The Brothers Grimm and the Yearning for Home Maureen Clack University of Wollongong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mothers Grimm Kindle

MOTHERS GRIMM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Danielle Wood | 224 pages | 01 Oct 2016 | Allen & Unwin | 9781741756746 | English | St Leonards, Australia Mothers Grimm PDF Book Showing An aquatic reptilian-like creature that is an exceptional swimmer. They have a temper that they control and release to become effective killers, particularly when a matter involves a family member or loved one. She took Nick to Weston's car and told Nick that he knew Adalind was upstairs with Renard, and the two guys Weston sent around back knew too. When Wu asks how she got over thinking it was real, she tells him that it didn't matter whether it was real, what mattered was losing her fear of it. Dick Award Nominee I found the characters appealing, and the plot intriguing. This wesen is portrayed as the mythological basis for the Three Little Pigs. The tales are very dark, and while the central theme is motherhood, the stories are truly about womanhood, and society's unrealistic and unfair expectations of all of us. Paperback , pages. The series presents them as the mythological basis for The Story of the Three Bears. In a phone call, his parents called him Monroe, seeming to indicate that it is his first name. The first edition contained 86 stories, and by the seventh edition in , had unique fairy tales. Danielle is currently teaching creative writing at the University of Tasmania. The kiss of a musai secretes a psychotropic substance that causes obsessive infatuation. View all 3 comments. He asks Sean Renard, a police captain, to endorse him so he would be elected for the mayor position. -

Introduction: Fairy Tale Films, Old Tales with a New Spin

Notes Introduction: Fairy Tale Films, Old Tales with a New Spin 1. In terms of terminology, ‘folk tales’ are the orally distributed narratives disseminated in ‘premodern’ times, and ‘fairy tales’ their literary equiva- lent, which often utilise related themes, albeit frequently altered. The term ‘ wonder tale’ was favoured by Vladimir Propp and used to encompass both forms. The general absence of any fairies has created something of a mis- nomer yet ‘fairy tale’ is so commonly used it is unlikely to be replaced. An element of magic is often involved, although not guaranteed, particularly in many cinematic treatments, as we shall see. 2. Each show explores fairy tale features from a contemporary perspective. In Grimm a modern-day detective attempts to solve crimes based on tales from the brothers Grimm (initially) while additionally exploring his mythical ancestry. Once Upon a Time follows another detective (a female bounty hunter in this case) who takes up residence in Storybrooke, a town populated with fairy tale characters and ruled by an evil Queen called Regina. The heroine seeks to reclaim her son from Regina and break the curse that prevents resi- dents realising who they truly are. Sleepy Hollow pushes the detective prem- ise to an absurd limit in resurrecting Ichabod Crane and having him work alongside a modern-day detective investigating cult activity in the area. (Its creators, Roberto Orci and Alex Kurtzman, made a name for themselves with Hercules – which treats mythical figures with similar irreverence – and also worked on Lost, which the series references). Beauty and the Beast is based on another cult series (Ron Koslow’s 1980s CBS series of the same name) in which a male/female duo work together to solve crimes, combining procedural fea- tures with mythical elements. -

Radiogenic Age and Isotopic Studies: Report 3

GSCAN-P—89-2 CA9200982 GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF CANADA PAPER 89-2 RADIOGENIC AGE AND ISOTOPIC STUDIES: REPORT 3 1990 Entity, Mtnat and Cnargi*, Mint* M n**ouroaa Canada ftoaioweat Canada CanadS '•if S ( >* >f->( f STAFF, GEOCHRONOLOGY SECTION: GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF CANADA Research Scientists: Otto van Breemen J. Chris Roddick Randall R. Parrish James K. Mortensen Post-Doctoral Fellows: Francis 6. Dudas Hrnst Hegncr Visiting Scientist: Mary Lou Bevier Professional Scientists: W. Dale L<neridj:e Robert W. Sullivan Patricia A. Hunt Reginald J. Theriaul! Jack L. Macrae Technical Staff: Klaus Suntowski Jean-Claude Bisson Dianne Bellerive Fred B. Quigg Rejean J.G. Segun Sample crushing and preliminary mineral separation arc done by the Mineralogy Section GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF CANADA PAPER 89-2 RADIOGENIC AGE AND ISOTOPIC STUDIES: REPORT 3 1990 ° Minister of Supply and Services Canada 1990 Available in Canada through authorized bookstore agents and other bookstores or by mail from Canadian Government Publishing Centre Supply and Services Canada Ottawa, Canada Kl A 0S9 and from Geological Survey of Canada offices: 601 Booth Street Ottawa, Canada Kl A 0E8 3303-33rd Street N.W., Calgary, Alberta T2L2A7 100 West Pender Street Vancouver, B.C. V6B 1R8 A deposit copy of this publication is also available for reference in public libraries across Canada Cat. No. M44-89/2E ISBN 0-660-13699-6 Price subject to change without notice Cover Description: Aerial photograph of the New Quebec Crater, a meteorite impact structure in northern Ungava Peninsula, Quebec, taken in 1985 by P.B. Robertson (GSC 204955 B-l). The diameter of the lake is about 3.4km and the view is towards the east-southeast. -

