Tom Wilson Phd Commentary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Piano Recital Prize and Arnold Schoenberg

1 Welcome to Summer 2015 at the RNCM As Summer 2015 approaches, the RNCM Our orchestral concerts are some of our most prepares for one of its most monumental concerts colourful ones, and more fairytales come to life to date. This is an historic moment for the College with Kodaly’s Hary Janos and Bartók’s Miraculous and I am honoured and thrilled to be welcoming Mandarin as well as with an RNCM Family Day, Krzysztof Penderecki to conduct the UK première where we join forces with MMU’s Manchester of his magnificent Seven Gates of Jerusalem Children’s Book Festival to bring together a feast at The Bridgewater Hall in June. This will be of music and stories for all ages with puppetry, the apex of our celebration of Polish music, story-telling, live music and more. RNCM Youth very kindly supported by the Adam Mickiewicz Perform is back on stage with Bernstein’s award- Institute, as part of the Polska Music programme. winning musical On the Town, and our Day of Song brings the world of Cabaret to life. In a merging of soundworlds, we create an ever-changing kaleidoscope of performances, We present music from around the world with presenting one of our broadest programmes to Taiko Meantime Drumming, Taraf de Haïdouks, date. Starting with saxophone legend David Tango Siempre, fado singer Gisela João and Sanborn, and entering the world of progressive singer songwriters Eddi Reader, Thea Gilmore, fusion with Polar Bear, the jazz programme at Benjamin Clementine, Raghu Dixit, Emily Portman the RNCM collaborates once more with Serious and Mariana Sadovska (aka ‘The Ukranian as well as with the Manchester Jazz Festival to Bjork’). -

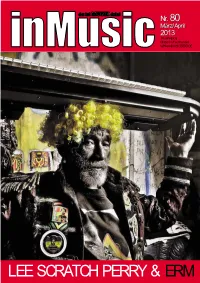

Lee Scratch Perry &

Nr. 80 März/April 2013 16.Jahrgang Gratis im Fachhandel WWW.INMUSIC2000.DE LEE SCRATCH PERRY & ERM inHard_inMusic_S1_S16 18.03.2013 3:49 Uhr Seite 16 Seite Uhr 3:49 18.03.2013 inHard_inMusic_S1_S16 MONATS DES CD LEE SCRATCH PERRY HELENE BLUM DAISY CHAPMAN TRYO MYTHOS & ERM Men med abne ojne Shameless Winter Ladilafé Surround Sound Evolution Humanicity Westpark Music/Indigo Songs & Whispers/Cargo Sony Music Sireena/Broken Silence Rubis Manag./Broken Silence ###### ##### ##### ##### ###### Melancholischer & fragiler Die britische Sängerin, Pia- In Frankreich sind Tryo seit Alle Liebhaber eines elek- Was für eine gelungene Folkpop aus Dänemark: nistin und Songwriterin 15 Jahren eine feste Größe tronisch getränkten Spa- Scheibe legt denn Reggae- Helene Blum sieht nicht nur Daisy Chapman stellt mit und können auf eine große cerock/Psychedelic-Sounds Urgestein Lee Scratch Perry sehr gut aus, sondern ist „Shameless Winter“ ihr Fangemeinde verweisen. können sich über die neue- hier vor? Die 10 Tracks zu auch eine ausgezeichnete bereits drittes Album vor. Mehr als 3mio Alben gingen ste Veröffentlichung von seiner neuen Platte „Huma- Sängerin und Songwriterin, Eine sehr empfehlenswerte dort bereits über die Mythos, der legendären nicity“ entstanden im letzten die in ihre 11 Songs (alle- Scheibe, die ich allen Lesern Ladentheke. Mit großer Tour Band um Stephan Kaske Jahr im Straßburger „Studio samt in dänischer Sprache nur ans Herz legen kann! Ihr und neuem Album nehmen freuen. Für den Hörer heißt Grenat“ zusammen mit dem - ich liebe das!) unglaublich ausdrucksstarker, leicht die 4 Herren nun auch die das, tief eintauchen in einen bekannten französischen viel Wärme, Sehnsucht und dunkler und emotionaler deutschen Musikhörer ins elektronisch verwobenen Produzententeam ERM Glaubwürdigkeit legt. -

