Preparing the UK for an All-IP Future: Experiences from Other Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BT Smart Hub: Marketing Claims Substantiation

BT Smart Hub: Marketing claims substantiation July 2016 BT Smart Hub marketing claims substantiation – July 2016 Contents 1.1 Introduction 3 1.2 How is the most powerful wi-fi tested? 4 Routers tested 4 What do we measure? 5 How do we test? 5 Devices used in the test 6 Where were the tests completed? 6 Sagemcom floor plan 6 BT floor plan 7 Live customer homes 7 1.3 Test set-up 8 1.4 Results 9 BT test house 2.4 GHz 9 BT test house 5 GHz 14 Sagemcom test house 2.4 GHz 17 Sagemcom test house 5 GHz 20 10 real homes 21 1.5 Conclusion 23 Appendix 1 - Test home floor plans 24 Appendix 2 - Coverage testing with Interference 34 Appendix 3 - TalkTalk Wi-Fi Hub 37 2 BT Smart Hub marketing claims substantiation – July 2016 1.1 Introduction The BT Smart Hub provides the UK’s most powerful wi-fi signal. The following report presents extensive in-home and lab wi-fi testing of the BT Smart Hub compared to all major UK broadband providers. At any distance from the router, the BT Smart Hub will always provide the most powerful wi-fi signal. The tests were based on the IEEE802.11T method, to • The tests capture speeds for normal user tasks. provide robust and repeatable data, taking into account • Turntables were used to ensure the routers did not previous Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) rulings and exhibit directionality and to ensure a fair test. guidance on wi-fi performance claims: • Hundreds of data-points were captured to ensure • The tests were carried out on 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz to results were repeatable and reliable. -

BT Group Plc Annual Report 2020 BT Group Plc Annual Report 2020 Strategic Report 1

BT Group plc Group BT Annual Report 2020 Beyond Limits BT Group plc Annual Report 2020 BT Group plc Annual Report 2020 Strategic report 1 New BT Halo. ... of new products and services Contents Combining the We launched BT Halo, We’re best of 4G, 5G our best ever converged Strategic report connectivity package. and fibre. ... of flexible TV A message from our Chairman 2 A message from our Chief Executive 4 packages About BT 6 investing Our range of new flexible TV Executive Committee 8 packages aims to disrupt the Customers and markets 10 UK’s pay TV market and keep Regulatory update 12 pace with the rising tide of in the streamers. Our business model 14 Our strategy 16 Strategic progress 18 ... of next generation Our stakeholders 24 future... fibre broadband Culture and colleagues 30 We expect to invest around Introducing the Colleague Board 32 £12bn to connect 20m Section 172 statement 34 premises by mid-to-late-20s Non-financial information statement 35 if the conditions are right. Digital impact and sustainability 36 Our key performance indicators 40 Our performance as a sustainable and responsible business 42 ... of our Group performance 43 A letter from the Chair of Openreach 51 best-in-class How we manage risk 52 network ... to keep us all Our principal risks and uncertainties 53 5G makes a measurable connected Viability statement 64 difference to everyday During the pandemic, experiences and opens we’re helping those who up even more exciting need us the most. Corporate governance report 65 new experiences. Financial statements 117 .. -

Martlesham Heath Area Specific Guidance June 2001

Supplementary Planning Guidance 12.8 Hi-Tech Cluster: Martlesham Heath Area Specific Guidance June 2001 Following the reforms to the Planning system through the enactment of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 all Supplementary Planning Guidance’s can only be kept for a maximum of three years. It is the District Council’s intention to review each Supplementary Planning Guidance in this time and reproduce these publications as Supplementary Planning Documents which will support the policies to be found in the Local Development Framework which is to replace the existing Suffolk Coastal Local Plan First Alteration, February 2001. Some Supplementary Planning Guidance dates back to the early 1990’s and may no longer be appropriate as the site or issue may have been resolved so these documents will be phased out of the production and will not support the Local Development Framework. Those to be kept will be reviewed and republished in accordance with new guidelines for public consultation. A list of those to be kept can be found in the Suffolk Coastal Local Development Scheme December 2004. Please be aware when reading this guidance that some of the Government organisations referred to no longer exist or do so under a different name. For example MAFF (Ministry for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food) is no longer in operation but all responsibilities and duties are now dealt with by DEFRA (Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs). Another example may be the DETR (Department of Environment, Transport and Regions) whose responsibilities are now dealt with in part by the DCLG (Department of Communities & Local Government). -

