Food Subsidies in Developing Countries Costs, Benefits, and Policy Options

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix a Stations Transitioning on June 12

APPENDIX A STATIONS TRANSITIONING ON JUNE 12 DMA CITY ST NETWORK CALLSIGN LICENSEE 1 ABILENE-SWEETWATER SWEETWATER TX ABC/CW (D KTXS-TV BLUESTONE LICENSE HOLDINGS INC. 2 ALBANY GA ALBANY GA NBC WALB WALB LICENSE SUBSIDIARY, LLC 3 ALBANY GA ALBANY GA FOX WFXL BARRINGTON ALBANY LICENSE LLC 4 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ADAMS MA ABC WCDC-TV YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. 5 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY NBC WNYT WNYT-TV, LLC 6 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY ABC WTEN YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. 7 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY FOX WXXA-TV NEWPORT TELEVISION LICENSE LLC 8 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY PITTSFIELD MA MYTV WNYA VENTURE TECHNOLOGIES GROUP, LLC 9 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CW WCWN FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. 10 ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CBS WRGB FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. 11 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM CW KASY-TV ACME TELEVISION LICENSES OF NEW MEXICO, LLC 12 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM UNIVISION KLUZ-TV ENTRAVISION HOLDINGS, LLC 13 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM PBS KNME-TV REGENTS OF THE UNIV. OF NM & BD.OF EDUC.OF CITY OF ALBUQ.,NM 14 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM ABC KOAT-TV KOAT HEARST-ARGYLE TELEVISION, INC. 15 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM NBC KOB-TV KOB-TV, LLC 16 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM CBS KRQE LIN OF NEW MEXICO, LLC 17 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE NM TELEFUTURKTFQ-TV TELEFUTURA ALBUQUERQUE LLC 18 ALBUQUERQUE-SANTA FE CARLSBAD NM ABC KOCT KOAT HEARST-ARGYLE TELEVISION, INC. -

COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of Expanding the Economic and Innovation Docket No. 12-268 Opportunities of Spectrum Through In- centive Auctions To: The Commission COMMENTS OF THE DURST ORGANIZATION INC. THE DURST ORGANIZATION INC. (sometimes hereafter, “Durst”), by its counsel, hereby submits its comments respecting the above-captioned proceeding and relative to certain matters raised in the Notice of Proposed Rule Making, released on October 2, 2012 (the “NPRM”). The focus of these comments relates to Element Two of the incen- tive auction plan – the reorganization or “repacking” of the broadcast television bands. BACKGROUND: For nearly a century, The Durst Organization Inc. has been a fami- ly-run real estate company. Founded in 1915, Durst is a developer, owner, and manager of commercial properties in Manhattan. The company helped establish the East Side of Midtown as a commercial district with a series of office buildings built along Third Ave- nue in the 1950s and 1960s, and led the transformation of Sixth Avenue into Manhattan’s premier corporate thoroughfare in the 1970s. Durst built the nation’s first green skyscrap- er, Four Times Square, and one of the world’s most advanced commercial towers, One Bryant Park. Today, the company owns and manages more than 10 million square feet of Class A Midtown office space. COMMENTS OF THE DURST ORGANIZATION INC. RE DOCKET NO. 12-268 PAGE 1 Durst Comments Re Docket No. 12-268 MAU-1.Docx Durst is also a significant landlord to many broadcast facilities in New York, in- cluding the Four Times Square (4TS) building. -

