Decline and No Growth: Canada's Forgotten Urban Interior*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3. the Montreal Jewish Community and the Holocaust by Max Beer

Curr Psychol DOI 10.1007/s12144-007-9017-3 The Montreal Jewish Community and the Holocaust Max Beer # Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2007 Abstract In 1993 Hitler and the Nazi party came to power in Germany. At the same time, in Canada in general and in Montreal in particular, anti-Semitism was becoming more widespread. The Canadian Jewish Congress, as a result of the growing tension in Europe and the increase in anti-Semitism at home, was reborn in 1934 and became the authoritative voice of Canadian Jewry. During World War II the Nazis embarked on a campaign that resulted in the systematic extermination of millions of Jews. This article focuses on the Montreal Jewish community, its leadership, and their response to the fate of European Jewry. The study pays particular attention to the Canadian Jewish Congress which influenced the outlook of the community and its subsequent actions. As the war progressed, loyalty to Canada and support for the war effort became the overriding issues for the community and the leadership and concern for their European brethren faded into the background. Keywords Anti-Semitism . Holocaust . Montreal . Quebec . Canada . Bronfman . Uptowners . Downtowners . Congress . Caiserman The 1930s, with the devastating worldwide economic depression and the emergence of Nazism in Germany, set the stage for a war that would result in tens of millions of deaths and the mass extermination of Europe’s Jews. The decade marked a complete stoppage of Jewish immigration to Canada, an increase in anti-Semitism on the North American continent, and the revival of the Canadian Jewish Congress as the voice for the Canadian Jewish community. -

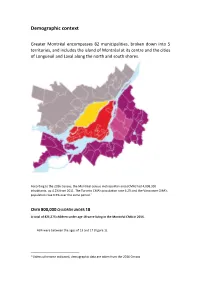

Demographic Context

Demographic context Greater Montréal encompasses 82 municipalities, broken down into 5 territories, and includes the island of Montréal at its centre and the cities of Longueuil and Laval along the north and south shores. According to the 2016 Census, the Montréal census metropolitan area (CMA) had 4,098,930 inhabitants, up 4.2% from 2011. The Toronto CMA’s population rose 6.2% and the Vancouver CMA’s population rose 6.5% over the same period.1 OVER 800,000 CHILDREN UNDER 18 A total of 821,275 children under age 18 were living in the Montréal CMA in 2016. — 46% were between the ages of 13 and 17 (Figure 1). 1 Unless otherwise indicated, demographic data are taken from the 2016 Census. Figure 1.8 Breakdown of the population under the age of 18 (by age) and in three age categories (%), Montréal census metropolitan area, 2016 Source: Statistics Canada (2017). 2016 Census, product no. 98-400-X2016001 in the Statistics Canada catalogue. The demographic weight of children under age 18 in Montréal is higher than in the rest of Quebec, in Vancouver and in Halifax, but is lower than in Calgary and Edmonton. While the number of children under 18 increased from 2001 to 2016, this group’s demographic weight relative to the overall population gradually decreased: from 21.6% in 2001, to 20.9% in 2006, to 20.3% in 2011, and then to 20% in 2016 (Figures 2 and 3). Figure 2 Demographic weight (%) of children under 18 within the overall population, by census metropolitan area, Canada, 2011 and 2016 22,2 22,0 21,8 21,4 21,1 20,8 20,7 20,4 20,3 20,2 20,2 25,0 20,0 19,0 18,7 18,1 18,0 20,0 15,0 10,0 5,0 0,0 2011 2016 Source: Statistics Canada (2017). -

