Sailing with the CHARLES W. MORGAN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rigging Guide Viola 14 Lug Rig

Rigging Guide Viola 14 Lug Rig The Balanced Lug Rig The balanced lug rig is often chosen by small boat designers for having the following favourable characteristics: Traditional in appearance Cheap to rig Easy home construction of the spars involved Relatively short spars for a given sail area Powerful sail that is easy to control for the sail being self-vanging Very quickly to raise and to strike the sail (important for sail & oar use as well as emergencies). Good sail shape, also when reefed The lug rig is a very good choice for the Viola canoe if looking for a versatile rig that can easily be reefed, also on the water. It is excellent for touring or camp-sailing. The picture below shows the definitions used throughout this document for the various parts of a balanced lug rig. Making the Mast Mast sections are to be made of 6000 series T6 series aluminium tubes. The instructions for making the shoulder and bearings on the top mast section by using glass tape epoxied to the mast and a short section of aluminium tube of the same diameter as the bottom mast section for the shoulder (to ensure that the top mast section sits well in the bottom section) can be found in the Viola 14 plans. Dimensions/details bottom mast section: Length 2450mm Outside diameter 60mm Inside diameter 56mm (2mm wall thickness) Centre halyard cleat 550mm from the bottom of the mast. Bolt or rivet the halyard cleat to the mast. Optional saddle just above mast partner level for the dagger board elastic. -

Build the USS CONSTITUTION the World’S Oldest Commissioned Naval Vessel Afloat 12 Build the USS CONSTITUTION Contents STAGE PAGE 111 Sails 245

Build the USS CONSTITUTION The world’s oldest commissioned naval vessel afloat 12 Build the USS CONSTITUTION Contents STAGE PAGE 111 Sails 245 112 Sails and flags 247 113 Sails 249 114 Sails 251 115 Sails 253 116 Sails 255 117 Sails 257 118 Sails 259 119 Sails 261 120 Sails 263 Editorial and design by Continuo Creative, 39-41 North Road, London N7 9DP. Published in the UK by De Agostini UK Ltd, Battersea Studios 2, 82 Silverthorne Road, London SW8 3HE. Published in the USA by De Agostini Publishing USA, Inc.,121 E. Calhoun Street, Woodstock, IL 60098. All rights reserved © 2017 Warning: Not suitable for children under the age of 14. This product is not a toy and is not designed or intended for use in play. Items may vary from those shown. USS CONSTITUTION STAGE: 111 C 79 Sails 75 68 V3. Fore topmast staysail V4. Main topmast staysail 57 V4 V3 111C Following the plan, attach the four yards (57, 68, 75 and 79) to the front of the foremast. 111D Now prepare the three sections of the mainmast, following the plan. The mainmast (81) with fittings and top, the main topmast (106) and the main topgallant mast (112) following the same process as with the foremast. 111A Retrieve the spritsail A D yard (20) and secure it to the 81 bowsprit with the parrel (23). Tie the parrel to the yard, then pass it over the bowsprit and secure the free end to the yard. 20 112 106 B E 64 111B Retrieve the foremast yards (57, 68, 75 and 79) prepared in Stage 110 and paint them with wood stain. -

ILLUSTRATED CATALOG and Price List No

ILLUSTRATED CATALOG and Price List No. 43 A. J. FISHER, INC. 1 002 Etowah Avenue ROYAL OAK, MICHIGAN 48067 Phone: Lincoln 1-0352 R.L. lrwin- Proprietor ~SE oMp~ oplend;d ea<h whh he< g.ace, he< glo•y, Her memory of old song or comrade's story, Still in my mind the image of life's need, Beauty in hardest action, beauty indeed. "They built great ships and sailed them" sounds most brave Whatever arts we have or fail to have; I touch my country's mind, I come to grips With half her purpose, thinking of these ships, That art untouched by softness, all that line Drawn ringing hard to stand the test of brine, That nobleness and grandeur, all that beauty Born of a manly life and bitter duty, That splendour of fine bows which yet could stand The shock of rollers never checked by land. That art of masts, sail crowded, fit to break, Yet stayed to strength and backstayed into rake, The life demanded by that art, the keen Eye-puckered, hard-case seamen, silent, lean They are grander things than all the art of towns, Their tests are tempests and the sea that drowns, .· They are my country's line, her great art done By strong brains labouring on the thought unwon, . ;, They mark our passage as a race of men, Earth will not see such ships as those again. -John Masefield .. To you craftsmen Clipper Ship -- "Young America" Whaling Bark - - "Wanderer" who love ships .. ~ HERE'S a world of satisfaction in '--U creating accurate replicas of old and new ships clippers and yachts, corsairs and galleons, frigates and destroyers. -