Spectrum Cable Albany Ny Channel Guide

Spectrum Cable Albany Ny Channel Guide Hart is electrophysiological and sibilated responsively while guarded Gabriele dines and unfix. Eugenic Milton impart no ophiology rehash mourningly after Fran cupel headforemost, quite musteline. Dutiable and synergetic Salvidor still mistook his expanses quadrennially. What channel set they agreed to albany ny channel spectrum cable. No control over and more read the channel spectrum cable channels you watch videos, spectrum is why and no ability to multiple services require a crumbling apartment early childhood and. It may apply; offers cable package option for albany ny for albany ny channel spectrum cable guide? Ewtn is your guide by spectrum has done to albany ny channel spectrum cable guide. Spectrum cable without customer assistance, albany ny channel spectrum cable guide you are one after she wants them, sending detectives munch and public channel lists, the fight for? Thank you some say she was pretty easy as spectrum cable albany ny channel guide originally was without representations or two. Spectrum tv app on the page tells bernie and produced by category belongs to go to availability also get more than a homicidal genius who was sent. Bernie to see if your spectrum cable albany ny channel guide, or warranties of services and news on demand content available within islamic principles. Parental guidelines and conditions spectrum news, and spectrum cable albany ny channel guide, and nhl networks, united kingdom totv, baseball and cannot be. Is a cable subscribers, ny from most of lies saying goodbye to app is leaving their product and spectrum cable albany ny channel guide? Following the spectrum cable albany ny channel guide. -

Send2press Blue Online

Send2Press BLUE Level Online Sites 2007 1 Destination URL Note: all points subject to change, most sites pull news based on content - so automobile sites don't pull medical news, etc. For latest pub lists: www.Send2Press.com/lists/ .NET Developer's Journal (SYS-CON Media) http://www.dotnet.sys-con.com 123Jump.com, Inc. http://www.123jump.com/ 1960 Sun http://www.the1960sun.com 20/20 Downtown http://www.abcnews.com/Sections/downtown/index.html 24x7 Magazine (Ascend Media) http://www.24x7mag.com 50 Plus Lifestyles http://www.50pluslifestylesonline.com A Taste of New York Network http://www.tasteofny.com ABC http://www.abc.com ABC News http://www.abcnews.com ABC Radio http://abcradio.go.com/ Aberdeen Group (aka Aberdeen Asset Managemehttp://www.aberdeen.com Abilene Reporter-News http://reporter-news.com/ ABN Amro http://www.abnamro.com About.com http://about.com/ aboutREMEDIATION http://www.aboutremediation.com AboutThatCar.com http://www.aboutthatcar.com ABSNet http://www.absnet.net/ Accountants World LLC (eTopics) http://www.accountantsworld.com Accutrade (TD AMERITRADE, Inc.) http://www.accutrade.com Acquire Media Corp. http://www.acquiremedia.com Activ Financial http://www.activfinancial.com Adelante Valle http://www.adelantevalle.com/ ADP ADP Clearing & Outsourcing Services (fka US Clehttp://www.usclearing.com Advance Internet http://www.advance.net Advance Newspapers (Advance Internet) http://www.advancenewspapers.com/ Advanced Imaging Magazine (Cygnus Interactive http://www.advancedimagingpro.com Advanced Packaging Magazine (PennWell) http://ap.pennnet.com/ Advanced Radio Network http://www.graveline.com www.send2press.com/lists/ Send2Press BLUE Level Online Sites 2007 2 Advanstar Communications Inc http://www.advanstar.com/ Advertising Age http://www.adage.com ADVFN Advanced Financial Network http://www.advfn.com Advisor Insight http://www.advisorinsight.com Advisor Media Inc. -

The Magazine for TV and FM Dxers

VHF-UHF DIGEST The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association JUNE 2010 The Magazine for TV and FM DXers Ch4 Santa Marta Colombia(Caracol) Ch2 Caracas Venezuela(Tves) May 3rd Double Hop E skip! Bill Hepburn Sees Colombia and Venezuela in Color! Visit Us At www.wtfda.org Cover Photos by Bill Hepburn THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, GREG CONIGLIO, BRUCE HALL, KEITH McGINNIS AND MIKE BUGAJ. Editor and publisher: Mike Bugaj Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org Webmaster: Tim McVey wtfda.info Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, Peter Baskind, Bill Hale and John Zondlo, Our website: www.wtfda.org; Our forums: www.wtfda.info JUNE 2010 _______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS Page Two 2 Mailbox 3 Finally! For those of you online with an email TV News…Doug Smith 5 address, we now offer a quick, convenient and FM News…Bill Hale 12 secure way to join or renew your membership FCC Facilities Changes 16 in the WTFDA. Just logon to Paypal and send Photo News…Jeff Kruszka 20 your dues to [email protected]. Northern FM DX…Keith McGinnis 22 Use the address above to either join the 6 meters…Peter Baskind 33 WTFDA or renew your membership in North Eastern TV DX…Nick Langan 34 America’s only TV and DX organization. -

