DATS Spring Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rhetoric of the Saints in Middle English Bibiical Drama by Chester N. Scoville a Thesis Submitted in Conformity with The

The Rhetoric of the Saints in Middle English BibIical Drama by Chester N. Scoville A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English University of Toronto O Copyright by Chester N. Scoville (2000) National Library Bibiiotheque nationale l*l ,,na& du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rwW~gtm OttawaON KlAûîU4 OtÈewaûN K1AW canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otheMrise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract of Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2000 Department of English, University of Toronto The Rhetoric of the Saints in Middle English Biblical Dnma by Chester N. Scovilie Much past criticism of character in Middle English drarna has fallen into one of two rougtily defined positions: either that early drama was to be valued as an example of burgeoning realism as dernonstrated by its villains and rascals, or that it was didactic and stylized, meant primarily to teach doctrine to the faithfùl. -

Tartan As a Popular Commodity, C.1770-1830. Scottish Historical Review, 95(2), Pp

Tuckett, S. (2016) Reassessing the romance: tartan as a popular commodity, c.1770-1830. Scottish Historical Review, 95(2), pp. 182-202. (doi:10.3366/shr.2016.0295) This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/112412/ Deposited on: 22 September 2016 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk SALLY TUCKETT Reassessing the Romance: Tartan as a Popular Commodity, c.1770-1830 ABSTRACT Through examining the surviving records of tartan manufacturers, William Wilson & Son of Bannockburn, this article looks at the production and use of tartan in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. While it does not deny the importance of the various meanings and interpretations attached to tartan since the mid-eighteenth century, this article contends that more practical reasons for tartan’s popularity—primarily its functional and aesthetic qualities—merit greater attention. Along with evidence from contemporary newspapers and fashion manuals, this article focuses on evidence from the production and popular consumption of tartan at the turn of the nineteenth century, including its incorporation into fashionable dress and its use beyond the social elite. This article seeks to demonstrate the contemporary understanding of tartan as an attractive and useful commodity. Since the mid-eighteenth century tartan has been subjected to many varied and often confusing interpretations: it has been used as a symbol of loyalty and rebellion, as representing a fading Highland culture and heritage, as a visual reminder of the might of the British Empire, as a marker of social status, and even as a means of highlighting racial difference. -

Dictionary of Norfolk Furniture Makers 1 700-1 840

THE DICTIONARY NORFOLK FURNITURE MAKERS 1700-1840 ABEL, Anthony, cm, 5 Upper Westwick Street, Free [?by purchase] 21/9/1664. Norwich (1778-1802). P 1734 (sen.). 1/12/1778 Apprenticed to Jonathan Hales, King’s ALLOYCE, Abraham jun., tur, St Lawrence, Lynn, £50 (5 yrs). Norwich (1695-1735). D1802. Free 4/3/1695 as s.o. Abraham Alloyce. ABEL, Daniel, up, Pottergate Street; then Bedford P 1710, 1714. 1734 (jun.). 1734/5 - supplement Street, Norwich (1838-1868). (Aloyce). These entries may be for A.A. sen. apart Apprenticed to Thomas Bennett. Free 25/7/1838. from 1734 where both are entered. D 1852, 1854 - cm up, Pottergate St. 1864, 1868 ALLURED, John, up, Market Place, Yarmouth - Bedford St., St Andrews. (1783-1797). ABEL, Thomas, cm, Pitt Street, Norwich App to William Seaman 19/3/1783* (James (1839-1842). D 1839, 1842. Allured), free 15/6/1790. ADCOCK, John, joi, St. Andrew, Norwich Took app William Lyall, 25/12/1790, £40 (5 yrs); (1715-1735). George Allured, 15/12/1792, £20. 28/4/1715 Apprenticed to Charles King, £4. Free NC 5/8/1797: ...John Allured, the younger, of 15/8/1722 as son of Thomas Adcock, tailor. Great Yarmouth...Upholsterer...declared a P 1734, 1734/5 supplement. Bankrupt. ALDEN, James, cm, Norwich (1814). NC 23/9/1797: Auction...Sept. 26, 1797...[4 NM 3/12/1814: Sunday last was married, at St. d ays]...All the genuine Stock in Trade and Giles’s, Mr. James Alden, cabinet-maker, to Miss Household Furniture of Mr. John Allured, Steavens, both of this city. -

Historic Furnishings Assessment, Morristown National Historical Park, Morristown, New Jersey