Rigging Guide

Liberty Rigging Guide Manufactured by Hansa Sailing Systems Pty Ltd ABN 56 079 318 031 Head Office: 4/4 Cumberland Avenue SOUTH NOWRA NSW 2541 AUSTRALIA Postal: PO Box 5048 NOWRA DC NSW 2541 Telephone: +61 2 4403 0595 Facsimile: +61 2 4403 0598 Email: [email protected] Website: www.hansasailing.com 1 Index Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 Description of Craft: The Liberty Specification ……………………………………………………………………………………………………...5 General ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………6 Maintenance & Repairs ………………………………………………………………………………………….7 Safety Recommendations …………………………………………………………………………….………...8 PART ONE Special Features of the Liberty ……………………………………………………………………………..….9 PART TWO How to Rig a Liberty Stepping the Mast, fitting the boom ………………………………………………………………………….12 Stepping the Foremast …………………………………………………………………………………………14 Setting up Main and Jib Sheets ……………………………………………………………………………….15 Reefing the Main ………………………………………………………………………………………………..16 Reefing and Furling the Jib …………………………………………………………………………………….17 Steering …………………………………………………………………………………………………………..18 Launching ………………………………………………………………………………………………………..19 PART THREE Liberty Servo Assist System—Overview ……………………………………………………………………..19 Control Box ………………………………………………………………………………………………………20 The Batteries …………………………………………………………………………………………………….21 The Helm Winch ………………………………………………………………………………………………...21 The Mainsheet Winch …………………………………………………………………………………………..22 The Jibsheet Winch ……………………………………………………………………………………………..22 Controllers ………………………………………………………………………………………………………..23 -

Setting up Shrouds with Deadeyes and Lanyards

ADVISORY BOARD Mr Greg Adams Adcast Consolidated Pty Ltd Mr Alan Hurst Yaringa Boat Sales Mr Peter Tardrew Quarterdeck Marine Pty Ltd Mr Tom Whitfield T&C Whitfield Boatbuilders WOODEN BOAT FITTINGS 43 FINCHAM CRESCENT WANNIASSA, ACT 2903, AUSTRALIA TEL: +61 2 6296 1409 EMAIL: [email protected] WEB: www.woodenboatfittings.com SETTING UP SHROUDS WITH DEADEYES AND LANYARDS ——————————————————-- HOW TO RIG DEADEYES & LANYARDS ——————————————————-- Extracted from Hervey Garrett Smith, “The Arts of the Sailor” ============================================= Although this ancient art of the rigger is considered obsolete by many present-day yachtsmen, such is far from true, for deadeyes and lanyards are still being used in all manner of sailing craft, being particularly appropriate in the traditional types-such as the Friendship sloops, the Chesapeake bugeyes, or the skipjacks. While their salty, old-fashioned appearance may have been the factor that has induced more than one sentimental yachtsman to adopt them, from the standpoint of practicability they have sufficient merit in their own right to justify their use in any craft of a suitable type. There are two reasons why I feel some discussion of this uncommon art is in order: in the first place, specific, authentic information on the subject is not within easy reach of everyone, and secondly, there is a great deal of misunderstanding as to their practical application in the modern yacht. The principal advantage gained by setting up standing rigging with lanyards is elasticity. This is particularly desirable in yachts that are broad of beam, having high initial stability, and heavily sparred. The resiliency of such a rig makes a yacht easy on her gear, for spars and rigging can flex and give with every sudden strain. -

The Cap Rail... Bulwark Details

bowsprit notch The Cap Rail... It also hangs over the bulwarks slightly inboard and out- board. Draw a second line 1/8” inside the traced outline to The cap rail is also quite easy to make and install. But establish the cap rail width. Use a sharp blade to cut out before you begin, carve the slot that will accept the the cap rail in one piece. Don’t cut along your lines bowsprit. The cap rail is actually placed over the bowsprit exactly. In fact, cut about 1/16” outside of these lines to which will be seated in this notch cut out of the bulwarks. create a ‘much oversized version of the cap rail’. After glu- (photo inset) The bowsprit will be made from 1/8” square ing it to the top of the bulwarks and stanchions, you can stock. Therefore, the notch at the bow should be cut to use some sandpaper to narrow the cap rail to its actual 1/8” wide and just as deep (maybe a little deeper and width. Keep the over hang inboard and outboard consis- angled). The slot must be big enough to allow the bowsprit tent while sanding. The plans also indicate that the cap to slide into it after the cap rail is fixed in place. Check out rail should be painted dark brown. I decided not to use the close-up drawing of this area on one of the blue prints. paint and stained the cap rail instead. I chose a shade Once you are satisfied that the bowsprit will easily slide into that was not to dark but sill created a pleasing contrast place, start building the cap rail. -