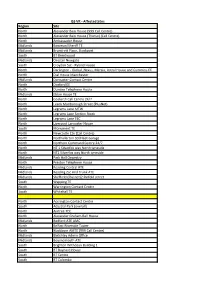

LTB 342.2019 Attachment 1

ISS VR - Affected Sites Region Site North Alexander Bain House (999 Call Centre) North Alexander Bain House (Thurso) (Call Centre) North Ambassador House Midlands Bowman/Sheriff TE Midlands Brundrett Place, Stockport South BT Brentwood Midlands Chester Newgate South Croydon Ssc - Ryland House North Darlington - Global ,Nexus, Mercia, Astral House and Cummins EE North Dial House Manchester Midlands Doncaster Contact Centre North Doxford EE North Dundee Telephone House Midlands Eldon House TE North Gosforth Call Centre 24/7 North Leeds Marlborough Street (PlusNet) North Legrams Lane MTW North Legrams Lane Section Stock North Legrams Lane TEC North Liverpool Lancaster House South Monument TE North Newcastle Cte (Call Centre) North Northallerton SD/Fleet Garage North Northern Command Centre 24/7 North NT 1 Silverfox way North tyneside North NT2 Silverfox way North tyneside Midlands Park Hall Oswestry North Preston Telephone House Midlands Reading Central ATE Midlands Reading Zsc And Trunk ATE Midlands Sheffield (Plusnet)2 Pinfold street South Wapping TE North Warrington Contact Centre South Whitehall TE North Accrington Contact Centre South Adastral Park (overall) North Aintree TEC North Alexander Graham Bell House Midlands Bedford ATE AMC North Belfast Riverside Tower North Blackburn AMTE (999 Call Centre) Midlands Bletchley Admin Office Midlands Bournemouth ATE South Brighton Withdean Building 1 South BT Baynard House South BT Centre South BT Colombo South BT Mill House South BT Tower South Canterbury Becket House South Crawley New TEC -

Inventing the Communications Revolution in Post-War Britain

Information and Control: Inventing the Communications Revolution in Post-War Britain Jacob William Ward UCL PhD History of Science and Technology 1 I, Jacob William Ward, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract This thesis undertakes the first history of the post-war British telephone system, and addresses it through the lens of both actors’ and analysts’ emphases on the importance of ‘information’ and ‘control’. I explore both through a range of chapters on organisational history, laboratories, telephone exchanges, transmission technologies, futurology, transatlantic communications, and privatisation. The ideal of an ‘information network’ or an ‘information age’ is present to varying extents in all these chapters, as are deployments of different forms of control. The most pervasive, and controversial, form of control throughout this history is computer control, but I show that other forms of control, including environmental, spatial, and temporal, are all also important. I make three arguments: first, that the technological characteristics of the telephone system meant that its liberalisation and privatisation were much more ambiguous for competition and monopoly than expected; second, that information has been more important to the telephone system as an ideal to strive for, rather than the telephone system’s contribution to creating an apparent information age; third, that control is a more useful concept than information for analysing the history of the telephone system, but more work is needed to study the discursive significance of ‘control’ itself. 3 Acknowledgements There are many people to whom I owe thanks for making this thesis possible, and here I can only name some of them. -

Land South and East of Adastral Park Suffolk

Land south and east of Adastral Park Suffolk Planning Statement March 2017 Carlyle Land and CEG Land south and east of Adastral Park March 2017 PLANNING STATEMENT LAND SOUTH AND EAST OF ADASTRAL PARK On behalf of Carlyle Land Ltd and CEG Prepared by CODE Development Planners Ltd MARCH 2017 i Carlyle Land and CEG Land south and east of Adastral Park March 2017 ii Carlyle Land and CEG Land south and east of Adastral Park March 2017 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................. VII 1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................. 1 2 AIMS, OBJECTIVES AND BENEFITS OF THE PROPOSALS .......................................... 4 3 SITE CONTEXT .................................................................................................................. 7 4 RELEVANT PLANNING HISTORY..................................................................................... 8 5 PROPOSAL ........................................................................................................................ 8 6 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (EIA) ............................................................ 9 7 CONSULTATIONS ........................................................................................................... 10 8 RELEVANT PLANNING POLICY ..................................................................................... 11 9 GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE........................................................................................... -

