Copyright by Colin M. Mason 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeing (For) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Benjamin Park, "Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623644. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t267-zy28 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing (for) Miles: Jazz, Race, and Objects of Performance Benjamin Park Anderson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, College of William and Mary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies Program College of William and Mary May 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Benjamin Park Anderson Approved by T7 Associate Professor ur Knight, American Studies Program The College -

Jazzletter P-Q Ocrober 1986 P 5Jno;..1O

Jazzletter P-Q ocrober 1986 P 5jNo;..1o . u-1'!-an J.R. Davis,.Bill Davis, Rusty Dedrick, Buddy DeFranco, Blair The Readers . Deiermann, Rene de Knight,‘ Ron Della Chiesa (WGBH), As of August 25, I986, the JazzIetrer’s readers were: Louise Dennys, Joe Derise, Vince Dellosa, Roger DeShon, Michael Abene, John Abbott, Mariano F. Accardi, Harlan John Dever, Harvey Diamond, Samuel H. Dibert’, Richard Adamcik, Keith Albano, Howard Alden, Eleanore Aldrich, DiCarlo, Gene DiNovi, Victor DiNovi, Chuck Domanico, Jeff Alexander, Steve Allen, Vernon Alley, Alternate and Arthur Domaschenz, Mr. and Mrs. Steve Donahue, William E. Independent Study Program, Bill Angel, Alfred Appel J r, Ted Donoghue, Bob Dorough, Ed Dougherty, Hermie Dressel, Len Arenson, Bruce R. Armstrong, Jim Armstrong, Tex Arnold, Dresslar, Kenny Drew, Ray Drummond, R.H. Duffield, Lloyd Kenny Ascher, George Avakian, Heman B. Averill, L. Dulbecco, Larry Dunlap, Marilyn Dunlap, Brian Duran, Jean Bach, Bob Bain, Charles Baker (Kent State University Eddie Duran, Mike Dutton (KCBX), ' School of Music), Bill Ballentine, Whitney Balliett, Julius Wendell Echols, Harry (Sweets) Edison,Jim_Eigo, Rachel Banas, Jim Barker, Robert H. Barnes, Charlie Barnet, Shira Elkind-Tourre, Jack Elliott, Herb Ellis, Jim Ellison, Jack r Barnett, Jeff Barr, E.M. Barto Jr, Randolph Bean, Jack Ellsworth (WLIM), Matt Elmore (KCBX FM), Gene Elzy Beckerman, Bruce B. Bee, Lori Bell, Malcolm Bell Jr, Carroll J . (WJR), Ralph Enriquez, Dewey Emey, Ricardo Estaban, Ray Bellis MD, Mr and Mrs Mike Benedict, Myron Bennett, Dick Eubanks (Capital University Conservatory of Music), Gil Bentley, Stephen C. Berens MD, Alan Bergman, James L. Evans, Prof Tom Everett (Harvard University), Berkowitz, Sheldon L. -

Brazil and Switzerland Plays Together to Celebrate Music

BRAZIL AND SWITZERLAND PLAYS TOGETHER TO CELEBRATE MUSIC At the end of May 2016 an alliance between Brazil and Switzerland aims to conquer Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, starting May 25 th . Both cities will host sessions joining Brazilian and foreign musicians during Switzerland meets Brazil. The event presented by Swissando and Montreux Jazz Festival , will have performances by bands Nação Zumbi and The Young Gods, as well as concerts at the Swissando Jazz Club, this place is inspired by the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland, which celebrates its 50 the edition this year, featuring emerging talents and icons from the Brazilian scene. “Music is a great way to celebrate friendship between countries. Thanks to the Montreux Jazz Festival and its founder, Claude Nobs, Brazilian music is well known in Switzerland and in Europe. Brazilian musicians having been invited there almost since the beginning of the Festival. Joining our forces here for this project is a perfect match!” says André Regli, Swiss Ambassador in Brazil. The most important meeting takes place on May 26 th at Cine Joia in São Paulo, and on the 27 th, at Circo Voador, in Rio, with a joint performance between Brazilian band Nação Zumbi and Swiss group The Young Gods. The show will be a taste of what they are preparing for the 50 th edition of the Montreux Jazz Festival, which will take place in July in Switzerland. Besides the meeting of the two bands, who go through Circo Voador during Switzerland meets Brazil, will be able to see an exhibition honoring some Jazz Festival Montreux icons, including Brazilian legend. -