Photo Needed How Little You

HOW LITTLE YOU ARE For Voices And Guitars BY NICO MUHLY WORLD PREMIERE PHOTO NEEDED Featuring ALLEGRO ENSEMBLE, CONSPIRARE YOUTH CHOIRS Nina Revering, conductor AUSTIN CLASSICAL GUITAR YOUTH ORCHESTRA Brent Baldwin, conductor HOW LITTLE YOU ARE BY NICO MUHLY | WORLD PREMIERE TEXAS PERFORMING ARTS PROGRAM: PLEASESEEINSERTFORTHEFIRSTHALFOFTHISEVENING'SPROGRAM ABOUT THE PROGRAM Sing Gary Barlow & Andrew Lloyd Webber, arr. Ed Lojeski From the first meetings aboutHow Little Renowned choral composer Eric Whitacre You Are, the partnering organizations was asked by Disney executives in 2009 Powerman Graham Reynolds knew we wanted to involve Conspirare to compose for a proposed animated film Youth Choirs and Austin Classical Guitar based on Rudyard Kipling’s beautiful story Libertango Ástor Piazzolla, arr. Oscar Escalada Youth Orchestra in the production and are The Seal Lullaby. Whitacre submitted this Austin Haller, piano delighted that they are performing these beautiful, lyrical work to the studios, but was works. later told that they decided to make “Kung The Seal Lullaby Eric Whitacre Fu Panda” instead. With its universal message issuing a quiet Shenandoah Traditional, arr. Matthew Lyons invitation, Gary Barlow and Andrew Lloyd In honor of the 19th-century American Webber’s Sing, commissioned for Queen poetry inspiring Nico Muhly’s How Little That Lonesome Road James Taylor & Don Grolnick, arr. Matthew Lyons Elizabeth’s Diamond Jubilee in 2012, brings You Are, we chose to end the first half with the sweetness of children’s voices to brilliant two quintessentially American folk songs Featuring relief. arranged for this occasion by Austin native ALLEGRO ENSEMBLE, CONSPIRARE YOUTH CHOIRS Matthew Lyons. The haunting and beautiful Nina Revering, conductor Powerman by iconic Austin composer Shenandoah precedes James Taylor’s That Graham Reynolds was commissioned Lonesome Road, setting the stage for our AUSTIN CLASSICAL GUITAR YOUTH ORCHESTRA by ACG for the YouthFest component of experience of Muhly’s newest masterwork. -

The Menstrual Cramps / Kiss Me, Killer

[email protected] @NightshiftMag NightshiftMag nightshiftmag.co.uk Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 279 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2018 “What was it like getting Kate Bush’s approval? One of the best moments ever!” photo: Oli Williams CANDYCANDY SAYSSAYS Brexit, babies and Kate Bush with Oxford’s revitalised pop wonderkids Also in this issue: Introducing DOLLY MAVIES Wheatsheaf re-opens; Cellar fights on; Rock Barn closes plus All your Oxford music news, previews and reviews, and seven pages of local gigs for October NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshiftmag.co.uk host a free afternoon of music in the Wheatsheaf’s downstairs bar, starting at 3.30pm with sets from Adam & Elvis, Mark Atherton & Friends, Twizz Twangle, Zim Grady BEANIE TAPES and ALL WILL BE WELL are among the labels and Emma Hunter. releasing new tapes for Cassette Store Day this month. Both locally- The enduring monthly gig night, based labels will have special cassette-only releases available at Truck run by The Mighty Redox’s Sue Store on Saturday 13th October as a series of events takes place in record Smith and Phil Freizinger, along stores around the UK to celebrate the resurgence of the format. with Ainan Addison, began in Beanie Tapes release an EP by local teenage singer-songwriter Max October 1991 with the aim of Blansjaar, titled `Spit It Out’, as well as `Continuous Play’, a compilation recreating the spirit of free festivals of Oxford acts featuring 19 artists, including Candy Says; Gaz Coombes; in Oxford venues and has proudly Lucy Leave; Premium Leisure and Dolly Mavies (pictured). -