~~e, ~ t..toS2.t.?B (Y\D\L • [)qf- 331 I J3d-~(l.S National Park Service -- ~~· U.S. Department of the Interior Historic Furnishings Assessment Morristown National Historical Park, Morristown, New Jersey Decemb r 2 ATTENTION: Portions of this scanned document are illegible due to the poor quality of the source document. HISTORIC FURNISHINGS ASSESSMENT Ford Mansion and Wic·k House Morristown National Historical Park Morristown, New Jersey by Laurel A. Racine Senior Curator ..J Northeast Museum Services Center National Park Service December 2003 Introduction Morristown National Historical Park has two furnished historic houses: The Ford Mansion, otherwise known as Washington's Headquarters, at the edge of Morristown proper, and the Wick House in Jockey Hollow about six miles south. The following report is a Historic Furnishings Assessment based on a one-week site visit (November 2001) to Morristown National Historical Park (MORR) and a review of the available resources including National Park Service (NPS) reports, manuscript collections, photographs, relevant secondary sources, and other paper-based materials. The goal of the assessment is to identify avenues for making the Ford Mansion and Wick House more accurate and compelling installations in order to increase the public's understanding of the historic events that took place there. The assessment begins with overall issues at the park including staffing, interpretation, and a potential new exhibition on historic preservation at the Museum. The assessment then addresses the houses individually. For each house the researcher briefly outlines the history of the site, discusses previous research and planning efforts, analyzes the history of room use and furnishings, describes current use and conditions, indicates extant research materials, outlines treatment options, lists the sources consulted, and recommends sourc.es for future consultation. -

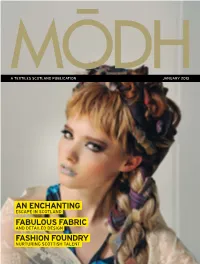

Modh-Textiles-Scotland-Issue-4.Pdf

A TEXTILES SCOTLAND PUBLICATION JANUARY 2013 AN ENCHANTING ESCAPE IN SCOTLAND FABULOUS FABRIC AND DETAILED DESIGN FASHION FOUNDRY NURTURING SCOTTISH TALENT contents Editor’s Note Setting the Scene 3 Welcome from Stewart Roxburgh 21 Make a statement in any room with inspired wallpaper Ten Must-Haves for this Season An Enchanting Escape 4 Some of the cutest products on offer this season 23 A fashionable stay in Scotland Fabulous Fabric Fashion Foundry 6 Uncovering the wealth of quality fabric in Scotland 32 Inspirational hub for a new generation Fashion with Passion Devil is in the Detail 12 Guest contributor Eric Musgrave shares his 38 Dedicated craftsmanship from start to fi nish thoughts on Scottish textiles Our World of Interiors Find us 18 Guest contributor Ronda Carman on why Scotland 44 Why not get in touch – you know you want to! has the interiors market fi rmly sewn up FRONT COVER Helena wears: Jacquard Woven Plaid with Herringbone 100% Merino Wool Fabric in Hair by Calzeat; Poppy Soft Cupsilk Bra by Iona Crawford and contributors Lucynda Lace in Ivory by MYB Textiles. Thanks to: Our fi rst ever guest contributors – Eric Musgrave and Ronda Carman. Read Eric’s thoughts on the Scottish textiles industry on page 12 and Ronda’s insights on Scottish interiors on page 18. And our main photoshoot team – photographer Anna Isola Crolla and assistant Solen; creative director/stylist Chris Hunt and assistant Emma Jackson; hair-stylist Gary Lees using tecni.art by L’Oreal Professionnel and the ‘O’ and irons by Cloud Nine, and make-up artist Ana Cruzalegui using WE ARE FAUX and Nars products. -

9111-Baildon-Mills-Brochure.Pdf

A PRESTIGIOUS DEVELOPMENT OF 1, 2, 3 & 4 BEDROOM HOMES CONTENTS 4 WELCOME TO BAILDON MILLS 6 THE HISTORY OF THE MILL 7 EXPERIENCE EXECUTIVE COUNTRY LIVING 8 INTRODUCING BAILDON 10 THE MOORS ON YOUR DOORSTEP 12 SURROUNDING CITIES HERITAGE LOOKS. 14 LOCATION & TRANSPORT 16 DEVELOPMENT OVERVIEW MODERN LIVING. 18 A SUPERIOR SPECIFICATION 21 SITE PLAN Steeped in history and brimming with character, your new home 22 PENNYTHORN at Baildon Mills will offer both traditional charm whilst being thoughtfully designed for modern living. Considered by many as one of 24 LONG RIDGE Yorkshire’s best places to live, a 26 HAWKSWORTH new home at Baildon Mills means 28 HIGH MOOR you’ll enjoy a lifestyle like no other. 29 REVA HILL 34 KMRE’S INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY 2 3 WELCOME to BAILDON MILLS Carefully considered design means that these homes will his truly unique project will convert a beautiful, historic textile mill into a thriving community of executive new homes, in the heart of Baildon village. maintain many of the stunning T heritage features that made the Carefully considered design means that these Whether you are looking for a light and airy, open- old textile mill such a popular homes will maintain many of the stunning heritage plan dining kitchen or something a little more piece of local architecture features that made the old textile mill such a traditional, our architects have considered all the popular piece of local architecture. Allowing you ways modern living can influence how we like to to enjoy the ease and convenience of buying new, configure our homes. -