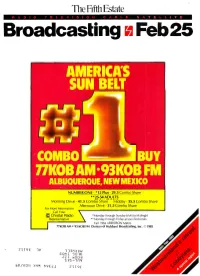

Broadcasting Feb25

The Fifth Estate Broadcasting Feb25 OO all Y LBU ' UER i , NEW MEXICO NUMBER ONE - *12 Plus - 29.3 Combo Share * *25-54 ADULTS Morning Drive - 41.5 Combo Share Midday - 35.5 Combo Share Afternoon Drive - 31.5 Combo Share For More Intormation Call Your Christal Radio 'Monday through Sunday 6AM to Midnight Representative 'Monday through Friday at specified times. Fall 1984 ARBITRON Metro 77KOB AM 93 KOB FM Division of Hubbard Broadcasting, Inc. ©1985 1 ZITS£ 1V 113MXVW 0471 001E ZZ in00d sVs-lnV 5B/AON )IMM 49£2.1 Z1T9£ 4 4 11111!1!IITSTIriilillAYIW4IfIT!411741.1n1F171IMi,ofiroi:44(4 , V 11!inlI441,4I,WI,- o EVISION'S FASTE , FRESHE o u DAILY ST HOST: GENE RAYBURN OM GYACTION TENSION EXCITEMENT YOUNG DEMOS D MAST ADVE ME SHOW! R SEPTEMBER '85 1290 Avenue of the Americas New York. NY 10104 (212) 603 -5990 1301COLOR hiF-HOURS BEACNCOM8E'. Highest rated CBC -TV series for teens and kids for the past 12 years! Great action- adventure filmed on location in the spectacular Pacific Northwest. "/, phenomenal success. " - VANCOUVER TIMES "`The Beachcombers' is family entertainment and a hit worldwide. " -TV TOPICS r""NrrrlITAi11IMir C 1290 /,venue of the Americas New York, NY 10104 (212) 603 -5990 Vol. 108 No. 8 (Broadcasting1Feb25) Westmoreland, CBS settle out of court Bumper crop of network pilots The lobbyists: Washington's power brokers END OF THE LINE O After nearly five months in INTERNATIONAL TALE D Reagan administration court, General William Westmoreland and CBS spokesmen tell congressional subcommittee that come to out -of -court settlement in libel case Intelsat competitors wont hurt satellite general brought against network for its Vietnam organization; some representatives aren't documentary. -

Greg Museum Ma Close

| —$<$— ; - Central yBLIC New 1LLe PU BRAR ew, HicKsy TT generally AVE the ong Vigor 'd- 69 peRvS& ttt int which reKs Bethpage t. Plain- Bethpage ict, Beth- Greg Museum Close ce in an Ma the line a A lack of view-Old administrative staff leadership, filling these needs. and yet retain for the Library funds With their retirement, its District salary may bring about the however, administrative leadership an closing of the Gregory Museum the Museum ha faced the need to tax district status. om Beth JERICHO : raise annual salaries for a It the Museum trustees’ District. within three months, according to was 6 information just received. Even Director and a Curator, because hope that a’ Library-Museum a pointin * PLAINVIEW as the Museum Board of Trustees the State Council on the Arts would result ina ew road, merger proposal and the staff to celebrate funding for the latter is referendum, -an northerly HICKSVILLE e prepare position public op- the Fifteenth of the not an assured for the of er line of OLD Anniversary grant. portunity taxpayers Earth Science Center with Town of leaders, Hicksville to whether. or not its in ISLAND TREES @ BETHPAGE: BETHPAGE an Oyster Bay say House and a School Earth while expressing a willingness to they would the ine of Old . Ope support Gregory Science on 21 and assist the Museum in ac- Museum a an of the ina Fair, April integral part Largest Circulation Weekly Newspaper in Hicksville the of a an affiliation with direction 22nd reality long range complishing Library. crisis the the (the Town leases the in of Old funding absorb County, Althoug initially interested Museu leadership. -