Highly Anticipated Non-Profit Music Venue in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, Announces Opening, Curators, Programming Details and a New Name

For Immediate Release May 8, 2015 Press Contacts: Blake Zidell, John Wyszniewski and Ron Gaskill at Blake Zidell & Associates: 718.643.9052, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. HIGHLY ANTICIPATED NON-PROFIT MUSIC VENUE IN WILLIAMSBURG, BROOKLYN, ANNOUNCES OPENING, CURATORS, PROGRAMMING DETAILS AND A NEW NAME Beginning in October, National Sawdust (Formerly Original Music Workshop) Will Provide Composers and Musicians a State-of-the-Art Home for the Creation of New Work and Will Give Audiences and a Place to Discover Genre-Spanning Music at Accessible Ticket Prices Curators to Include Composers Anna Clyne, Bryce Dessner, David T. Little and Nico Muhly; Pianists Simone Dinnerstein and Anne Marie McDermott; Vocalists Helga Davis, Theo Bleckmann and Magos Herrera; and Violinists Miranda Cuckson and Tim Fain Groups and Artists in Residence to Include Brooklyn Rider, Glenn Kotche (Wilco), Alicia Hall Moran and Zimbabwe’s Netsayi Venue Partners and Collaborators Range from Carnegie Hall's Weill Music Institute and the New York Philharmonic’s CONTACT! to Stanford University and Williamsburg-Based El Puente Center for Arts and Culture National Sawdust +, Created by Elena Park, Will Include National Sawdust Talks as well as Performance Series that Offer Leading Directors and Writers, from Richard Eyre to Michael Mayer, a Platform to Share Their Musical Passions Opening Concerts in October to Feature Terry Riley, John Zorn, Roomful of Teeth, Nico Muhly, Bryce Dessner, Fence Bower Jon Rose, Throat Singer Tanya Tagaq and Others Brooklyn, NY (May 7, 2015) - The non-profit National Sawdust, formerly known as Original Music Workshop, is pleased to announce that its highly anticipated, state-of-the-art, Williamsburg, Brooklyn venue will open this fall. -

URMC V118n83 20091210.Pdf (9.241Mb)

THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN Fort Collins, Colorado COLLEGIAN Volume 118 | No. 8 T D THE STUDENT VOICE OF COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1891 B ASCS ICE, ICE, BABY BOG Leg. a airs director wants student voice on governing board B KIRSTEN SIVEIRA The Rocky ountain Collegian After CSU’s governing board decided to ban concealed weapons on campus, spark- TODAYS IG ing intense controversy student leaders said Wednesday that there must be a student vot- 25 degrees ing member on the board because its mem- bers refuse to listen to students. So far this season, CSU To secure that voting member, Associ- has received a total of 44.2 ated Students of CSU Director of Legislative inches of snow with fi ve full YEAR SEASONA Affairs Matt Worthington drafted a resolu- months of the snow season TOTA IN INCES tion that would allow state leaders to appoint still ahead, according to re- a student to vote on the CSU System Board search from the Department 1 9 9 9 - 2 0 0 0 : 3 . of Governors. The ASCSU Senate moved his of Atmospheric Science. 2 0 0 0 - 2 0 0 1 : 5 resolution to committee Wednesday night. Even if the city receives 2 0 0 1 - 2 0 0 2 : 4 4 .1 ASCSU President Dan Gearhart and CSU- no more snow this winter, 2 0 0 2 - 2 0 0 3 : 1. Pueblo student government President Steve Fort Collins has already re- 2 0 0 3 - 2 0 0 4 : 9 .1 Titus both currently sit on the BOG as non- ceived more snow than in six 2 0 0 4 - 2 0 0 5 : 5 . -