Implications for Gale Crater's Geochemistry

First detection of fluorine on Mars: Implications for Gale Crater’s geochemistry Olivier Forni, Michael Gaft, Michael Toplis, Samuel Clegg, Sylvestre Maurice, Roger Wiens, Nicolas Mangold, Olivier Gasnault, Violaine Sautter, Stéphane Le Mouélic, et al. To cite this version: Olivier Forni, Michael Gaft, Michael Toplis, Samuel Clegg, Sylvestre Maurice, et al.. First detection of fluorine on Mars: Implications for Gale Crater’s geochemistry. Geophysical Research Letters, American Geophysical Union, 2015, 42 (4), pp.1020-1028. 10.1002/2014GL062742. hal-02373397 HAL Id: hal-02373397 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02373397 Submitted on 8 Jul 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright PUBLICATIONS Geophysical Research Letters RESEARCH LETTER First detection of fluorine on Mars: Implications 10.1002/2014GL062742 for Gale Crater’s geochemistry Key Points: Olivier Forni1,2, Michael Gaft3, Michael J. Toplis1,2, Samuel M. Clegg4, Sylvestre Maurice1,2, • fl First detection of uorine at the 4 5 1,2 6 5 Martian surface Roger C. Wiens , Nicolas Mangold , Olivier Gasnault , Violaine Sautter , Stéphane Le Mouélic , 1,2 5 4 7 4 • High sensitivity of fluorine detection Pierre-Yves Meslin , Marion Nachon , Rhonda E. -

Naturalism, the New Journalism, and the Tradition of the Modern American Fact-Based Homicide Novel

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. U·M·I University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml48106-1346 USA 3131761-4700 800!521-0600 Order Number 9406702 Naturalism, the new journalism, and the tradition of the modern American fact-based homicide novel Whited, Lana Ann, Ph.D. -

Mars Science Laboratory NAC Technology and Innovation Committee Nov

Mars Science Laboratory NAC Technology And Innovation Committee Nov. 15, 2012 Dave Lavery Program Executive Mars Science Laboratory 1 Mars Science Laboratory / Curiosity • Mission Context • Spacecraft / Rover Overview • Entry, Descent and Landing (EDL) • Early Surface Operations • Critical Technologies • Effective Outreach Mars Exploration Program An Integrated, Strategic Program 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2016 & Beyond MRO Mars Express Mars future Collaboration planning Odyssey MAVEN underway! MSL/Curiosity Spirit & Phoenix Opportunity (completed) 3 Pathfinder MER MSL Rover Family Portrait Rover Mass 10.5 kg 174 kg 950 kg Driving Distance 600m / (req’t/actual) 10m/102m 35,345m 20,000m/TBD Mission Duration 10 sols/ 90 sols/ (req’t/actual) 83 sols 3,132 sols 687 sols/TBD Power / Sol 130 w/hr 499-950 w/hr ~2500 w/hr Instruments / Mass 1 / <1.5 kg 7 / 5.5 kg 10 / 75 kg Data Return 2.9 Mb/sol 50-150 Mb/sol 100-400 Mb/sol EDL Ballistic Entry Ballistic Entry Guided Entry Science Goals MSL’s primary scientific goal is to explore a landing site as a potential habitat for life, and assess its potential for preservation of biosignatures Objectives include: Assessing the biological potential of the site by investigating organic compounds, other relevant elements, and biomarkers Characterizing geology and geochemistry, including chemical, mineralogical, and isotopic composition, and geological processes Investigating the role of water, atmospheric evolution, and modern weather/climate Characterizing the spectrum of surface radiation MSL Science Payload REMOTE SENSING ChemCam Mastcam Mastcam (M. Malin, MSSS) - Color and telephoto imaging, video, atmospheric opacity RAD ChemCam (R. -