Your Gateway to North American Markets

YOUR GATEWAY TO NORTH AMERICAN MARKETS Biopharmaceuticals Medical technologies Contract research organizations Incubators and accelerators Research centers Rental and construction opportunities GREATER MONTREAL A NETWORK OF INNOVATIVE BUSINESSES Private and public contract research organizations (CRO), medication manufacturers and developers (CMO and CDMO). A HOSPITAL NETWORK Over 30 hospitals, 2 of which are university “super hospitals”: the Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal and the McGill University Health Centre. A BUSINESS NETWORK BIOQuébec, Montréal In Vivo, Montréal International, Medtech Canada, etc. Biotech City supports the creation and growth of life sciences businesses by offering them an exceptional working environment. Rental spaces, laboratories, land, etc. Access to a network of R&D _ Assistance with funding applications; professionals and partners _ Financing programs available to _ A skilled workforce; SMEs; _ Collaboration between universities; _ Property tax credit; _ Events and networking (local _ International mobility support. ecosystem); _ Venture capital. A SEAMLESS VALUE CHAIN FROM DISCOVERY TO PRODUCTION The result of a partnership between the Ville de Laval and the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS), Biotech City is a business and scientific research centre focused on business development, innovation and business competitiveness. Strategically located near Montreal, Biotech City is also close to several airports. 110 5,500 4.5 1.2 businesses jobs billion in private millions of (multinationals, investments sq. m. dedicated SMEs, start-ups) since 2001 to life sciences and high-tech innovation VANCOUVER 5 h 30 min LAVAL MONTREAL TORONTO 1 h 10 min BOSTON 1 h 15 min NEW YORK 1 h 25 min SAN FRANCISCO 6 h 25 min RALEIGH-DURHAM 3 h 30 min QUEBEC BIOTECHNOLOGY INNOVATION CENTRE (QBIC) The QBIC has acted as an incubator for life sciences and health technologies companies for the past 25 years. -

Canada's Population 1

Canada’s Demographics Reading • Most standard textbooks on the geography of Canada have a population chapter Data Sources • Until September 2013 Census and StatsCan data was released to universities via E-STAT – Site discontinued • Data now available free on the web • Best to use the University’s on-line research guide Statscan Canada’s Population • Canada in 2016 had 36.3 million people • The birth rate is low, and falling – Except among aboriginal peoples • But Canada’s population still grew by 15% 2011-16 Canada’s Population • 2/3 of population growth now through immigration – From global and increasingly non-European sources – Immigrant and aboriginal fertility props up the birth rate • Canada had the fastest population growth in the G8 (5.9% in 2006-11, 15% 2011-16). Canada’s Population • Changes in Canada’s economy drive internal migration, and shift population growth – Nationally, growth connected to resource sector especially of energy resources – Decline of manufacturing jobs, locally, nationally • Population and employment shifts westwards to BC, Prairies. Population Size • Canada 1867: – 3.4 million people • Canada 2016: – 36.3 million people Population Distribution • Where do people live? • What kinds of settlements? Population Distribution • Population Density – People per unit of territory – Usually people/km2 • Canada 2011: – 33.5 Million people – 9.2 Million km2 of land area – 3.6 people/km2 Population Density Varies • Within Canada • 13.4 people/km2 in Ontario – Much higher in south, lower in north • 0.03 people/km2 in -

Industrial Outlook Q4 2020

JLL Research Report Canada | Q4 2020 Research Industrial Outlook Vacancy is once again reaching for historic lows as developers find creative ways to meet demand 2 Industrial Outlook | Canada | Q4 2020 Contents Key trends 3 State of the market 4 Local Markets Metro Vancouver 8 Calgary & Area 9 Greater Edmonton Area 10 Metro Winnipeg 11 Greater Toronto Area 12 Greater Ottawa Area 13 Greater Montréal Area 14 Greater Montréal Area (French) 15 Appendix 17 About JLL 19 Top industrial trends 1. 3 2. 3. After a slight Logistics Large scale multi- midyear uptick companies story industrial vacancy starts to overtake e- facilities make their trend downward commerce with Canadian debut as hitting 2.7% while over 2.7M s.f. of developers rents rise 7.2% in large lease activity scramble to meet 2020 in the fourth demand quarter 4 Industrial Outlook | Canada | Q4 2020 Canada key statistics Quarterly net YTD net Quarterly YTD Under Q4 2020 Total Total absorption absorption Completions Completions construction direct net Inventory (s.f.) vacancy availability (s.f.) (s.f.) (s.f.) (s.f.) (s.f.) rent 1,827,783,548 2.7% 3.8% 5,681,200 18,359,875 5,578,006 22,193,924 26,989,726 $9.92 After a slight uptick during the first wave of the pandemic vacancy and availability trend back down in the fourth quarter Strong user demand to close out 2020 has maintained historically tight market conditions 8.0% 7.0% 6.0% -40 bps Change in Availability rate in Q4 5.0% Vacancy Rate (%) 4.0% 3.0% 2.0% 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Availability Vacancy Source: JLL Research , CoStar, Altus Insite The Canadian Industrial market posted a vacancy rate of acquired almost 500,000 s.f. -