Concerts from the Library of Congress 2012-2013

Concerts from the Library of Congress 2012-2013 LIBRARY LATE ACME & yMusic Friday, November 30, 2012 9:30 in the evening sprenger theater Atlas performing arts center The McKim Fund in the Library of Congress was created in 1970 through a bequest of Mrs. W. Duncan McKim, concert violinist, who won international prominence under her maiden name, Leonora Jackson; the fund supports the commissioning and performance of chamber music for violin and piano. Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. Please take note: UNAUTHORIZED USE OF PHOTOGRAPHIC AND SOUND RECORDING EQUIPMENT IS STRICTLY PROHIBITED. PATRONS ARE REQUESTED TO TURN OFF THEIR CELLULAR PHONES, ALARM WATCHES, OR OTHER NOISE-MAKING DEVICES THAT WOULD DISRUPT THE PERFORMANCE. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. Please recycle your programs at the conclusion of the concert. THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Atlas Performing Arts Center FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 2012, at 9:30 p.m. THE mckim Fund In the Library of Congress American Contemporary Music Ensemble Rob Moose and Caleb Burhans, violin Nadia Sirota, viola Clarice Jensen, cello Timothy Andres, piano CAROLINE ADELAIDE SHAW Limestone and Felt, for viola and cello DON BYRON Spin, for violin and piano (McKim Fund Commission) JOHN CAGE (1912-1992) String Quartet in Four Parts (1950) Quietly Flowing Along Slowly Rocking Nearly Stationary Quodlibet MICK BARR ACMED, for violin, viola and cello Intermission *Meet the Artists* yMusic Alex Sopp, flutes Hideaki Aomori, clarinets C.J. -

You Wanted Columns? You Got 'Em>>

FOR FANS OF MUSIC & THOSE WHO MAKE IT Issue 10 • FREE • athensblur.com THESE UNITED STATES • MAD WHISKEY GRIN • BLITZEN TRAPPER • THE DELFIELDS • MEIKO • JANELLE MONAE • TRANCES ARC • DODD FERRELLE • CRACKER & MORE!!! ZERO 7 Acclaimed electronic duo gets haunted on album number four TORTOISE Inspiration be damned — Tortoise soldiers on WHEN You’rE HOT Bradley Cooper’s sizzling Hollywood ride HEART LIFE AT THE SPEED IN haND OF TWEET The latest social media After an eight-year absence, an outlet is changing the music industry, for energized Circulatory System better or for worse returns with a new album VENUE VENTURES Four clubs lead the way into a changing face of Athens music spots YOU WANTED COLUMNS? YOU GOt ‘eM>> SIGN UP AT www.gamey.com/print ENTER CODE: NEWS65 *New members only. Free trial valid in the 50 United States only, and cannot be combined with any other offer. Limit one per household. First-time customers only. Internet access and valid payment method required to redeem offer. GameFly will begin to bill your payment method for the plan selected at sign-up at the completion of the free trial unless you cancel prior to the end of the free trial. Plan prices subject to change. Please visit www.gamey.com/terms for complete Terms of Use. Free Trial Offer expires 12/31/2010. (44) After an eight-year absence, an energized Circulatory System returns with a new HEART album. by Ed Morales IN HAND photos by Jason Thrasher (40) (48) Acclaimed electronic duo Zero 7 gets “haunted” The latest social making album number media outlet is four. -

1978-05-22 P MACHO MAN Village People RCA 7" Vinyl Single 103106 1978-05-22 P MORE LIKE in the MOVIES Dr