The Tales of the Grimm Brothers in Colombia: Introduction, Dissemination, and Reception

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2012 The alest of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception Alexandra Michaelis-Vultorius Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Michaelis-Vultorius, Alexandra, "The alet s of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception" (2012). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 386. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE TALES OF THE GRIMM BROTHERS IN COLOMBIA: INTRODUCTION, DISSEMINATION, AND RECEPTION by ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: MODERN LANGUAGES (German Studies) Approved by: __________________________________ Advisor Date __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS 2011 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my parents, Lucio and Clemencia, for your unconditional love and support, for instilling in me the joy of learning, and for believing in happy endings. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This journey with the Brothers Grimm was made possible through the valuable help, expertise, and kindness of a great number of people. First and foremost I want to thank my advisor and mentor, Professor Don Haase. You have been a wonderful teacher and a great inspiration for me over the past years. I am deeply grateful for your insight, guidance, dedication, and infinite patience throughout the writing of this dissertation. -

Majors Creek Quarterly Notes

Quarterly Notes Geological Survey of New South Wales August 2014 No 141 New geochronological and isotopic constraints on granitoid-related gold mineralisation near Majors Creek, New South Wales Abstract Previous workers have variously interpreted the style of gold mineralisation in the Majors Creek area, southeastern New South Wales, as epithermal or granitoid-related. The epithermal model implies that the mineralising event occurred during the opening of the Eden–Comerong–Yalwal rift zone, several million years after assembly of the host Braidwood Granodiorite. We present new 40Ar/39Ar dating of white micas intimately associated with gold-bearing sulfides. These analyses give an age of 410.9 ± 2.0 Ma (2σ) for the gold-bearing greisen at Dargues Reef and 410.8 ± 1.8 Ma (2σ) for vein-style gold mineralisation at the Great Star mine (Majors Creek). These ages lie within the error of previous U–Pb SHRIMP ages for the Braidwood Granodiorite, which strongly suggests that a single hydrothermal mineralising event occurred in the Majors Creek district. Sulfur isotope data supports the interpretation that open-system 34S–32S fluid–mineral fractionation occurred during the mineralising event at Dargues Reef. By contrast, the data for base metal bearing veins at Majors Creek indicates that closed-system 34S–32S fluid–mineral fractionation was predominant. A genetic model is proposed for mineralisation in the Majors Creek district. The mineralogy, intrusive relationships and physiography at Dargues Reef and other key vein systems in the area suggest that magmatic-dominated hydrothermal fluids exsolved from late-stage felsic phases of the Braidwood Granodiorite. These mineralising fluids were then focused into fractures and along pre-mineralisation mafic- to intermediate dykes, which may also have been the focus of post-mineralisation intrusive phases. -

Classification of Animals

Grade 3 Core Knowledge Language Arts® • Listening & Learning™ Strand Classification of Animals of Classification Tell It Again!™ Read-Aloud Anthology Read-Aloud Again!™ It Tell Classification of Animals Tell It Again!™ Read-Aloud Anthology Listening & Learning™ Strand GrAde 3 Core Knowledge Language Arts® Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. You are free: to Share — to copy, distribute and transmit the work to Remix — to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution — You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike — If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do this is with a link to this web page: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Copyright © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation www.coreknowledge.org All Rights Reserved. Core Knowledge Language Arts, Listening & Learning, and Tell It Again! are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and are the property of their respective owners. -

