them) conducive to him and superseded by him. Indeed, Plato was read — even when directly and not mediated by commentaries and epitomes — through Aristotle. Alfarabi, conspicuously, writes his Agreement of Plato and Aristotle. But even those who recognized the difference between them still un derstood Plato in essential respects as an Aristotelian. This is nowhere as evident — and as distorting — as in the Aristotelization of Plato’s epistemology. But more on this presently. On the other hand, it is commonplace that Platonic political philosophy, with its clear normative orientation, was much more congenial to religious thought than Aristotle’s rather more descriptive and analytical approach. The prophet, Moses or Muhammad,2 is he who establishes the political order divinely sanc tioned and henceforth entrusted to the religious establishment. And so it is that here, by contrast, Aristotle is unwittingly assimilated to Plato, to the extent that Averroes in his Commentary on the Republic can confidently present Plato’s political philosophy as doing duty for Aristotle’s, which he did not know first hand.3 In Christianity, this Platonization of political thought is made more difficult by Jesus’ dissociation of religion from political power: ‘Render unto Caesar the Letter of Maimonides to Samuel Ibn Tibbon.