1978-05-22 P MACHO MAN Village People RCA 7" vinyl single 103106 1978-05-22 P MORE LIKE IN THE MOVIES Dr. Hook EMI 7" vinyl single CP 11706 1978-05-22 P COUNT ON ME Jefferson Starship RCA 7" vinyl single 103070 1978-05-22 P THE STRANGER Billy Joel CBS 7" vinyl single BA 222406 1978-05-22 P YANKEE DOODLE DANDY Paul Jabara AST 7" vinyl single NB 005 1978-05-22 P BABY HOLD ON Eddie Money CBS 7" vinyl single BA 222383 1978-05-22 P RIVERS OF BABYLON Boney M WEA 7" vinyl single 45-1872 1978-05-22 P WEREWOLVES OF LONDON Warren Zevon WEA 7" vinyl single E 45472 1978-05-22 P BAT OUT OF HELL Meat Loaf CBS 7" vinyl single ES 280 1978-05-22 P THIS TIME I'M IN IT FOR LOVE Player POL 7" vinyl single 6078 902 1978-05-22 P TWO DOORS DOWN Dolly Parton RCA 7" vinyl single 103100 1978-05-22 P MR. BLUE SKY Electric Light Orchestra (ELO) FES 7" vinyl single K 7039 1978-05-22 P HEY LORD, DON'T ASK ME QUESTIONS Graham Parker & the Rumour POL 7" vinyl single 6059 199 1978-05-22 P DUST IN THE WIND Kansas CBS 7" vinyl single ES 278 1978-05-22 P SORRY, I'M A LADY Baccara RCA 7" vinyl single 102991 1978-05-22 P WORDS ARE NOT ENOUGH Jon English POL 7" vinyl single 2079 121 1978-05-22 P I WAS ONLY JOKING Rod Stewart WEA 7" vinyl single WB 6865 1978-05-22 P MATCHSTALK MEN AND MATCHTALK CATS AND DOGS Brian and Michael AST 7" vinyl single AP 1961 1978-05-22 P IT'S SO EASY Linda Ronstadt WEA 7" vinyl single EF 90042 1978-05-22 P HERE AM I Bonnie Tyler RCA 7" vinyl single 1031126 1978-05-22 P IMAGINATION Marcia Hines POL 7" vinyl single MS 513 1978-05-29 P BBBBBBBBBBBBBOOGIE -

Sonntags Im Bistro Grottino, Sommer 2015 (16.59H Bis Ca

Sonntags im Bistro Grottino, Sommer 2015 (16.59h bis ca. 19.08h) Set vom 7.6. Real Estate: Past Lives Department of Eagles: No One Does It Like You Unknown Mortal Orchestra: So Good… Ruby Suns: Oh Mojave The Congos: Fisherman The Upsetters: Big Gal Sally Beastie Boys: Song for the Man Captain Beefheart: Abba Zaba Destroyer: Del Monton Magnetic Fields: The Luckiest Guy… Beck: Black Tambourine Can: Halleluhwah Dorothy Collins: Lightworks (Raymond Scott) Erykah Badu: Soldier Digable Planets: Black Ego Calexico: Not Even Stevie Nicks Avey Tare's Slasher Flicks: Little Fang Panda Bear: Boys Latin Deerhoof: Super Duper Rescue Head Daniel Johnston: The Sun Shines Down Gil Scott Heron: Home Is Where the Hatred Is Timmy Thomas: Why Can't We Live Together The Four Tops: Baby I Need Your Loving Matthew E. White: Golden Robes William Onyeabor: Atomic Bomb Connan Mockasin: Megumi the Milkyway Above Django Django: Found You Atlas Sound: Walkabout Islands: Jogging Gorgeous Summer Tame Impala: Let it Happen The Notwist: Gloomy Planets Dan Deacon: Feel the Lightning Tocotronic: Spiralen Destroyer: Kaputt Set vom 14.6. Simone White: Flowers in May Beach House: Walk in the Park Peaking Lights: All the Sun That Shines The Slits: Man Next Door Jaako Eino Kalevi: Deeper Shadows Sisyphus: Lion's Share The Soundcarriers: So Beguiled Toro y Moi: Empty Nesters Kyu Sakamoto: Sukiyaki Homeboy Sandman: Holiday (Kosi Edit) Real Estate: Crime Devendra Banhart: Won't You Come Over Yo La Tengo: Automatic Doom Caribou: Melody Day Chris Cohen: Don't Look Today Unknown Mortal Orchestra: Can't Keep Checking My Phone John Cale: Hanky Panky Nohow Mac DeMarco: Let Her Go Girls: Oh So Protective One Stereolab: Fuses Beck: Tropicalia Cloud One: Atmosphere Strut Remix 1979 Cliff King Solomon: But Officer! Ariel Pink: Baby Frank Ocean: Forrest Gump Animal Collective: Rosie Oh Alexis Taylor: Am I Not A Soldier? Freddie Gibbs & Madlib: Shame (Instrumental) Arthur Russell: That's Us / Wild Combination The Streets: Never Went to Church Jacques Palminger: Wann strahlst Du? Dick Justice: Henry Lee Set vom 21.6. -

