The Florida Historical Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

En Vogue L at Oya C R O S S

- Left to Right: Tem inimus sequiae veriatem quam, estibus amet et aborerro offici de rest, quam, tendand uscienti ut FROM QUARTET TO TRIO, THE FUNKY DIVAS STILL SHOW (AND PROVE) THEY WERE BORN TO SING :EN VOGUE L AT OYA C R O S S APRIL/MAY 2017 EBONY.COM 83 lion YouTube views. But wait, there’s connection that goes into play when to learn each of more: The sultry songstresses climbed blending voices, one that Bennett came En Vogue members, from left, Rhona Bennett, the girls and re- the charts six times with singles “Hold equipped with, Ellis explains. Terry Ellis and Cindy Herron-Braggs spect the difer- On,” “My Lovin’ (Never Gonna Get “It’s being conscious of each other ences,” says El- It),” “Free Your Mind,” “Giving Him when we’re singing,” she says. “Where lis, the youngest THE SUPREMES.The Marvelettes. Something He Can Feel,” “Don’t Let is she placing her vibrato? What’s the of fve siblings. The Pointer Sisters. Between the 1960s Go,” and “Whatta Man” featuring tempo or how is she executing this song, “For me, that’s and the 1980s, the music scene was Salt-N-Pepa. this line or this word? I never thought freeing your dominated by timeless female groups. On top of their silky siren abilities, about it, but maybe that does come with mind. I think the But when it comes to girl group dynam- pop culture embraced the clingy red some seasoning and time. Rhona is a key is to under- ics, the 1990s are defned by En Vogue— dresses the vocally gifed women se- veteran as well, so she came in with that stand that you a foursome equipped with efortless duced viewers with in the music video information and awareness already. -

(Elwood Meredith) Beck, Jr. Spring 2011

E.M. (Elwood Meredith) Beck, Jr. Spring 2011 RANK/POSITION Professor Emeritus of Sociology Meigs Distinguished Teaching Professor Emeritus OFFICE Department of Sociology University of Georgia Athens, Georgia 30602-1611 Phone: 1.706.542.2421 FAX: 1.706.542.4320 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://uga.edu/soc/people/faculty/beck_em.php RESIDENCE 512 Ashbrook Court Athens, Georgia 30605-3986 Phone: 1.706.546.5857 MARITAL STATUS Married to Virginia H. Davis-Beck. EDUCATION 1968 B.A. (American History), University of Alabama, Senior Paper: “Effects of Industrialization on Political Behavior in Southern Cities: A Case Study of Birmingham, Alabama, 1900 to 1920.” 1969 M.A. (Sociology), University of Tennessee, Master’s Thesis: “Organizational Determinants of Social Conflict. The Development and Testing of a Model for the Public School.” 1972 Ph.D. (Sociology), University of Tennessee, Doctoral Thesis: “A Study of Rural Industrial Development and Occupational Mobility.” AREAS OF • Race Discrimination and Racial Violence • Poverty and Inequality INTEREST • Sociology of the American South • Quantitative Methodology and Statistics; Simultaneous Equations Models; Bayesian Estimation and Inference PROFESSIONAL • American Sociological Association • Southern Sociological Society MEMBERSHIPS • Southern Historical Association • International Sociological Association • International Association for the Study of Racism • Mid-South Sociological Association • Georgia Sociological Association Experience 1966 Research Intern, Oak Ridge Associated Universities. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:_December 13, 2006_ I, James Michael Rhyne______________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in: History It is entitled: Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Wayne K. Durrill_____________ _Christopher Phillips_________ _Wendy Kline__________________ _Linda Przybyszewski__________ Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences 2006 By James Michael Rhyne M.A., Western Carolina University, 1997 M-Div., Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1989 B.A., Wake Forest University, 1982 Committee Chair: Professor Wayne K. Durrill Abstract Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region By James Michael Rhyne In the late antebellum period, changing economic and social realities fostered conflicts among Kentuckians as tension built over a number of issues, especially the future of slavery. Local clashes matured into widespread, violent confrontations during the Civil War, as an ugly guerrilla war raged through much of the state. Additionally, African Americans engaged in a wartime contest over the meaning of freedom. Nowhere were these interconnected conflicts more clearly evidenced than in the Bluegrass Region. Though Kentucky had never seceded, the Freedmen’s Bureau established a branch in the Commonwealth after the war. -

