S. 691 [Report No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposed Finding

This page is intentionally left blank. Pamunkey Indian Tribe (Petitioner #323) Proposed Finding Proposed Finding The Pamunkey Indian Tribe (Petitioner #323) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................... ii INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................1 Regulatory Procedures .............................................................................................1 Administrative History.............................................................................................2 The Historical Indian Tribe ......................................................................................4 CONCLUSIONS UNDER THE CRITERIA (25 CFR 83.7) ..............................................9 Criterion 83.7(a) .....................................................................................................11 Criterion 83.7(b) ....................................................................................................21 Criterion 83.7(c) .....................................................................................................57 Criterion 83.7(d) ...................................................................................................81 Criterion 83.7(e) ....................................................................................................87 Criterion 83.7(f) ...................................................................................................107 -

Ocanahowan and Recently Discovered Linguistic

2 OCANAHOWAN AND RECENTLY DISCOVERED LINGUISTIC FRAGMENTS FROM SOUTHERN VIRGINIA, C. 1650 Philip Barbour Ridgefield, Connecticut Published in: Papers of the 7th Algonquian Conference (1975) Ocanahowan (or Ocanahonan and other spellings) was the name of an Indian town or village, region or tribe, which was first reported in Captain John Smith's True Relation in 1608 and vanished from the records after Smith mentioned it for the last time 1624, until it turned up again in a few handwritten lines in the back of a book. Briefly, these lines cover half a page of a small quarto, and have been ascribed to the period from about 1650 to perhaps the end of the century, on the basis of style of writing. The page in question is the blank verso of the last page in a copy of Robert Johnson's Nova Britannia, published in London in 1604, now in the possession of a distinguished bibliophile of Williamsburg, Virginia. When I first heard about it, I was in London doing research and brushing up on the English language, Easter-time 1974, and Bernard Quaritch, Ltd., got in touch with me about "some rather meaningless annotations" in a small volume they had for sale. Very briefly put, for I shall return to the matter in a few minutes, I saw that the notes were of the time of the Jamestown colony and that they contained a few Powhatan words. Now that the volume has a new owner, and I have his permission to xerox and talk about it, I can explain why it aroused my interest to such an extent. -

EPA Interim Evaluation of Virginia's 2016-2017 Milestones

Interim Evaluation of Virginia’s 2016-2017 Milestones Progress June 30, 2017 EPA INTERIM EVALUATION OF VIRGINIA’s 2016-2017 MILESTONES As part of its role in the accountability framework, described in the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (Bay TMDL) for nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is providing this interim evaluation of Virginia’s progress toward meeting its statewide and sector-specific two-year milestones for the 2016-2017 milestone period. In 2018, EPA will evaluate whether each Bay jurisdiction achieved the Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) partnership goal of practices in place by 2017 that would achieve 60 percent of the nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment reductions necessary to achieve applicable water quality standards in the Bay compared to 2009. Load Reduction Review When evaluating 2016-2017 milestone implementation, EPA is comparing progress to expected pollutant reduction targets to assess whether statewide and sector load reductions are on track to have practices in place by 2017 that will achieve 60 percent of necessary reductions compared to 2009. This is important to understand sector progress as jurisdictions develop the Phase III Watershed Implementation Plans (WIP). Loads in this evaluation are simulated using version 5.3.2 of the CBP partnership Watershed Model and wastewater discharge data reported by the Bay jurisdictions. According to the data provided by Virginia for the 2016 progress run, Virginia is on track to achieve its statewide 2017 targets for nitrogen and phosphorus but is off track to meet its statewide targets for sediment. The data also show that, at the sector scale, Virginia is off track to meet its 2017 targets for nitrogen reductions in the Agriculture, Urban/Suburban Stormwater and Septic sectors and is also off track for phosphorus in the Urban/Suburban Stormwater sector, and off track for sediment in the Agriculture and Urban/Suburban Stormwater sectors. -