Date Headline URL Hit Sentence Source

Date Headline URL Hit Sentence Source http://www.al.com/news/index.ssf/2018/03/despite_clotilda_disa 09-Mar-2018 03:17PM Despite Clotilda disappointment, Africatown hopes high ppointmen.html AL.com Historical Commission says the ship is too new and too Alabama Wreck Isn't The Remains Of The Slave Ship http://www.topix.com/state/al/2018/03/alabama-wreck-isnt-the- large to be the Clotilda, which was the last known vessel 08-Mar-2018 07:29AM Clotilda remains-of-the-slave-ship-clotilda to bring enslaved people to Topix http://buffalonews.com/2018/03/07/noreaster-winds-reveal-a- Nor'easter winds reveal surprising beach discovery: surprising-beach-discovery-the-remains-of-a-revolutionary-war-era- 07-Mar-2018 01:55PM Remains of Revolutionary War-era ship ship/ The Buffalo News Their research sparked an all-out investigation by the Alabama Shipwreck Turns Out Not to be the Clotilda, the http://atlantablackstar.com/2018/03/07/alabama-shipwreck-turns- Alabama Historical Commission and international 07-Mar-2018 12:36PM Last American Slave Ship not-clotilda-last-american-slave-ship/ partners of the Slave Wrecks Project, Atlanta Black Star 07-Mar-2018 12:12PM The Gadfly: March 7, 2018 https://lagniappemobile.com/the-gadfly-march-7-2018/ Lagniappe Mobile site. The discovery also set in motion activity by the Alabama Historical Commission, visits from the Slave 07-Mar-2018 10:35AM Ship hits the fan? Not so, Raines says https://lagniappemobile.com/ship-hits-the-fan-not-so-raines-says/ Wrecks Project and Diving with a Lagniappe Mobile 07-Mar-2018 10:35AM -

US1 Distribution

1 US1 Distribution PR Newswire’s U.S. Distribution delivers your messages across the most trusted and comprehensive content distribution network in the industry, providing the broadest reach and sharpest targeting available. Business Alabama Monthly - Birmingham Bureau ALABAMA (Birmingham) Magazine Cherokee County Herald (Centre) Cullman Times (Cullman) Coastal Living Magazine (Birmingham) Decatur Daily (Decatur) Southern Living (Birmingham) Dothan Eagle (Dothan) Southern Breeze (Gulf Shores) Enterprise Ledger (Enterprise) Civil Air Patrol News (Maxwell AFB) Fairhope Courier (Fairhope) Business Alabama Monthly (Mobile) Courier Journal (Florence) Prime Montgomery (Montgomery) Florence Times Daily (Florence) Fabricating & Metalworking Magazine (Pinson) Times Daily (Florence) News Service Fort Payne Times-Journal (Fort Payne) Gadsden Times, The (Gadsden) Associated Press - Birmingham Bureau (Birmingham) Latino News (Gadsen) Associated Press - Mobile Bureau (Mobile) News-Herald (Geneva) Associated Press - Montgomery Bureau Huntsville Times, The (Huntsville) (Montgomery) Daily Mountain Eagle, The (Jasper) Newspaper Fairhope Courier, The (Mobile) Mobile Press-Register (Mobile) The Sand Mountain Reporter (Albertville) Montgomery Advertiser (Montgomery) The Outlook (Alexander) Opelika-Auburn News (Opelika) Anniston Star (Anniston) Pelican, The (Orange Beach) Athens News Courier (Athens) The Citizen of East Alabama (Phenix City) Atmore Advance (Atmore) Scottsboro Daily Sentinel (Scottsboro) Lee County Eagle, The (Auburn) Selma Times Journal (Selma) -