For Indian River County Histories

Index for Indian River County Histories KEY CODES TO INDEXES OF INDIAN RIVER COUNTY HISTORIES Each code represents a book located on our shelf. For example: Akerman Joe A, Jr., M025 This means that the name Joe Akerman is located on page 25 in the book called Miley’s Memos. The catalog numbers are the dewey decimal numbers used in the Florida History Department of the Indian River County Main Library, Vero Beach, Florida. Code Title Author Catalog No. A A History of Indian River County: A Sense of Sydney Johnston 975.928 JOH Place C The Indian River County Cook Book 641.5 IND E The History of Education in Indian River Judy Voyles 975.928 His County F Florida’s Historic Indian River County Charlotte 975.928.LOC Lockwood H Florida’s Hibiscus City: Vero Beach J. Noble Richards 975.928 RIC I Indian River: Florida’s Treasure Coast Walter R. Hellier 975.928 Hel M Miley’s Memos Charles S. Miley 975.929 Mil N Mimeo News [1953-1962] 975.929 Mim P Pioneer Chit Chat W. C. Thompson & 975.928 Tho Henry C. Thompson S Stories of Early Life Along the Beautiful Indian Anna Pearl 975.928 Sto River Leonard Newman T Tales of Sebastian Sebastian River 975.928 Tal Area Historical Society V Old Fort Vinton in Indian River County Claude J. Rahn 975.928 Rah W More Tales of Sebastian Sebastian River 975.928 Tal Area Historical Society 1 Index for Indian River County Histories 1958 Theatre Guild Series Adam Eby Family, N46 The Curious Savage, H356 Adams Father's Been to Mars, H356 Adam G, I125 John Loves Mary, H356 Alto, M079, I108, H184, H257 1962 Theatre Guild -

PHR Local Website Update 4-25-08

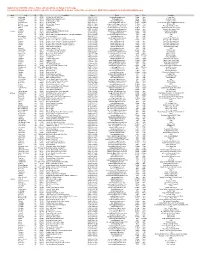

Updated as of 4/25/08 - Dates, Times and Locations are Subject to Change For more information or to confirm a specific local competition, please contact the Local Host or MLB PHR Headquarters at [email protected] State City ST Zip Local Host Phone Email Date Time Location Alaska Anchorage AK 99508 Mt View Boys & Girls Club (907) 297-5416 [email protected] 22-Apr 4pm Lions Park Anchorage AK 99516 Alaska Quakes Baseball Club (907) 344-2832 [email protected] 3-May Noon Kosinski Fields Cordova AK 99574 Cordova Little League (907) 424-3147 [email protected] 26-Apr 10am Volunteer Park Delta Junction AK 99737 Delta Baseball (907) 895-9878 [email protected] 6-May 4:30pm Delta Junction City Park HS Baseball Field Eielson AK 99702 Eielson Youth Program (907) 377-1069 [email protected] 17-May 11am Eielson AFB Elmendorf AFB AK 99506 3 SVS/SVYY (907) 868-4781 [email protected] 26-Apr 10am Elmendorf Air Force Base Nikiski AK 99635 NPRSA 907-776-8800x29 [email protected] 10-May 10am Nikiski North Star Elementary Seward AK 99664 Seward Parks & Rec (907) 224-4054 [email protected] 10-May 1pm Seward Little League Field Alabama Anniston AL 36201 Wellborn Baseball Softball for Youth (256) 283-0585 [email protected] 5-Apr 10am Wellborn Sportsplex Atmore AL 36052 Atmore Area YMCA (251) 368-9622 [email protected] 12-Apr 11am Atmore Area YMCA Atmore AL 36502 Atmore Babe Ruth Baseball/Atmore Cal Ripken Baseball (251) 368-4644 [email protected] TBD TBD TBD Birmingham AL 35211 AG Gaston -