Annual AT&T San Jose Jazz Summer Fest Friday, August 12

***For Immediate Release*** 22nd Annual AT&T San Jose Jazz Summer Fest Friday, August 12 - Sunday, August 14, 2011 Plaza de Cesar Chavez Park, Downtown San Jose, CA Ticket Info: www.jazzfest.sanjosejazz.org Tickets: $15 - $20, Children Under 12 Free "The annual San Jose Jazz [Summer Fest] has grown to become one of the premier music events in this country. San Jose Jazz has also created many educational programs that have helped over 100,000 students to learn about music, and to become better musicians and better people." -Quincy Jones "Folks from all around the Bay Area flock to this giant block party… There's something ritualesque about the San Jose Jazz [Summer Fest.]" -Richard Scheinan, San Jose Mercury News "San Jose Jazz deserves a good deal of credit for spotting some of the region's most exciting artists long before they're headliners." -Andy Gilbert, San Jose Mercury News "Over 1,000 artists and 100,000 music lovers converge on San Jose for a weekend of jazz, funk, fusion, blues, salsa, Latin, R&B, electronica and many other forms of contemporary music." -KQED "…the festival continues to up the ante with the roster of about 80 performers that encompasses everything from marquee names to unique up and comers, and both national and local acts...." -Heather Zimmerman, Silicon Valley Community Newspapers San Jose, CA - June 15, 2011 - San Jose Jazz continues its rich tradition of presenting some of today's most distinguished artists and hottest jazz upstarts at the 22nd San Jose Jazz Summer Fest from Friday, August 12 through Sunday, August 14, 2011 at Plaza de Cesar Chavez Park in downtown San Jose, CA. -

Le Montreux Jazz Festival Présente Le Dispositif De Sa 55E Édition Conforme Aux Contraintes De La Pandémie

Montreux, le 28 juin 2021 COMMUNIQUÉ DE PRESSE Le Montreux Jazz Festival présente le dispositif de sa 55e édition conforme aux contraintes de la pandémie Les organisateurs proposent une 55e édition du Montreux Jazz Festival adaptée à la situation en lien avec l’épidémie de COVID-19. Il s’agit d’une édition largement réduite, sans animation hors périmètre, et avec un plan de protection sanitaire validé par l’Etat-major cantonal de conduite. Le Chef d’Etat-major cantonal a donné l’autorisation au MJF 2021 de se dérouler conformément au cadre légal en vigueur. La situation sanitaire étant en Suisse et dans le canton de Vaud totalement sous contrôle et la vacci- nation avancée, la première grande manifestation se déroulant sur territoire vaudois peut être autorisée. Si le res- pect strict des règles sanitaires mises en œuvre par les organisateurs permet de limiter les risques, il est important de continuer à faire appel à la responsabilité individuelle en appliquant les gestes barrières. Le plan de protection sanitaire du MJF a été élaboré selon l’Ordonnance sur les mesures destinées à lutter contre l’épidémie du Covid-19 en situation particulière, du 23 juin 2021 et selon l’étape d’assouplissement V, entrée en vigueur le 26 juin 2021. Il se base également sur le Plan de protection édité par l’EMCC applicable dans le cadre de l’organisation de grandes manifestations dès le 26 juin 2021. La stratégie générale du MJF repose sur la définition de zones réduites en capacité (capacité totale du site de 1’470 cette année, versus les 15’000 personnes par jour durant une édition en situation normale), et sur la maîtrise de chaque périmètre en termes de capacité et de traçabilité du public (découpage hermétique en secteurs, ver- sus un site complètement ouvert pour l’offre gratuite durant une édition en situation normale). -

June 2020 Volume 87 / Number 6

JUNE 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 6 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

The Recordings

Appendix: The Recordings These are the URLs of the original locations where I found the recordings used in this book. Those without a URL came from a cassette tape, LP or CD in my personal collection, or from now-defunct YouTube or Grooveshark web pages. I had many of the other recordings in my collection already, but searched for online sources to allow the reader to hear what I heard when writing the book. Naturally, these posted “videos” will disappear over time, although most of them then re- appear six months or a year later with a new URL. If you can’t find an alternate location, send me an e-mail and let me know. In the meantime, I have provided low-level mp3 files of the tracks that are not available or that I have modified in pitch or speed in private listening vaults where they can be heard. This way, the entire book can be verified by listening to the same re- cordings and works that I heard. For locations of these private sound vaults, please e-mail me and I will send you the links. They are not to be shared or downloaded, and the selections therein are only identified by their numbers from the complete list given below. Chapter I: 0001. Maple Leaf Rag (Joplin)/Scott Joplin, piano roll (1916) listen at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9E5iehuiYdQ 0002. Charleston Rag (a.k.a. Echoes of Africa)(Blake)/Eubie Blake, piano (1969) listen at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R7oQfRGUOnU 0003. Stars and Stripes Forever (John Philip Sousa, arr. -