Native Americans in Our Area

Early Native Americans In Our Area Written & Published by the Waynesboro Historical Commission Founded 1971 Waynesboro, Virginia 22980 Dedication The Historic Commission of Waynesboro dedicates this publication to the earliest settlers of the North American Continent and in particular Virginia and our immediate region. Their relentless push through an unmarked environment exemplifies the quest of the human spirit to reach the horizon and make it its own. Until relatively recently, a history of America would devote a slight section to the Indian tribes discovered by the colonists who landed on the North American continent. The subsequent text would detail the claiming of the land, the creation of towns and villages, and the conquering of the forces that would halt the relentless move to the West. That view of history has been challenged by the work of archeologists who have used the advances in science and the skills of excavation to reveal a past that had been forgotten or deliberatively ignored. This publication seeks to present a concise chronicle of the prehistory of our country and our region with attention to one of the forgotten and marginalized civilizations, the Monacans who existed and prospered in Central Virginia and the areas immediate to Waynesboro. Migration to North America Well before the Romans, the Greeks, or the Egyptians created the culture we call Western Civilization, an ethnic group known as the “First People” began its colonization of the North American continent. There are a number of theories of how the original settlers came to the continent. Some thought they were the “Lost Tribes” of the Old Testament. -

The Devil in Virginia: Fear in Colonial Jamestown, 1607-1622

The Devil in Virginia: Fear in Colonial Jamestown, 1607-1622 Matthew John Sparacio Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History Crandall A. Shifflett, Chair A. Roger Ekirch Brett L. Shadle 16 March 2010 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Early Modern England; Colonial Virginia; Jamestown; Devil; Fear Copyright 2010, Matthew John Sparacio The Devil in Virginia: Fear in Colonial Jamestown, 1607-1622 Matthew John Sparacio ABSTRACT This study examines the role of emotions – specifically fear – in the development and early stages of settlement at Jamestown. More so than any other factor, the Protestant belief system transplanted by the first settlers to Virginia helps explain the hardships the English encountered in the New World, as well as influencing English perceptions of self and other. Out of this transplanted Protestantism emerged a discourse of fear that revolved around the agency of the Devil in the temporal world. Reformed beliefs of the Devil identified domestic English Catholics and English imperial rivals from Iberia as agents of the diabolical. These fears travelled to Virginia, where the English quickly ʻsatanizedʼ another group, the Virginia Algonquians, based upon misperceptions of native religious and cultural practices. I argue that English belief in the diabolic nature of the Native Americans played a significant role during the “starving time” winter of 1609-1610. In addition to the acknowledged agency of the Devil, Reformed belief recognized the existence of providential actions based upon continued adherence to the Englishʼs nationally perceived covenant with the Almighty. -

Defining the Greater York River Indigenous Cultural Landscape

Defining the Greater York River Indigenous Cultural Landscape Prepared by: Scott M. Strickland Julia A. King Martha McCartney with contributions from: The Pamunkey Indian Tribe The Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe The Mattaponi Indian Tribe Prepared for: The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay & Colonial National Historical Park The Chesapeake Conservancy Annapolis, Maryland The Pamunkey Indian Tribe Pamunkey Reservation, King William, Virginia The Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe Adamstown, King William, Virginia The Mattaponi Indian Tribe Mattaponi Reservation, King William, Virginia St. Mary’s College of Maryland St. Mary’s City, Maryland October 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As part of its management of the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail, the National Park Service (NPS) commissioned this project in an effort to identify and represent the York River Indigenous Cultural Landscape. The work was undertaken by St. Mary’s College of Maryland in close coordination with NPS. The Indigenous Cultural Landscape (ICL) concept represents “the context of the American Indian peoples in the Chesapeake Bay and their interaction with the landscape.” Identifying ICLs is important for raising public awareness about the many tribal communities that have lived in the Chesapeake Bay region for thousands of years and continue to live in their ancestral homeland. ICLs are important for land conservation, public access to, and preservation of the Chesapeake Bay. The three tribes, including the state- and Federally-recognized Pamunkey and Upper Mattaponi tribes and the state-recognized Mattaponi tribe, who are today centered in their ancestral homeland in the Pamunkey and Mattaponi river watersheds, were engaged as part of this project. The Pamunkey and Upper Mattaponi tribes participated in meetings and driving tours. -

Remembering the River: Traditional Fishery Practices, Environmental Change and Sovereignty on the Pamunkey Indian Reservation