Digitizing Traditional Lao Textile to Modern Weave Technique

Chinese Business Review, Nov. 2016, Vol. 15, No. 11, 547-555 doi: 10.17265/1537-1506/2016.11.004 D DAVID PUBLISHING Digitizing Traditional Lao Textile to Modern Weave Technique Lathsamy Chidtavong National University of Laos (NUOL), Vientiane Capital, Laos Michael Winckler, Hans Georg Bock Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany Marion Ellwanger-Mohr University of Applied Sciences, Mönchengladbach, Germany Traditional Lao textiles are wealth in religious motifs, the motifs and patterns on the textiles reflect traditions, beliefs and livelihood of people. The structure of Lao motifs and patterns are complicated, but weaving processes still use traditional techniques and simple floor-loom. Therefore, it takes a lot of time for making a weave-draft on the loom and percentage of losing weave-drafts is very high. In contrast, industrial textiles use electronic loom and digital weave-drafts to produce fabrics, which are suitable for fast production but lack complicated traditional patterns. As a result, this paper introduces scientific approaches for digitizing motifs, patterns, and weave-drafts of traditional Lao textiles. Mathematical principles of Frieze and Wallpaper groups are investigated for digital design. The paper presents two standard files, image file format and WIF file as digital weave-draft in order to fill the gap between traditional and modern weave techniques. The standard files are understandable and usable for both hand-weavers and weaving machines. Our study shows that a modern electronic TC2 loom is a suitable loom to connect between traditional Lao weave technique and modern weave technique. Keywords: frieze group, wallpaper group, Lao textile, WIF file and TC2 loom Introduction Laos consists of a variety of ethnic groups that are rich in traditions and cultures. -

Weaving Twill Damask Fabric Using ‘Section- Scale- Stitch’ Harnessing

Indian Journal of Fibre & Textile Research Vol. 40, December 2015, pp. 356-362 Weaving twill damask fabric using ‘section- scale- stitch’ harnessing R G Panneerselvam 1, a, L Rathakrishnan2 & H L Vijayakumar3 1Department of Weaving, Indian Institute of Handloom Technology, Chowkaghat, Varanasi 221 002, India 2Rural Industries and Management, Gandhigram Rural Institute, Gandhigram 624 302, India 3Army Institute of Fashion and Design, Bangalore 560 016, India Received 6 June 2014; revised received and accepted 30 July 2014 The possibility of weaving figured twill damask using the combination of ‘sectional-scaled- stitched’ (SSS) harnessing systems has been explored. Setting of sectional, pressure harness systems used in jacquard have been studied. The arrangements of weave marks of twill damask using the warp face and weft face twills of 4 threads have been analyzed. The different characteristics of the weave have been identified. The methodology of setting the jacquard harness along with healds has been derived corresponding to the weave analysis. It involves in making the harness / ends in two sections; one section is to increase the figuring capacity by scaling the harness and combining it with other section of simple stitching harnessing of ends. Hence, the new harness methodology has been named as ‘section-scale-stitch’ harnessing. The advantages of new SSS harnessing to weave figured twill damask have been recorded. It is observed that the new harnessing methodology has got the advantages like increased figuring capacity with the given jacquard, less strain on the ends and versatility to produce all range of products of twill damask. It is also found that the new harnessing is suitable to weave figured double cloth using interchanging double equal plain cloth, extra warp and extra weft weaving. -

Historic Costuming Presented by Jill Harrison

Historic Southern Indiana Interpretation Workshop, March 2-4, 1998 Historic Costuming Presented By Jill Harrison IMPRESSIONS Each of us makes an impression before ever saying a word. We size up visitors all the time, anticipating behavior from their age, clothing, and demeanor. What do they think of interpreters, disguised as we are in the threads of another time? While stressing the importance of historically accurate costuming (outfits) and accoutrements for first- person interpreters, there are many reasons compromises are made - perhaps a tight budget or lack of skilled construction personnel. Items such as shoes and eyeglasses are usually a sticking point when assembling a truly accurate outfit. It has been suggested that when visitors spot inaccurate details, interpreter credibility is downgraded and visitors launch into a frame of mind to find other inaccuracies. This may be true of visitors who are historical reenactors, buffs, or other interpreters. Most visitors, though, lack the heightened awareness to recognize the difference between authentic period detailing and the less-than-perfect substitutions. But everyone will notice a wristwatch, sunglasses, or tennis shoes. We have a responsibility to the public not to misrepresent the past; otherwise we are not preserving history but instead creating our own fiction and calling it the truth. Realistically, the appearance of the interpreter, our information base, our techniques, and our environment all affect the first-person experience. Historically accurate costuming perfection is laudable and reinforces academic credence. The minute details can be a springboard to important educational concepts; but the outfit is not the linchpin on which successful interpretation hangs. -