Artist's Proposal

Gabbert Artist’s Proposal 14th Street Roundabout Page 434 of 1673 Gabbert Sarasota Roundabout 41&14th James Gabbert Sculptor Ladies and Gentlemen, Thank you for this opportunity. For your consideration I propose a work tentatively titled “Flame”. I believe it to be simple-yet- compelling, symbolic, and appropriate to this setting. Dimensions will be 20 feet high by 14.5 feet wide by 14.5 feet deep. It sits on a 3.5 feet high by 9 feet in diameter base. (not accurately dimensioned in the 3D graphics) The composition. The design has substance, and yet, there is practically no impediment to drivers’ visibility. After review of the design by a structural engineer the flame flicks may need to be pierced with openings to meet the 150 mph wind velocity requirement. I see no problem in adjusting the design to accommodate any change like this. Fire can represent our passions, zeal, creativity, and motivation. The “flame” can suggest the light held by the Statue of Liberty, the fire from Prometheus, the spirit of the city, and the hearth-fire of 612.207.8895 | jgsculpture.webs.com | [email protected] 14th Street Roundabout Page 435 of 1673 Gabbert Sarasota Roundabout 41&14th James Gabbert Sculptor home. It would be lit at night with a soft glow from within. A flame creates a sense of place because everyone is drawn to a fire. A flame sheds light and warmth. Reference my “Hopes and Dreams” in my work example to get a sense of what this would look like. The four circles suggest unity and wholeness, or, the circle of life, or, the earth/universe. -

Florida Historical Quarterly (ISSN 0015-4113) Is Published by the Florida Historical Society, University of South Florida, 4202 E

COVER Black Bahamian community of Coconut Grove, late nineteenth century. This is the entire black community in front of Ralph Munroe’s boathouse. Photograph courtesy Ralph Middleton Munroe Collection, Historical Association of Southern Florida, Miami, Florida. The Historical Volume LXX, Number 4 April 1992 The Florida Historical Quarterly (ISSN 0015-4113) is published by the Florida Historical Society, University of South Florida, 4202 E. Fowler Avenue, Tampa, FL 33620, and is printed by E. O. Painter Printing Co., DeLeon Springs, FL. Second-class postage paid at Tampa, FL, and at additional mailing office. POST- MASTER: Send address changes to the Florida Historical Society, P. O. Box 290197, Tampa, FL 33687. Copyright 1992 by the Florida Historical Society, Tampa, Florida. THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY Samuel Proctor, Editor Mark I. Greenberg, Editorial Assistant EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD David R. Colburn University of Florida Herbert J. Doherty University of Florida Michael V. Gannon University of Florida John K. Mahon University of Florida (Emeritus) Joe M. Richardson Florida State University Jerrell H. Shofner University of Central Florida Charlton W. Tebeau University of Miami (Emeritus) Correspondence concerning contributions, books for review, and all editorial matters should be addressed to the Editor, Florida Historical Quarterly, Box 14045, University Station, Gainesville, Florida 32604-2045. The Quarterly is interested in articles and documents pertaining to the history of Florida. Sources, style, footnote form, original- ity of material and interpretation, clarity of thought, and in- terest of readers are considered. All copy, including footnotes, should be double-spaced. Footnotes are to be numbered con- secutively in the text and assembled at the end of the article. -

„Wir Schauspielern Zu Musik“ Sein Kann

ich in der Frage, wie viel Haut man zeigt, sehr konservativ. SPIEGEL: Wie kommt es dann, dass Sie im neuen En-Vogue-Video zum Song „Riddle“ mit Abstand den kürzesten Rock tragen? Ellis: Ich bin selbst erschrocken, als der Sty- list damit ankam. Früher hätte ich mich ge- weigert, jetzt sagte ich nur: Gebt mir eine Strumpfhose, und ich ziehe ihn an. SPIEGEL: Inwiefern verpflichtet Sie der Bandname En Vogue, modisch immer auf der Höhe der Zeit zu sein? Ellis: Das gehört natürlich dazu. In dieser Saison gefällt mir am besten die Schlangen- Optik, die überall zu sehen ist. Und ich überlege, ob ich mir eine dieser modischen Geldbörsen kaufen soll, die aussehen wie Briefumschläge. Im Grunde bin ich aber ein Blue-Jeans-Mädchen. Am liebsten möchte ich immer in Jeans auftreten. Nur würden das unsere Fans nicht erlauben. SPIEGEL: Sie meinen, die würden Ihre Platten nicht kaufen, wenn Sie Hosen EASTWEST anhätten? „En Vogue“-Stars Jones, Herron, Ellis: „Je reifer du bist, desto sexier bist du“ Ellis: Wir haben einfach ein bestimmtes Image, das von Anfang an sehr durch Op- tik geprägt war. Wir haben damit angefan- POP gen – jetzt müssen wir die Erwartungen der Fans eben erfüllen … Jones: … was manchmal sehr anstrengend „Wir schauspielern zu Musik“ sein kann. Es dauert Stunden, bis wir so aussehen, wie man uns aus unseren Videos Die En-Vogue-Sängerinnen Terry Ellis und kennt. SPIEGEL: Make-up und perfektes Styling Maxine Jones über Girl Groups, nackte Haut auf der Bühne sind also genauso wichtig wie die Musik? und Rollenspiele im Popgeschäft Ellis: Wir spielen eine Rolle. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFO RM A TIO N TO U SER S This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI film s the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be fromany type of con^uter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependentquality upon o fthe the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and inqjroper alignment can adverse^ afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note wiD indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one e3q)osure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photogr^hs included inoriginal the manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for aiy photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI direct^ to order. UMJ A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313.'761-4700 800/521-0600 LAWLESSNESS AND THE NEW DEAL; CONGRESS AND ANTILYNCHING LEGISLATION, 1934-1938 DISSERTATION presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Robin Bernice Balthrope, A.B., J.D., M.A. -