Free Astronomy Magazine March-April 2021

cover EN.qxp_l'astrofilo 25/02/2021 16:35 Page 1 THE FREE MULTIMEDIA MAGAZINE THAT KEEPS YOU UPDATED ON WHAT IS HAPPENING IN SPACE Bi-monthly magazine of scientific and technical information ✶ March-April 2021 S P E C I A L I S S U E Mars Rovers from Sojourner to Perseverance www.astropublishing.com ✶✶www.facebook.com/astropublishing [email protected] colophon EN_l'astrofilo 25/02/2021 16:33 Page 2 www.northek.it www.facebook.com/northek.it [email protected] phone +39 01599521 Ritchey-Chrétien ➤ SCHOTT Supremax 33 optics ➤ optical diameter 355 mm ➤ useful diameter 350 mm ➤ focal length 2800 mm Dall-Kirkham ➤ focal ratio f/8 ➤ SCHOTT Supremax 33 optics ➤ 18-point floating cell ➤ optical diameter 355 mm ➤ customized focuser ➤ useful diameter 350 mm ➤ focal length 7000 mm ➤ focal ratio f/20 Cassegrain ➤ 18-point floating cell ➤ SCHOTT Supremax 33 optics ➤ Feather Touch 2.5” focuser ➤ optical diameter 355 mm ➤ useful diameter 350 mm ➤ focal length 5250 mm ➤ focal ratio f/15 ➤ 18-point floating cell ➤ Feather Touch 2.5” focuser colophon EN_l'astrofilo 25/02/2021 16:33 Page 3 Mars Rovers BI-MONTHLY MAGAZINE OF SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION 4 from Sojourner to Perseverance FREELY AVAILABLE THROUGH THE INTERNET March-April 2021 Sojourner 6 Spirit & Opportunity English edition of the magazine lA’ STROFILO 14 Editor in chief Michele Ferrara Scientific advisor Prof. Enrico Maria Corsini Publisher Astro Publishing di Pirlo L. Via Bonomelli, 106 25049 Iseo - BS - ITALY Curiosity email [email protected] Internet Service Provider Aruba S.p.A. Via San Clemente, 53 24036 Ponte San Pietro - BG - ITALY 26 Copyright All material in this magazine is, unless otherwise stated, property of Astro Publishing di Pirlo L. -

ASX Announcement March 2014

ASX Announcement March 2014 GUNDAROO GOLD PROJECT General Manager 5th March 2014 The Company Announcements Office Australian Securities Exchange Electronic Lodgement System Dear Sir/Madam CENTREX COMPLETES MAJOR GEOCHEMICAL PROGRAM FOR GOLD PROJECT IN NSW Highlights 245 stream sediment sample points collected over southern half of Gundaroo Gold Project 9 anomalous gold target areas identified for further evaluation Geological setting favourable for intrusion-related gold deposits Detailed mapping and shallow drilling will further prioritise targets Summary Centrex Metals Limited (“Centrex”) has completed a major stream sediment geochemical program over the southern half of its Gundaroo Gold Project in NSW. A total of 245 stream sediment sample points were taken and analysed for both path finder elements and gold. Centrex planned this program around a high-resolution magnetic and radiometric survey it completed in October 2013. The Company is targeting intrusion-related gold deposits surrounding a large granodiorite intrusion and its associated contact metamorphic halo within a host turbidite and black shale sequence. The project lies within a regional scale fault zone, with 11 historic gold workings identified in the area during the field investigations. The assay results have identified 9 target areas of gold anomalism for further evaluation. Detailed mapping and shallow drilling will be used to further prioritise the targets. ASX Announcement — March 2014 Gundaroo Gold Project The Gundaroo Gold Project encompasses a 281km2 exploration licence (EL8133) located 18km east of Yass within the East Lachlan Fold Belt in NSW. The project is located roughly 10km due west of Centrex’s existing Goulburn Zinc-Lead Joint Venture with Shandong 5th Geo-Mineral Prospecting Institute (“Shandong”). -

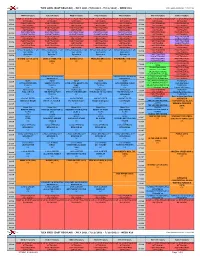

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - JULY 2021 (7/5/2021 - 7/11/2021) - WEEK #28 Date Updated:6/25/2021 11:36:51 AM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - JULY 2021 (7/5/2021 - 7/11/2021) - WEEK #28 Date Updated:6/25/2021 11:36:51 AM MON (7/5/2021) TUE (7/6/2021) WED (7/7/2021) THU (7/8/2021) FRI (7/9/2021) SAT (7/10/2021) SUN (7/11/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) RIPLEY'S BELIEVE IT OR RIPLEY'S BELIEVE IT OR