14.2% Vote for President Occupations Are Now out of Order

\% F E B 1 9 8 0 Tetley Bittermen. Join’em. No. 2 1 9 Friday, 8th February, 1980 FREE 14.2% vote for President LOW TURNOUT CAUSES ANGER Members of the University Union Executive have said that they are “disgusted” with the turnout at this week’s elections for President and Deputy President. President Steve Aulsebrook called it “pathetic”, while General Secretary Ray Cohen commented, “ I’m as sick as a parrot; it is ------------------------------- -———------- pretty disgusting”. In the elections, which were by Hugh Bateson held over four days at the beginning of the week, only 1504 people voted, 14.2% of the total electorate. with 310. Mr. Goodman was as In the past, voting for the President annoyed with the turnout as Mr. has usually attracted about 33%. Shenton, he said, Last year, when Mr. Aulsebrook “ I hope the students get a better was elected, the poll was considered executive than they deserve. very low at 25%. Thousands, literally thousands of Mr. Cohen explained that con people used this Union on Monday siderable efforts had been made to and Tuesday lunch times and they ensure a high turnout this year, couldn’t even be bothered to pick “ Advertising this year was up a ballot paper for their own greater than for any other year” he Union and the way it is run” . said. He continued that for the first Ian Rosenthal commented, time voting had occurred in the “I am very upset that more halls of residence, to enable people people did’t take offence at what who do not frequent the Union to I was saying and vote to keep me vote. -

Week 3 the Woollen & Worsted Industries to 1780

Week 3 Dr Frances Richardson frances.richardson@conted. The woollen & ox.ac.uk https://open.conted.ox.ac.uk /series/manufactures- worsted industries industrial-revolution to 1780 Week 2 takeaways • Proto-industrialization theories give us some useful concepts for studying specific pre-factory manufacturing industries • More a framework than a predictive model • Artisan systems did not necessarily develop into putting-out systems • Proto-industry contained the seeds of its own demise • Although factory industrialization often grew out of proto-industry in the same area, some areas de-industrialized and industry spread to new areas • Other factors needed to explain changes, including marketing, industrial relations, and local politics Week 3 outline • Processes in woollen and worsted hand manufacture • Outline history – changing fashions, home demand and exports Wool comber • Organization of the industry in the West Country, Norwich and Yorkshire • How organisation and marketing affected success • How well different regions responded to changing fashion and demand Woollen cloth • Used carded, short-staple wool • Traditional from medieval period, predominated in Tudor exports • Types of cloth - broadcloth, kersey (lighter, less heavily fulled) • Export cloth high and medium quality – limited demand growth • Wool was sorted, willeyed, carded, spun, woven, fulled, finished – could involve raising nap, shearing, pressing, dyeing Broadcloth suit, 1705, VAM Worsted • Used combed, long-staple wool Lincoln longwool sheep • More suited to the Saxony -

Glossary of Terms

The Missing Chapter: Untold Stories of the African American Presence in the Mid-Hudson Valley Glossary of Terms Bay: A compartment in a barn, used fore storing hay or grain. Britches or Breeches: Short trousers, especially fastened below the knee. Breeches were originally made of leather, but were made of various materials. Buckskin: Leather made from a buck’s skin, could also refer to a thick smooth cotton or woolen cloth. Coating: A cloth used for making coats. Drab coloured: A dull brownish yellow or dull gray color. Felt: A fabric made of wool and hair. Fife: A small high-pitched flute without keys, often used in military and marching bands. Fustian: A coarse sturdy cloth of a cotton-linen blend; any durable fabric with a raised nap made mainly from cotton, for example, corduroy or moleskin. Gaol: is an early Modern English spelling for jail, with the same pronunciation and meaning of a place of legal detention. Grogram: A rough fabric of silk and wool with a diagonal weave. High Dutch: An eighteenth century term for German. Homespun: Spun or woven in the home; a plain coarse woolen cloth made of homespun yarn. Instant (inst.): The current calendar month. Inventory: a detailed list of things in one’s view or possession; especially, a regular survey of all goods and materials in stock. Linsey Woolsey: A coarse fabric of cotton or linen woven with wool. Low Dutch: used to signify those persons of Netherlandish descent. Manchester velvet: A fine cotton used in making dresses. The Missing Chapter: Untold Stories of the African American Presence in the Mid-Hudson Valley Nanekeen: A sturdy yellow or buff cotton cloth.