Samena Trends Exclusively for Samena Telecommunications Council's Members Building Digital Economies

Volume 05 _ Issue 12 _ December 2014 SAMENA TRENDS EXCLUSIVELY FOR SAMENA TELECOMMUNICATIONS COUNCIL'S MEMBERS BUILDING DIGITAL ECONOMIES A SAMENA Telecommunications Council Newsletter Houlin Zhao Dr. Hamadoun I. Touré Secretary-General Former Secretary-General ITU ITU Building awareness of future trends and developments in the ICT sector www.samenacouncil.org SAMENA CONTENTS VOLUME _ 05 _ISSUE _ 12_DEC_2014 TRENDS The SAMENA TRENDS newsletter is REGIONAL & MEMBERS wholly owned and operated by The UPDATES SAMENA Telecommunications Council 13. Regional & Members News FZ, LLC (SAMENA). Information in the newsletter is not intended as professional 18. A journey of innovation at the heart services advice, and SAMENA Council disclaims any liability for use of specific of technology information or results thereof. Articles and information contained in this REGULATORY & POLICY publication are the copyright of SAMENA UPDATES Telecommunications Council, (unless 25. Beyond Internet Access otherwise noted, described or stated) and cannot be reproduced, copied or printed in any form without the express 27. Regulatory News written permission of the publisher. 33. A Snapshot of Regulatory Activities The SAMENA Council does not necessar- in SAMENA Region ily endorse, support, sanction, encour- age, verify or agree with the content, comments, opinions or statements made WHOLESALE UPDATES in The SAMENA TRENDS by any entity 53. Wholesale News or entities. Information, products and services offered, sold or placed in the TECHNOLOGY UPDATES newsletter by other than The SAMENA 58. Unscrambling Big Data Council belong to the respective entity EDITORIAL or entities and are not representative of The SAMENA Council. The SAMENA 03. 59. Technology News Council hereby expressly disclaims any and all warranties, expressed and im- 62. -

The Shift from Analogue to Digital - All IP Transformation

The shift from analogue to digital - all IP transformation Sodhi Dhillon BT Consumer 1 © British Telecommunications plc 2019 The transition to digital through our all IP transformation BT intends for all its customers to be using fully digital telephone services by December 2025. The first Consumer proposition will launch this year. The UK is not the first country transitioning to all IP. Other global communications companies (in Germany, Japan, Sweden and other countries) are ahead of us in the process of upgrading to digital telephone services. Special services that rely on our analogue PSTN network may be impacted by the move to all IP, and we’re fully committed in working with customers and industry to make this a seamless transition. We’ve been engaging with the industry for the last 18 months and are now collaborating even further with joint communication campaigns with many trade bodies and suppliers. 2 © British Telecommunications plc 2017 The roadmap to digital telephone services • May 2018: Openreach started WLR closure consultation. • July 2018: new test facility opened at BT’s R&D site. December 2025: All BT • November 2018: BT Consumer launched the SmartHub 2 customers are using digital which is compatible with Digital Voice. telephone services. 2018 2019 2023 2025 • 2019 – BT Consumer launches its Digital Voice • September – Openreach plans to stop sell products for residential customers. new PSTN / ISDN lines, so no new sales from this time. 3 © British Telecommunications plc 2017 How is the communications network will change • The telephone service is changing from analogue to digital and can be delivered over fibre and copper. -

BT to Honour Computer Pioneer Tommy Flowers, MBE

BT To Honour Computer Pioneer Tommy Flowers, MBE BT is marking the 70th anniversary of the creation of the world’s first programmable computer by unveiling a memorial sculpture of its inventor and launching a new award and scholarship in the field of Computer Science • In November 1943, Tommy Flowers, an electrical engineer working in the telecommunications department of the General Post Office (which became BT in 1984), designed and built the world’s first programmable computer • Flowers developed ‘Colossus’ at the Ministry of Defence’s code-breaking facility in Bletchley Park to counter the supposedly unbreakable Lorenz cipher used by the German High Command • After World War II, Flowers went on to direct ground-breaking research in the field of telecommunications, including the development of the first all- electronic telephone exchange • In December 2013, a memorial bust of Tommy Flowers created by the sculptor James Butler MBE will be unveiled at Adastral Park, BT’s global research and development headquarters at Martlesham, Suffolk • The Tommy Flowers’ Computing Science Scholarship in association with BT will offer academic mentoring, financial support and professional experience to students starting Year 12 in September 2013 • Two Tommy Flowers’ Awards for Commitment to Computing will also be launched by BT in September 2013 in order to celebrate the inspirational teaching of Computer Science at Key Stages 2 and 3 BT is celebrating the life and work of Tommy Flowers MBE, a telecoms pioneer and creator of the world’s first programmable computer, with a memorial sculpture and the launch of a scholarship and award in his name. -

