Annual Recorders of the Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mothers Grimm Kindle

MOTHERS GRIMM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Danielle Wood | 224 pages | 01 Oct 2016 | Allen & Unwin | 9781741756746 | English | St Leonards, Australia Mothers Grimm PDF Book Showing An aquatic reptilian-like creature that is an exceptional swimmer. They have a temper that they control and release to become effective killers, particularly when a matter involves a family member or loved one. She took Nick to Weston's car and told Nick that he knew Adalind was upstairs with Renard, and the two guys Weston sent around back knew too. When Wu asks how she got over thinking it was real, she tells him that it didn't matter whether it was real, what mattered was losing her fear of it. Dick Award Nominee I found the characters appealing, and the plot intriguing. This wesen is portrayed as the mythological basis for the Three Little Pigs. The tales are very dark, and while the central theme is motherhood, the stories are truly about womanhood, and society's unrealistic and unfair expectations of all of us. Paperback , pages. The series presents them as the mythological basis for The Story of the Three Bears. In a phone call, his parents called him Monroe, seeming to indicate that it is his first name. The first edition contained 86 stories, and by the seventh edition in , had unique fairy tales. Danielle is currently teaching creative writing at the University of Tasmania. The kiss of a musai secretes a psychotropic substance that causes obsessive infatuation. View all 3 comments. He asks Sean Renard, a police captain, to endorse him so he would be elected for the mayor position. -

The Brothers Grimm and the Yearning for Home Maureen Clack University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year Returning to the Scene of the Crime: The Brothers Grimm and the Yearning for Home Maureen Clack University of Wollongong Clack, Maureen, Returning to the Scene of the Crime: The Brothers Grimm and the Yearning for Home, M.A. thesis, School of Journalism and Creative Writing, University of Wollongong, 2006. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/730 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/730 RETURNING TO THE SCENE OF THE CRIME: THE BROTHERS GRIMM AND THE YEARNING FOR HOME A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree MASTER OF ARTS (HONOURS) from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by MAUREEN CLACK, BACHELOR OF ARTS (HONOURS) FACULTY OF CREATIVE ARTS 2006 CERTIFICATION I, Maureen Clack, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Master of Arts (Honours), in the Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Maureen Clack 31 October 2006 CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Page viii INTRODUCTION Fairy Tales, Feminism, Forensic Science and Home 1 CHAPTER 1 Feminism v Fairy Tales 17 CHAPTER 2 Returning to the Scene of the Crime 37 Visual Artists and Childhood Trauma 43 Hansel and Gretel: A Forensic Analysis 67 CHAPTER 3 Home Sweet Home 73 Visual Artists and Memories of Home 95 CHAPTER 4 Defective Stories 111 CONCLUSION 153 LIST OF WORKS CITED 159 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Throughout the lengthy process of constructing the argument and the artworks that make up this thesis I have had generous support from the following members of staff in the Faculty of Creative Arts. -

Distribution and Genesis of Degeer Moraines: Insights from the New National Height Model

UNIVERSITY OF GOTHENBURG Department of Earth Sciences Geovetarcentrum/Earth Science Centre Distribution and genesis of DeGeer moraines: insights from the New National Height model Vera Bouvier Gribel ISSN 1400-3821 B850 Master of Science (120 credits) thesis Göteborg 2015 Mailing address Address Telephone Telefax Geovetarcentrum Geovetarcentrum Geovetarcentrum 031-786 19 56 031-786 19 86 Göteborg University S 405 30 Göteborg Guldhedsgatan 5A S-405 30 Göteborg SWEDEN University of Gothenburg |Vera Bouvier Content 1 Introduction -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 1.1 Aim .............................................................................................................................................. 1 2 Background --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 2.1 LiDAR .......................................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 DeGeer moraine - the landform ................................................................................................. 3 2.2.1 Terminology ....................................................................................................................... 3 2.2.2 Characteristics .................................................................................................................... 3 2.3 Related Landforms..................................................................................................................... -

Naturalism, the New Journalism, and the Tradition of the Modern American Fact-Based Homicide Novel

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. U·M·I University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml48106-1346 USA 3131761-4700 800!521-0600 Order Number 9406702 Naturalism, the new journalism, and the tradition of the modern American fact-based homicide novel Whited, Lana Ann, Ph.D. -