A Obra-Prima De Um Sacana

Sexta-feira 28 Agosto 2009 www.ipsilon.pt Quentin Tarantino, novo filme ESTE SUPLEMENTO FAZ PARTE INTEGRANTE DA EDIÇÃO Nº 7087 DO PÚBLICO, E NÃO PODE SER VENDIDO SEPARADAMENTE DO PÚBLICO, EDIÇÃO Nº 7087 INTEGRANTE DA PARTE FAZ ESTE SUPLEMENTO A obra-prima de um sacana NICOLAS GUERIN/CORBIS NICOLAS Hayao Miyazaki John Landis Mário Zambujal Fiery Furnaces Festival de Atenas e Epidauros Wavves em Dezembro por todos os caminhos das harmonias vocais) em Micachu inesperados para criar canções descalabro “who cares?” de ética “d.i.y.” e alto teor adoptado directamente do trauteável. Segundo anuncia o punk (ou da adolescência). Os e Wavves MySpace da banda de Mica Levi Wavves cantam coisas (Micachu) - onde já está intemporais como os “No hope para a disponível “Kwesachu”, kids” que não têm carro, nem “mixtape” criada em parceria miúda, nem emprego, e, com o músico e artista Kwes -, depois de dois concertos rentrée os Micachu passam pelo Plano portugueses cancelados em B, no Porto, dia 20 de Maio, consequência de uma São boas notícias para a rentrée Novembro, descendo até passagem desastrosa pelo ou, se quisermos ser Lisboa, à Galeria Zé dos Bois, no festival Primavera Sound – verdadeiramente precisos, para dia seguinte. “Misturar ecstasy, Valium e a pré-época natalícia. Quatro Um mês depois, chegarão os Xanax antes de tocar em Flash concertos e duas bandas, Wavves de Nathan Williams, frente de milhares de pessoas Micachu & The Shapes e miúdo aborrecido com a vida na foi uma das piores decisões Wavves, daquelas que, para o Califórnia que transformou o que já tomei”, foram as bem ou para o mal, vale mesmo aborrecimento em matéria palavras imortais de Nathan a pena ver neste preciso inspiradora. -

20Th Century Women by Mike Mills EXT

20th Century Women by Mike Mills EXT. OCEAN - DAY High overhead shot looking down on the Pacific Ocean. TITLE: SANTA BARBARA, 1979. EXT. SANTA BARBARA - VONS PARKING LOT - DAY WIDE ON a plume of black smoke rising high into the air. CLOSER ON a 1965 Ford Galaxy engulfed in flames. DOROTHEA (55, short grey hair, Amelia Earhart androgyny) and JAMIE (15, New-Wave/Punk) jog their shopping cart toward the commotion, stunned to find their car in flames. Dorothea looks at the car and then at her son Jamie, concerned. People run for help. Sirens in the background. DOROTHEA (V.O.) That was my husband’s Ford Galaxy. We drove Jamie home from the hospital in that car. JAMIE (V.O.) VISUALS My mom was 40 when she had 1. BABY IN ISOLETTE me. Everyone told her she was too old to be a mother. DOROTHEA (V.O.) VISUALS I put my hand through the 2. DOROTHEA’S HAND OPENING little window, and he’d ISOLETTE WINDOW AND PUTTING squeeze my finger, and I’d HAND THROUGH 3. BABY’S tell him life was very big, FINGERS HOLDING HAND 4. STARS and unknown; IN SPACE JAMIE (V.O.) VISUALS And she told me that there 5. MUYBRIDGE FOOTAGE OF were animals and sky and ANIMALS 6. STILL OF THE SKY cities, 7. CITY FROM DOROTHEA’S ERA DOROTHEA (V.O.) VISUALS Music, movies. He’d fall in 8. BACK TO DOROTHEA’S HAND love, have his own children, OPENING ISOLETTE WINDOW AND have passions, have meaning, PUTTING HAND THROUGH 9.