Pension Scheme Liability

Latest revision of this document: https://library.prospect.org.uk/id/2013/00584 This revision: https://library.prospect.org.uk/id/2013/00584/2013-04-25 annual report 2012 union for professionals INDEX Introduction 1 Membership, recruitment and organisation 3 2 Managing the union 6 3 Rights at work 10 4 Benefits and services 14 5 Training and skills 16 6 Awards 20 7 Other organisations 21 8 Finance 24 Financial statement and accounts 28 Statement of responsibilities of the National Executive Committee 28 Report of the auditors 28 Statement to members 40 Donations and affiliations 41 Schedule of investments 42 Prospect Benevolent Fund 44 Education Trust 47 9 Executive, officers and committees 48 Prospect branches 53 Pay settlements 2012 57 Prospect structure 59 ii Prospect Annual Report 2012 INTRODUCTION The annual report provides the opportunity attacking poor policy and decisions through for Prospect to review the previous year and evidence derived from the experience and account to members for our actions and expertise of members and representatives. management of resources. In the past year we We have also backed members in protest, could have easily concluded that the strain including industrial action, where they on us, and the decline in membership, had wanted to take that course. We have also dulled Prospect’s vibrancy. We do have to played a full part in national protests through focus on the challenges we face, particularly the TUC. in organisation and recruitment, but this We have also litigated to defend our report tells the broader story of a union members’ individual and collective interests. -

BT 5G Innovation

5G Innovation Maria Cuevas June 2021 1 Applied Research and Adastral Park – home BT Labs and much more… Our world renowned innovation ecosystem and facilities mean that our research is open (152 companies on site), grounded in science (Universities) and purposeful (customer collaboration) Maximise our use of key specialisms at Universities in the UK and globally, leveraging Government investment in UK science BT Ireland IC 24x7 National Innovation Centre Link to location BT Security Openreach Operations Partners - Centre Academia Direct Innovation Cambridge University Co BT’s main security engagement UK Network University of Martlesham: Specialist Lab presence between OR and Suffolk, UEA, Largest UK ICT benefitting from Operation Cambridge and cluster with 141 Fundamentals Applied Centre Lancaster University Research Research Essex companies Specialist Lab Operational Optimisation Manchester Adastral Park Research HQ Birmingham University – Largest UK ICT Cluster Specialist Lab Long range radio 5G Lab, IoT Quantum Sensing Quantum Network Test Drone test High Potential Network Link propagation test Facility testbed / T&D facility Opportunity location facilities license Commercial- Rolled out at Birmingham grade quantum Equipment and Largest test and Adastral Park with Nearby RAF key distribution open space integration 11 companies Bentwaters University of Bristol link required facility in Europe testing Specialist Lab Cyber, Mobile, Optics, Quantum, Wireless, & AI Bristol London – UK’s 3rd largest ICT cluster Patenting team – Co-located -

BT Investor Relations Bulletin

BT Group Investor Relations Bulletin News and events during Q1 2021/22 1 July 2021 Contents Upcoming events ......................................................................................................................... 1 BT Group – BT Board and Executive Committee changes ........................................................ 1 BT Group – BT Board and Executive Committee share purchases ........................................... 1 BT Group – Environmental, Social, Governance ........................................................................ 2 BT Group – BT and the Communications Workers Union (CWU) agree a moratorium ........... 2 BT Group – BT concludes triennial pension valuation ................................................................ 2 BT Group – Altice acquires 12.1% stake in BT .............................................................................. 2 Government – Consultation to support the Telecommunications Infrastructure Act ............. 2 Regulation – Ofcom publishes its quarterly telecoms and pay TV complaints ....................... 2 Consumer – BT extends partnership with, and invests in, Enjoy Technology............................ 2 Consumer – BT confirms it is in discussions about the future of BT Sport ................................... 3 Consumer – English Premier League extends rights for existing holders................................... 3 Consumer – BT updates statement on Class Action claim from Mishcon de Reya ................ 3 Consumer – BT launches social tariff for broadband