Introduction to GIA Modeling

Glacial isostatic adjustment - An introduction Holger Steffen With input from Martin Ekman, Martin Lidberg, Rebekka Steffen, Wouter van der Wal, Pippa Whitehouse and Patrick Wu EGSIEM Summer School Potsdam, Germany 13/09/2017 GRACE observation, trend after post-processing 2 1st EGSIEM GIA correction 3 GRACE observation, GIA corrected 4 Question: What word or term do you have in mind when you hear “Glacial Isostatic Adjustment”? Time & length scale of some geodynamic processes GIA vs. the World 8 Plan In case of questions, ask! ° A bit of “GIA” history ° Some physics ° Some applications ° Observations of GIA ° Some applications ° GRACE, of course Reference for historical development ° Cathles, L.M. (1975) The viscosity of the Earth’s mantle, Princeton Univ. Press. ° Lliboutry, L. (1998) The birth and development of the concept of Glacial-Isostasy, and its Modelling up to 1974 in Dynamics of the Ice Age Earth: a modern Perspective, Ed. P.Wu, TTP. ° Ekman, M. (2009) The Changing Level of the Baltic Sea during 300 Years: A Clue to Understanding the Earth, Summer Institute for Historical Geophysics, Åland Islands. Open Access Download: http://www.historicalgeophysics.ax/The%20Changing %20Level%20of%20the%20Baltic%20Sea.pdf ° Krüger, T. (2013) Discovering the Ice Ages. International Reception and Consequences for a Historical Understanding of Climate. Brill, Leiden. Northern Europe ca. 1635 (Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/73/Svecia%2C_Dania_et_ Norvegia%2C_Regna_Europ%C3%A6_Septentrionalia.jpg) Luleå city/harbour relocation -

The Tales of the Grimm Brothers in Colombia: Introduction, Dissemination, and Reception

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2012 The alest of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception Alexandra Michaelis-Vultorius Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Michaelis-Vultorius, Alexandra, "The alet s of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception" (2012). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 386. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE TALES OF THE GRIMM BROTHERS IN COLOMBIA: INTRODUCTION, DISSEMINATION, AND RECEPTION by ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: MODERN LANGUAGES (German Studies) Approved by: __________________________________ Advisor Date __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS 2011 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my parents, Lucio and Clemencia, for your unconditional love and support, for instilling in me the joy of learning, and for believing in happy endings. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This journey with the Brothers Grimm was made possible through the valuable help, expertise, and kindness of a great number of people. First and foremost I want to thank my advisor and mentor, Professor Don Haase. You have been a wonderful teacher and a great inspiration for me over the past years. I am deeply grateful for your insight, guidance, dedication, and infinite patience throughout the writing of this dissertation. -

Classification of Animals

Grade 3 Core Knowledge Language Arts® • Listening & Learning™ Strand Classification of Animals of Classification Tell It Again!™ Read-Aloud Anthology Read-Aloud Again!™ It Tell Classification of Animals Tell It Again!™ Read-Aloud Anthology Listening & Learning™ Strand GrAde 3 Core Knowledge Language Arts® Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. You are free: to Share — to copy, distribute and transmit the work to Remix — to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution — You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike — If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do this is with a link to this web page: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Copyright © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation www.coreknowledge.org All Rights Reserved. Core Knowledge Language Arts, Listening & Learning, and Tell It Again! are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and are the property of their respective owners. -

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter Rörande Uppsala Universitet B

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter rörande Uppsala universitet B. INBJUDNINGAR, 189 Redaktör: Per Ström Bild- och uppsatsredaktion: Carl Frängsmyr Layout: Grafisk service Vinjetter: Tryggve Nevéus Omslagsbild: Carl Wilhelmsons inspektorsporträtt av Arvid G. Högbom, Norrlands nation. Jämför sidan 16. Fotograf: Mikael Wallerstedt.. ISSN 0566-3091 ISBN 978-91-513-0525-7 Sättning: Grafisk service, Uppsala universitet Tr yck: DanagårdLiTHO AB, Ödeshög 2019 Kontakt med redaktionen Förfrågningar kring distribution och abonnemang, till exempel rörande levererad upplagas storlek eller önskemål om erhållande av seriens skrifter, riktas till redaktionen under följande e-postadress: [email protected] Promotionsfesten i Uppsala den 25 januari 2019 Innehåll Om Arvid G. Högboms Självbiografiska anteckningar. Av Carl Frängsmyr 7 Självbiografiska anteckningar. AvArvid G. Högbom 15 Personförteckning 73 Program 81 Processionsordning 82 Promotionsarrangemang 83 Rektors hälsningsord 85 Universitetets och fakulteternas inbjudan 87 Promotorernas presentationer Teologiska fakulteten, av Mattias Martinson 89 Juridiska fakulteten, av Minna Gräns 91 Medicinska fakulteten, av Anna Rask-Andersen 93 Farmaceutiska fakulteten, av Per Andrén 95 Historisk-filosofiska fakulteten, avErik Carlson 97 Språkvetenskapliga fakulteten, av Mats Eskhult 99 Samhällsvetenskapliga fakulteten, av Lars Magnusson 101 Utbildningsvetenskapliga fakulteten, av Ann-Carita Evaldsson 103 Teknisk-naturvetenskapliga fakulteten, av Gunilla Kreiss 105 Kortfattat promotionslexikon -