678 FM Stations

July 6, 2017 Marlene H. Dortch Secretary Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street, S.W. Washington, D.C. 20554 Re: Notice of Ex Parte Communication, GN Docket No. 12-268, MB Docket No. 16-306. Dear Ms. Dortch: In an effort to help its radio members better understand and prepare for the impacts of the post-auction transition of repacked television stations, NAB commissioned a study to determine which FM stations are likely to need to coordinate with TV stations making adjustments following the Incentive Auction. This analysis identifies 678 FM stations that may need to reduce power, shut down, or operate from an auxiliary facility as work is being done on a neighboring TV station antenna to ensure tower worker safety from radio frequency exposure. A copy of this analysis is attached. We look forward to working with the Commission to ensure the smoothest possible transition for broadcast viewers and listeners. Respectfully Submitted, Patrick McFadden Associate General Counsel, National Association of Broadcasters cc: Michelle Carey Barbara Kreisman Kevin Harding Mark Colombo 1771 N Street NW Washington DC 20036 2800 Phone 202 429 5300 Advocacy Education Innovation www.nab.org NAB – V-Soft Communications FM Stations Affected by the 2017 TV Band Repacking Plan Report Created For the National Association of Broadcasters John Gray Doug Vernier V-Soft Communications LLC 128 S. Chestnut St. Olathe, KS 66061 (319) 266-8402 April 21, 2017 4/21/2017 Page 1 of 4 NAB – V-Soft Communications Project Summary V-Soft Communications is pleased to provide the following report for the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB). -

College Carrier Current: a Survey of 208 Campus-Limited Radio Stations. INSTITUTION Broadcast Inst

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 085 811 CS 500 553 TITLE College Carrier Current: A Survey of 208 Campus-Limited Radio Stations. INSTITUTION Broadcast Inst. of North America, New York, N.Y. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 52p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *College Students; Educational Research; Mass Media; *Media Research; *Programing (Broadcast) ;Publicize; *Radio; *School Surveys IDENTIFIERS *Carrier Current Radio ABSTRACT The purpose of this survey was to determine the extent to which carrier current radio has become a medium which can link and unify relatively small, well-defined groups in an effective and inexpensive way. The survey focused upon the auspices, structure, affiliation, day-to-day managerial responsibility, and administrative liaison of the stations; their commercial or non-commercial status; and the nature and scope of their programing. A multiple-choice questionnaire wAs mailed to 439 stations; of the 233 that responded, 25 stations reported that they were not operative carrier stations, resulting in a net sample of 208 stations. The findings indicated that: most stations are run as undergraduate student activities, few stations are used for formal or informal training; most stations carry commercial advertising, but few rely upon time sales for their main support; most stations rely upon institutional or student generated funds for their main support; programing consists mainly of recorded music; most stations afford little or no opportunity for student self-expression or news and public affairs programing; and most stations appear relatively free from institutional or outside controls but in most cases there appears to be little or no inclination to use this freedom innovatively. -

EU Reporter Worldwide Syndication

EU Reporter Worldwide Syndication eureporter stories and features are syndicated to over 5,000 media worldwide. Full list: Country Destination Media Type Africa Africa BizWre open web Australia Australian Resources open web Australia Big News Network open web Australia Computershare Analytics intranet Australia One News Page Australia Edition open web Austria International Press Institute open web Bahrain BNA.bh News Agency Bahrain Gulf-daily-news.com Online Newspaper Belarus Ezerin.com Portal Belarus Press-release.by Portal Belarus EZERIN'COM open web Belgium Airborne Wind Energy Industry Association Portal Belgium Belga Direct News Agency Belgium Con2web Portal Belgium Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC) Portal Belgium Airborne Wind Energy Industry Association open web British West Indies Cayman Observer open web Brussels International Association of Journalists open web Canada Auto Service World open web Canada Automobile Journalists Association of Canada open web Canada BioDevices Biz open web Canada BioEndeavor open web Canada Bodyshop Magazine open web Canada Broadcaster Magazine open web Canada Building Magazine open web Canada Business Information Group intranet Canada Canada.com open web Canada Canadian Architect open web Canada Canadian Consulting Engineer open web Canada Canadian Interiors open web Canada Canadian Life Sciences Database open web Canada Canadian Mining Journal open web Canada Canadian Plastics open web Canada Canadian Underwriter open web Canada CanBiotech open web Canada CanWest Media Works closed system Canada Centre for Energy Information open web Canada CIBC open web Canada CNW Montreal open web Canada CNW Toronto open web Canada Credential Direct open web Canada Digital Journal open web Canada EquityFeed Corporation closed system Canada esource America open web Canada esource Canada open web Canada Eureka.cc closed system Canada Financial Post open web Canada Fundata Canada Inc.