Aviation Investigation Report A93O0343

AVIATION OCCURRENCE REPORT LOSS OF CONTROL BEECH B58P BARON C-FKSB TORONTO ISLAND AIRPORT, ONTARIO 1.8 nm W 09 OCTOBER 1993 REPORT NUMBER A93O0343 MANDATE OF THE TSB The Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act provides the legal framework governing the TSB's activities. Basically, the TSB has a mandate to advance safety in the marine, pipeline, rail, and aviation modes of transportation by: ! conducting independent investigations and, if necessary, public inquiries into transportation occurrences in order to make findings as to their causes and contributing factors; ! reporting publicly on its investigations and public inquiries and on the related findings; ! identifying safety deficiencies as evidenced by transportation occurrences; ! making recommendations designed to eliminate or reduce any such safety deficiencies; and ! conducting special studies and special investigations on transportation safety matters. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. However, the Board must not refrain from fully reporting on the causes and contributing factors merely because fault or liability might be inferred from the Board's findings. INDEPENDENCE To enable the public to have confidence in the transportation accident investigation process, it is essential that the investigating agency be, and be seen to be, independent and free from any conflicts of interest when it investigates accidents, identifies safety deficiencies, and makes safety recommendations. Independence is a key feature of the TSB. The Board reports to Parliament through the President of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada and is separate from other government agencies and departments. Its independence enables it to be fully objective in arriving at its conclusions and recommendations. -

Metropolises Study Montreal

Metropolises A metropolis is a major urban centre where power and services are concentrated, and where issues abound. People in the surrounding region and even in the national territory as a whole are drawn to it. Today metropolises are increasingly powerful, which has repercussions for the entire planet. Québec Education Program, Secondary School Education, Cycle One, p. 276 Study Territory: Montréal Note: This is an archived study file and is no longer updated. Portrait of the territory A French-speaking metropolis in North America About half of the population of the province of Québec is concentrated in the urban agglomeration of Montréal (also known as the Greater Montréal area), Québec’s largest metropolis, which has a population of 3.6. million people. The new demerged city of Montréal accounts for 1.6 million of these people, almost the entire population of the Island of Montréal. Montréal is the second largest metropolis in Canada, after Toronto, which has a metropolitan area with a population of over 5 million. In Canada, only Vancouver, Ottawa-Gatineau, Calgary and Edmonton also have metropolitan areas of over 1 million people. Updated source: Stats Canada Population profile The suburbs farthest from the centre of Montréal are experiencing the fastest population growth. In fact, for the last 10 years, the population of the city of Montréal itself has only increased slightly, with immigration compensating for the low birth rate of 1.1 children per family. Montréal is consequently a very multicultural city, with immigrants making up 28% of its population. (This percentage drops to 18% for the entire urban agglomeration). -

Taxes in Canada’S Largest Metropolitan Areas?