Luther Johnson – Telarc.Com Luther “Guitar Junior” Johnson Is One of the Premier Blues Artists to Emerge from Chicago's

Luther Johnson – telarc.com Luther “Guitar Junior” Johnson is one of the premier blues artists to emerge from Chicago’s music scene. Hailing from Itta Bena, Mississippi, Johnson arrived in Chicago in the mid-fifties a young man. At around the same time, the West Side guitar style, a way of playing alternating stinging single-note leads with powerful distorted chords, was being created mostly by Magic Sam and Otis Rush. Originally developed because their small bands could not afford both lead and rhythm guitar players, this style grew into an important contribution to modern blues and rock, influencing such notables as Eric Clapton and Mark Knopfler. Johnson served a long sideman apprenticeship with both Magic Sam and Muddy Waters, while developing into a strong performer in his own right. Today, Luther is widely considered the foremost proponent of the West Side guitar style and the heir apparent to the late Magic Sam’s West Side throne. Luther Johnson first gained an international reputation as a guitarist and vocalist with Muddy Waters’ band, touring the U.S., Europe, Japan and Australia from 1973-79. Given the opportunity to front the band on his featured tunes in each show, Johnson’s super-charged performances consistently thrilled audiences in the world’s leading concert halls, including Carnegie Hall, Kennedy Center and Radio City Music Hall as well as at music festivals in Newport, Antibes, New Orleans and countless others. During his association with Muddy Waters, Johnson also shared the stage with The Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton, The Allman Brothers and Johnny Winter. -

Notre Dame Collegiate Jazz Festival Program, 1981

Archives of the University of Notre Dame Archives of the University of Notre Dame .. ~@~@@@@@~@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@~~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ MUSIC, ENTERTAINMENT & MORE. .. ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ o=oa ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ FOR THE BEST ENTERTAINMENT: ~ ~ in recorded sounds - ~ ~ JUST FOR THE RECORD ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ in live music - ~ Festival Staff ~ ~e ~ Chairman Tim Griffin ~ ~l( ~ Assistant Kevin Bauer Advertising ......................................................... .. Tom Rosshirt ~ UVlUSIC BOX AfB ~ Assistant Mike Mlynski Applications Jane Andersen Assistant Margie Smith ~ ~. ~ Graphics ........................................................... .. Sandy Pancoe Artists Pat Brunner, Jeff Loustau ~ in Mishawaka ~ High School Festival. ....................................... .. Bob O'Donnell, Joe Staudt ~ ~ ~ Master of Ceremonies .............................................. .. Barry Stevens @ Photography Cathy Donovan, Tim Griffin, Helen Odar . ~ ~ ~ Prizes ...................... James Dwyer Assistants. ........................................ .. Veronica Crosson, Vivian Sierra ~ Enjoy the best of both worlds, ! Production .. .......................................................... Kevin Magers Program Tom Krueger ~ with the best of people! --- ~ Assistants ........................ .. Scott Erbs, Tim Keyes, Scott O'Grady, Doug Ventura ~ ~ Publicity ....................................•........................ Mary Murphy ~ o Assistants Lynn Van Housen, John McBride, Lisa Scapellati ~ J F T R (1leUVlUSIC BOX ~ Security Ron Merriweather -

Paul Mccartney's

THE ULTIMATE HYBRID DRUMKIT FROM $ WIN YAMAHA VALUED OVER 5,700 • IMAGINE DRAGONS • JOEY JORDISON MODERNTHE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE DRUMMERJANUARY 2014 AFROBEAT 20DOUBLE BASS SECRETS PARADIDDLE PATTERNS MILES ARNTZEN ON TONY ALLEN CUSTOMIZE YOUR KIT WITH FOUND METAL ED SHAUGHNESSY 1929–2013 Paul McCartney’s Abe Laboriel Jr. BOOMY-LICIOUS MODERNDRUMMER.com + BENNY GREB ON DISCIPLINE + SETH RAUSCH OF LITTLE BIG TOWN + PEDRITO MARTINEZ PERCUSSION SENSATION + SIMMONS SD1000 E-KIT AND CRUSH ACRYLIC DRUMSET ON REVIEW paiste.com LEGENDARY SOUND FOR ROCK & BEYOND PAUL McCARTNEY PAUL ABE LABORIEL JR. ABE LABORIEL JR. «2002 cymbals are pure Rock n' Roll! They are punchy and shimmer like no other cymbals. The versatility is unmatched. Whether I'm recording or reaching the back of a stadium the sound is brilliant perfection! Long live 2002's!» 2002 SERIES The legendary cymbals that defined the sound of generations of drummers since the early days of Rock. The present 2002 is built on the foundation of the original classic cymbals and is expanded by modern sounds for today‘s popular music. 2002 cymbals are handcrafted from start to finish by highly skilled Swiss craftsmen. QUALITY HAND CRAFTED CYMBALS MADE IN SWITZERLAND Member of the Pearl Export Owners Group Since 1982 Ray Luzier was nine when he first told his friends he owned Pearl Export, and he hasn’t slowed down since. Now the series that kick-started a thousand careers and revolutionized drums is back and ready to do it again. Pearl Export Series brings true high-end performance to the masses. Join the Pearl Export Owners Group. -