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2019 Remembering the River: Traditional Fishery Practices, Environmental Change and Sovereignty on the Pamunkey Indian Reservation Alexis Jenkins Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons Recommended Citation Jenkins, Alexis, "Remembering the River: Traditional Fishery Practices, Environmental Change and Sovereignty on the Pamunkey Indian Reservation" (2019). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1423. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1423 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Pamunkey Chief and Tribal Council for their support of this project, as well as the Pamunkey community members who shared their knowledge and perspectives with this researcher. I am incredibly honored to have worked under the guidance of Dr. Danielle Moretti-Langholtz, who has been a dedicated and inspiring mentor from the beginning. I also thank Dr. Ashley Atkins Spivey for her assistance as Pamunkey Tribal Liaison and for her review of my thesis as a member of the committee and am further thankful for the comments of committee members Dr. Martin Gallivan and Dr. Andrew Fisher, who provided valuable insight during the process. I would like to express my appreciation to the VIMS scientists who allowed me to volunteer with their lab and to the The Roy R. -

Indian Peoples, Nations and Violence in the Seventeenth-Century Chesapeake

CERTAINE BOUNDES: INDIAN PEOPLES, NATIONS AND VIOLENCE IN THE SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY CHESAPEAKE By JESSICA TAYLOR A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2017 © 2017 Jessica Taylor To Mimi, you are worth so much ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my advisor, Juliana Barr, for her thoughtful and sincere support. I am so glad to have her in my life. My committee members Marty Hylton, Jon Sensbach, Elizabeth Dale, and Paul Ortiz each offered different paths to new thoughts and perspectives. My co-workers, students, and friends at the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program helped me gain the confidence to pursue new ideas and goals. I thank all of the wonderful people who have read drafts of chapters and talked ideas through with me including Jeffrey Flanagan, Matt Saionz, Johanna Mellis, Rebecca Lowe, David Shope, Roberta Taylor, Robert Taber, David Brown, Elyssa Hamm. Thank you to Eleanor Deumens for editing my footnotes and offering wonderful suggestions. I thank the Virginia Historical Society, the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, and the Mary and David Harrison Institute for American History, Literature, and Culture for their financial support of my research for this project. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................... -

Marion F. Werkheiser, Attorney for the Monacan Indian Nation, (703) 489-6059, [email protected]

THE MONACAN INDIAN NATION URGES YOU TO HELP SAVE RASSAWEK The James River Water Authority (JRWA) plans to build a water pump station on top of Rassawek, the Monacans’ capital city documented by John Smith in his 1612 Map of Virginia (see image). JRWA must move the project to an alternative location so that Rassawek can be saved for future generations and Monacan ancestors can be allowed to rest in peace. • Rassawek was located at the confluence of the Rivanna and James Rivers, and John Smith described it as the capital city to which all other Monacan towns paid tribute. Researchers from the Smithsonian verified the location in the 1880s and again in the 1930s, and the Commonwealth of Virginia has included the Rassawek archaeological site in its files since at least 1980. It is the Monacan equivalent of Werowocomoco, the Powhatan capital now planned to be a national park. • JRWA (a joint venture of Louisa and Fluvanna Counties) proposes to build a pump station to deliver water to help attract economic development, such as prospective breweries and data centers, in Zion Crossroads. JRWA chose the Rassawek site because they thought it would be the least expensive of several options. Building the pump station on top of Rassawek will mean that the site will be obliterated and Monacan burials will likely be disturbed. • Monacan tribal members have participated in several previous repatriation ceremonies previously, and these are somber and traumatizing occasions that the tribe does not enter into lightly or when other options exist. The Monacan Indian Nation has asked the Department of Historic Resources to deny JRWA’s burial permit application and not allow them to dig up Monacan ancestors. -

Living with the Indians Introduction

LIVING WITH THE INDIANS Introduction Archaeologists believe the American Indians were the first people to arrive in North America, perhaps having migrated from Asia more than 16,000 years ago. During this Paleo time period, these Indians rapidly spread throughout America and were the first people to live in Virginia. During the Woodland period, which began around 1200 B.C., Indian culture reached its high- est level of complexity. By the late 16th century, Indian people in Coastal Plain Virginia, united under the leadership of Wahunsonacock, had organized themselves into approximately 32 tribes. Wahunsonacock was the paramount or supreme chief, having held the title “Powhatan.” Not a personal name, the Powhatan title was used by English settlers to identify both the leader of the tribes and the people of the paramount chiefdom he ruled. Although the Powhatan people lived in separate towns and tribes, each led by its own chief, their language, social structure, religious beliefs and cultural traditions were shared. By the time the first English settlers set foot in “Tsena- commacah, or “densely inhabited land,” the Powhatan Indians had developed a complex culture with a centralized political system. Living With the Indians is a story of the Powhatan people who lived in early 17th-century Virginia— their social, political, economic structures and everyday life ways. It is the story of individuals, cultural interactions, events and consequences that frequently challenged the survival of the Pow- hatan people. It is the story of how a unique culture, through strong kinship networks and tradition, has endured and maintained tribal identities in Virginia right up to the present day. -