Josef Filipowicz and Steven Globerman Who Bears the Burden of Property Taxes in Canada’s Largest Metropolitan Areas? 2019 • Fraser Institute Who Bears the Burden of Property Taxes in Canada’s Largest Metropolitan Areas? by Josef Filipowicz and Steven Globerman fraserinstitute.org Contents Executive Summary / i 1. Introduction / 1 2. What Are Property Taxes? / 3 3. The Causes and Consequences of Higher Tax Rates on Commercial and Industrial Properties / 4 4. Property Tax Rates and Ratios in Canada’s Five Largest Metropolitan Areas / 8 5. Conclusion / 18 Appendix Property Tax Rates by Metropolitan Region / 19 About the authors / 26 Acknowledgments / 26 About the Fraser Institute / 27 Publishing Information / 28 Supporting the Fraser Institute / 29 Purpose, Funding, and Independence / 29 Editorial Advisory Board / 30 fraserinstitute.org fraserinstitute.org Filipowicz and Globerman • Who Bears the Burden of Property Taxes in Canada? • i Executive Summary Property taxes are the primary source of revenue for local governments in Canada. The revenues raised are used to pay for a variety of public services including police, schools, fire protection, roads, and sewers. Owners of different classes of property, including residential, commercial and industrial, pay taxes. In principle, both considerations of efficiency and fairness suggest that the taxes paid by individual property owners should reflect the costs that they impose on municipal service providers. This is commonly referred to as the “user pay” principle. Therefore, to the extent that property tax rates differ across property classes, the differences should reflect commensurate differences in the relative costs that those asset classes impose on municipalities. This study compares property tax ratios for major residential and non-residential property classes in five of Canada’s largest metropolitan areas: Ontario’s Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area, Quebec’s Greater Montreal, British Columbia’s Lower Mainland, and Alberta’s Calgary and Edmonton regions. -

Annual Report 2019-2020 a Strategic

CONTENTS A STRATEGIC YEAR CLICKABLE AT ALL TIMES! FOR INCREASING OUR SOCIAL IMPACT MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR BOARD OF DIRECTORS ANNUAL REPORT AND THE CENTRE’S TEAM STRATEGIC PLAN 2019-2020 SPECIALIZED ADDICTION HELPLINES APRIL 1ST, 2019 TO MARCH 31ST, 2020 The Centre’s Foundation Financial Statements INFORMATION AND REFERRAL CENTRE TELEPHONE WEB SITES GRAPHIC DESIGN: MUSTANG GRAPHIX OF GREATER MONTRÉAL 514 527-1375 INFO-REFERENCE.QC.CA WRITING: LUCIE KECHICHIAN 3155 RUE HOCHELAGA, BUREAU 101 211QC.CA PROOF READING: MICHAËL MAGNY MONTRÉAL (QUÉBEC) H1W 1G4 E-MAIL DROGUE-AIDEREFERENCE.QC.CA TRANSLATION: MARIA RIGAS [email protected] AIDEJEU.CA REGISTERED CHARITY NUMBER N° 10689 5840 RR001 A MESSAGE FROM THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS PRESIDENT ANNUAL REPORT 2019 APRIL 1ST, 2019 TO MARCH 31ST, 2020 20 Therefore, the Board members and I adopted the innovative MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT EXCITING GROWTH and ambitious five-year Strategic Plan which ended with the implementation of 211 in all of Greater Montréal in January MESSAGE FROM The time has come for me to give up my seat as President THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 2018. A new path for the future opened up for the Centre of the Information and Referral Centre of Greater Montréal's who is becoming more and more a key player in social BOARD OF DIRECTORS Board of Directors, in accordance with the Centre’s General development. It was therefore with pride that I congratulated AND THE CENTRE’S TEAM Regulations. I have sat on the Board as President for over our Executive Director in February for receiving the award a decade, since April 2008, to be exact, and it has been an STRATEGIC PLAN of Leadersphip de Centraide du Grand Montréal for her honour for me to stand by the Centre during that period of determination in first rallying her team and then municipal SPECIALIZED ADDICTION significant changes. -

Year End 2020 Results Conference Call

Year End 2020 Results Conference Call TSX:CAR.UN February 25, 2021 Disclaimer Today’s session and our answers to questions contain statements that constitute forward-looking statements about expected future events and financial and operating results of CAPREIT. These statements represent CAPREIT’s intentions, plans, expectations and beliefs as of the date hereof and are subject to certain risks and uncertainties. These statements are based on certain factors and assumptions regarding expected growth, results of operations, performance and business uncertainties are more fully described in CAPREIT’s regulatory filings, including our Annual Information Form and prospects and opportunities. Although such forward-looking statements are based upon assumptions that management believes are reasonable, there can be no assurance that actual results will be consistent with these forward-looking statements and actual results in future periods may differ materially from those expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. These risks and Managements’ Discussion and Analysis of the Results of Operations and Financial Condition, all of which can be obtained on SEDAR at www.sedar.com. Investors should not place undue reliance on any such forward-looking statements. Subject to applicable law, CAPREIT does not undertake any obligation to update or revise any forward-looking information. Non-IFRS Financial Measures CAPREIT prepares and releases unaudited condensed consolidated interim financial statements and audited consolidated annual financial statements in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”). In the MD&A, and in earnings releases and investor conference calls, as a complement to results provided in accordance with IFRS, CAPREIT also discloses and discusses certain financial measures not recognized under IFRS which do not have standard meanings prescribed by IFRS. -