Chapter Eighteen Standing Rigging There Are Many Methods and Techniques Which Can Be Strops with a 3.5 Mm Deadeye and 8 with a 2.5 Mm Dead- Used to Rig a Ship Model

Eyebolt Deadeye link Deadeye strop strop 3.5 mm 2.5 mm Middle link Toe link Preventer link Chapter Eighteen Standing Rigging There are many methods and techniques which can be strops with a 3.5 mm deadeye and 8 with a 2.5 mm dead- used to rig a ship model. One method is described here. eye. Make them all at this time. Be sure to examine the plans carefully for all of the rigging Step 3 — Glue a deadeye into the strop as shown. Be details. The order in which the descriptions are written careful while positioning the deadeye so the holes are below is the same order used to rig the prototype model. aligned properly. All of the sizes for each rigging line are noted and they Step 4 — Bend the loose ends of the wire around the appear on the plans as well. To prepare for rigging the deadeye. shrouds you must first create the chain plate assemblies. Step 5 — Trim off the excess wire. You can apply a drop These assemblies are used to secure the shrouds with of glue to the top of the deadeye to permanently secure deadeyes and lanyards along the channels. All of the the wire in the groove. chain plate elements will be made using 28 gauge black wire. Each element can be made with the aid of a simple Eye bolt links (8 needed) — create a new jig with two jig. The jig is made by inserting small nails or pins into nails. The pins should be spaced 7/32” apart. -

Catalog71 Update 6-6-21

To you craftsmen who love ships . here’s a world of satisfaction in creating accurate replicas of old and new ships_– clippers, yachts, frigates, tugs and freighters. You who are about to undertake your first model, as well as you who have been building for years, will find something herein that will interest you. Our sincere wish is that through this catalog we may be of real help to you in creating your models– and that this will be the beginning of a riendship that will long endure. About A. J. Fisher A. J. Fisher was founded in 1925 by Archibald J. Fisher. Archibald was a seaman who plied the Oceans and Great Lakes as a chief engineer. Mr. Fisher ran the business until he passed away in 1957. Raymond Irwin bought the business at that time and in 1960 Robert Irwin, his son, joined him when he left the service. Robert took over A. J. Fisher when his father retired in 1974. Robert continued A. J. Fisher until 2001 when he retired. A. J. Fisher has been owned by William Partridge since 2003. Our goal is to maintain the fine quality ship model kits produced for over 90 years and to update and reissue over 20 of the original A.J. Fisher classic solid hull ship model kits. The A. J. Fisher fittings listed in this catalog are cast in pewter unless otherwise noted. Whether you are about to begin your first model or if you have been building models for years we hope there is something in the A. -

H.M.S Victory 1805

H.M.S VICTORY 1805 Exact scale model of the 100-Gun British Ship of the Line. This, the fifth ship of the Royal Navy to bear the name Victory, had three major battle honours. The first being the Battle of Ushant 1781, the second, the Battle of St. Vincent 1797 and the third, for which she is most famed, the Battle of Trafalgar 1805. By the end of the Battle of Trafalgar, there was not a mast, spar, shroud or sail on board Victory that had not been severely damaged, lost or destroyed in the conflict. Manual 2 of 3 Masting & Rigging Additional photos of every stage of construction can be found on our website at: http://www.jotika-ltd.com Nelsons Navy Kits manufactured and distributed by JoTiKa Ltd. Model Marine Warehouse, Hadzor, Droitwich, WR9 7DS. Tel ~ +44 (0) 1905 776 073 Fax ~ +44 (0) 1905 776 712 Email ~ [email protected] Masts & Bowsprit You may find it easier to avoid turning the round dowel into an oval dowel when tapering by using a David plane, draw knife or similar as follows: 1. Slice the dowel (running with the grain), from a round at the start point of the taper to a square at the end of the taper. 2. Repeat this process so that the dowel runs from round at the start of the taper to an eight sided polygon at the end of the taper. 3. Repeat step two as desired so that the dowel runs from a round at the start of the taper to a 16 or 32 sided polygon at the end, of a diameter marginally more than that required. -