Red Albion: Genocide and English Colonialism, 1622-1646

RED ALBION: GENOCIDE AND ENGLISH COLONIALISM, 1622-1646 by MATTHEW KRUER A THESIS Presented to the Department ofHistory and the Graduate School ofthe University of Oregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofArts June 2009 11 "Red Albion: Genocide and English Colonialism, 1622-1646," a thesis prepared by Matthew Kruer in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master ofArts degree in the Department ofHistory. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: Dr. Jiitk M~dd~~, Chai~~i1the Examining Committee Date . Committee in Charge: Dr. Jack Maddex, Chair Dr. Matthew Dennis Dr. Jeffrey Ostler Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School III © 2009 Matthew Ryan Kruer IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Matthew Kruer for the degree of Master ofArts in the Department of History to be taken June 2009 Title: RED ALBION: GENOCIDE AND ENGLISH COLONIALISM, 1622-1646 Approved: Dr. Jack Maddex This thesis examines the connection between colonialism and violence during the early years ofEnglish settlement in North America. I argue that colonization was inherently destructive because the English colonists envisioned a comprehensive transformation ofthe American landscape that required the elimination ofNative American societies. Two case studies demonstrate the dynamics ofthis process. During the Anglo-Powhatan Wars in Virginia, latent violence within English ideologies ofimperialism escalated cont1ict to levels ofextreme brutality, but the fracturing ofpower along the frontier limited Virginian war aims to expulsion ofthe Powhatan Indians and the creation ofa segregated society. During the Pequot War in New England, elements ofviolence in the Puritan worldview became exaggerated by the onset ofsocietal crisis during the Antinomian Controversy. -

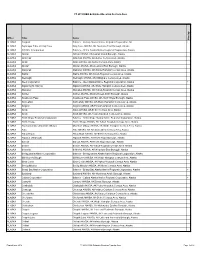

FY 2019 IHBG Estimate Allocation Formula Area

FY 2019 IHBG Estimate Allocation Formula Area Office Tribe Name Overlap ALASKA Afognak Balance - Koniag Alaska Native Regional Corporation, AK + ALASKA Agdaagux Tribe of King Cove King Cove ANVSA, AK-Aleutians East Borough, Alaska ALASKA AHTNA, Incorporated Balance - Ahtna Alaska Native Regional Corporation, Alaska ALASKA Akhiok Akhiok ANVSA, AK-Kodiak Island Borough, Alaska ALASKA Akiachak Akiachak ANVSA, AK-Bethel Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Akiak Akiak ANVSA, AK-Bethel Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Akutan Akutan ANVSA, AK-Aleutians East Borough, Alaska ALASKA Alakanuk Alakanuk ANVSA, AK-Wade Hampton Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Alatna Alatna ANVSA, AK-Yukon-Koyukuk Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Aleknagik Aleknagik ANVSA, AK-Dillingham Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Aleut Corporation Balance - Aleut Alaska Native Regional Corporation, Alaska + ALASKA Algaaciq (St. Mary's) Algaaciq ANVSA, AK-Wade Hampton Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Allakaket Allakaket ANVSA, AK-Yukon-Koyukuk Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Ambler Ambler ANVSA, AK-Northwest Arctic Borough, Alaska ALASKA Anaktuvuk Pass Anaktuvuk Pass ANVSA, AK-North Slope Borough, Alaska ALASKA Andreafski Andreafsky ANVSA, AK-Wade Hampton Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Angoon Angoon ANVSA, AK-Hoonah-Angoon Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Aniak Aniak ANVSA, AK-Bethel Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Anvik Anvik ANVSA, AK-Yukon-Koyukuk Census Area, Alaska ALASKA Arctic Slope Regional Corporation Balance - Arctic Slope Alaska Native Regional Corporation, Alaska ALASKA Arctic Village Arctic Village ANVSA, AK-Yukon-Koyukuk