Greater Montréal: So Many Reasons to Invest

Greater Montréal: So Many Reasons to Invest Old Port, Grande-Roue and downtown Montréal © Loïc Romer The world's best economic promotion agency at your service 2 Content 01 02 03 04 Montréal: A Strong and A World Leader in High A Deep and Growing Pool Attractive Operating Growing Metropolis, Value-Added Sectors of Highly Qualified Talent Costs and Incentives Strategically Located p.7 p.10 p.13 p.3 05 06 An Exceptional Quality Montréal International’s of Life Personalized, Free and p.16 Confidential Services p.20 3 A strong and growing metropolis, strategically located in North America Population ▪ 4.3 million residents ▪ 23% of population are foreign-born (34% for the city of Montréal) Economy MONTRÉAL ▪ Best economic growth in Canada in 2018 TORONTO and 2019 VANCOUVER CHICAGO LONDRON ▪ Unemployment rate (2020): 5.6% ▪ $2.6 billion in foreign direct investment BOSTON PARIS in 2019 supported by Montréal International NEW YORK WASHINGTON Location ▪ 82 municipalities, 1 metropolitan area ▪ A 90-minute flight to Boston and New York City ▪ Less than a one-hour drive to the U.S. border LOS ANGELES Source: Conference Board of Canada, 2020; Statistics Canada, 2020; Montréal 4 International Analysis. A booming economy built on a strong foundation Greater Montréal is a A Aa2 credit rating for Access to a clean (99%), champion of economic Québec, with a stable renewable, stable and growth in Canada in 2018 outlook affordable electricity and 2019 Moody's, 2019 Lowest rates among the 20 largest metropolitan areas in Canada and the U.S. Québec has a well- Home to the Caisse de balanced budgetary policy dépôt et placement du Advantageous and stable Québec, one of the largest incentives institutional fund managers Research and development, in North America multimedia production, Among the largest pension e-business development, fund managers worldwide video and film production, and international financial centres, etc. -

2018 Report Supplementary Data

2018 FIRST CAPITAL REALTY INC. Corporate Responsibility and Sustainability (CRS) Report Supplementary Data Click this icon in the top page menu to return to the Table of Contents. TABLE OF CONTENTS COMPANY PROFILE ................................................................................................................ 1 EMPLOYEES .................................................................................................................................. 3 ENVIRONMENT .......................................................................................................................... 10 GREEN BUILDINGS ................................................................................................................. 15 DATA ASSUMPTIONS AND METHODOLOGIES ............................................ 17 Artwork: Carbon Copy Artist: Caitlind Brown & Wayne Garrett The Brewery District, Edmonton COMPANY PROFILE EMPLOYEES ENVIRONMENT GREEN BUILDINGS DATA ASSUMPTIONS AND METHODOLOGIES COMPANY PROFILE FPO/SHARE NAV/SHARE POPULATION HIGH-QUALITY PORTFOLIO OF URBAN ASSETS ($) ($) (100,000s) +22.2% since Jan 1, 2016 +23.8% since Jan 1, 2016 Within 5 Km radius Greater Toronto Area 1.21 22.59 250 21.85 1.16 Greater Montreal Area 215 1.11 207 6% Greater Calgary Area 8% 19.53 186 Greater Vancouver Area 9% 40% Greater Edmonton Area 11% Other Greater Ottawa Area 12% 16 17 18 16 17 18 15 16 17 18 14% All data as of December 31 IFRS Fair Values as at December 31, 2018 NORTH AMERICAN LEADER IN POPULATION DENSITY $120K 250K $113K $100K 153K US