Harold MABERN: Teo MACERO

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ Harold MABERN: "Workin' And Wailin'" Virgil Jones -tp,flh; George Coleman -ts; Harold Mabern -p; Buster Williams -b; Leo Morris -d; recorded June 30, 1969 in New York Leo Morris aka Idris Muhammad 101615 A TIME FOR LOVE 4.54 Prest PR7687 101616 WALTZING WESTWARD 9.26 --- 101617 I CAN'T UNDERSTAND WHAT I SEE IN YOU 8.33 --- 101618 STROZIER'S MODE 7.58 --- 101619 BLUES FOR PHINEAS 5.11 --- "Greasy Kid Stuff" Lee Morgan -tp; Hubert Laws -fl,ts; Harold Mabern -p; Boogaloo Joe Jones -g; Buster Williams -b; Idriss Muhammad -d; recorded January 26, 1970 in New York 101620 I WANT YOU BACK 5.30 Prest PR7764 101621 GREASY KID STUFF 8.23 --- 101622 ALEX THE GREAT 7.20 --- 101623 XKE 6.52 --- 101624 JOHN NEELY - BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE 8.33 --- 101625 I HAVEN'T GOT ANYTHING BETTER TO DO 6.04 --- "Remy Martin's New Years Special" James Moody Trio: Harold Mabern -p; Todd Coleman -b; Edward Gladden -d; recorded December 31, 1984 in Sweet Basil, New York it's the rhythm section of James Moody Quartet 99565 YOU DON'T KNOW WHAT LOVE IS 13.59 Aircheck 99566 THERE'S NO GREEATER LOVE 10.14 --- 99567 ALL BLUES 11.54 --- 99568 STRIKE UP THE BAND 13.05 --- "Lookin' On The Bright Side" Harold Mabern -p; Christian McBride -b; Jack DeJohnette -d; recorded February and March 1993 in New York 87461 LOOK ON THE BRIGHT SIDE 5.37 DIW 614 87462 MOMENT'S NOTICE 5.25 --- 87463 BIG TIME COOPER 8.04 --- 87464 AU PRIVAVE -

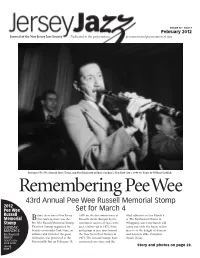

Rememberingpeewee

Volume 40 • Issue 2 February 2012 Journal of the New Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz. Portrait of Pee Wee Russell, Dave Tough, and Max Kaminsky at Eddie Condon's, New York City c. 1946-48. Photo by William Gottlieb. Remembering PeeWee 43rd Annual Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp 2012 Pee Wee Set for March 4 Russell efore there was a New Jersey 1970 on the first anniversary of 43rd edition is set for March 4 Memorial B Jazz Society, there was the Russell’s death. Buoyed by the at The Birchwood Manor in Stomp Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp. enormous success of that event, Whippany, when five bands will SUNDAY, That first Stomp, organized by and a follow-up in 1971, Stine swing out with five hours of hot MARCH 4 Society co-founder Jack Stine, an and group of jazz fans formed jazz — to the delight of dancers Birchwood admirer and friend of the great the New Jersey Jazz Society in and listeners alike. Complete Manor clarinetist, was presented at the 1972. The annual Stomps have details inside. TICKETS ON SALE NOW. Martinsville Inn on February 15, continued ever since and the see ad Story and photos on page 28. page 7 New JerseyJazzSociety in this issue: NEW JERSEY JAZZ SOCIETY Prez Sez . 2 Bulletin Board . 2 NJJS Calendar . 3 Pee Wee Dance Lessons. 4 Mail Bag. 4 Jazz Trivia . 4 Prez Sez Editor’s Pick/Deadlines/NJJS Info . 6 Crow’s Nest . 50 By Frank Mulvaney President, NJJS New/Renewed Members .