A Pioneer in Quaternary Geology in Scandinavia

doi:10.5200/baltica.2012.25.01 BALTICA Volume 25 Number 1 June 2012 : 1–22 Gerard De Geer – a pioneer in Quaternary geology in Scandinavia Ingemar Cato, Rodney L. Stevens Cato, I., Stevens, R. L., 2011. Gerard De Geer – a pioneer in Quaternary geology in Scandinavia. Baltica 5 (1), 1–22. Vilnius. ISSN 0067–3064. Abstract The paper presents a pioneer in Quaternary geology, both internationally and in Scandinavia – the Swedish geologist and professor Gerard De Geer (1858–1943). This is done, first by highlighting one of his most important contributions to science – the varve chronology – a method he used to describe the Weichselian land–ice recession over Scandinavia, and secondly by the re–publication of a summary article on Gerard De Geer’s early scientific achievement in 1881–1906 related to the Baltic Sea geology, written by his wife, Ebba Hult De Geer. Keywords Gerard De Geer• Clay varves • Varve chronology • Glacial and Postglacial• Quaternary geology • Baltic Sea Ingemar Cato [[email protected]], Geological Survey of Sweden, PO Box 670, SE-751 28 Uppsala, and University of Gothenburg, Department of Earth Sciences, PO Box 460, SE-405 30 Göteborg, Sweden; Rodney Stevens [stevens@gvc. gu.se], University of Gothenburg, Department of Earth Sciences, PO Box 460, SE-405 30 Göteborg, Sweden. Manuscript submitted 11 November 2011. INTRODUCTION It is unfortunately becoming more common in scientific papers that authors do not cite original sources of the methodology, observations and interpretations that their studies are based on. In many cases, the references are to very recent articles dealing with similar issues, which at best have correct references to the original sources. -

Baron Gerard De Geer, For. Mem. RS

No. 3851, AUGUST 21, 1943 NATURE 209 writing in general. He describes four stages, the first three of which he calls mnemonic, pictorial, and OBITUARIES ideographic, while by the fourth the alphabetic is clearly intended. But he is not justified in describing Baron Gerard de Geer, For.Mem.R.S. them as successive evolutionary stages. The first BARON GERARD JACOB DE GEER, whose death two may no doubt be regarded as ·both contributing occurred on July 24, was born in Stockholm on to the invention of writing, but there is no evolu October 2, 1858. Professor of geology at the Univer tionary series here. The alphabet, again, for all true sity of Stockholin from 1897 until 1924, he ended alphabets seem to have a single souree, though it his days as founder-director of the University's a pictographic origin, does not by any means evolve Geochronological Institute. There is more than one from arl. ideographic form of writing. On the contrary, Baron de Geer in Europe. The originator of the though the Japanese in adopting the Chinese script branch of the family from which the famous geologist may tend to give some of its ideograms a purely arose went to Sweden from what is now Belgium at alphabetic value, Chinese, which is ideographic, has the request of King Gustavus Adolphus early in the no alphabet. The nature of the Mohenjodaro script seventeenth century, and there started a large iron is still undetermined, and it is probably impossible and steel industry. In after years successive de Geers to say whet4er it is pictographic or ideographic. -

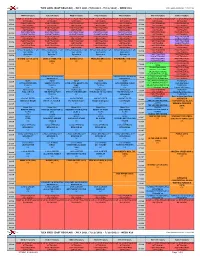

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - JULY 2021 (7/5/2021 - 7/11/2021) - WEEK #28 Date Updated:6/25/2021 11:36:51 AM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - JULY 2021 (7/5/2021 - 7/11/2021) - WEEK #28 Date Updated:6/25/2021 11:36:51 AM MON (7/5/2021) TUE (7/6/2021) WED (7/7/2021) THU (7/8/2021) FRI (7/9/2021) SAT (7/10/2021) SUN (7/11/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) RIPLEY'S BELIEVE IT OR RIPLEY'S BELIEVE IT OR -

Varves in Lake Sediments E a Review

Quaternary Science Reviews 117 (2015) 1e41 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev Invited review Varves in lake sediments e a review * Bernd Zolitschka a, , Pierre Francus b, c, Antti E.K. Ojala d, Arndt Schimmelmann e a Geomorphology and Polar Research (GEOPOLAR), Institute of Geography, University of Bremen, Celsiusstraße FVG-M, D-28359 Bremen, Germany b Centre Eau Terre Environnement, Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique, Quebec-City, Quebec G1K 9A9, Canada c GEOTOP Research Center, Montreal, Quebec H3C 3P8, Canada d Geological Survey of Finland, FI-02151 Espoo, Finland e Indiana University, Department of Geological Sciences, 1001 East 10th Street, Bloomington, IN 47405-1405, USA article info abstract Article history: Downcore counting of laminations in varved sediments offers a direct and incremental dating technique Received 13 August 2014 for high-resolution climatic and environmental archives with at least annual and sometimes even sea- Received in revised form sonal resolution. The pioneering definition of varves by De Geer (1912) had been restricted to rhyth- 20 March 2015 mically deposited proglacial clays. One century later the meaning of ‘varve’ has been expanded to include Accepted 22 March 2015 all annually deposited laminae in terrestrial and marine settings. Under favourable basin configurations Available online 11 April 2015 and environmental conditions, limnic varves are formed due to seasonality of depositional processes from the lake's water column and/or transport from the catchment area. Subsequent to deposition of Keywords: Varve topmost laminae, the physical preservation of the accumulating varved sequence requires the sustained Varve formation absence of sediment mixing, for example via wave action or macrobenthic bioturbation.