Congressional Record-Sen

. .,.. - ---- ... ----- 1928 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE 711 Joy Street, Boston, Mass., recommending passage of the Newton the Senate, the unveiling of the Wright Brothers Monument bill, which provides for the creation of a child welfare exten at Kitty Hawk, N. C. sion service in the Children's Bureau ; to the Committee on The VICE PRESIDENT. Eighty-one Senators having an Education. swered to their names, a quorum is present. 8011. By Mr. YATES : Petition· of Le Seure Bros., jobbers and MESSAGE FROM THE HOUSFi-ENROLLED BILL SIGNED retailers of cigars and tobaccos, Danville, Ohio, protesting Senate bill 2751; to the Committee on Ways and Means. A message from the House of Representatives, by Mr. Halti 8012. Also, petition of H. M. Voorhis, of the law offices of gan, one of its clerks, announced that the Speaker had affixed to R. Maguire & Voorhis, of Orlando, Fla., urging passage of the his signature the enrolled bill (H. 13990) to authorize the Sears bill (H. R. 10Z70) ; to the Committee on the Judiciary. President to present the distinguished flying cross to Orville Wright, and to Wilbur Wright, deceased, and it was signed by 8013. Also, petition of W. T. Alden, of the law offices of Alden, the Vice President. Latham & Young, Chicago, Ill., urging passage of Senate bill 3623, amending section 204 of the transportation act of 1920 ; PETITIONS AND MEMOKIALS to the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. The VICE PRESIDENT laid before the Senate a petition of 8014. Also, petition of the legislative committee of the Rail sundry citizens of St. Petersburg, Fla., praying for the prompt way Mail Association, Illinois Branch, Chicago, urging passage ratification of the so-called Kellogg multilateral treaty for the of the following bills: The retirement bill (S. -

Table of Contents

RECONSIDERATIONS – Second Glances at Florida Legislative Events Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................................... I DEDICATION OF THE 2006 EDITION.........................................................................................................................2 ADMISSIONS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...........................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION TO THE 1991 EDITION: .................................................................................................................4 MEMORABLE YEARS IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES.........................................................................6 THE SPEAKERS................................................................................................................................................................8 USE OF HUMOR BY SPEAKERS ..........................................................................................................................................9 TABLE TURNED ON SPEAKER HABEN ...............................................................................................................................9 ART OF UNDERSTATED HUMOR......................................................................................................................................11 TUCKER AND GOVERNORSHIP.........................................................................................................................................11 -

An Obligation to Do One's Best by Dana Smessaert May 2020

An Obligation to do One’s Best by Dana Smessaert May 2020 Director of Thesis: Angela Wells Major Department: School of Art and Design An Obligation to do One's Best is an exploration of myth and reality at home in a small southern town. The artist is calling into question whose history we are referencing when it comes to art, economics, and culture. In these liminal landscapes, the viewer/spectator becomes a collaborator in the mythos of racism in the Southern narrative—the denial of not only its racist past but also the strides of the Civil Rights protests. The research explores the agency of history and cultural capital through a site-specific installation with images, video, sculpture, and sound. Creating a liminal landscape of the American South through physical and metaphysical readings of its trauma, history, and understanding the “...south as a noun that behaves like a verb.”1 The South is entwined with history, politics, economics, and racism, a link that can never be severed, this paper consorts with classic literature, history, cinema, demographics, and philosophy. The American South, the house, the name, and the family's history are complicated and seemingly transparent to those on the outside. However, the stories of those who live here still exist in the space between myth and reality. 1 Romine, Scott. The Real South: Southern Narrative in the Age of Cultural Reproduction. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2008. An Obligation to do One’s Best A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the School of Art and Design East