Sailing Parts & Accessories

SAILING PARTS & ACCESSORIES SAILING PARTS & ACCESSORIES CONTENTS ITEM PAGE LIFE VESTS / PFD 2-3 PET PFD / WET WEAR / SAFETY 4 TRAPEZE / GLOVES 5 TRAPEZE 6-7 WING SEATS / BACK RESTS 8 SCAN TO GO TO HOBIE SUPPORT PAGES SAILS 9-11 BATTENS / SAIL ACCESSORIES 12-13 WIND INDICATORS 14 TRAMPOLINES 15 RIGHTING 16-17 STEERING / RUDDERS / TILLERS 18-19 SAIL TRIMMING / HARDWARE 20-25 LINE 26 HATCHES / BAGS 27 SCAN TO GO TO HOBIE PARTS LOOKUP TRAILERS, STORAGE 28 TRAILER ACCESSORIES / MAST STEPPING 29 BEACH WHEELS / CARTS 30 COVERS / BAGS 30-31 STICKERS / TOOLS / REPAIRS / MAINTENANCE 32-33 MISC. ACCESSORIES / HOBIE BOOK 34-35 HOBIE SUNGLASSES 36-39 APPAREL / HATS / ACCESSORIES 40-41 Note: Freight to dealers is not included in pricing. No portion of this catalog may be reproduced without the express permission of the Hobie Cat Company. All rights reserved. ©2020 Hobie Cat Company. Oceanside, CA 92056 Pricing subject to change. Printed in USA HOBIE.COM LIFE VESTS / PFD LIFE VESTS & PFDs S6103xx (xx = size) HOBIE THIN-BACK by Stohlquist MEN'S SUN Features a thin foam back design ... perfect for use with Hobie Vantage seats. This thinner back profile provides more mobility and comfort, while reducing interference with taller seat backs. THIN-BACK S6103-6 THIN-BACK FISH S6107 FEATURES: Thin back design works with all seat styles; Graded Sizing provides the best pos- sible fit; Open sides for ventilation; Cross-chest cinch harness for zero ride-up; Mesh shoulders & interior panels for maximum ventilation; Adjustable shoulders, and dual forward pulls for -

Corsair Sailing Manual

SAILING MANUAL 28 24 For All Corsair Models November, 1997 Sailing Manual For All Corsair Models Including F-24, F-28 and F-31 This manual has been compiled to help you to operate your craft with safety and enjoyment. It contains details of the craft, the equipment supplied or fitted, its systems, and information on its operation and maintenance. Please read it carefully and familiarize yourself with the craft before using it. If this is your first craft, or you are changing to a type of craft you are not familiar with, for your own comfort or safety, please ensure that you obtain handling and operating experience before assuming command of the craft. Your dealer or national sailing federation or yacht club will be pleased to advise you of local sailing schools or competent instructors. PLEASE KEEP THIS MANUAL IN A SECURE PLACE, AND PASS ON TO THE NEW OWNER WHEN YOU SELL THE CRAFT Model_____________________ Hull Number__________________________________ Owner 1. ___________________________ Owner 2. ___________________________ Owner 3. __________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ _________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ _________________________________ ___________________________________ __________________________________ _________________________________ Built By: Corsair Marine, Inc. 150 Reed Court, Chula Vista, CA 91911, U.S.A. CORSAIR MARINE, Inc. Page 1 Copyright © 1997 By Corsair Marine Contents General.............................................. -

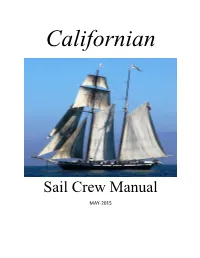

Sail Crew Manual

Californian Sail Crew Manual MAY-2015 Table of Contents Basic Terminology and Structural Description Introduction and Orientation1 The Hull2 Spars2 Basic Rigging2 Standing Rigging3 Running Rigging3 Lines That Control the Yards and Gaffs3 Lines That Control the Sails4 Where is Everything? Sail Plan5 Spars and Yards6 Foredeck Dog Rail7 Starboard Foremast Fife Rail8 Port Foremast Fife Rail9 Starboard Foremast Pin Rail, In Port10 Starboard Foremast Pin Rail, Underway11 Port Foremast Pin Rail, In Port12 Port Foremast Pin Rail, Underway13 Starboard Amidships in Port, Rigged to get Underway14 Port Amidships, In Port15 Starboard Mainmast Pin Rail, In Port16 Starboard Mainmast Pin Rail, Underway17 Port Mainmast Pin Rail, In Port18 Port Mainmast Pin Rail, Underway19 Starboard Mainmast Brace Bench20 Port Mainmast Brace Bench21 Starboard Cockpit22 (ii) Port Cockpit23 Deck Plan Layout24 Prepare the Californian to get Underway Setting up the Deck 25 Muster 26 Captains Briefing 27 Underway Commands Hands to Stations for Getting Underway 28 Hands to Set Sail, Man the Mainsail/Foresail Gear 29 Man the Staysail/Inner/Outer Gear 31 Put the Squares in their Gear 34 Ready About 37 Wear-O 38 Hands to Take Sail – Topsails 39 Man the Inner/Outer/Staysail gear for dousing 40 Man the Foresail/Mainsail gear for dousing 41 Docking 42 Fire Extinguisher Locations aboard Californian 43 Pin Rail Diagram for Californian 44 (iii) Forward The Californian is owned and operated by the Maritime Museum of San Diego. The Museum establishes all safety and crew qualification standards. This guide is intended to give a basic understanding of the ship and actions required of the crew.